Rethinking Anti-SLAPP Laws in the Age of the Internet Andrew L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best of 2014 Listener Poll Nominees

Nominees For 2014’s Best Albums From NPR Music’s All Songs Considered Artist Album ¡Aparato! ¡Aparato! The 2 Bears The Night is Young 50 Cent Animal Ambition A Sunny Day in Glasgow Sea When Absent A Winged Victory For The Sullen ATOMOS Ab-Soul These Days... Abdulla Rashim Unanimity Actress Ghettoville Adia Victoria Stuck in the South Adult Jazz Gist Is Afghan Whigs Do To The Beast Afternoons Say Yes Against Me! Transgender Dysphoria Blues Agalloch The Serpent & The Sphere Ages and Ages Divisionary Ai Aso Lone Alcest Shelter Alejandra Ribera La Boca Alice Boman EP II Allah-Las Worship The Sun Alt-J This is All Yours Alvvays Alvvays Amason Duvan EP Amen Dunes Love Ana Tijoux Vengo Andrew Bird Things Are Really Great Here, Sort Of... Andrew Jackson Jihad Christmas Island Andy Stott Faith In Strangers Angaleena Presley American Middle Class Angel Olsen Burn Your Fire For No Witness Animal Magic Tricks Sex Acts Annie Lennox Nostalgia Anonymous 4 David Lang: love fail Anthony D'Amato The Shipwreck From The Shore Antlers, The Familiars The Apache Relay The Apache Relay Aphex Twin Syro Arca Xen Archie Bronson Outfit Wild Crush Architecture In Helsinki NOW + 4EVA Ariel Pink Pom Pom Arturo O’Farrill & the Afro Latin Orchestra The Offense of the Drum Ásgeir In The Silence Ashanti BraveHeart August Alsina Testimony Augustin Hadelich Sibelius, Adès: Violin Concertos The Autumn Defense Fifth Avey Tare Enter The Slasher House Azealia Banks Broke With Expensive Taste Band Of Skulls Himalayan Banks Goddess Barbra Streisand Partners Basement Jaxx Junto Battle Trance Palace Of Wind Beach Slang Cheap Thrills on a Dead End Street Bebel Gilberto Tudo Beck Morning Phase Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn Bellows Blue Breath Ben Frost A U R O R A Benjamin Booker Benjamin Booker Big K.R.I.T. -

Mary Ellen Casey’

Roots Report: Don’t Let These Shows Pass You By Okee dokee folks … As I mentioned last month the summer shows are plenty. I have managed to get to quite a few so far and have many more to attend. One commonality I have noticed among the performers is that a lot of these folks are getting old, some very old. I guess I am, too. With age comes wisdom … or just the AARP? Shawn Colvin was the first of the bunch of concerts I went to last month. Colvin played the Narrows in Fall River, and she made several jokes alluding to her age. She is just 58 years old. In spite of her mocking her own diminished capacities of memory and eyesight, she put on a great show. Nimfest in Newport presented Susan Cowsill. She is the youngest member of the Cowsills and checks in at age 54, just a year older than I am. She still has the youthful look she had as a child. Her voice and performance are still top notch and I didn’t hear her make any age-related jokes, though her audience was a bit up there in years. The former Newport resident drew a nice-sized crowd to King’s Park. Unfortunately, Cowsill seemed to rely more on random cover songs than her own or even Cowsills material. Next up was Yes at the Newport Concert Series. This bunch just looks ancient. Despite the fact that I thought they might break a hip or need CPR on stage, they too put on an amazing show and pulled off great live versions of the Fragile and Close To The Edge albums in their entirety. -

Top 10 Shows at the Newport Folk Fest

Top 10 Shows at the Newport Folk Fest Every July in Rhode Island, The City By The Sea becomes electric with some of the best musicians on the planet coming to play Fort Adams. The Newport Folk Festival has reemerged as one of the premier stops of the summer music festival season. Famous for being the site of Bob Dylan’s highly amplified rock ‘n’ roll performance back in 1965, the festival has also played host to blues legend Son House, Elvis Costello, Jackson Browne, My Morning Jacket and Beck. To give you a guide of what you can’t miss this time around, here are my 10 things you have to check out at this year’s Newport Folk Festival: 10.) All Newport’s Eve @ The Newport Blues Café The night before the official start of the festival on July 24, there will be a stacked bill at The Newport Blues Café on 286 Thames Street featuring everyone’s favorite new Nashville musician by way of Providence, Joe Fletcher and his band of Wrong Reasons, fellow Nashville resident J.P. Harris and his Tough Choices, Philadelphia folk phenom Langhorne Slim, fellow Philadelphians Toy Soldiers, Dead Confederate’s T. Hardy Morris, Dallas’ Andrew Combs, The Deslondes from New Orleans, Providence’s orchestral pop act Arc Iris and New England singer-songwriter Ian Fitzgerald. If you’re in the area this is surely a pre-festival party you don’t want to miss. 9.) The After Parties One part of The Newport Folk Festival that makes it so special are the shows buzzing around town after each day. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

David Crosby Santana Leon Russell Medeski Martin & Wood + Nels

BOOK REVIEWS Cowboys And Indies: The Epic History of the Record Industry Umphrey’s McGee artists, ranging from Johnny Cash to By Gareth Murphy THOMAS DUNNE BOOKS Similar Skin NOTHING TOO FANCY Dylan to U2 to Ringo. You Should Be So Gareth Murphy’s Cowboys And Indies: The Epic History of the Record It’s ironic that a bunch of Lucky, his solo debut, isn’t likely to alter Industry comes just as billed. The book starts off in the 19th century guys who grew up Tench’s reputation. Its dozen songs are with the scramble for technological innovation and the accompanying worshipping Michael all well-constructed and impeccably patent rights to a device capable of capturing and reproducing sound. Jordan’s Chicago Bulls played—Tench always has been, and Following the invention of the “talking-machine,” the challenge turns would make a record that remains, a hell of a pianist and organist, to how to best realize its commercial prospects. Murphy’s chronicle their rival Detroit Pistons (nicknamed and a team of ace players joins him extends into the 21st century, tracking the efforts of self-described “The Bad Boys”) would have loved. here—and smartly produced by “record men.” The danger in such an undertaking is that it could have come off as That’s what Umphrey’s McGee have Glyn Johns. Ranging from crisp pop too dry or academic. However, while Murphy’s book is certainly informative, it is here with their eighth studio album. to thrusting rockers to rootsy blues also breezy and flush with anecdotes, placing a particular focus on the major A heavy, unapologetic, rock-and-roll and R&B, it’s a likable enough musical trends and the executives who founded and ran the celebrated record exhibition from start to finish that will showcase. -

Acoustic Sounds Winter Catalog Update

VOL. 8.8 VOL. 2014 WINTER ACOUSTICSOUNDS.COM ACOUSTIC SOUNDS, INC. VOLUME 8.8 The world’s largest selection of audiophile recordings Published 11/14 THE BEATLES IN MONO BOX SET AAPL 379916 • $336.98 The Beatles get back to mono in a limited edition 14 LP box set! 180-gram LPs pressed in Germany by Optimal Media. Newly remastered for vinyl from the analogue tapes by Sean Magee and Steve Berkowitz. The release includes all nine original mono mixed U.K. albums plus the original American- Cut to lacquer on a VMS80 lathe compiled mono Magical Mystery Tour and the Mono Masters, a three LP collection of Exclusive 12” 108-page hardbound book non-album tracks also compiled and mastered from the original analogue tapes. with rare studio photos! All individual albums available. See acousticsounds.com for details. FOUR MORE FROM THE FAB FOUR New LP Reissues - Including QRP Pressings! The below four Beatles LPs will be pressed in two separate runs. First up are 10,000 European-pressed copies. After those are sold through, the label will then release the Quality Record Pressings-pressed copies. All four albums are 180-gram double LPs! The Beatles 1967-1970 The Beatles 1962-1966 1 Love ACAP 48448 $35.98 ACAP 48455 $35.98 ACAP 60079 $35.98 ACAP 48509 $48.98 (QPR-pressed version; (QPR-pressed version; (QPR-pressed version; (QPR-pressed version; coming sometime in 2015) coming sometime in 2015) coming sometime in 2015) coming sometime in 2015) ACAP 484480 $35.98 ACAP 484550 $35.98 ACAP 600790 $35.98 ACAP ACAP 485090 $48.98 (European-pressed version; (European-pressed -

Order Form Full

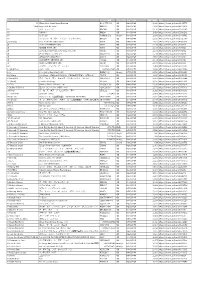

INDIE ROCK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 68 TWO PARTS VIPER COOKING VINYL RM128.00 *ASK DISCIPLINE & PRESSURE GROUND SOUND RM100.00 10, 000 MANIACS IN THE CITY OF ANGELS - 1993 BROADC PARACHUTE RM151.00 10, 000 MANIACS MUSIC FROM THE MOTION PICTURE ORIGINAL RECORD RM133.00 10, 000 MANIACS TWICE TOLD TALES CLEOPATRA RM108.00 12 RODS LOST TIME CHIGLIAK RM100.00 16 HORSEPOWER SACKCLOTH'N'ASHES MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 1975, THE THE 1975 VAGRANT RM140.00 1990S KICKS ROUGH TRADE RM100.00 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS VIRGIN RM132.00 31 KNOTS TRUMP HARM (180 GR) POLYVINYL RM95.00 400 BLOWS ANGEL'S TRUMPETS & DEVIL'S TROMBONE NARNACK RECORDS RM83.00 45 GRAVE PICK YOUR POISON FRONTIER RM93.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S BOMB THE ROCKS: EARLY DAYS SWEET NOTHING RM142.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S TEENAGE MOJO WORKOUT SWEET NOTHING RM129.00 A CERTAIN RATIO THE GRAVEYARD AND THE BALLROOM MUTE RM133.00 A CERTAIN RATIO TO EACH... (RED VINYL) MUTE RM133.00 A CITY SAFE FROM SEA THROW ME THROUGH WALLS MAGIC BULLET RM74.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER BAD VIBRATIONS ADTR RECORDS RM116.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR THOSE WHO HAVE HEART VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER HOMESICK VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD (PIC) VICTORY RECORDS RM111.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER WHAT SEPARATES ME FROM YOU VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVES HAVE YOU SEEN MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX? TOPSHELF RM103.00 A LIFE ONCE LOST IRON GAG SUBURBAN HOME RM99.00 A MINOR FOREST FLEMISH ALTRUISM/ININDEPENDENCE (RS THRILL JOCKEY RM135.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS TRANSFIXIATION DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS WORSHIP DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A SUNNY DAY IN GLASGOW SEA WHEN ABSENT LEFSE RM101.00 A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN ATOMOS KRANKY RM128.00 A.F.I. -

URL 44 When Your Heart Stop

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 44 When Your Heart Stops Beating B000775402 CD ROCK/POP 1,890 https://tower.jp/item/2131775 1984 Rage with No Name DRR023 CD ROCK/POP 2,890 https://tower.jp/item/4619808 !!! アズ イフ(+1) BRC481 CD ROCK/POP 2,111 https://tower.jp/item/3968983 !!! R!M!X!S BRE46 CD ROCK/POP 1,429 https://tower.jp/item/3330291 !!! As If(LP) WARPLP260 Analog ROCK/POP 2,890 https://tower.jp/item/3969742 !!! ストレンジ ウェザー、イズント イット?(+1) BRC261 CD ROCK/POP 2,095 https://tower.jp/item/2720586 (((Vluba))) Exile to Another Dimension MA16 CD ROCK/POP 1500 https://tower.jp/item/4495959 @ L'URLO INTERISTA (JP) GAR2 CD ROCK/POP 2,143 https://tower.jp/item/809822 @ GRAZIE ROMA (JP) GAR3 CD ROCK/POP 2,143 https://tower.jp/item/809823 @ IL MEGLIO DI MUSICA & GOAL VOL (JP) GRO15 CD ROCK/POP 2,143 https://tower.jp/item/809832 @ ナイトクラブ スプラッシュ NACL1159 CD ROCK/POP 2,718 https://tower.jp/item/534908 @ GENOA NEL CUORE(JP) GAR13 CD ROCK/POP 2,500 https://tower.jp/item/809830 @ GRANDE FIORENTINA (JP) GRO12 CD ROCK/POP 2,143 https://tower.jp/item/809829 @ URRA' SAMPDORIA! (JP) GRO14 CD ROCK/POP 2,143 https://tower.jp/item/809831 +/- スロウン イントゥ ザ ファイア YOUTH88 CD ROCK/POP 1429 https://tower.jp/item/2639987 1 Girl Nation Unite(US) 60234102042 CD ROCK/POP 1,890 https://tower.jp/item/4221260 10cc 10cc (180g Red Vinyl)(LP) BADLP006 Analog ROCK/POP 2,790 https://tower.jp/item/3534933 120 Days 120 Days ~神秘と幻想の120日 <期間生産限定盤>(LTD/+2) TRCP8 CD ROCK/POP 1886 https://tower.jp/item/2248474 2 Many DJ's アズ ハード オン レディオ ソウルワックス パート2 HSE30042 CD ROCK/POP 2,300 https://tower.jp/item/1052099 -

CONOR OBERST Core of What I Do, but I Always Think That I the Bright Eyes Frontman Releases a New Solo Album Write Folk Songs

ISSUE #35 MMUSICMAG.COM ISSUE #35 MMUSICMAG.COM Q&A part of the process. By 2004 or 2005 Nick I can pick out things to dress it up. I start Why? was also part of the process. By then, the adding words and other embellishments. It’s not a struggle—it’s really fun. For me, three of us functioned as a band. And when my best work comes out very naturally from there are contributions to that extent, they So the music comes first. being patient and waiting for access to that deserve the credit for it. Bright Eyes became The melodies always come first. I sit with part of the brain. That’s what’s so exciting to a band, but it’s also me, solo. a guitar or at the piano, and once I have me. That’s what keeps me wanting to come the melody I start singing sounds, non- back for more. Why choose Jonathan Wilson? words—just vowel sounds. I get the chord I went through a pretty extensive process progression fluid, and then I’ll walk around Why select Dawes as your live band? attempting to choose who would produce with it for a few days or weeks. Then I try Jonathan introduced me to them—he the album. Jonathan, being one of my friends, out lyrics and find the phrasing that fits produced their two albums. They have was among them. He produced the Dawes into the melodies. the same atmosphere and style as I do—I records, and I like what he did with those. -

Album of the Week: Spoon’S They Want My Soul,Top 10

Album of the Week: Spoon’s They Want My Soul The best success a band can have is through consistency. I’m not talking about playing the same style in each album you put out, but instead putting out quality music while not being afraid to push boundaries and try new things. Coming a long way from the lo-fi punkish alternative rock sound of their debut alum Telephono back in 1996, Spoon are back with their first album in four years with They Want My Soul. It might not be as commercial sounding as their chart topper Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga that came out in 2007 or as raw and risk-taking as their earlier material, but Spoon’s new album shows originality, proving that over time they haven’t strayed from their artistic identity. They call it rock & roll; I just think it’s a breath of fresh air in a year of highs and lows. Releasing their first album off of a new label after leaving a long-time relationship with Merge Records to join Loma Vista Recordings, Spoon is part of an eclectic brand that suits their style perfectly. A few tracks are straight-up rockers with forceful guitars riffs while others offer a mellow take with a heavy base of synth and keys. You can’t deny that front man Britt Daniel still brings his Sinatra beatnik soul, putting his heart into every track over the wonderful rhythms. There’s still that trademark groove that sets Spoon apart from a lot of other bands. -

Natalie Merchant, the Felice Brothers, Laura Marling and Others Join Conor Oberst & Friends at Holiday Cheer for FUV at the Beacon Theatre on December 8Th

Music discovery starts here Natalie Merchant, The Felice Brothers, Laura Marling And Others Join Conor Oberst & Friends at Holiday Cheer for FUV At the Beacon Theatre on December 8th New York, NY - The tenth annual Holiday Cheer for FUV concert starring Conor Oberst & Friends features an impressive list of "friends." Joining Conor onstage at the Beacon Theatre, on Monday, December 8th at 8 p.m. will be Natalie Merchant, The Felice Brothers, Laura Marling, The Lone Bellow, and Jonathan Wilson. Tickets for the concert, which benefits WFUV (90.7 FM/wfuv.org), New York's musically innovative public radio station, are on sale through Ticketmaster.com, Ticketmaster Charge By Phone (1-866-858-0008), all Ticketmaster Outlets and www.beacontheatre.com. Natalie Merchant, first known as the voice of 10,000 Maniacs, is an activist and singer-songwriter whose best-selling albums include Tigerlily, Ophelia, and this year's Natalie Merchant. The Felice Brothers, like Merchant from upstate New York, are infectious live performers who released two of their albums, The Felice Brothers and Yonder Is the Clock on Oberst's Team Love label. In her brief career Laura Marling has released four albums, three of which have been nominated for Britain's prestigious Mercury Prize. The Brooklyn-based trio, The Lone Bellow, who have earned critical acclaim for their soulful songwriting and supple harmonies, will release their second album in January. California musician/producer Jonathan Wilson has released four albums as a solo artist and produced numerous albums, including Conor Obert's most recent, Upside Down Mountain. "Last year's concert with Iron & Wine and Friends set a high bar for us," said WFUV Program Director Rita Houston.