Reassessing the Bunbury Bombing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Leadership—Perspectives and Practices

Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Edited by Paul ‘t Hart and John Uhr Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/public_leadership _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Public leadership pespectives and practices [electronic resource] / editors, Paul ‘t Hart, John Uhr. ISBN: 9781921536304 (pbk.) 9781921536311 (pdf) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Leadership Political leadership Civic leaders. Community leadership Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t. Uhr, John, 1951- Dewey Number: 303.34 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Images comprising the cover graphic used by permission of: Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development Australian Associated Press Australian Broadcasting Corporation Scoop Media Group (www.scoop.co.nz) Cover graphic based on M. C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935 (Lithograph). Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

Premiers of Western Australia?

www.elections.wa.gov.au Information sheet State government Premiers of Western Australia? Rt. Hon. Sir John Forrest (afterwards Lord) PC, GCMG 20 Dec 1890 – 14 Feb 1901 Hon. George Throssel CMG 14 Feb 1901 – 27 May 1901 Hon. George Leake KC, CMG 27 May 1901 – 21 Nov 1901 Hon Alfred E Morgans 21 Nov 1901 – 23 Dec 1901 Hon. George Leake KC, CMG 23 Dec 1901 – 24 June 1902 Hon. Walter H James KC, KCMG 1 July 1902 – 10 Aug 1904 Hon. Henry Daglish 10 Aug 1904 – 25 Aug 1905 Hon. Sir Cornthwaite H Rason 25 Aug 1905 – 1 May 1906 Hon. Sir Newton J Moore KCMG 7 May 1906 – 16 Sept 1910 Hon. Frank Wilson CMG 16 Sept 1910 – 7 Oct 1911 Hon. John Scaddan CMG 7 Oct 1911 – 27 July 1916 Hon. Frank Wilson CMG 27 July 1916 – 28 June 1917 Hon. Sir Henry B. Lefroy KCMG 28 June 1917 – 17 Apr 1919 Hon. Sir Hal P Colebatch CMG 17 Apr 1919 – 17 May 1919 Hon. Sir James Mitchell GCMG 17 May 1919 – 16 Apr 1924 Hon. Phillip Collier 17 Apr 1924 – 23 Apr 1930 Hon. Sir James Mitchell GCMG 24 Apr 1930 – 24 Apr 1933 Hon. Phillip Collier 24 Apr1933 – 19 Aug 1936 Hon. John Collings Wilcock 20 Aug 1936 – 31 July 1945 Hon. Frank JS Wise AO 31 July 1945 – 1 Apr 1947 Hon. Sir Ross McLarty KBE, MM 1 Apr 1947 – 23 Feb 1953 Hon. Albert RG Hawke 23 Feb 1953 – 2 Apr 1959 Hon. Sir David Brand KCMG 2 Apr 1959 – 3 Mar 1971 Hon. -

COURT AC, HON. RICHARD FAIRFAX Richard Was Born in 1947

COURT AC, HON. RICHARD FAIRFAX Richard was born in 1947 to Lady Rita and Sir Charles Court. He was educated at Dalkeith Primary School and Hale School and graduated with a Commerce degree from the University of Western Australia in 1968. He worked in the United States of America at the American Motors Corporation and Ford Motor Company to gain further management training. On his return to Western Australia he started a number of small businesses in fast food and boating. Richard was MLA (Liberal Party) for Nedlands WA from 1982 – 2001 and was Premier and Treasurer of Western Australia from 1993 – 2001. He retired from Parliament after 19 years as the Member for Nedlands. He was appointed Companion in the General Division of the Order of Australia in June 2003 for service to the Western Australian Parliament and to the community, particularly the indigenous community, and in the areas of child health research and cultural heritage and to economic development through negotiating major resource projects including new gas markets furthering the interests of the nation as a whole. MN ACC meterage / boxes Date donated CIU file Notes 2677 7394A 15.8 m 25 May 2001 BA/PA/02/0066 Boxes 13, 14, 17, 42, 59 and 83 returned to donor in 2012 SUMMARY OF CLASSES FILES – listed as received from donor Box No. DESCRIPTION ACC 7394A/1 FILES :Mining Act and royalties 1982-1990; Mining Association Chamber of Mines 1982-1992; Iron ore mining, magnesium plant; Mining Amendment Act 1987-1990; Mines dept 1988-1992;Chamber of Mines; Mining 1983- 1987; Mining 1988-1992;Small -

The Repatriation of Yagan : a Story of Manufacturing Dissent

Law Text Culture Volume 4 Issue 1 In the Wake of Terra Nullius Article 15 1998 The repatriation of Yagan : a story of manufacturing dissent H. McGlade Murdoch University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation McGlade, H., The repatriation of Yagan : a story of manufacturing dissent, Law Text Culture, 4, 1998, 245-255. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol4/iss1/15 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The repatriation of Yagan : a story of manufacturing dissent Abstract kaya yarn nyungar gnarn wangitch gnarn noort balaj goon kaart malaam moonditj listen Nyungars, I tell you, our people, our brother he come home, we lay his head down ... Old Nyungar men are singing, and the clapping sticks can be heard throughout Perth's international airport late in the night. There are up to three hundred Nyungars who have come to meet the Aboriginal delegation due to arrive on the 11pm flight from London. The delegation are bringing home the head of Yagan, the Nyungar warrior. This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol4/iss1/15 The Repatriation ofYagan: a Story of Manufaduring Dissent Hannah McGlade kaya yarn nyungar gnarn wangitch gnarn noort balaj goon kaart malaam moonditj listen Nyungars, I tell you, our people, our brother he come home, we lay his head down ... Old Nyungar men are singing, and the clapping sticks can be heard throughout Perth's international airport late in the night. -

Collection Name

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives – Collection Listing RESTRICTED MN 1301 Acc. 7153A SIR CHARLES COURT COLLECTION Charles Walter Michael Court was born in Sussex, England, on September 29, 1911, and migrated to Australia with his parents while a baby. The family settled in Perth and Sir Charles attended primary school in Leederville and then Perth Boys’ School. He was interested in music from an early age and joined the RSL Memorial Band at the age of 12. A talented cornet player he won the brass solo division of the 1928 national band competition. His interest in music was a lifelong passion and he played wind instruments in several orchestras. After leaving school, Sir Charles studied accountancy, becoming a founding partner in the firm Hendry, Rae and Court in 1938 where he retained an office until he was well into his 80s. In 1936, he married Rita Steffanoni and, in 1940, enlisted in the army as a private. Sir Charles rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel by the time of his discharge in 1946, after distinguished service in the Pacific. He had five sons, Victor, Barry, Ken, Richard and Geoffrey with his first wife Rita, who died in 1992. In 1953, Sir Charles began his political career by winning the seat of Nedlands. Within three years of his election to parliament, Sir Charles became Deputy Leader of the Opposition, and when the Liberal – Country Party government of David Brand was elected in 1959, he became Minister for Industrial Development, the North West and Railways. Under his tenure as minister, the Ord River scheme progressed, the mining industry began in the Pilbara and the Kwinana industrial strip developed. -

8 April 1975

[Tuesday, 8 April, 1975.J 5535 Mr RUSHTON replied: (2) When Will the primary school be I have now finalised my pro- built at Kardinys, which will re- granmme of visiting the 138 local lieve the Carawatha problem? authorities as proposed. in the The HoIn. 0. C. Macfl'JNON replied: company of the member for Avon (1) Yes. (Mr Ken McIver) and the mem- (2) The construction of a new school ber for the Central Province (Mr at Kardlnya, has been listed for H. W. Gayfer), I completed the consideration. Priority must be programme last night by visiting given to other schools with more the Northam Shire Council. temporary accommodation or Mr BRYCE: Mr Speaker- greater growth potential. A final The SPEAKER: Order! Will the decision, therefore, must be de- member resume his seat? pendent on the degree to which Mr Bryce: Secrecy does not stop 'with costs of buildings continue to the Government. escalate. Sir Charles Court: That is a nice 2. INDUSTRIALL GASES thing to say about the Speaker. The SPEAKER: May I: ask the mem- Storage Hazards ber for Ascot to repeat his state- The Hon. R. H. C. STUBBS, to the ment? Minister for Education representing Mr BRYCE: I said it appears secrecy the Minister for Labour and Industry: does not stop with the Govern- With reference to my question on ment. the 19th March, 1975, relating to the storage of bottled gases, and Sir Charles Court: That is a nice one. as there are no mining regula- The SPEAKER: Of course, the impli- tions for the control of such, is cation is very plain to me, and the there any regulation under any public at large. -

?Igiaatinrp Asambtu Procedure Has Been Followed in This Case

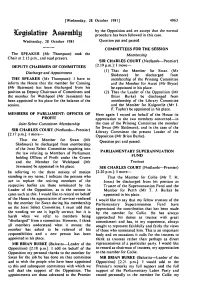

[Wednesday, 28 October 1981] 496346 by the Opposition and we accept that the normal ?igiaatinrp Asambtu procedure has been followed in this case. Wednesday, 28 October 1981 Question put and passed. COMMITT'EES FOR THE SESSION The SPEAKER (Mr Thompson) took the Membership Chair at 2.1$ p.m., and read prayers. SIR CHARLES COURT (Nedlands-Premier) DEPUTY CHAIRMEN OF COMMITTEES [2.19 p.m.]: I move- Discharge and Appointment (I) That the Member For Swan (Mr Skidmore) be discharged From THE SPEAKER (Mr Thompson): I have to membership of the Printing Committee inform the House that the member for Canning and the Member for Ascot (Mr Bryce) (Mr Bateman) has been discharged from his be appointed in his place. position as Deputy Chairman of Committees and (2) That the Leader of the Opposition (Mr the member for Welshpool (Mr Jamieson) has Brian Burke) be discharged from been appointed in his place for the balance of the membership of the Library Committee session. and the Member for Kalgoorlie (Mr I. F,. Taylor) be appointed in his place. MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT: OFFICES OF Here again I record on behalf of the House its PROFIT appreciation to the two members concerned-in Joint Select Committee: Membership the case of the Printing Committee the member for Swan (Mr Skidmore), and in the case of the SIR CHARLES COURT (Nedlands-Premier) Library Committee the present Leader of the [2.17 pm.]: I move- Opposition (Mr Brian Burke). That the Member for Swan (Mr Question put and passed. Skidmore) be discharged from membership of the Joint Select Committee inquiring into PARLIAMENTARY SUPERANNUATION the law relating to Members of Parliament FUND holding Offices of Profit under the Crown and the Member for Welshpool (Mr Trustees Jamieson) be appointed in his place. -

![9/1/77 [1] Folder Citation: Collection](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5867/9-1-77-1-folder-citation-collection-4535867.webp)

9/1/77 [1] Folder Citation: Collection

9/1/77 [1] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 9/1/77 [1]; Container 39 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf -···--· ----- ~ " WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT memo From Bourne to the Pres:rent (1 page) re:Messag~ 9/1/77 A from Andy Young { ( or l7 '1-3 i I i FI E LOC TION , ~r~er ~res1dential Papers- Staff Offcies, Office of the Staff Sec.- Pres. Hand f"riting File 9/1/77 [1] Box • "17 RESTRICTI O N CODES {A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'governing access to national security information. {B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. {C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION NA FORM 14 2 9 (6-85) CONFIDENTtAL :I:BE PRESIDENX HAS SEJ~J . l. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON September 1, 1977 MEMORANDUM TO THE PRESIDENT FROM: PETER BOURNE f. 8 · SUBJECT: MESSAGE FROM ANDY YOUNG Mary called me from the Desertification Conference in Nairobi where she had dinner last night with Andy Young. Andy wanted me to pass on to you that his call to you earlier this week from South Africa was a "game" for the benefit of the people listening on the tapped phone he called you on. He said he hoped you realized this and to tell you that the answers you gave were perfect in terms of what he wanted them to hear. -

Iron Country: Unlocking the Pilbara

Iron country: Unlocking the Pilbara DAVID LEE A PUBLIC POLICY ANALYSIS PRODUCED FOR 09 THE MINERALS COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA JUNE 2015 Iron country: Unlocking the Pilbara DAVID LEE MINERALS COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA June 2015 Dr David Lee is the Director of the Historical Publications and Research Unit, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. He is the author of Australia and the World in the Twentieth Century, Melbourne, 2005 and Stanley Melbourne Bruce: Australian Internationalist, London and New York, 2010. He is currently researching Australia’s post-1960 mining booms and a collaborative biography of Sir John Crawford. The Minerals Council of Australia represents Australia’s exploration, mining and minerals processing industry, nationally and internationally, in its contribution to sustainable economic and social development. This publication is part of the overall program of the MCA, as endorsed by its Board of Directors, but does not necessarily reflect the views of individual members of the Board. ISBN 978-0-9925333-4-2 MINERALS COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA Level 3, 44 Sydney Ave, Forrest ACT 2603 (PO Box 4497, Kingston ACT Australia 2604) P. + 61 2 6233 0600 | F. + 61 2 6233 0699 W. www.minerals.org.au | E. [email protected] Copyright © 2015 Minerals Council of Australia. All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher and copyright holders. -

West Australian Thursday 9/11/2006 Brief: PARLWA WA Page: 4 Section: Supplements Region: Perth Circulation: 205,610 Type: Capital City Daily Size: 234.29 Sq.Cms

West Australian Thursday 9/11/2006 Brief: PARLWA_WA Page: 4 Section: Supplements Region: Perth Circulation: 205,610 Type: Capital City Daily Size: 234.29 sq.cms. Published: MTWTFS- CHARLES COURT Cometh the hour, cometh the man. union movement had built up under Charles WalterMichaelCourt's successive Labor governments. hour arrived in 1953 when the up- He confronted the powerful Collie and-coming chartered accountant miners' union and the waterside was drafted to take on the seat of workers. Nedlands for the Liberal Party. Later, as premier from 1974 to He says he agreed to serve two 1982, Sir Charles introduced the parliamentary terms, then six years, notorious section 54B of the Police and planned to return to his new Act under which it was an offence partnership in the firm Hendry, Rae punishable by a month's jail for more and Court. than three people to meet in public But in the lead-up to the 1959 without a permit. election, Liberal leader David Brand Sir Charles was fond of saying that asked him to write the party's policy leaders were meant to lead and he for developing WA's North-West and was not what nowadays would be then to take it to the people. regarded as a consensus politician. Western Australia had up until His controversial decision to use then been a mendicant State, reliant the police and the State Emergency on Federal tax support. Service to ensure a mining company The coalition won the poll and Mr fulfilled its obligations to drill on the Court's time really arrived when he Aboriginal-run Noonkanbah station in immediately took on the ministries of the Kimberley was a hallmark of his industrial development, the North- political style. -

Nickel Queen End Credits

CAST Meg Blake Googie Withers Claude Fitzherbert John Laws Ed Benson Alfred Sandor Harry Phillips Ed Devereaux Andy Kyle Peter Gwynne Betsy Benson Doreen Warburton Roy Olding Tom Oliver Jenny Blake Joanna McCallum Arthur Ross Thompson Beatrice Whittaker Eileen Colocott Ernest Whittaker Maurice Ogden Martin Mas Masters Kay Christine Mearing Toni Sue Hartley Sue Tasma Michael Cheryl Jenny Tuurenhout Pat Eleanor Proud Mary Joan McGrath Gerry Des Sambo Jim Ross Lightfoot Dave David Sarll Pilot Doug Farley T.V. Interviewer John Hudson Lady Bartholemew Nancy Nunn Sir Henry Bartholemew Poole Johnson George George Maw Ken Ken Johns Sam Harry Argus Lionel Richard Argus Keith David Tuck Colin Dave Broadfield Girlfriend Harriet Pace Band Leader Ossie Sanderson Radio Interviewer Ric Rogers Sheila Ashby Tricia Phillips Jill Carruthers Jan Olding Harriet Price Molly Hungerford Sylvia Turnbull Shirley Gershon Miss Levine Carol Minear Mary Peters Peta Maitland Lady Bill Hook Vanya Geddes George Ashby Geoff Jacoby Victa Norman Jones Shareholder Sam Harris Shareholder Ron McGuire Shareholder Bill Ward Shareholder Norman Jackson Chairman Racing Club Charles Lee Steere Carol Nixon Jenny Cullen Bus Driver Peter Rankin Secretary Stock Exchange Graham Bowra Perth Salesman Ray Toby Kalgoorlie Salesman Charles Brown Sir Rollo Anderson Charles Harper and Sir David Brand Premier of Western Australia The Hon. Charles Court Minister for Industrial Development The Hon. Arthur Griffith Minister for Mines The Producers wish to thank the Government of Western Australia for its valuable assistance in the making of this film. THE END Copyright © MCMLXXI Woomera Productions. -

Statue Wars in Western Australia

Public History Review Dark Pasts in the Landscape: Vol. 28, 2021 Statue Wars in Western Australia Jenny Gregory DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v28i0.7504 Statues preserve the memory of leaders and heroes and transmit archetypal stories. They represent the past, often so far past that the values represented by the statue hold no meaning for passers-by. At times, however, statues evoke new memories that replace or build on the old.1 Then they become visible again, particularly in moments of crisis, when ‘they polarise public life by serving as lightning rods of social conflict’.2 When statues are removed it is as if they are being excised from history. In Eastern Europe, for example, statues tumbled as regimes collapsed after the disintegration of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. In Iraq the statue of Saddam Hussein in Bagdad was toppled in 2003 during the © 2021 by the author(s). This Iraq War and in Spain statues of the dictator Franco were destroyed in 2005 in an attempt is an Open Access article 3 distributed under the terms to erase his memory and the memory of his regime. of the Creative Commons The idea of toppling statues has gathered strength around the world. In the largest wave Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https:// of student activism in democratic South Africa the statue of Rhodes, now seen as a symbol creativecommons.org/licenses/ of colonial power and generations of black oppression, was removed from the University of by/4.0/), allowing third parties Cape Town in 2014.4 A statue of Rhodes in Oxford remains a target of student protest.5 In the to copy and redistribute the United States in recent years, an escalating climate of racial tension and the emergence of the material in any medium 6 or format and to remix, #BlackLivesMatter movement, has led to the removal of or threats to Confederate statues.