Determinism and Indeterminism: from Biology to Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At Least in Biophysical Novelties Amihud Gilead

The Twilight of Determinism: At Least in Biophysical Novelties Amihud Gilead Department of Philosophy, Eshkol Tower, University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838 Email: [email protected] Abstract. In the 1990s, Richard Lewontin referred to what appeared to be the twilight of determinism in biology. He pointed out that DNA determines only a little part of life phenomena, which are very complex. In fact, organisms determine the environment and vice versa in a nonlinear way. Very recently, biophysicists, Shimon Marom and Erez Braun, have demonstrated that controlled biophysical systems have shown a relative autonomy and flexibility in response which could not be predicted. Within the boundaries of some restraints, most of them genetic, this freedom from determinism is well maintained. Marom and Braun have challenged not only biophysical determinism but also reverse-engineering, naive reductionism, mechanism, and systems biology. Metaphysically possibly, anything actual is contingent.1 Of course, such a possibility is entirely excluded in Spinoza’s philosophy as well as in many philosophical views at present. Kant believed that anything phenomenal, namely, anything that is experimental or empirical, is inescapably subject to space, time, and categories (such as causality) which entail the undeniable validity of determinism. Both Kant and Laplace assumed that modern science, such as Newton’s physics, must rely upon such a deterministic view. According to Kant, free will is possible not in the phenomenal world, the empirical world in which we 1 This is an assumption of a full-blown metaphysics—panenmentalism—whose author is Amihud Gilead. See Gilead 1999, 2003, 2009 and 2011, including literary, psychological, and natural applications and examples —especially in chemistry —in Gilead 2009, 2010, 2013, 2014a–c, and 2015a–d. -

Natural Kinds and Concepts: a Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account

Natural Kinds and Concepts: A Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account Ingo Brigandt Abstract: In this chapter I lay out a notion of philosophical naturalism that aligns with prag- matism. It is developed and illustrated by a presentation of my views on natural kinds and my theory of concepts. Both accounts reflect a methodological naturalism and are defended not by way of metaphysical considerations, but in terms of their philosophical fruitfulness. A core theme is that the epistemic interests of scientists have to be taken into account by any natural- istic philosophy of science in general, and any account of natural kinds and scientific concepts in particular. I conclude with general methodological remarks on how to develop and defend philosophical notions without using intuitions. The central aim of this essay is to put forward a notion of naturalism that broadly aligns with pragmatism. I do so by outlining my views on natural kinds and my account of concepts, which I have defended in recent publications (Brigandt, 2009, 2010b). Philosophical accounts of both natural kinds and con- cepts are usually taken to be metaphysical endeavours, which attempt to develop a theory of the nature of natural kinds (as objectively existing entities of the world) or of the nature of concepts (as objectively existing mental entities). However, I shall argue that any account of natural kinds or concepts must an- swer to epistemological questions as well and will offer a simultaneously prag- matist and naturalistic defence of my views on natural kinds and concepts. Many philosophers conceive of naturalism as a primarily metaphysical doc- trine, such as a commitment to a physicalist ontology or the idea that humans and their intellectual and moral capacities are a part of nature. -

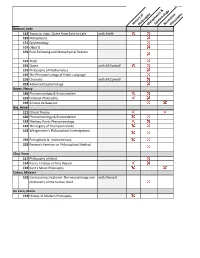

History of Philosophymetaphysics & Epistem Ology Norm Ative

HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Azzouni, Jody 114 Topics in Logic: Quine from Early to Late with Smith 120 Metaphysics 131 Epistemology 191 Objects 191 Rule-Following and Metaphysical Realism 191 Truth 191 Quine with McConnell 191 Philosophy of Mathematics 192 The Phenomenology of Public Language 195 Chomsky with McConnell 292 Advanced Epistemology Bauer, Nancy 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 191 Feminist Philosophy 192 Simone de Beauvoir Baz, Avner 121 Ethical Theory 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 192 Merleau Ponty Phenomenology 192 The Legacy of Thompson Clarke 192 Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations 292 Perceptions & Indeterminacy 292 Research Seminar on Philosophical Method Choi, Yoon 117 Philosophy of Mind 164 Kant's Critique of Pure Reason 192 Kant's Moral Philosophy Cohen, Michael 192 Conciousness Explored: The neurobiology and with Dennett philosophy of the human mind De Caro, Mario 152 History of Modern Philosophy De HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Car 191 Nature & Norms 191 Free Will & Moral Responsibility Denby, David 133 Philosophy of Language 152 History of Modern Philosophy 191 History of Analytic Philosophy 191 Topics in Metaphysics 195 The Philosophy of David Lewis Dennett, Dan 191 Foundations of Cognitive Science 192 Artificial Agents & Autonomy with Scheutz 192 Cultural Evolution-Is it Darwinian 192 Topics in Philosophy of Biology: The Boundaries with Forber of Darwinian Theory 192 Evolving Minds: From Bacteria to Bach 192 Conciousness -

Causality and Determinism: Tension, Or Outright Conflict?

1 Causality and Determinism: Tension, or Outright Conflict? Carl Hoefer ICREA and Universidad Autònoma de Barcelona Draft October 2004 Abstract: In the philosophical tradition, the notions of determinism and causality are strongly linked: it is assumed that in a world of deterministic laws, causality may be said to reign supreme; and in any world where the causality is strong enough, determinism must hold. I will show that these alleged linkages are based on mistakes, and in fact get things almost completely wrong. In a deterministic world that is anything like ours, there is no room for genuine causation. Though there may be stable enough macro-level regularities to serve the purposes of human agents, the sense of “causality” that can be maintained is one that will at best satisfy Humeans and pragmatists, not causal fundamentalists. Introduction. There has been a strong tendency in the philosophical literature to conflate determinism and causality, or at the very least, to see the former as a particularly strong form of the latter. The tendency persists even today. When the editors of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy asked me to write the entry on determinism, I found that the title was to be “Causal determinism”.1 I therefore felt obliged to point out in the opening paragraph that determinism actually has little or nothing to do with causation; for the philosophical tradition has it all wrong. What I hope to show in this paper is that, in fact, in a complex world such as the one we inhabit, determinism and genuine causality are probably incompatible with each other. -

SPINOZA's ETHICS: FREEDOM and DETERMINISM by Alfredo Lucero

SPINOZA’S ETHICS: FREEDOM AND DETERMINISM by Alfredo Lucero-Montaño 1. What remains alive of a philosopher's thought are the realities that concern him, the problems that he addresses, as well as the questions that he poses. The breath and depth of a philosopher's thought is what continues to excite and incite today. However, his answers are limited to his time and circumstances, and these are subject to the historical evolution of thought, yet his principal commitments are based on the problems and questions with which he is concerned. And this is what resounds of a philosopher's thought, which we can theoretically and practically adopt and adapt. Spinoza is immersed in a time of reforms, and he is a revolutionary and a reformer himself. The reforming trend in modern philosophy is expressed in an eminent way by Descartes' philosophy. Descartes, the great restorer of science and metaphysics, had left unfinished the task of a new foundation of ethics. Spinoza was thus faced with this enterprise. But he couldn't carry it out without the conviction of the importance of the ethical problems or that ethics is involved in a fundamental aspect of existence: the moral destiny of man. Spinoza's Ethics[1] is based on a theory of man or, more precisely, on an ontology of man. Ethics is, for him, ontology. He does not approach the problems of morality — the nature of good and evil, why and wherefore of human life — if it is not on the basis of a conception of man's being-in-itself, to wit, that the moral existence of man can only be explained by its own condition. -

Consequences of Pragmatism University of Minnesota Press, 1982

estratto dal volume: RICHARD RORTY Consequences of Pragmatism University of Minnesota Press, 1982 INTRODUCTION 1. Platonists, Positivists, and Pragmatists The essays in this book are attempts to draw consequences from a prag- matist theory about truth. This theory says that truth is not the sort of thing one should expect to have a philosophically interesting theory about. For pragmatists, “truth” is just the name of a property which all true statements share. It is what is common to “Bacon did not write Shakespeare,” “It rained yesterday,” “E equals mc²” “Love is better than hate,” “The Alle- gory of Painting was Vermeer’s best work,” “2 plus 2 is 4,” and “There are nondenumerable infinities.” Pragmatists doubt that there is much to be said about this common feature. They doubt this for the same reason they doubt that there is much to be said about the common feature shared by such morally praiseworthy actions as Susan leaving her husband, Ameri- ca joining the war against the Nazis, America pulling out of Vietnam, Socrates not escaping from jail, Roger picking up litter from the trail, and the suicide of the Jews at Masada. They see certain acts as good ones to perform, under the circumstances, but doubt that there is anything gen- eral and useful to say about what makes them all good. The assertion of a given sentence—or the adoption of a disposition to assert the sentence, the conscious acquisition of a belief—is a justifiable, praiseworthy act in certain circumstances. But, a fortiori, it is not likely that there is something general and useful to be said about what makes All such actions good-about the common feature of all the sentences which one should ac- quire a disposition to assert. -

The Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85128-2 - The Cambridge Companion to the Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L. Hull and Michael Ruse Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to THE PHILOSOPHY OF BIOLOGY The philosophy of biology is one of the most exciting new areas in the field of philosophy and one that is attracting much attention from working scientists. This Companion, edited by two of the founders of the field, includes newly commissioned essays by senior scholars and by up-and- coming younger scholars who collectively examine the main areas of the subject – the nature of evolutionary theory, classification, teleology and function, ecology, and the prob- lematic relationship between biology and religion, among other topics. Up-to-date and comprehensive in its coverage, this unique volume will be of interest not only to professional philosophers but also to students in the humanities and researchers in the life sciences and related areas of inquiry. David L. Hull is an emeritus professor of philosophy at Northwestern University. The author of numerous books and articles on topics in systematics, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology, and naturalized epistemology, he is a recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Michael Ruse is professor of philosophy at Florida State University. He is the author of many books on evolutionary biology, including Can a Darwinian Be a Christian? and Darwinism and Its Discontents, both published by Cam- bridge University Press. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he has appeared on television and radio, and he contributes regularly to popular media such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Playboy magazine. -

A Rationalist Argument for Libertarian Free Will

A rationalist argument for libertarian free will Stylianos Panagiotou PhD University of York Philosophy August 2020 Abstract In this thesis, I give an a priori argument in defense of libertarian free will. I conclude that given certain presuppositions, the ability to do otherwise is a necessary requirement for substantive rationality; the ability to think and act in light of reasons. ‘Transcendental’ arguments to the effect that determinism is inconsistent with rationality are predominantly forwarded in a Kantian manner. Their incorporation into the framework of critical philosophy renders the ontological status of their claims problematic; rather than being claims about how the world really is, they end up being claims about how the mind must conceive of it. To make their ontological status more secure, I provide a rationalist framework that turns them from claims about how the mind must view the world into claims about the ontology of rational agents. In the first chapter, I make some preliminary remarks about reason, reasons and rationality and argue that an agent’s access to alternative possibilities is a necessary condition for being under the scope of normative reasons. In the second chapter, I motivate rationalism about a priori justification. In the third chapter, I present the rationalist argument for libertarian free will and defend it against objections. Several objections rest on a compatibilist understanding of an agent’s abilities. To undercut them, I devote the fourth chapter, in which I give a new argument for incompatibilism between free will and determinism, which I call the situatedness argument for incompatibilism. If the presuppositions of the thesis are granted and the situatedness argument works, then we may be justified in thinking that to the extent that we are substantively rational, we are free in the libertarian sense. -

Levitt Sample.Qxd

CHAPTER 1 Psychological Research The Whys and Hows of the Scientific Method CONSIDER THE FOLLOWING QUESTIONS AS YOU READ CHAPTER 1 • Why do psychologists use the scientific method? • How do psychologists use the scientific method? • What are the canons of the scientific method? • What is the difference between basic and applied research? • How do basic and applied research interact to increase our knowledge about behavior? As an instructor of an introductory psychology course for psychology majors, I ask my first-semester freshman students the question “What is a psychologist?” At the beginning of the semester, students typically say that a psychologist listens to other people’s problems to help them live happier lives. By the end of the semester and their first college course in psychology, these same students will respond that a psychologist studies behavior through research. These students have learned that psychology is a science that investigates behav - ior, mental processes, and their causes. That is what this book is about: how psychologists use the scientific method to observe and understand behavior and mental processes. The goal of this text is to give you a step-by-step approach to designing research in psy - chology, from the purpose of research (discussed in this chapter) and the types of questions psychologists ask about behavior, to the methods psychologists use to observe and under - stand behavior and describe their findings to others in the field. WHY PSYCHOLOGISTS CONDUCT RESEARCH Think about how you know the things you know. How do you know the earth is round? How do you know it is September? How do you know that there is a poverty crisis in some parts of Africa? There are probably many ways that you know these things. -

May 03 CI.Qxd

Philosophy of Chemistry by Eric Scerri Of course, the field of compu- hen I push my hand down onto my desk it tational quantum chemistry, does not generally pass through the which Dirac and other pioneers Wwooden surface. Why not? From the per- of quantum mechanics inadver- spective of physics perhaps it ought to, since we are tently started, has been increas- told that the atoms that make up all materials consist ingly fruitful in modern mostly of empty space. Here is a similar question that chemistry. But this activity has is put in a more sophisticated fashion. In modern certainly not replaced the kind of physics any body is described as a superposition of chemistry in which most practitioners are engaged. many wavefunctions, all of which stretch out to infin- Indeed, chemists far outnumber scientists in all other ity in principle. How is it then that the person I am fields of science. According to some indicators, such as talking to across my desk appears to be located in one the numbers of articles published per year, chemistry particular place? may even outnumber all the other fields of science put together. If there is any sense in which chemistry can The general answer to both such questions is that be said to have been reduced then it can equally be although the physics of microscopic objects essen- said to be in a high state of "oxidation" regarding cur- tially governs all of matter, one must also appeal to rent academic and industrial productivity. the laws of chemistry, material science, biology, and Starting in the early 1990s a group of philosophers other sciences. -

Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry

CALL FOR PAPERS First International Conference on Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry 25-27 June 2019 University of Paris Diderot, France Extended Deadline for Abstract Submission: 28 February 2019 The aim of this conference is to bring philosophers of biology and philosophers of chemistry together and to explore common grounds and topics of interest. We particularly welcome papers on (1) the philosophy of interdisciplinary fields between biology and chemistry; (2) historical case studies on the disciplinary divergence and convergence of biology and chemistry; and (3) the similarities and differences between philosophical approaches to biology and chemistry. Philosophy is broadly construed and includes epistemological, methodological, ontological, metaphysical, ethical, political, and legal issues of science. For a detailed description of possible topics, please see below and visit the conference website http://www.sphere.univ-paris-diderot.fr/spip.php?article2228&lang=en Instructions for Abstract Submission Submit a Word file including author name(s), affiliation, paper title, and an abstract of maximum 500 words by 28 February 2019 to Jean-Pierre Llored ([email protected]) . Registration If you are interested in participating, please register by sending an e-mail to Jean-Pierre Llored ([email protected]) before 30 April 2019. Venue Room 454A, Building Condorcet, University Paris Diderot, 4, rue Elsa Morante, 75013 Paris, France Sponsors CNRS; Laboratory SPHERE, Laboratory LIED, and Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Paris Diderot; Fondation de la Maison de la Chimie; Free University of Brussels; University of Lille Organizers Cécilia Bognon, Quentin Hiernaux, Jean-Pierre Llored, Joachim Schummer First international Conference on Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry 25-27 June 2019, University of Paris Diderot, France Description Background For much of the twentieth century, philosophy of science had almost exclusively been focused on physics and mathematics. -

Criminal Responsibility and Causal Determinism J

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 9 | Issue 1 2016 Criminal Responsibility and Causal Determinism J. G. Moore Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons This document is a corrected version of the article originally published in print. To access the original version, follow the link in the Recommended Citation then download the file listed under “Previous Versions." Recommended Citation J. G. Moore, Criminal Responsibility and Causal Determinism, 9 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 043 (2016, corrected 2016). Available at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol9/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Criminal Responsibility and Causal Determinism Cover Page Footnote This document is a corrected version of the article originally published in print. To access the original version, follow the link in the Recommended Citation then download the file listed under “Previous Versions." This article is available in Washington University Jurisprudence Review: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol9/ iss1/6 CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY AND CAUSAL DETERMINISM: CORRECTED VERSION J G MOORE* INTRODUCTION In analytical jurisprudence, determinism has long been seen as a threat to free will, and free will has been considered necessary for criminal responsibility.1 Accordingly, Oliver Wendell Holmes held that if an offender were hereditarily or environmentally determined to offend, then her free will would be reduced, and her responsibility for criminal acts would be correspondingly diminished.2 In this respect, Holmes followed his father, Dr.