Function Without Purpose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Kinds and Concepts: a Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account

Natural Kinds and Concepts: A Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account Ingo Brigandt Abstract: In this chapter I lay out a notion of philosophical naturalism that aligns with prag- matism. It is developed and illustrated by a presentation of my views on natural kinds and my theory of concepts. Both accounts reflect a methodological naturalism and are defended not by way of metaphysical considerations, but in terms of their philosophical fruitfulness. A core theme is that the epistemic interests of scientists have to be taken into account by any natural- istic philosophy of science in general, and any account of natural kinds and scientific concepts in particular. I conclude with general methodological remarks on how to develop and defend philosophical notions without using intuitions. The central aim of this essay is to put forward a notion of naturalism that broadly aligns with pragmatism. I do so by outlining my views on natural kinds and my account of concepts, which I have defended in recent publications (Brigandt, 2009, 2010b). Philosophical accounts of both natural kinds and con- cepts are usually taken to be metaphysical endeavours, which attempt to develop a theory of the nature of natural kinds (as objectively existing entities of the world) or of the nature of concepts (as objectively existing mental entities). However, I shall argue that any account of natural kinds or concepts must an- swer to epistemological questions as well and will offer a simultaneously prag- matist and naturalistic defence of my views on natural kinds and concepts. Many philosophers conceive of naturalism as a primarily metaphysical doc- trine, such as a commitment to a physicalist ontology or the idea that humans and their intellectual and moral capacities are a part of nature. -

History of Philosophymetaphysics & Epistem Ology Norm Ative

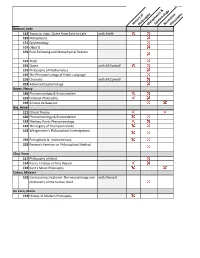

HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Azzouni, Jody 114 Topics in Logic: Quine from Early to Late with Smith 120 Metaphysics 131 Epistemology 191 Objects 191 Rule-Following and Metaphysical Realism 191 Truth 191 Quine with McConnell 191 Philosophy of Mathematics 192 The Phenomenology of Public Language 195 Chomsky with McConnell 292 Advanced Epistemology Bauer, Nancy 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 191 Feminist Philosophy 192 Simone de Beauvoir Baz, Avner 121 Ethical Theory 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 192 Merleau Ponty Phenomenology 192 The Legacy of Thompson Clarke 192 Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations 292 Perceptions & Indeterminacy 292 Research Seminar on Philosophical Method Choi, Yoon 117 Philosophy of Mind 164 Kant's Critique of Pure Reason 192 Kant's Moral Philosophy Cohen, Michael 192 Conciousness Explored: The neurobiology and with Dennett philosophy of the human mind De Caro, Mario 152 History of Modern Philosophy De HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Car 191 Nature & Norms 191 Free Will & Moral Responsibility Denby, David 133 Philosophy of Language 152 History of Modern Philosophy 191 History of Analytic Philosophy 191 Topics in Metaphysics 195 The Philosophy of David Lewis Dennett, Dan 191 Foundations of Cognitive Science 192 Artificial Agents & Autonomy with Scheutz 192 Cultural Evolution-Is it Darwinian 192 Topics in Philosophy of Biology: The Boundaries with Forber of Darwinian Theory 192 Evolving Minds: From Bacteria to Bach 192 Conciousness -

Why Terms Matter to Biological Theories: the Term “Origin” As Used by Darwin

Bionomina, 1: 58–60 (2010) ISSN 1179-7649 (print edition) www.mapress.com/bionomina/ Correspondence BIONOMINA Copyright © 2010 • Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-7657 (online edition) Why terms matter to biological theories: the term “origin” as used by Darwin Thierry HOQUET Département de Philosophie, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense, 200 Avenue de la République, 92001 Nanterre Cedex, France. <[email protected]>. Everybody now understands what Darwin meant when he published his epoch-making book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of favoured Races in the Struggle for life (1859). He, of course, meant evolution, i.e., the transformation of animals and plants, chance modifications, and speciation. Nevertheless, the very notion of “evolution” has aroused as much confusion as it has debate: some historians tend to suggest that Darwin intentionally avoided using the term, since it was supposedly full of progressive or embryological connotations; others claim that Darwin constantly employed the word (after all, they argue, the word “evolved” is the last one of the book). This disagreement regarding the supposed absence or presence of the term “evolution” is more than a sterile academic exercise: what is at stake in this debate is the very meaning of Darwin’s theory, as well as its relation to the contingent notions of “progress” and “development”. Darwin’s allegedly crystal-clear title is in fact perhaps the most commented part of the book. Ever since Darwin’s book first appeared, readers claimed that the book did not match its title. St. John Mivart suggested that the right question was not the “origin” but the “genesis” of species (1871); Edward Drinker Cope promoted the “origin of genera” and the “origin of the fittest” (1887); Theodor Eimer took up the question of the origin of species, but emphasized inheritance of acquired characters instead of natural selection (1888). -

Contrastive Empiricism

Elliott Sober Contrastive Empiricism I Despite what Hegel may have said, syntheses have not been very successful in philosophical theorizing. Typically, what happens when you combine a thesis and an antithesis is that you get a mishmash, or maybe just a contradiction. For example, in the philosophy of mathematics, formalism says that mathematical truths are true in virtue of the way we manipulate symbols. Mathematical Platonism, on the other hand, holds that mathematical statements are made true by abstract objects that exist outside of space and time. What would a synthesis of these positions look like? Marks on paper are one thing, Platonic forms an other. Compromise may be a good idea in politics, but it looks like a bad one in philosophy. With some trepidation, I propose in this paper to go against this sound advice. Realism and empiricism have always been contradictory tendencies in the philos ophy of science. The view I will sketch is a synthesis, which I call Contrastive Empiricism. Realism and empiricism are incompatible, so a synthesis that merely conjoined them would be a contradiction. Rather, I propose to isolate important elements in each and show that they combine harmoniously. I will leave behind what I regard as confusions and excesses. The result, I hope, will be neither con tradiction nor mishmash. II Empiricism is fundamentally a thesis about experience. It has two parts. First, there is the idea that experience is necessary. Second, there is the thesis that ex perience suffices. Necessary and sufficient for what? Usually this blank is filled in with something like: knowledge of the world outside the mind. -

The Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85128-2 - The Cambridge Companion to the Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L. Hull and Michael Ruse Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to THE PHILOSOPHY OF BIOLOGY The philosophy of biology is one of the most exciting new areas in the field of philosophy and one that is attracting much attention from working scientists. This Companion, edited by two of the founders of the field, includes newly commissioned essays by senior scholars and by up-and- coming younger scholars who collectively examine the main areas of the subject – the nature of evolutionary theory, classification, teleology and function, ecology, and the prob- lematic relationship between biology and religion, among other topics. Up-to-date and comprehensive in its coverage, this unique volume will be of interest not only to professional philosophers but also to students in the humanities and researchers in the life sciences and related areas of inquiry. David L. Hull is an emeritus professor of philosophy at Northwestern University. The author of numerous books and articles on topics in systematics, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology, and naturalized epistemology, he is a recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Michael Ruse is professor of philosophy at Florida State University. He is the author of many books on evolutionary biology, including Can a Darwinian Be a Christian? and Darwinism and Its Discontents, both published by Cam- bridge University Press. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he has appeared on television and radio, and he contributes regularly to popular media such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Playboy magazine. -

The Origin of Altruism

book reviews The origin of altruism Unto Others: The Evolution and about? I think the argument is largely seman- degree of relatedness. So we have a single Psychology of Unselfish Behavior tic, and could not be settled by observation. model, but two ways of analysing it. by Elliott Sober and David Sloan Wilson Two examples will make this clearer. More briefly, here is a second example. Harvard University Press: 1998. Pp. 394. First, consider Wilson’s ‘trait group’ Evolutionary game theory was first devel- $29.95, £19.95 model, first published in 1975 but still very oped to explain the ritualistic nature of ani- John Maynard Smith much part of his thinking. A population is mal fights. This had often been explained8 in divided into trait groups, and selection acts terms of the ‘good of the species’: it seemed It is obvious that the parts of organisms have upon them. The members then disperse and desirable to George Price and myself to specific functions. Since Darwin, this has mate randomly, and their offspring come attempt an explanation in terms of individ- been explained by natural selection, but together again in trait groups. There are two ual selection. Sober and Wilson reconsider what is the target of selection? Should indi- kinds of individual: altruists, who benefit (in this model. They come to exactly the same vidual organisms be thought of as the units terms of fitness) each of their fellow group conclusions that we reached, but argue that it of selection, or must one also consider levels members to a degree b, at a cost to themselves is a case of group selection. -

May 03 CI.Qxd

Philosophy of Chemistry by Eric Scerri Of course, the field of compu- hen I push my hand down onto my desk it tational quantum chemistry, does not generally pass through the which Dirac and other pioneers Wwooden surface. Why not? From the per- of quantum mechanics inadver- spective of physics perhaps it ought to, since we are tently started, has been increas- told that the atoms that make up all materials consist ingly fruitful in modern mostly of empty space. Here is a similar question that chemistry. But this activity has is put in a more sophisticated fashion. In modern certainly not replaced the kind of physics any body is described as a superposition of chemistry in which most practitioners are engaged. many wavefunctions, all of which stretch out to infin- Indeed, chemists far outnumber scientists in all other ity in principle. How is it then that the person I am fields of science. According to some indicators, such as talking to across my desk appears to be located in one the numbers of articles published per year, chemistry particular place? may even outnumber all the other fields of science put together. If there is any sense in which chemistry can The general answer to both such questions is that be said to have been reduced then it can equally be although the physics of microscopic objects essen- said to be in a high state of "oxidation" regarding cur- tially governs all of matter, one must also appeal to rent academic and industrial productivity. the laws of chemistry, material science, biology, and Starting in the early 1990s a group of philosophers other sciences. -

Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry

CALL FOR PAPERS First International Conference on Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry 25-27 June 2019 University of Paris Diderot, France Extended Deadline for Abstract Submission: 28 February 2019 The aim of this conference is to bring philosophers of biology and philosophers of chemistry together and to explore common grounds and topics of interest. We particularly welcome papers on (1) the philosophy of interdisciplinary fields between biology and chemistry; (2) historical case studies on the disciplinary divergence and convergence of biology and chemistry; and (3) the similarities and differences between philosophical approaches to biology and chemistry. Philosophy is broadly construed and includes epistemological, methodological, ontological, metaphysical, ethical, political, and legal issues of science. For a detailed description of possible topics, please see below and visit the conference website http://www.sphere.univ-paris-diderot.fr/spip.php?article2228&lang=en Instructions for Abstract Submission Submit a Word file including author name(s), affiliation, paper title, and an abstract of maximum 500 words by 28 February 2019 to Jean-Pierre Llored ([email protected]) . Registration If you are interested in participating, please register by sending an e-mail to Jean-Pierre Llored ([email protected]) before 30 April 2019. Venue Room 454A, Building Condorcet, University Paris Diderot, 4, rue Elsa Morante, 75013 Paris, France Sponsors CNRS; Laboratory SPHERE, Laboratory LIED, and Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Paris Diderot; Fondation de la Maison de la Chimie; Free University of Brussels; University of Lille Organizers Cécilia Bognon, Quentin Hiernaux, Jean-Pierre Llored, Joachim Schummer First international Conference on Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry 25-27 June 2019, University of Paris Diderot, France Description Background For much of the twentieth century, philosophy of science had almost exclusively been focused on physics and mathematics. -

DANIEL DENNETT and the SCIENCE of RELIGION Richard F

DANIEL DENNETT AND THE SCIENCE OF RELIGION Richard F. Green Department of Mathematics and Statistics University of Minnesota-Duluth Duluth, MN 55812 ABSTRACT Daniel Dennett (2006) recently published a book, “Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon,” which advocates the scientific study of religion. Dennett is a philosopher with wide-ranging interests including evolution and cognitive psychology. This talk is basically a review of Dennett’s religion book, but it will include comments about other work about religion, some mentioned by Dennett and some not. I will begin by describing my personal interest in religion and philosophy, including some recent reading. Then I will comment about the study of religion, including the scientific study of religion. Then I will describe some of Dennett’s ideas about religion. I will conclude by trying outlining the ideas that should be considered in order to understand religion. This talk is mostly about ideas, particularly religious beliefs, but not so much churches, creeds or religious practices. These other aspects of religion are important, and are the subject of study by a number of disciplines. I will mention some of the ways that people have studied religion, mainly to provide context for the particular ideas that I want to emphasize. I share Dennett’s reticence about defining religion. I will offer several definitions of religion, but religion is probably better defined by example than by attempting to specify its essence. A particular example of a religion is Christianity, even more particularly, Roman Catholicism. MOTIVATION My interest in philosophy and religion I. Beginnings I read a few books about religion and philosophy when I was in high school and imagined that college would be full of people arguing about religion and philosophy. -

Rethinking the Pragmatic Systems Biology and Systems-Theoretical Biology Divide: Toward a Complexity-Inspired Epistemology of Systems Biomedicine T

Medical Hypotheses 131 (2019) 109316 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Medical Hypotheses journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mehy Rethinking the pragmatic systems biology and systems-theoretical biology divide: Toward a complexity-inspired epistemology of systems biomedicine T Srdjan Kesić Department of Neurophysiology, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, University of Belgrade, Despot Stefan Blvd. 142, 11060 Belgrade, Serbia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This paper examines some methodological and epistemological issues underlying the ongoing “artificial” divide Systems biology between pragmatic-systems biology and systems-theoretical biology. The pragmatic systems view of biology has Cybernetics encountered problems and constraints on its explanatory power because pragmatic systems biologists still tend Second-order cybernetics to view systems as mere collections of parts, not as “emergent realities” produced by adaptive interactions Complexity between the constituting components. As such, they are incapable of characterizing the higher-level biological Complex biological systems phenomena adequately. The attempts of systems-theoretical biologists to explain these “emergent realities” Epistemology of complexity using mathematics also fail to produce satisfactory results. Given the increasing strategic importance of systems biology, both from theoretical and research perspectives, we suggest that additional epistemological and methodological insights into the possibility of further integration between -

Elliott Sober: Did Darwin Write the Origin Backwards?

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons Faculty Publications Department of Philosophy & Religious Studies 2011 Elliott obS er: Did Darwin Write the Origin Backwards? Philosophical Essays on Darwin’s Theory Charles H. Pence Louisiana State University, [email protected] Hope Hollocher University of Notre Dame Ryan Nichols California State University, Fullerton Grant Ramsey KU Leuven Edwin Siu Florida State University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/prs_pubs Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Recommended Citation Pence, Charles H.; Hollocher, Hope; Nichols, Ryan; Ramsey, Grant; Siu, Edwin; and Sportiello, Daniel John, "Elliott oS ber: Did Darwin Write the Origin Backwards? Philosophical Essays on Darwin’s Theory" (2011). Faculty Publications. 6. http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/prs_pubs/6 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Philosophy & Religious Studies at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Charles H. Pence, Hope Hollocher, Ryan Nichols, Grant Ramsey, Edwin Siu, and Daniel John Sportiello This book review is available at LSU Digital Commons: http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/prs_pubs/6 BOOK REVIEWS 705 lution of communication. After all, a full account of the evolution of language should include not just establishing signaling systems but also the origin (or invention) of the signals. This requires modifying the original game so that the players must first invent signals and then learn how to use them. -

Two Directions for Teleology: Naturalism and Idealism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Two directions for teleology: naturalism and idealism Published as: “Two directions for teleology: naturalism and idealism.” Synthese. DOI: 10.1007/s11229-017-1364-5. Please site published version. Andrew Cooper Department of Philosophy University of Durham 50 Old Elvet DH1 3HN, United Kingdom [email protected] Abstract: Philosophers of biology claim that function talk is consistent with naturalism. Yet recent work in biology places new pressure on this claim. An increasing number of biologists propose that the existence of functions depends on the organisation of systems. While systems are part of the domain studied by physics, they are capable of interacting with this domain through organising principles. This is to say that a full account of biological function requires teleology. Does naturalism preclude reference to teleological causes? Or are organised systems precisely a naturalised form of teleology? In this paper I suggest that the biology of organised systems reveals several contradictions in the main philosophical conceptions of naturalism. To integrate organised systems with naturalism’s basic assumptions—that there is no theory-independent view for metaphysics, and that nature is intelligible—I propose an idealist solution. Keywords: naturalism, evolutionary biology, function, idealism, Kant Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Markus Gabriel, Andy Jones, Tim Smartt, Paul Redding, and Yarran Hominh for their insightful discussion and invaluable feedback on early drafts of this paper. I would also like to thank my anonymous reviewers for their detailed and stimulating comments, which helped improve this paper immensely.