Recent Work in the Philosophy of Biology, Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Kinds and Concepts: a Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account

Natural Kinds and Concepts: A Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account Ingo Brigandt Abstract: In this chapter I lay out a notion of philosophical naturalism that aligns with prag- matism. It is developed and illustrated by a presentation of my views on natural kinds and my theory of concepts. Both accounts reflect a methodological naturalism and are defended not by way of metaphysical considerations, but in terms of their philosophical fruitfulness. A core theme is that the epistemic interests of scientists have to be taken into account by any natural- istic philosophy of science in general, and any account of natural kinds and scientific concepts in particular. I conclude with general methodological remarks on how to develop and defend philosophical notions without using intuitions. The central aim of this essay is to put forward a notion of naturalism that broadly aligns with pragmatism. I do so by outlining my views on natural kinds and my account of concepts, which I have defended in recent publications (Brigandt, 2009, 2010b). Philosophical accounts of both natural kinds and con- cepts are usually taken to be metaphysical endeavours, which attempt to develop a theory of the nature of natural kinds (as objectively existing entities of the world) or of the nature of concepts (as objectively existing mental entities). However, I shall argue that any account of natural kinds or concepts must an- swer to epistemological questions as well and will offer a simultaneously prag- matist and naturalistic defence of my views on natural kinds and concepts. Many philosophers conceive of naturalism as a primarily metaphysical doc- trine, such as a commitment to a physicalist ontology or the idea that humans and their intellectual and moral capacities are a part of nature. -

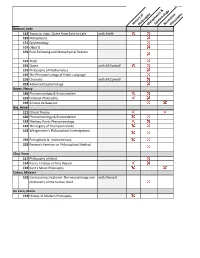

History of Philosophymetaphysics & Epistem Ology Norm Ative

HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Azzouni, Jody 114 Topics in Logic: Quine from Early to Late with Smith 120 Metaphysics 131 Epistemology 191 Objects 191 Rule-Following and Metaphysical Realism 191 Truth 191 Quine with McConnell 191 Philosophy of Mathematics 192 The Phenomenology of Public Language 195 Chomsky with McConnell 292 Advanced Epistemology Bauer, Nancy 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 191 Feminist Philosophy 192 Simone de Beauvoir Baz, Avner 121 Ethical Theory 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 192 Merleau Ponty Phenomenology 192 The Legacy of Thompson Clarke 192 Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations 292 Perceptions & Indeterminacy 292 Research Seminar on Philosophical Method Choi, Yoon 117 Philosophy of Mind 164 Kant's Critique of Pure Reason 192 Kant's Moral Philosophy Cohen, Michael 192 Conciousness Explored: The neurobiology and with Dennett philosophy of the human mind De Caro, Mario 152 History of Modern Philosophy De HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Car 191 Nature & Norms 191 Free Will & Moral Responsibility Denby, David 133 Philosophy of Language 152 History of Modern Philosophy 191 History of Analytic Philosophy 191 Topics in Metaphysics 195 The Philosophy of David Lewis Dennett, Dan 191 Foundations of Cognitive Science 192 Artificial Agents & Autonomy with Scheutz 192 Cultural Evolution-Is it Darwinian 192 Topics in Philosophy of Biology: The Boundaries with Forber of Darwinian Theory 192 Evolving Minds: From Bacteria to Bach 192 Conciousness -

Hodin2013 Ch19.Pdf

736 Part 4 The History of Life How are developmental biology and evolution related? Developmental biol- ogy is the study of the processes by which an organism grows from zygote to reproductive adult. Evolutionary biology is the study of changes in populations across generations. As with non-shattering cereals, evolutionary changes in form and function are rooted in corresponding changes in development. While evo- lutionary biologists are concerned with why such changes occur, developmental biology tells us how these changes happen. Darwin recognized that for a com- plete understanding of evolution, one needs to take account of both the “why” and the “how,” and hence, of the “important subject” of developmental biology. In Darwin’s day, studies of development went hand in hand with evolution, as when Alexander Kowalevsky (1866) first described the larval stage of the sea squirt as having clear chordate affinities, something that is far less clear when examining their adults. Darwin himself (1851a,b; 1854a,b) undertook extensive studies of barnacles, inspired in part by Burmeister’s description (1834) of their larval and metamorphic stages as allying them with the arthropods rather than the mollusks. If the intimate connection between development and evolution was so clear to Darwin and others 150 years ago, why is evolutionary developmental biology (or evo-devo) even considered a separate subject, and not completely inte- grated into the study of evolution? The answer seems to be historical. Although Darwin recognized the importance of development in understanding evolution, development was largely ignored by the architects of the 20th-century codifica- tion of evolutionary biology known as the modern evolutionary synthesis. -

The University of Chicago Epistasis, Contingency, And

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO EPISTASIS, CONTINGENCY, AND EVOLVABILITY IN THE SEQUENCE SPACE OF ANCIENT PROTEINS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES AND THE PRITZKER SCHOOL OF MEDICINE IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN BIOCHEMISTRY AND MOLECULAR BIOPHYSICS BY TYLER NELSON STARR CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2018 Table of Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... vii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. ix Chapter 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................1 1.1 Sequence space and protein evolution .............................................................1 1.2 Deep mutational scanning ................................................................................2 1.3 Epistasis ...........................................................................................................3 1.4 Chance and determinism ..................................................................................4 1.5 Evolvability ......................................................................................................6 -

What Can We Learn from Fitness Landscapes?

What can we learn from fitness landscapes? The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hartl, Daniel L. 2014. “What Can We Learn from Fitness Landscapes?” Current Opinion in Microbiology 21 (October): 51–57. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2014.08.001. Published Version 10.1016/j.mib.2014.08.001 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:22898356 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for Current Opinion in Microbiology Manuscript Draft Manuscript Number: Title: What Can We Learn From Fitness Landscapes? Article Type: 22 Growth&Develop: prokaryotes (2014 Corresponding Author: Dr. Daniel Hartl, Corresponding Author's Institution: First Author: Daniel Hartl Order of Authors: Daniel Hartl Manuscript Click here to view linked References What Can We Learn From Fitness Landscapes? Daniel L. Hartl Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA Contact information: Email: [email protected], TEL: 617-396-3917 In evolutionary biology, the fitness landscape of set of mutants is the mapping of genotypes onto phenotypes when the phenotype is fitness or some proxy for fitness such as growth rate or drug resistance. When the set of mutants is not too large, it is possible to create every possible combination of mutants and map these to fitness. -

Molecular Homology and Multiple-Sequence Alignment: an Analysis of Concepts and Practice

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Systematic Botany, 2015, 28,46–62 LAS Johnson Review http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/SB15001 Molecular homology and multiple-sequence alignment: an analysis of concepts and practice David A. Morrison A,D, Matthew J. Morgan B and Scot A. Kelchner C ASystematic Biology, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 18D, Uppsala 75236, Sweden. BCSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. CDepartment of Biology, Utah State University, 5305 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT 84322-5305, USA. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Sequence alignment is just as much a part of phylogenetics as is tree building, although it is often viewed solely as a necessary tool to construct trees. However, alignment for the purpose of phylogenetic inference is primarily about homology, as it is the procedure that expresses homology relationships among the characters, rather than the historical relationships of the taxa. Molecular homology is rather vaguely defined and understood, despite its importance in the molecular age. Indeed, homology has rarely been evaluated with respect to nucleotide sequence alignments, in spite of the fact that nucleotides are the only data that directly represent genotype. All other molecular data represent phenotype, just as do morphology and anatomy. Thus, efforts to improve sequence alignment for phylogenetic purposes should involve a more refined use of the homology concept at a molecular level. To this end, we present examples of molecular-data levels at which homology might be considered, and arrange them in a hierarchy. The concept that we propose has many levels, which link directly to the developmental and morphological components of homology. -

Phenotypic Landscape Inference Reveals Multiple Evolutionary Paths to C4 Photosynthesis

RESEARCH ARTICLE elife.elifesciences.org Phenotypic landscape inference reveals multiple evolutionary paths to C4 photosynthesis Ben P Williams1†, Iain G Johnston2†, Sarah Covshoff1, Julian M Hibberd1* 1Department of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom; 2Department of Mathematics, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom Abstract C4 photosynthesis has independently evolved from the ancestral C3 pathway in at least 60 plant lineages, but, as with other complex traits, how it evolved is unclear. Here we show that the polyphyletic appearance of C4 photosynthesis is associated with diverse and flexible evolutionary paths that group into four major trajectories. We conducted a meta-analysis of 18 lineages containing species that use C3, C4, or intermediate C3–C4 forms of photosynthesis to parameterise a 16-dimensional phenotypic landscape. We then developed and experimentally verified a novel Bayesian approach based on a hidden Markov model that predicts how the C4 phenotype evolved. The alternative evolutionary histories underlying the appearance of C4 photosynthesis were determined by ancestral lineage and initial phenotypic alterations unrelated to photosynthesis. We conclude that the order of C4 trait acquisition is flexible and driven by non-photosynthetic drivers. This flexibility will have facilitated the convergent evolution of this complex trait. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.00961.001 Introduction *For correspondence: Julian. The convergent evolution of complex traits is surprisingly common, with examples including camera- [email protected] like eyes of cephalopods, vertebrates, and cnidaria (Kozmik et al., 2008), mimicry in invertebrates and †These authors contributed vertebrates (Santos et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2012) and the different photosynthetic machineries of equally to this work plants (Sage et al., 2011a). -

Molecular Homology and Multiple-Sequence Alignment: an Analysis of Concepts and Practice

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Systematic Botany, 2015, 28, 46–62 LAS Johnson Review http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/SB15001 Molecular homology and multiple-sequence alignment: an analysis of concepts and practice David A. Morrison A,D, Matthew J. Morgan B and Scot A. Kelchner C ASystematic Biology, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 18D, Uppsala 75236, Sweden. BCSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. CDepartment of Biology, Utah State University, 5305 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT 84322-5305, USA. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Sequence alignment is just as much a part of phylogenetics as is tree building, although it is often viewed solely as a necessary tool to construct trees. However, alignment for the purpose of phylogenetic inference is primarily about homology, as it is the procedure that expresses homology relationships among the characters, rather than the historical relationships of the taxa. Molecular homology is rather vaguely defined and understood, despite its importance in the molecular age. Indeed, homology has rarely been evaluated with respect to nucleotide sequence alignments, in spite of the fact that nucleotides are the only data that directly represent genotype. All other molecular data represent phenotype, just as do morphology and anatomy. Thus, efforts to improve sequence alignment for phylogenetic purposes should involve a more refined use of the homology concept at a molecular level. To this end, we present examples of molecular-data levels at which homology might be considered, and arrange them in a hierarchy. The concept that we propose has many levels, which link directly to the developmental and morphological components of homology. -

Homology of Process: Developmental Dynamics in Comparative Biology

Forthcoming in Interface Focus Homology of process: developmental dynamics in comparative biology James DiFrisco1,* and Johannes Jaeger2,3 (1) Institute of Philosophy, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium (2) Complexity Science Hub (CSH) Vienna, Josefstädter Straße 39, 1080 Vienna, Austria (3) Department of Molecular Evolution & Development, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Abstract: Comparative biology builds up systematic knowledge of the diversity of life, across evolutionary lineages and levels of organization, starting with evidence from a sparse sample of model organisms. In developmental biology, a key obstacle to the growth of comparative approaches is that the concept of homology is not very well defined for levels of organization that are intermediate between individual genes and morphological characters. In this paper, we investigate what it means for ontogenetic processes to be homologous, focusing specifically on the examples of insect segmentation and vertebrate somitogenesis. These processes can be homologous without homology of the underlying genes or gene networks, since the latter can diverge over evolutionary time, while the dynamics of the process remain the same. Ontogenetic processes like these therefore constitute a dissociable level and distinctive unit of comparison requiring their own specific criteria of homology. In addition, such processes are typically complex and nonlinear, such that their rigorous description and comparison not only requires observation and experimentation, but also dynamical modeling. We propose six criteria of process homology, combining recognized indicators (sameness of parts, morphological outcome, and topological position) with novel ones derived from dynamical systems modeling (sameness of dynamical properties, dynamical complexity, and evidence for transitional forms). We show how these criteria apply to animal segmentation and other ontogenetic processes. -

Molecular Homology & the Ancient Genetic Toolkit: How Evolutionary

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2019 Molecular Homology & the Ancient Genetic Toolkit: How Evolutionary Development Could Shape Your Next Doctor's Appointment Elizabeth G. Plender Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Cell Biology Commons, Developmental Biology Commons, Evolution Commons, Molecular Biology Commons, and the Molecular Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Plender, Elizabeth G., "Molecular Homology & the Ancient Genetic Toolkit: How Evolutionary Development Could Shape Your Next Doctor's Appointment" (2019). All Regis University Theses. 905. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/905 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOLECULAR HOMOLOGY AND THE ANCIENT GENETIC TOOLKIT: HOW EVOLUTIONARY DEVELOPMENT COULD SHAPE YOUR NEXT DOCTOR’S APPOINTMENT A thesis submitted to Regis College The Honors Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements For Graduation with Honors By Elizabeth G. Plender May 2019 Thesis written by Elizabeth Plender Approved by Thesis Advisor Thesis Reader Accepted by Director, University Honors Program ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... -

Quantifying the Fitness of Tissue-Specific Evolutionary

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/401059; this version posted August 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Quantifying the fitness of tissue- specific evolutionary trajectories by harnessing cancer’s repeatability at the genetic level Tokutomi N1, Moyret-Lalle C2, Puisieux A2, Sugano S1, Martinez P2. 1 Department of Computational Biology and Medical Sciences, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 108-8639, Japan. 2 Univ Lyon, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, INSERM 1052, CNRS 5286, Centre Léon Bérard, Cancer Research Center of Lyon, Lyon, 69008, France, INSERM U1052, Cancer Research Center of Lyon, Lyon, F-69008, France. Correspondence to Pierre Martinez: [email protected] Abstract Cancer is a potentially lethal disease, in which patients with nearly identical genetic backgrounds can develop a similar pathology through distinct combinations of genetic alterations. We aimed to reconstruct the evolutionary process underlying tumour initiation, using the combination of convergence and discrepancies observed across 2,742 cancer genomes from 9 tumour types. We developed a framework using the repeatability of cancer development to score the fitness of genetic clones, as their potential to malignantly progress and invade their environment of origin. Using this framework, we found that pre-malignant skin and colorectal lesions appeared specifically adapted to their local environment, yet insufficiently for full cancerous transformation. We found that metastatic clones were more adapted to the site of origin than to the invaded tissue, suggesting that genetics may be more important for local progression than for the invasion of distant organs. -

The Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85128-2 - The Cambridge Companion to the Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L. Hull and Michael Ruse Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to THE PHILOSOPHY OF BIOLOGY The philosophy of biology is one of the most exciting new areas in the field of philosophy and one that is attracting much attention from working scientists. This Companion, edited by two of the founders of the field, includes newly commissioned essays by senior scholars and by up-and- coming younger scholars who collectively examine the main areas of the subject – the nature of evolutionary theory, classification, teleology and function, ecology, and the prob- lematic relationship between biology and religion, among other topics. Up-to-date and comprehensive in its coverage, this unique volume will be of interest not only to professional philosophers but also to students in the humanities and researchers in the life sciences and related areas of inquiry. David L. Hull is an emeritus professor of philosophy at Northwestern University. The author of numerous books and articles on topics in systematics, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology, and naturalized epistemology, he is a recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Michael Ruse is professor of philosophy at Florida State University. He is the author of many books on evolutionary biology, including Can a Darwinian Be a Christian? and Darwinism and Its Discontents, both published by Cam- bridge University Press. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he has appeared on television and radio, and he contributes regularly to popular media such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Playboy magazine.