Meyer, Stephen C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Intelligent Design Creationist Movement: Its True Nature and Goals

UNDERSTANDING THE INTELLIGENT DESIGN CREATIONIST MOVEMENT: ITS TRUE NATURE AND GOALS A POSITION PAPER FROM THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY OFFICE OF PUBLIC POLICY AUTHOR: BARBARA FORREST, Ph.D. Reviewing Committee: Paul Kurtz, Ph.D.; Austin Dacey, Ph.D.; Stuart D. Jordan, Ph.D.; Ronald A. Lindsay, J. D., Ph.D.; John Shook, Ph.D.; Toni Van Pelt DATED: MAY 2007 ( AMENDED JULY 2007) Copyright © 2007 Center for Inquiry, Inc. Permission is granted for this material to be shared for noncommercial, educational purposes, provided that this notice appears on the reproduced materials, the full authoritative version is retained, and copies are not altered. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires written permission from the Center for Inquiry, Inc. Table of Contents Section I. Introduction: What is at stake in the dispute over intelligent design?.................. 1 Section II. What is the intelligent design creationist movement? ........................................ 2 Section III. The historical and legal background of intelligent design creationism ................ 6 Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) ............................................................................ 6 McLean v. Arkansas (1982) .............................................................................. 6 Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) ............................................................................. 7 Section IV. The ID movement’s aims and strategy .............................................................. 9 The “Wedge Strategy” ..................................................................................... -

Intelligent Design, Abiogenesis, and Learning from History: Dennis R

Author Exchange Intelligent Design, Abiogenesis, and Learning from History: Dennis R. Venema A Reply to Meyer Dennis R. Venema Weizsäcker’s book The World View of Physics is still keeping me very busy. It has again brought home to me quite clearly how wrong it is to use God as a stop-gap for the incompleteness of our knowledge. If in fact the frontiers of knowledge are being pushed back (and that is bound to be the case), then God is being pushed back with them, and is therefore continually in retreat. We are to find God in what we know, not in what we don’t know; God wants us to realize his presence, not in unsolved problems but in those that are solved. Dietrich Bonhoeffer1 am thankful for this opportunity to nature, is the result of intelligence. More- reply to Stephen Meyer’s criticisms over, this assertion is proffered as the I 2 of my review of his book Signature logical basis for inferring design for the in the Cell (hereafter Signature). Meyer’s origin of biological information: if infor- critiques of my review fall into two gen- mation only ever arises from intelli- eral categories. First, he claims I mistook gence, then the mere presence of Signature for an argument against bio- information demonstrates design. A few logical evolution, rendering several of examples from Signature make the point my arguments superfluous. Secondly, easily: Meyer asserts that I have failed to refute … historical scientists can show that his thesis by not providing a “causally a presently acting cause must have adequate alternative explanation” for the been present in the past because the origin of life in that the few relevant cri- proposed candidate is the only known tiques I do provide are “deeply flawed.” cause of the effect in question. -

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Spontaneous Generation of Life Is the Inevitable Outcome of Time, Chance, and the Right Chemical Conditions

“The origin of life appears almost a miracle, so many are the conditions which would have had to be satisfied to get it going.” –Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the DNA double helix structure1 Introduction According to evolutionary theory, all life – bacteria, plants, and people – evolved from a hypothetical first cell, which allegedly arose spontaneously from chemical substrates. This is said to have happened over 3 billion years ago. That hypothetical first cell has been called LUCA (last universal common ancestor). This first cell is assumed to be at the very base of Darwin’s hypothetical “tree of life”. It is almost universally claimed that life came from non-life (abiogenesis). Is this good science? It is almost universally claimed that spontaneous generation of life is the inevitable outcome of time, chance, and the right chemical conditions. Is this claim even remotely credible? School curricula, textbooks, educational science programs, and countless museums consistently insist there is a strong scientific case for the spontaneous origin of life. From a naturalistic evolutionary perspective, it should not be surprising that spontaneous generation is assumed to be feasible, as it is essential to the evolutionary story. We can’t have Darwin’s “tree of life” without the trunk, which emerged from the primordial seed of that first cell. We are continuously told stories that sound like plausible scenarios for how simple inorganic molecules might have come together to give rise to the first living cell. However, upon careful examination, we find that the stories being told are not only extremely speculative – they are rationally indefensible. -

Ono Mato Pee 145

789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 9 789493 148215 789493 9 9 789493 148215 9 148215 789493 148215 789493 9 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 789493 9 789493 148215 9 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 145 PEE MATO ONO Graphic Design Systems, and the Systems of Graphic Design Francisco Laranjo Bibliography M.; Drenttel, W. & Heller, S. (2012) Within graphic design, the concept of systems is profoundly Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for Looking Closer 4: Critical Writings rooted in form. When a term such as system is invoked, it is the Pluriverse (New Ecologies for on Graphic Design. Allworth Press, normally related to macro and micro-typography, involving pp. 199–207. the Twenty-First Century). Duke book design and typesetting, but also addressing type design University Press. Manzini, E. (2015) Design, When or parametric typefaces. Branding and signage are two other Jenner, K. (2016) Chill Kendall Jenner Everybody Designs: An Introduction Didn’t Think People Would Care to Design for Social Innovation. domains which nearly claim exclusivity of the use of the That She Deleted Her Instagram. Massachusetts: MIT Press. word ‘systems’ in relation to graphic design. A key example of In: Vogue. Available at: https://www. Meadows, D. (2008) Thinking in this is the influential bookGrid Systems in Graphic Design vogue.com/article/kendall-jenner- Systems. -

Arguments from Design

Arguments from Design: A Self-defeating Strategy? Victoria S. Harrison University of Glasgow This is an archived version of ‘Arguments form Design: A Self-defeating Strategy?’, published in Philosophia 33 (2005): 297–317. Dr V. Harrison Department of Philosophy 69 Oakfield Avenue University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8LT Scotland UK E-mail: [email protected] Arguments from Design: A Self-defeating Strategy? Abstract: In this article, after reviewing traditional arguments from design, I consider some more recent versions: the so-called ‘new design arguments’ for the existence of God. These arguments enjoy an apparent advantage over the traditional arguments from design by avoiding some of Hume’s famous criticisms. However, in seeking to render religion and science compatible, it seems that they require a modification not only of our scientific understanding but also of the traditional conception of God. Moreover, there is a key problem with arguments from design that Mill raised to which the new arguments seem no less vulnerable than the older versions. The view that science and religion are complementary has at least one significant advantage over other positions, such as the view that they are in an antagonistic relationship or the view that they are so incommensurable that they are neither complementary nor antagonistic. The advantage is that it aspires to provide a unified worldview that is sensitive to the claims of both science and religion. And surely, such a worldview, if available, would seem to be superior to one in which, say, scientific and religious claims were held despite their obvious contradictions. -

And Then God Created Kansas--The Evolution/Creationism Debate In

COMMENTS AND THEN GOD CREATED KANSAS? THE EVOLUTION/CREATIONISM DEBATE IN AMERICA'S PUBLIC SCHOOLS MARJORIE GEORGE' "For most Kansans, there really is no conflict between science and religion. Our churches have helped us search for spiritual truth, and our schools have helped us understand the natural world." -Brad Williamson, biology teacher at Olathe East High School in Olathe, Kansas.' INTRODUCTION Kansas has recently become embroiled in a fierce debate over the minds of the state's children, specifically regarding what those children will learn in their public school science classrooms. At first glance, a science curriculum does not seem like a subject of great controversy, but it continues to be one in Kansas and other communities across the country. The controversy hinges specifically on the role evolution should play in science classrooms, but also reflects the broader debate over what role schools should play in students' moral development. Today many parents are worried about sending their children to t BA. 1993, Washington University; J.D. Candidate 2001, University of Pennsylania. Thank you to Sarah Barringer Gordon for her initial advice and editorial comments, and Tracey George for her always helpful comments, as well as her thirty years of encouragement and inspiration. A very special thanks to Jonathan Petty tor alwa)s believing in me and providing unwavering support for my decision to attend law school and of my numerous pursuits during law school. Finally, thank you to all of the Penn Law Review editors for their hard work on this and every article. I Brad Williamson, I Teach, Therefore I IVor7, in Kansas, WASH. -

Mike Kelley's Studio

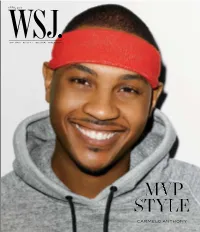

No PMS Flood Varnish Spine: 3/16” (.1875”) 0413_WSJ_Cover_02.indd 1 2/4/13 1:31 PM Reine de Naples Collection in every woman is a queen BREGUET BOUTIQUES – NEW YORK FIFTH AVENUE 646 692-6469 – NEW YORK MADISON AVENUE 212 288-4014 BEVERLY HILLS 310 860-9911 – BAL HARBOUR 305 866-1061 – LAS VEGAS 702 733-7435 – TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 – WWW.BREGUET.COM QUEEN1-WSJ_501x292.indd 1-2 01.02.13 16:56 BREGUET_205640303.indd 2 2/1/13 1:05 PM BREGUET_205640303.indd 3 2/1/13 1:06 PM a sporting life! 1-800-441-4488 Hermes.com 03_501,6x292,1_WSJMag_Avril_US.indd 1 04/02/13 16:00 FOR PRIVATE APPOINTMENTS AND MADE TO MEASURE INQUIRIES: 888.475.7674 R ALPHLAUREN.COM NEW YORK BEVERLY HILLS DALLAS CHICAGO PALM BEACH BAL HARBOUR WASHINGTON, DC BOSTON 1.855.44.ZEGNA | Shop at zegna.com Passion for Details Available at Macy’s and macys.com the new intense fragrance visit Armanibeauty.com SHIONS INC. Phone +1 212 940 0600 FA BOSS 0510/S HUGO BOSS shop online hugoboss.com www.omegawatches.com We imagined an 18K red gold diving scale so perfectly bonded with a ceramic watch bezel that it would be absolutely smooth to the touch. And then we created it. The result is as aesthetically pleasing as it is innovative. You would expect nothing less from OMEGA. Discover more about Ceragold technology on www.omegawatches.com/ceragold New York · London · Paris · Zurich · Geneva · Munich · Rome · Moscow · Beijing · Shanghai · Hong Kong · Tokyo · Singapore 26 Editor’s LEttEr 28 MasthEad 30 Contributors 32 on thE CovEr slam dunk Fashion is another way Carmelo Anthony is scoring this season. -

Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It?

Leaven Volume 17 Issue 2 Theology and Science Article 6 1-1-2009 Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? Chris Doran [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Doran, Chris (2009) "Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It?," Leaven: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol17/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Doran: Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? CHRIS DORAN imaginethatwe have all had occasion to look up into the sky on a clear night, gaze at the countless stars, and think about how small we are in comparison to the enormity of the universe. For everyone except Ithe most strident atheist (although I suspect that even s/he has at one point considered the same feeling), staring into space can be a stark reminder that the universe is much grander than we could ever imagine, which may cause us to contemplate who or what might have put this universe together. For believers, looking up at tJotestars often puts us into the same spirit of worship that must have filled the psalmist when he wrote, "The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands" (Psalms 19.1). -

Intelligent Design Is Not Science” Given by John G

An Outline of a lecture entitled, “Intelligent Design is not Science” given by John G. Wise in the Spring Semester of 2007: Slide 1 Why… … do humans have so much trouble with wisdom teeth? … is childbirth so dangerous and painful? Because a big, thinking brain is an advantage, and evolution is imperfect. Slide 2 Charles Darwin’s Revolutionary Idea His book changed the world. All life forms on this planet are related to each other through “Descent with modification over generations from a common ancestor”. Natural processes fully explain the biological connections between all life on the planet. Slide 3 Darwin’s Idea is Dangerous (from the book of the same title by Daniel Dennett) If we have evolution, we no longer need a Creator to create each and every species. Darwinism is dangerous because it infers that God did not directly and purposefully create us. It simply states that we evolved. Slide 4 Intelligent Design Attempts to Counter Darwin “Intelligent Design” has been proposed as way out of this dilemma. – Phillip Johnson, William Dembski, and Michael Behe (to name a few). They attempt to redefine science to encompass the supernatural as well as the natural world. They accept Darwin’s evolution, if an Intelligent Designer is (sometimes) substituted for natural selection. Design arguments are not new: − 1250 - St. Thomas Aquinas - first design argument − 1802 - Natural Theology - William Paley – perhaps the best(?) design argument Slide 5 What is Science? A specific way of understanding the natural world. Based on the idea that our senses give us accurate information about the Universe. -

Constraint Closure Drove Major Transitions in the Origins of Life

entropy Article Constraint Closure Drove Major Transitions in the Origins of Life Niles E. Lehman 1 and Stuart. A. Kauffman 2,* 1 Edac Research, 1879 Camino Cruz Blanca, Santa Fe, NM 87505, USA; [email protected] 2 Institute for Systems Biology, Seattle, WA 98109, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Life is an epiphenomenon for which origins are of tremendous interest to explain. We provide a framework for doing so based on the thermodynamic concept of work cycles. These cycles can create their own closure events, and thereby provide a mechanism for engendering novelty. We note that three significant such events led to life as we know it on Earth: (1) the advent of collective autocatalytic sets (CASs) of small molecules; (2) the advent of CASs of reproducing informational polymers; and (3) the advent of CASs of polymerase replicases. Each step could occur only when the boundary conditions of the system fostered constraints that fundamentally changed the phase space. With the realization that these successive events are required for innovative forms of life, we may now be able to focus more clearly on the question of life’s abundance in the universe. Keywords: origins of life; constraint closure; RNA world; novelty; autocatalytic sets 1. Introduction The plausibility of life in the universe is a hotly debated topic. As of today, life is only known to exist on Earth. Thus, it may have been a singular event, an infrequent event, or a common event, albeit one that has thus far evaded our detection outside our own planet. Herein, we will not attempt to argue for any particular frequency of life. -

Basic Concepts of Chemical Bonding

Basic Concepts of Chemical Bonding Cover 8.1 to 8.7 EXCEPT 1. Omit Energetics of Ionic Bond Formation Omit Born-Haber Cycle 2. Omit Dipole Moments ELEMENTS & COMPOUNDS • Why do elements react to form compounds ? • What are the forces that hold atoms together in molecules ? and ions in ionic compounds ? Electron configuration predict reactivity Element Electron configurations Mg (12e) 1S 2 2S 2 2P 6 3S 2 Reactive Mg 2+ (10e) [Ne] Stable Cl(17e) 1S 2 2S 2 2P 6 3S 2 3P 5 Reactive Cl - (18e) [Ar] Stable CHEMICAL BONDSBONDS attractive force holding atoms together Single Bond : involves an electron pair e.g. H 2 Double Bond : involves two electron pairs e.g. O 2 Triple Bond : involves three electron pairs e.g. N 2 TYPES OF CHEMICAL BONDSBONDS Ionic Polar Covalent Two Extremes Covalent The Two Extremes IONIC BOND results from the transfer of electrons from a metal to a nonmetal. COVALENT BOND results from the sharing of electrons between the atoms. Usually found between nonmetals. The POLAR COVALENT bond is In-between • the IONIC BOND [ transfer of electrons ] and • the COVALENT BOND [ shared electrons] The pair of electrons in a polar covalent bond are not shared equally . DISCRIPTION OF ELECTRONS 1. How Many Electrons ? 2. Electron Configuration 3. Orbital Diagram 4. Quantum Numbers 5. LEWISLEWIS SYMBOLSSYMBOLS LEWISLEWIS SYMBOLSSYMBOLS 1. Electrons are represented as DOTS 2. Only VALENCE electrons are used Atomic Hydrogen is H • Atomic Lithium is Li • Atomic Sodium is Na • All of Group 1 has only one dot The Octet Rule Atoms gain, lose, or share electrons until they are surrounded by 8 valence electrons (s2 p6 ) All noble gases [EXCEPT HE] have s2 p6 configuration.