The Persistence of Parody in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Lyric Opera Brings 'The Lighthouse'

Boston Lyric Opera brings ‘The Lighthouse’ to JFK By Harlow Robinson | GLOBE CORRESPONDENT JONATHAN WIGGS/GLOBE STAFF Thomas Hase, lighting designer for ‘‘The Lighthouse,’’ at the JFK Library. In New England we love our lighthouses. Beacons of safety in the stormy dark, they adorn the jagged coastline like timeless monuments to our maritime history. But lighthouses, especially in the pre- automation era, also gave rise to more unsettling feelings and questions. Who lives there, anyhow? What weird phenomena might lighthouse keepers witness, or imagine, during those long days and nights of lonely vigil, fog, and spray? These questions also fascinated distinguished British composer Peter Maxwell Davies. For many years, Davies, 77, has lived on Sanday, one of the remote Orkney Islands north of Scotland, where lighthouses are crucial fixtures of the ruggedly romantic landscape. In 1979, Davies transformed his interest in local maritime lore into music when he completed “The Lighthouse,’’ a chamber opera in a prologue and one act. Since its 1980 premiere at the Edinburgh Festival, “The Lighthouse’’ has become one of the most popular of all 20th-century operas, having been performed by more than 100 different companies. This week, Boston Lyric Opera will present four performances in Smith Hall at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. British stage director Tim Albery will make his BLO debut, as will set and costume designer Camellia Koo. BLO’s British-born music director David Angus will conduct. “The Lighthouse’’ is the latest offering in BLO’s Opera Annex program, created to stage productions in alternative, non-theatrical venues around the city. -

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

SIR PETER MAXWELL DAVIES: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1955: “Burchiello” for sixteen percussion instruments “Opus Clavicembalisticum(Sorabji)” for orchestra “Work on a Theme by Thomas Tompkins” for orchestra 1957: St. Michael”-Sonata for seventeen wind instruments, op.6: 17 minutes 1958: “Prolation” for orchestra, op.8: 20 minutes 1959: “Five Canons” for school/amateur orchestra “Pavan and Galliard” for school/amateur orchestra “Variations on a Theme for Chords” for school/amateur orchestra 1959/76: Five Klee Pictures for orchestra, op.12: 10 minutes + (Collins cd) 1960: Three Pieces for junior orchestra 1961: Fantasy on the National Anthem for school/amateur orchestra 1962: First Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op.19: 11 minutes Sinfonia for chamber orchestra, op. 20: 23 minutes + Regis d) 1963: “Veni Sancte Spiritus” for soprano, contralto, tenor, baritone, chorus and orchestra, op.22: 20 minutes 1964: Second Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op. 23: 39 minutes + (Decca cd) 1967: Songs to Words by Dante for baritone and small orchestra 1969: Foxtrot “St. Thomas Wake” for orchestra, op.37: 20 minutes + (Naxos cd) Motet “Worldes Bliss” for orchestra, op.38: 37 minutes 1971: Suite from “The Boyfriend” for small orchestra, op.50b: 26 minutes * + (Collins cd) 1972: “Walton Tribute” for orchestra Masque “Blind Man’s Buff” for soprano or treble, mezzo-soprano, mime and small orchestra, op.51: 20 minutes 1973: “Stone Liturgy-Runes from a House of the Dead” for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

Frank Rosolino

FRANK ROSOLINO s far as really being here, weeks has been a complete ball. have. Those I've met and heard in- this was my first visit to Also, on a few nights John Taylor clude John Marshall, Wally Smith, Britain. I was here in 1953 was committed elsewhere; so Bobby Lamb, Don Lusher, George Awith Stan Kenton, which Gordon Beck come in to take his Chisholm. I liked George's playing was just an overnight thing; so place. He's another really excellent very much; he has a nice conception twenty years have elapsed in be- player. You've got some great play- and feel, good soul, and he plays tween. I've been having an abso- ers round here! with an extremely good melodic lutely beautiful time here, and en- They're equal to musicians I sense. joying London. work with in the States. I mean, it As for my beginnings—I was Playing at Ronnie Scott's with doesn't matter where you are; once born and raised in Detroit, Michigan, me I had John Taylor on piano, Ron you've captured the feeling for jazz, until I was old enough to be drafted Mathewson on bass and Martin and you've been playing it practi- into the Service, which was the latter Drew on drums. Absolutely great cally all your life, you're a pro at it. part of '44. I started playing guitar players, every one of 'em. I can't tell I've heard so much about when I was nine or ten. My father you how much I enjoyed myself, and trombonist Chris Pyne that when I played parties and weddings on it just came out that way. -

Peter Maxwell Davies Eigentliche Grund Dafür Klar: Ich Wollte Keinen Dicken Deutsche Fassung: Cris Posslac

557400 bk Max 14/7/08 10:53 Page 4 diszipliniert, wobei, wie ich glaube, durch die recht schwarzen Schluss-Strich ziehen, wollte nicht, dass das genaue und komplexe Arbeit mit magischen Quadraten ein letztes Quartett sein soll. Ich musste die Tür offen einige Ordnung entstanden ist. lassen: Mir hat die Arbeit an den Naxos-Quartetten so PETER Ich habe auch auf das dritte Naxos Quartet viel Freude gemacht (und ich habe dabei vielleicht sogar verwiesen. Dort habe ich dem Violoncello einen Vers das eine oder andere gelernt), dass theoretisch daraus von Michelangelo unterlegt, der mit den Worten noch mehr entstehen könnte. MAXWELL DAVIES beginnt: Caro me il sonno, e più l’esser di sasso („Der Eine weitere Versuchung bestand darin, in einer Schlaf ist mir teuer, und von Stein zu sein, ist teurer“). feierlichen Abschiedssequenz auf jedes der vorigen In diesem Gedicht beklagt der Dichter, dass er im Quartette anzuspielen, wie ich das im letzten der zehn römischen Exil leben muss – fern seines Heimatstaates Strathclyde Concertos für das Scottish Chamber Naxos Quartets Nos. 9 and 10 Florenz, dessen Regierung er wegen ihrer Orchestra getan hatte. Ich hielt stand. Zwar ist der dritte „Rechtsverletzung und Schande“ tadelt. Satz als Passamezzo Farewell bezeichnet, doch ohne Der zweite Satz ist auch jetzt (wie die ursprüngliche alle Wehmut – wenngleich es durchaus Rückblicke gibt. Maggini Quartet Skizze) ein Largo, in dem der erste Teil des Kopfsatzes Der erste Satz ist ein Broken Reel. Die Umrisse der langsam durchgeführt wird, heftig unterbrochen von der Tanzform sind vorhanden, die Rhythmen aber sind verworfenen Musik, die hier integriert und verstärkt gebrochen, derweil hinter der barocken Oberfläche eine erscheint. -

Other Minds in Association with the Berkeley Art

OTHER MINDS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/ PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE & THE MISSION DOLORES BASILICA PRESENTS OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL 22 FEBRUARY 18, 19 & MAY 20, 2017 MISSION DOLORES BASILICA, SAN FRANCISCO & BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE, BERKELEY 2 O WELCOME FESTIVAL TO OTHER MINDS 22 OF NEW MUSIC The 22nd Other Minds Festival is present- 4 Message from the Artistic Director ed by Other Minds in association with the 8 Lou Harrison Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive & the Mission Dolores Basilica 9 In the Composer’s Words 10 Isang Yun 11 Isang Yun on Composition 12 Concert 1 15 Featured Artists 23 Film Presentation 24 Concert 2 29 Featured Artists 35 Timeline of the Life of Lou Harrison 38 Other Minds Staff Bios 41 About the Festival 42 Festival Supporters: A Gathering of Other Minds 46 About Other Minds This booklet © 2017 Other Minds, All rights reserved 3 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR WELCOME TO A SPECIAL EDITION OF THE OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL— A TRIBUTE TO ONE OF THE MOST GIFTED AND INSPIRING FIGURES IN THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN CLASSICAL MUSIC, LOU HARRISON. This is Harrison’s centennial year—he was born May 14, 1917—and in addition to our own concerts of his music, we have launched a website detailing all the other Harrison fêtes scheduled in his hon- or. We’re pleased to say that there will be many opportunities to hear his music live this year, and you can find them all at otherminds.org/lou100/. Visit there also to find our curated compendium of Internet links to his work online, photographs, videos, films and recordings. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Peter Maxwell Davies’s ’Revelation and Fall’: Influence study and analysis Thesis How to cite: Rees, Jonathan (2011). Peter Maxwell Davies’s ’Revelation and Fall’: Influence study and analysis. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2011 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000ed80 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk 0 º. ar2 ý ýrwz. t cl-c- Z1 JonathanRees PhD 1131 PETER MAXWELL DAVIES'S REVELATIONAND FALL: INFLUENCE STUDY AND ANALYSIS VOLUME ONE - TEXT A thesis submitted for the degreeof PhD in Music. Submitted: 17thSeptember 2010 ß'C' oc Awr% a: 20 _$ t 1Zc -t i ABSTRACT This thesis is an analysis of Peter Maxwell Davies's Revelation and Fall, through the influences that affect the development of its musical language and adoption of the expressionist aesthetic. Each chapter concentrates upon one aspect of the work: (1) its deployment of precompositional processes of thematic transformation; (2) the superimposition of different levels of structural organization; (3) motivic working within thematic transformation and contrapuntal devices; (4) experiments with timbre and the manipulation of temporal flow; and (5) the dramatic and aesthetic influences that shapethe presentationof the work. -

HENRY and LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL of MUSIC SPRING 2017 Fanfare

HENRY AND LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC SPRING 2017 fanfare 124488.indd 1 4/19/17 5:39 PM first chair A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN One sign of a school’s stature is the recognition received by its students and faculty. By that measure, in recent months the eminence of the Bienen School of Music has been repeatedly reaffirmed. For the first time in the history of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, this spring one of the contestants will be a Northwestern student. EunAe Lee, a doctoral student of James Giles, is one of only 30 pianists chosen from among 290 applicants worldwide for the prestigious competition. The 15th Van Cliburn takes place in May in Ft. Worth, Texas. Also in May, two cello students of Hans Jørgen Jensen will compete in the inaugural Queen Elisabeth Cello Competition in Brussels. Senior Brannon Cho and master’s student Sihao He are among the 70 elite cellists chosen to participate. Xuesha Hu, a master’s piano student of Alan Chow, won first prize in the eighth Bösendorfer and Yamaha USASU Inter national Piano Competition. In addition to receiving a $15,000 cash prize, Hu will perform with the Phoenix Symphony and will be presented in recital in New York City’s Merkin Concert Hall. Jason Rosenholtz-Witt, a doctoral candidate in musicology, was awarded a 2017 Northwestern Presidential Fellowship. Administered by the Graduate School, it is the University’s most prestigious fellowship for graduate students. Daniel Dehaan, a music composition doctoral student, has been named a 2016–17 Field Fellow by the University of Chicago. -

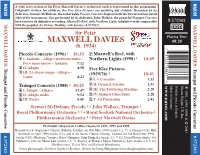

Maxwell Davies’S Orchestral Work Is Represented in This Programme

NAXOS NAXOS A wide cross-section of Sir Peter Maxwell Davies’s orchestral work is represented in this programme. Originally written for children, the Five Klee Pictures are anything but childish. Recorded by its dedicatee, Stewart McIlwham, the remarkable Piccolo Concerto displays both the lyrical and mercurial sides of the instrument. Also performed by its dedicatee, John Wallace, the powerful Trumpet Concerto here receives its definitive recording. Maxwell’s Reel, with Northern Lights inhabits worlds comparable 8.572363 MAXWELL DAVIES: MAXWELL DAVIES: with the popular An Orkney Wedding with Sunrise (8.572352). DDD Sir Peter Playing Time MAXWELL DAVIES 68:28 (b. 1934) 7 Piccolo Concerto (1996) 1 16:33 7 Maxwell’s Reel, with 47313 23637 1 I. Andante – Allegro moderato molto – Northern Lights (1998) 3 10:49 Poco meno mosso – Andante 7:12 Trumpet and Piccolo Concertos Trumpet 2 II. Adagio 4:58 Five Klee Pictures and Piccolo Concertos Trumpet 3 III. Lo stesso tempo – Allegro – (1959/76) 4 10:41 Lento 4:23 8 I. A Crusader 1:35 4 9 www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ Trumpet Concerto (1988) 2 30:25 II. Oriental Garden 1:35 Naxos Rights US, Inc. 4 I. Adagio – Allegro 13:47 0 III. The Twittering Machine 2:20 1991, 1995, 1998 & 5 II. Adagio molto 9:54 ! IV. Stained-Glass Saint 2:28 6 III. Presto 6:45 @ V. Ad Parnassum 2:43 Stewart McIlwham, Piccolo 1 • John Wallace, Trumpet 2 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 1, 3 • Royal Scottish National Orchestra 2 Philharmonia Orchestra 4 • Peter Maxwell Davies Ꭿ Previously released on Collins Classics in 1991, 1995 and 1998 2013 Recorded at St Augustine's Church, Kilburn, London, on 18th May, 1998 (tracks 1-3, 7); at Glasgow City Hall, Scotland, in April 1990 (tracks 4-6), and at All Saints Church, Tooting, London, on 3rd December, 1994 8.572363 8.572363 (tracks 8-12) • Producer: Veronica Slater • Engineer: John Timperley (tracks 1-3, 7-12); David Flower (tracks 4-6) Publishers: Chester Music Ltd. -

MAXWELL DAVIES Symphony No

Peter MAXWELL DAVIES Symphony No. 6 Time and the Raven • An Orkney Wedding with Sunrise Royal Philharmonic Orchestra • Maxwell Davies Peter Maxwell Davies (b. 1934) becomes a symbol of warning – in my work, dark music At the outset, we hear guests arriving, out of extremely Symphony No. 6 • Time and the Raven • An Orkney Wedding with Sunrise hints at what could be, were attitudes to nationalism not to bad weather, at the hall. This is followed by the modifyʼ. Hence the non-triumphant ending, hinting at the processional, where the guests are solemnly received by Symphony No. 6 (1996) Time and the Raven (1995) manner in which the anthems ʻcan get along together, and the bride and bridegroom, and presented with their first accommodate each other. This is, perhaps, the most glass of whisky. The band tunes up, and we get on with Symphony No. 6 was composed during the first half of The art of the occasional overture, commissioned for a “real” for which we can hopeʼ. Despite the note of caution, the dancing proper. This becomes ever wilder, as all 1996. It has three movements. The starting-off point is a specific celebration, has given rise to some remarkably the orchestration is of suitably celebratory proportions, concerned feel the results of the whisky, until the lead slow tune from Time and the Raven, a work fluent and even inspired exercises in the genre in the with triple woodwind, a sizeable (though by no means fiddle can hardly hold the band together any more. We commissioned to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the nineteenth century. -

PETER MAXWELL DAVIES an Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise

PETER MAXWELL DAVIES An Orkney Wedding, With Sunrise Scottish Chamber Orchestra Ben Gernon Sean Shibe guitar Scottish Chamber Orchestra Ben Gernon conductor Sean Shibe guitar Peter Maxwell Davies (1934–2016) 1. Concert Overture: Ebb Of Winter ..................................................... 17:41 Hill Runes* 2. Adagio – Allegro moderato ................................................................ 1:58 3. Allegro (with several changes of tempo) ........................................ 0:50 4. Vivace scherzando ............................................................................... 0:48 5. Adagio molto .......................................................................................... 2:27 6. Allegro (dying away into ‘endless’ silence) ..................................... 1:55 7. Last Door Of Light ............................................................................... 16:38 8. Farewell To Stromness* ...................................................................... 4:26 9. An Orkney Wedding, With Sunrise ................................................. 12:34 Total Running Time: 59 minutes *solo guitar Recorded at Usher Hall, Edinburgh, UK 14–16 September 2015 Produced by John Fraser (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise, Ebb of Winter, Last Door of Light) and Philip Hobbs (Farewell to Stromness and Hill Runes) Recorded by Calum Malcolm (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise, Ebb of Winter, Last Door of Light) and Philip Hobbs (Farewell to Stromness and Hill Runes) Post-production by Julia Thomas Cover image by -

Iconnotations Production Info Sm

Red Note Ensemble & Matthew Hawkins Iconnotations Koechlin Excerpts from Les Heures Persanes Maxwell Davies Vesalii Icones A new production and choreography of the iconic Peter Maxwell Davies work Vesalii Icones. Written in 1969 this is one of Peter Maxwell Davies’s classic works of concert-hall music theatre. An extraordinarily dramatic, multi-layered fusion of dance and music, its shape superimposes the 14 stations of the Cross on a series of 16th-century anatomical drawings by Vesalius, with a dancer and a solo cellist as the protagonists. Scored for the classic Fires of London Sextet line-up the work is filled with unconventional percussion instruments, a honky tonk piano and much allusion to foxtrots as well as medieval and renaissance music. In contrast to the vibrant sonorities of Vesalii Icones, the first half features the atmospheric piano works inspired by Persia and written during the First World War by the prolific French composer Charles Koechlin. “It was touching, eccentric, wry, surprising, profound. I adored the nods to surrealist art. Goodness, there was so much there.” “Superb performance of Maxwell Davies' Vesalii Icones. Virtuosic playing of cellist Lionel Handy was exceptional, pacing and balancing by conductor Pierre-Andre Valade very thoughtful. Humanity of Hawkins choreography was heart rending.” Audience feedback Matthew Hawkins Red Note Ensemble Matthew Hawkins is Royal Ballet School trained. Hawkins’ shift Red Note performs the established classics of contemporary from ballet to contemporary practice involved his being a founder music, commissions new music, develops the work of new and member of Second Stride and Michael Clark dance companies, emerging composers and performers from Scotland and around studying Cunningham technique at source and presenting his the world, and finds new spaces and new ways of performing own work, including as Artistic Director of Imminent Dancers contemporary music to attract new audiences.