PETER MAXWELL DAVIES an Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

SIR PETER MAXWELL DAVIES: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1955: “Burchiello” for sixteen percussion instruments “Opus Clavicembalisticum(Sorabji)” for orchestra “Work on a Theme by Thomas Tompkins” for orchestra 1957: St. Michael”-Sonata for seventeen wind instruments, op.6: 17 minutes 1958: “Prolation” for orchestra, op.8: 20 minutes 1959: “Five Canons” for school/amateur orchestra “Pavan and Galliard” for school/amateur orchestra “Variations on a Theme for Chords” for school/amateur orchestra 1959/76: Five Klee Pictures for orchestra, op.12: 10 minutes + (Collins cd) 1960: Three Pieces for junior orchestra 1961: Fantasy on the National Anthem for school/amateur orchestra 1962: First Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op.19: 11 minutes Sinfonia for chamber orchestra, op. 20: 23 minutes + Regis d) 1963: “Veni Sancte Spiritus” for soprano, contralto, tenor, baritone, chorus and orchestra, op.22: 20 minutes 1964: Second Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op. 23: 39 minutes + (Decca cd) 1967: Songs to Words by Dante for baritone and small orchestra 1969: Foxtrot “St. Thomas Wake” for orchestra, op.37: 20 minutes + (Naxos cd) Motet “Worldes Bliss” for orchestra, op.38: 37 minutes 1971: Suite from “The Boyfriend” for small orchestra, op.50b: 26 minutes * + (Collins cd) 1972: “Walton Tribute” for orchestra Masque “Blind Man’s Buff” for soprano or treble, mezzo-soprano, mime and small orchestra, op.51: 20 minutes 1973: “Stone Liturgy-Runes from a House of the Dead” for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, -

The Persistence of Parody in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Insight - University of Cumbria The Persistence of Parody in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies Richard E McGregor It’s all about time. Indeed there is not a single piece of musical composition that is not in some way about time. And for Davies the manipulation of time is rooted in his understanding of late Medieval and early Renaissance musical techniques and practices refracted through post 12-note pitch manipulation. In this article I take to task the uncritical use of terminology in relation to the music of Peter Maxwell Davies. Though my generating text is the quotation from John Warnaby’s 1990 doctoral thesis: Since parody is implied in the notion of using pre-existing material as a creative model, it can be argued that, as traditionally understood, it is rarely absent from Maxwell Davies’s music[1] this is in no wise a criticism of Warnaby for whom I have much respect, and especially his ability to be able to perceive patterns, trends and unifying features between works and across extended periods of time. Rather, it is a commentary on particular aspects of Davies’s music which are often linked together under the catch-all term ‘parody’: EXAMPLE 1: Dali’s The Persistence of Memory[2] I take as my starting point the painting The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali, a painting which operates on a number of levels, the most obvious, because of the immediate imagery, being that is has something to do with time. -

Download the Full Programme

Autumn Special Online from 8 September 2020, 1:00pm | Holy Trinity Church, Haddington Chloë Hanslip violin Danny Driver piano Ludwig van Beethoven Violin Sonata No. 1 in D Major, Op. 12, No. 1 Sergey Prokofiev Five Melodies Ludwig van Beethoven Violin Sonata No. 10 in G Major, Op. 96 The Lammermuir Festival is a registered charity in Scotland SC049521 Ludwig van Beethoven Violin Sonata No. 1 in D Major, Op. 12, No. 1 1. Allegro con brio 2. Tema con variazioni: Andante con moto 3. Rondo: Allegro Beethoven’s first three violin sonatas were composed between 1797–98. Although they were dedicated to Antonio Salieri, with whom he might briefly have studied, they show the unmistakable influence Mozart made on Beethoven’s music at the time, as he acquired full fluency in the Viennese Classical style. And in the customary Classical style, they are indicated as sonatas ‘for pianoforte and violin’, with both instruments having a more or less equal role. While the Op. 12 violin sonatas are not necessarily as formally daring as the piano sonatas of the same period, they reveal Beethoven’s firm grasp of how to write idiomatically for the violin, as well as his increasing understanding of how to create a sonata style based on the apparent unification of two opposing forces. The opening movement begins with a bold unison figure, which quickly gives way to a sonorous first subject. In the central development section, rapid passages of semiquavers are passed between violin and piano in quick sequence, making for a vigorous dialogue. The middle movement takes the form of a theme and variations, the theme being audibly based on the opening figure of the previous movement. -

Download Booklet

a song more silent new works for remembrance Sally Beamish | Cecilia McDowall Tarik O’Regan | Lynne Plowman Portsmouth Grammar School Chamber Choir London Mozart Players Nicolae Moldoveanu It was J. B. Priestley who first drew attention Hundreds of young people are given the to the apparent contradiction on British war opportunity to participate as writers, readers, memorials: the stony assertion that ‘Their Name singers and instrumentalists, working in Liveth for Evermore’ qualified by the caution collaboration with some of our leading ‘Lest We Forget’. composers to create works that are both thoughtful and challenging in response to ideas It is a tension which reminds us of the need for of peace and war. each generation to remember the past and to express its own commitment to a vision of peace. E. E. Cummings’ poem these children singing in stone, set so evocatively by Lynne Plowman, The pupils of Portsmouth Grammar School are offers a vision of “children forever singing” as uniquely placed to experience this. The school images of stone and blossom intertwine. These is located in 19th-century barracks at the heart new works for Remembrance are an expression of a Garrison City, once the location of Richard of hope from a younger generation moved and the Lionheart’s palace. Soldiers have been sent inspired by “a song more silent”. around the world from this site for centuries. It has been suggested that more pupils lost their James Priory Headmaster 2008 lives in the two World Wars than at any other school of comparable size. Today, as an inscription on the school archway celebrates, it is a place where girls and boys come to learn and play. -

Peter Maxwell Davies Eigentliche Grund Dafür Klar: Ich Wollte Keinen Dicken Deutsche Fassung: Cris Posslac

557400 bk Max 14/7/08 10:53 Page 4 diszipliniert, wobei, wie ich glaube, durch die recht schwarzen Schluss-Strich ziehen, wollte nicht, dass das genaue und komplexe Arbeit mit magischen Quadraten ein letztes Quartett sein soll. Ich musste die Tür offen einige Ordnung entstanden ist. lassen: Mir hat die Arbeit an den Naxos-Quartetten so PETER Ich habe auch auf das dritte Naxos Quartet viel Freude gemacht (und ich habe dabei vielleicht sogar verwiesen. Dort habe ich dem Violoncello einen Vers das eine oder andere gelernt), dass theoretisch daraus von Michelangelo unterlegt, der mit den Worten noch mehr entstehen könnte. MAXWELL DAVIES beginnt: Caro me il sonno, e più l’esser di sasso („Der Eine weitere Versuchung bestand darin, in einer Schlaf ist mir teuer, und von Stein zu sein, ist teurer“). feierlichen Abschiedssequenz auf jedes der vorigen In diesem Gedicht beklagt der Dichter, dass er im Quartette anzuspielen, wie ich das im letzten der zehn römischen Exil leben muss – fern seines Heimatstaates Strathclyde Concertos für das Scottish Chamber Naxos Quartets Nos. 9 and 10 Florenz, dessen Regierung er wegen ihrer Orchestra getan hatte. Ich hielt stand. Zwar ist der dritte „Rechtsverletzung und Schande“ tadelt. Satz als Passamezzo Farewell bezeichnet, doch ohne Der zweite Satz ist auch jetzt (wie die ursprüngliche alle Wehmut – wenngleich es durchaus Rückblicke gibt. Maggini Quartet Skizze) ein Largo, in dem der erste Teil des Kopfsatzes Der erste Satz ist ein Broken Reel. Die Umrisse der langsam durchgeführt wird, heftig unterbrochen von der Tanzform sind vorhanden, die Rhythmen aber sind verworfenen Musik, die hier integriert und verstärkt gebrochen, derweil hinter der barocken Oberfläche eine erscheint. -

4992975-119B27-5060189560608.Pdf

A brand new suite of music and words based on Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll with text by Louis de Bernières 1 All in the Golden Afternoon 2.12 17 The Queen’s Croquet Ground 2 All in the Golden Afternoon (Sally Beamish b.1956)* 3.46 (Richard Dubugnon b.1968) 8.55 3 Down the Rabbit Hole 1.30 18 The Mock-Turtle Soup (Ilya Gringolts b.1982) 5.12 4 Down the Rabbit Hole (Roxanna Panufnik b.1968) 1.54 19 The Lobster Quadrille 1.25 5 The Pool of Tears 0.45 20 The Lobster Quadrille (Colin Matthews b.1946) 1.45 6 The Pool of Tears (Mark-Anthony Turnage b.1960) 4.10 21 Who Stole the Tarts? 0.46 7 A Caucus Race 0.49 22 Who Stole the Tarts? (Gwilym Simcock b.1981) 3.43 8 A Caucus Race (Stuart MacRae b.1976) 2.17 23 Alice’s Evidence 1.11 9 The Rabbit sends in a Little Bill (Poul Ruders b.1949) 2.22 24 Alice’s Evidence (Augusta Read Thomas b.1964) 2.33 10 Advice from a Caterpillar 2.21 Total time 61.07 11 Advice from a Caterpillar (Howard Blake b.1938) 4.52 12 Pig and Pepper 1.18 Maureen Lipman narrator 13 Pig and Pepper (Carl Davis b.1936) 2.07 Matthew Trusler violin 14 A Mad Tea-Party 1.21 Ashley Wass piano 15 A Mad Tea-Party (Stephen Hough b.1961) 2.25 *Elise Smith triangle 16 The Queen’s Croquet Ground 1.25 2 WONDERLAND AND THE LENNY TRUSLER CHILDREN’S FOUNDATION From the original idea through to the release of this album, Wonderland has constantly grown and developed to become the most exciting and ambitious project with which we’ve ever been involved. -

Britten in Beijing

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited February 2013 2013/1 Reich Radio Rewrite Britten in Beijing Steve Reich’s new ensemble work, with first performances in Included in this issue: The Britten centenary sees the composer’s drawings, resulting in a spectacular series of the UK and US in March, draws inspiration from songs by music celebrated worldwide including many animal lanterns handcrafted in Shangdong van der Aa Radiohead. works receiving territorial premieres, from Province. The production used the biblical Interview about his new 3D song through to reworkings by Stravinsky. South America to Asia and the Antipodes. tale of Noah to explore contemporary film opera Sunken Garden “It was not my intention to make anything like As an upbeat to this year’s events, the first ecological concerns. Through a series of ‘variations’ on these songs, but rather to Britten opera was staged in China with a educational projects, Noye’s Fludde provided draw on their harmonies and sometimes Noye’s Fludde collaboration between an illustration of man’s struggle with the melodic fragments and work them into my Northern Ireland Opera, the KT Wong environment and the significance of flood own piece. As to actually hearing the original Foundation and the Beijing Music Festival. mythology to both Chinese and Western cultures. songs, the truth is – sometimes you hear First staged in Belfast Zoo last summer as them and sometimes you don’t.” part of the Cultural Olympiad, Oliver Mears’s Overseas Britten highlights in 2013 include Photo: Wonge Bergmann Reich encountered the music of Radiohead production transferred in October to Beijing as territorial opera premieres in Brazil, Chile, following a performance by Jonny part of the UK Now Festival. -

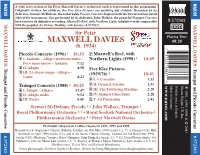

Maxwell Davies’S Orchestral Work Is Represented in This Programme

NAXOS NAXOS A wide cross-section of Sir Peter Maxwell Davies’s orchestral work is represented in this programme. Originally written for children, the Five Klee Pictures are anything but childish. Recorded by its dedicatee, Stewart McIlwham, the remarkable Piccolo Concerto displays both the lyrical and mercurial sides of the instrument. Also performed by its dedicatee, John Wallace, the powerful Trumpet Concerto here receives its definitive recording. Maxwell’s Reel, with Northern Lights inhabits worlds comparable 8.572363 MAXWELL DAVIES: MAXWELL DAVIES: with the popular An Orkney Wedding with Sunrise (8.572352). DDD Sir Peter Playing Time MAXWELL DAVIES 68:28 (b. 1934) 7 Piccolo Concerto (1996) 1 16:33 7 Maxwell’s Reel, with 47313 23637 1 I. Andante – Allegro moderato molto – Northern Lights (1998) 3 10:49 Poco meno mosso – Andante 7:12 Trumpet and Piccolo Concertos Trumpet 2 II. Adagio 4:58 Five Klee Pictures and Piccolo Concertos Trumpet 3 III. Lo stesso tempo – Allegro – (1959/76) 4 10:41 Lento 4:23 8 I. A Crusader 1:35 4 9 www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ Trumpet Concerto (1988) 2 30:25 II. Oriental Garden 1:35 Naxos Rights US, Inc. 4 I. Adagio – Allegro 13:47 0 III. The Twittering Machine 2:20 1991, 1995, 1998 & 5 II. Adagio molto 9:54 ! IV. Stained-Glass Saint 2:28 6 III. Presto 6:45 @ V. Ad Parnassum 2:43 Stewart McIlwham, Piccolo 1 • John Wallace, Trumpet 2 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 1, 3 • Royal Scottish National Orchestra 2 Philharmonia Orchestra 4 • Peter Maxwell Davies Ꭿ Previously released on Collins Classics in 1991, 1995 and 1998 2013 Recorded at St Augustine's Church, Kilburn, London, on 18th May, 1998 (tracks 1-3, 7); at Glasgow City Hall, Scotland, in April 1990 (tracks 4-6), and at All Saints Church, Tooting, London, on 3rd December, 1994 8.572363 8.572363 (tracks 8-12) • Producer: Veronica Slater • Engineer: John Timperley (tracks 1-3, 7-12); David Flower (tracks 4-6) Publishers: Chester Music Ltd. -

The Seafarer Trio Apaches Sir Willard White

The Seafarer Trio apacheS Sir Willard WhiTe claude deBuSSy (1862-1918) arr. Sally BeamiSh (b.1956) The Seafarer Project La Mer it was during ashley’s festival in the beautiful city of lincoln that we played our first 1 de l’aube a midi sur la mer. Tres lent 8:26 concert together as an official trio, with a programme that included The Seafarer . 2 Jeux de Vagues. allegro 7:19 3 dialogue du vent et de la mer. anime et tumultueux 8:17 That week, while we worked on the piece and formed ideas for our new ensemble, we became increasingly excited by the idea of challenging what we thought of as Sally BeamiSh (b.1956) conventional trio programming; seeking collaborations which would bring something 4 The Seafarer – for voice and piano trio 28:45 fresh to the genre, and – perhaps most importantly – commissioning new works would be important elements of our future as a group. Total time 52:49 one thing was clear from the very beginning: The Seafarer should be the focal point for our first album. We’d fallen in love with the piece (and the poem) and it represented TRIO APACHES exactly the kind of collaborative repertoire we wanted to explore. a long and fruitless matthew Trusler (violin) search for a suitable sea-related companion piece led us to the conclusion that this Thomas carroll (cello) was the moment for our first commission. asking Sally Beamish to transcribe La Mer ashley Wass (piano) quickly became our favourite idea. Sir Willard White (voice) our proposal was initially met with polite laughter from Sally, but we kept nagging away and soon persuaded her it was something that absolutely had to be done. -

Iconnotations Production Info Sm

Red Note Ensemble & Matthew Hawkins Iconnotations Koechlin Excerpts from Les Heures Persanes Maxwell Davies Vesalii Icones A new production and choreography of the iconic Peter Maxwell Davies work Vesalii Icones. Written in 1969 this is one of Peter Maxwell Davies’s classic works of concert-hall music theatre. An extraordinarily dramatic, multi-layered fusion of dance and music, its shape superimposes the 14 stations of the Cross on a series of 16th-century anatomical drawings by Vesalius, with a dancer and a solo cellist as the protagonists. Scored for the classic Fires of London Sextet line-up the work is filled with unconventional percussion instruments, a honky tonk piano and much allusion to foxtrots as well as medieval and renaissance music. In contrast to the vibrant sonorities of Vesalii Icones, the first half features the atmospheric piano works inspired by Persia and written during the First World War by the prolific French composer Charles Koechlin. “It was touching, eccentric, wry, surprising, profound. I adored the nods to surrealist art. Goodness, there was so much there.” “Superb performance of Maxwell Davies' Vesalii Icones. Virtuosic playing of cellist Lionel Handy was exceptional, pacing and balancing by conductor Pierre-Andre Valade very thoughtful. Humanity of Hawkins choreography was heart rending.” Audience feedback Matthew Hawkins Red Note Ensemble Matthew Hawkins is Royal Ballet School trained. Hawkins’ shift Red Note performs the established classics of contemporary from ballet to contemporary practice involved his being a founder music, commissions new music, develops the work of new and member of Second Stride and Michael Clark dance companies, emerging composers and performers from Scotland and around studying Cunningham technique at source and presenting his the world, and finds new spaces and new ways of performing own work, including as Artistic Director of Imminent Dancers contemporary music to attract new audiences. -

March 2019 2 •

2018/19 Season January - March 2019 2 • This spring, two of today's greatest Lieder interpreters, the German baritone Christian Gerhaher and his regular pianist Gerold Huber, return to survey one of the summits of the repertoire, Schubert’s psychologically intense Winterreise. Harry Christophers and The Sixteen join us with a programme of odes, written to welcome Charles II back Director’s to London from his visits to Newmarket, alongside excerpts from Purcell's incidental music to Theodosius, Nathaniel Lee's 1680 tragedy. Introduction Leading Schubert interpreter Christian Zacharias delves into the composer’s unique melodic, harmonic and thematic flourishes in his lecture-recital. Through close examination of these musical hallmarks and idiosyncrasies, he takes us on a journey to the very essence of Schubert’s style. With her virtuosic ability to sing anything from new works to Baroque opera and Romantic Lieder with exceptional quality, Marlis Petersen is one of the most enterprising singers today. Her residency continues with two concerts, sharing the stage with fellow singers and accompanists of international acclaim. This year’s Wigmore Hall Learning festival, Sense of Home, celebrates the diversity and multicultural melting pot that is London and the borough of Westminster, reflects on Wigmore Hall as a place many call home, and invites you to explore what ‘home’ means to you. One of the most admired singers of the present day, Elīna Garanča, will open the 2018/19 season at the Metropolitan Opera as Dalila in Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila. Her programme in February – comprising four major cycles – includes Wagner's Wesendonck Lieder, two of which were identified by the composer himself as studies for Tristan und Isolde. -

Barbican Announces the Return of Live Audiences to the Hall, with In

For immediate release: 13 April 2021 Barbican announces the return of live audiences to the Hall, with in-person tickets going on sale for Live from the Barbican concerts from 17 May onwards; featuring Shirley Collins, This is The Kit, world premiere of Errollyn Wallen’s Dido’s Ghost, Sheku & Isata Kanneh-Mason, George the Poet, and Britten Sinfonia with Thomas Adès Today the Barbican announces that in-person tickets for concerts scheduled after 17 May 2021 will go on sale to Barbican patrons on Wednesday 21 April, Barbican members on Thursday 22 April and will be on general sale from Friday 23 April 2021. The spring/summer concerts of the acclaimed Live from the Barbican series will take place as livestreams until 17 May and then continue to be accessible online for a global livestream audience, as well as for a reduced, socially distanced live audience in the Barbican Hall. Tickets are £20 – 40 for live audiences in the Barbican Hall, and £12.50 to access the livestreams. Once livestream tickets are bought ahead of the concert, audiences have an additional 48 hours to re-watch the concert after the event. Discounted tickets at £5 and £10 are available to 14 – 25-year-olds through Young Barbican and over 1000 free stream passes are being offered to schools and community groups in London, as well as schools further afield in Manchester, Harlow and Norfolk, through Barbican Creative Learning. In line with Government guidance, safety measures will be in place, including operating at a reduced, 50% capacity in the Hall, one-way systems to ensure a safe and socially distanced flow of visitors through the space and sanitiser stations.