Peter Maxwell Davies' Worst Nightmare: Staging the Unsacred In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HCS Full Repertoire

Season date composer piece soloists Orchestra and location Conductor and any instrumentalists additional choirs 1938/39 Rehearsals only Ursula Nettleship 1939/40 23rd March 1940 Handel Messiah Winifred Bury, Haileybury College Haileybury Combined choirs inc. Mervyn Saunders, Orchestra HCS Ifor Hughes, Eric Bravington (trumpet) Dr Reginald Johnson, Haileybury 1940/41 22nd March 1941 Coleridge-Taylor Hiawatha's Wedding Feast Haileybury HCS and Haileybury College Choir 10th May 1941 Brahms How lovely is thy dwelling Hertford Orchestra Shire Hall Frank Greenfield place Pinsuti A Spring Song arr. Greenfield There is a lady sweet and kind Stanford The Blue Bird Corydon, Arise! 1940/41 July 1941 Repertoire unknown Bishops Stortford Frank Greenfield Music Festival 1942/43 12th December Brahms The Serenade Hertford Orchestra Shire Hall, Hector McCurrach 1942 Hertford Stanford The Revenge Weelkes Like two proud armies 27th May 1943 Handel Messiah Margaret Field-Hyde Leader: Dorothy Loynes W All Saints' Reginald Jacques (soprano), Eileen J Comley (organ) Church, Hertford (combined choirs of Pilcher (alto), Peter Hector McCurrach Broxbourne, Pears (tenor), Henry (continuo) Cheshunt, Hertford, Cummings, bass) Hertford Free Churches, Haileybury, Much Hadham, Thundridge, Ware) 1943/44 Date unknown Haydn The Creation unknown unknown Hertford Music Club concert with Hertford and other choirs 1944/45 7th December Bach Christmas Oratorio Kathleen Willson Orchestra of wood wind Hertford Grammar Hector McCurrach 1944 (contralto), Elster and strings School -

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

SIR PETER MAXWELL DAVIES: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1955: “Burchiello” for sixteen percussion instruments “Opus Clavicembalisticum(Sorabji)” for orchestra “Work on a Theme by Thomas Tompkins” for orchestra 1957: St. Michael”-Sonata for seventeen wind instruments, op.6: 17 minutes 1958: “Prolation” for orchestra, op.8: 20 minutes 1959: “Five Canons” for school/amateur orchestra “Pavan and Galliard” for school/amateur orchestra “Variations on a Theme for Chords” for school/amateur orchestra 1959/76: Five Klee Pictures for orchestra, op.12: 10 minutes + (Collins cd) 1960: Three Pieces for junior orchestra 1961: Fantasy on the National Anthem for school/amateur orchestra 1962: First Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op.19: 11 minutes Sinfonia for chamber orchestra, op. 20: 23 minutes + Regis d) 1963: “Veni Sancte Spiritus” for soprano, contralto, tenor, baritone, chorus and orchestra, op.22: 20 minutes 1964: Second Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op. 23: 39 minutes + (Decca cd) 1967: Songs to Words by Dante for baritone and small orchestra 1969: Foxtrot “St. Thomas Wake” for orchestra, op.37: 20 minutes + (Naxos cd) Motet “Worldes Bliss” for orchestra, op.38: 37 minutes 1971: Suite from “The Boyfriend” for small orchestra, op.50b: 26 minutes * + (Collins cd) 1972: “Walton Tribute” for orchestra Masque “Blind Man’s Buff” for soprano or treble, mezzo-soprano, mime and small orchestra, op.51: 20 minutes 1973: “Stone Liturgy-Runes from a House of the Dead” for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

The Persistence of Parody in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Insight - University of Cumbria The Persistence of Parody in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies Richard E McGregor It’s all about time. Indeed there is not a single piece of musical composition that is not in some way about time. And for Davies the manipulation of time is rooted in his understanding of late Medieval and early Renaissance musical techniques and practices refracted through post 12-note pitch manipulation. In this article I take to task the uncritical use of terminology in relation to the music of Peter Maxwell Davies. Though my generating text is the quotation from John Warnaby’s 1990 doctoral thesis: Since parody is implied in the notion of using pre-existing material as a creative model, it can be argued that, as traditionally understood, it is rarely absent from Maxwell Davies’s music[1] this is in no wise a criticism of Warnaby for whom I have much respect, and especially his ability to be able to perceive patterns, trends and unifying features between works and across extended periods of time. Rather, it is a commentary on particular aspects of Davies’s music which are often linked together under the catch-all term ‘parody’: EXAMPLE 1: Dali’s The Persistence of Memory[2] I take as my starting point the painting The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali, a painting which operates on a number of levels, the most obvious, because of the immediate imagery, being that is has something to do with time. -

Peter Maxwell Davies Eigentliche Grund Dafür Klar: Ich Wollte Keinen Dicken Deutsche Fassung: Cris Posslac

557400 bk Max 14/7/08 10:53 Page 4 diszipliniert, wobei, wie ich glaube, durch die recht schwarzen Schluss-Strich ziehen, wollte nicht, dass das genaue und komplexe Arbeit mit magischen Quadraten ein letztes Quartett sein soll. Ich musste die Tür offen einige Ordnung entstanden ist. lassen: Mir hat die Arbeit an den Naxos-Quartetten so PETER Ich habe auch auf das dritte Naxos Quartet viel Freude gemacht (und ich habe dabei vielleicht sogar verwiesen. Dort habe ich dem Violoncello einen Vers das eine oder andere gelernt), dass theoretisch daraus von Michelangelo unterlegt, der mit den Worten noch mehr entstehen könnte. MAXWELL DAVIES beginnt: Caro me il sonno, e più l’esser di sasso („Der Eine weitere Versuchung bestand darin, in einer Schlaf ist mir teuer, und von Stein zu sein, ist teurer“). feierlichen Abschiedssequenz auf jedes der vorigen In diesem Gedicht beklagt der Dichter, dass er im Quartette anzuspielen, wie ich das im letzten der zehn römischen Exil leben muss – fern seines Heimatstaates Strathclyde Concertos für das Scottish Chamber Naxos Quartets Nos. 9 and 10 Florenz, dessen Regierung er wegen ihrer Orchestra getan hatte. Ich hielt stand. Zwar ist der dritte „Rechtsverletzung und Schande“ tadelt. Satz als Passamezzo Farewell bezeichnet, doch ohne Der zweite Satz ist auch jetzt (wie die ursprüngliche alle Wehmut – wenngleich es durchaus Rückblicke gibt. Maggini Quartet Skizze) ein Largo, in dem der erste Teil des Kopfsatzes Der erste Satz ist ein Broken Reel. Die Umrisse der langsam durchgeführt wird, heftig unterbrochen von der Tanzform sind vorhanden, die Rhythmen aber sind verworfenen Musik, die hier integriert und verstärkt gebrochen, derweil hinter der barocken Oberfläche eine erscheint. -

A 16Th-Century Meeting of England & Spain

A 16th-Century Meeting of England & Spain Blue Heron with special guest Ensemble Plus Ultra Saturday, October 15, 2011 · 8 pm | First Church in Cambridge, Congregational Sunday, October 16, 2011 · 4 pm | St. Ignatius of Antioch Episcopal Church, New York City A 16th-Century Meeting of England & Spain Blue Heron with special guest Ensemble Plus Ultra Saturday, October 15, 2011 · 8 pm | First Church in Cambridge, Congregational Sunday, October 16, 2011 · 4 pm | St. Ignatius of Antioch Episcopal Church, New York City Program Blue Heron & Ensemble Plus Ultra John Browne (fl. c. 1500) O Maria salvatoris mater a 8 Blue Heron Richard Pygott (c. 1485–1549) Salve regina a 5 intermission Ensemble Plus Ultra Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548–1611) Ave Maria a 8 Ave regina caelorum a 8 Victoria Vidi speciosam a 6 Vadam et circuibo civitatem a 6 Nigra sum sed formosa a 6 Ensemble Plus Ultra & Blue Heron Victoria Laetatus sum a 12 Francisco Guerrero (1528–99) Duo seraphim a 12 Blue Heron treble Julia Steinbok Teresa Wakim Shari Wilson mean Jennifer Ashe Pamela Dellal Martin Near contratenor Owen McIntosh Jason McStoots tenor Michael Barrett Sumner Thompson bass Paul Guttry Ulysses Thomas Peter Walker Scott etcalfe,M director Ensemble Plus Ultra Amy Moore, soprano Katie Trethewey, soprano Clare Wilkinson, mezzo-soprano David Martin, alto William Balkwill, tenor Tom Phillips, tenor Simon Gallear, baritone Jimmy Holliday, bass Michael Noone, director Blue Heron · 45 Ash Street, Auburndale MA 02466 (617) 960-7956 · [email protected] · www.blueheronchoir.org Blue Heron Renaissance Choir, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt entity. -

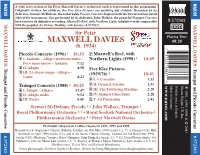

Maxwell Davies’S Orchestral Work Is Represented in This Programme

NAXOS NAXOS A wide cross-section of Sir Peter Maxwell Davies’s orchestral work is represented in this programme. Originally written for children, the Five Klee Pictures are anything but childish. Recorded by its dedicatee, Stewart McIlwham, the remarkable Piccolo Concerto displays both the lyrical and mercurial sides of the instrument. Also performed by its dedicatee, John Wallace, the powerful Trumpet Concerto here receives its definitive recording. Maxwell’s Reel, with Northern Lights inhabits worlds comparable 8.572363 MAXWELL DAVIES: MAXWELL DAVIES: with the popular An Orkney Wedding with Sunrise (8.572352). DDD Sir Peter Playing Time MAXWELL DAVIES 68:28 (b. 1934) 7 Piccolo Concerto (1996) 1 16:33 7 Maxwell’s Reel, with 47313 23637 1 I. Andante – Allegro moderato molto – Northern Lights (1998) 3 10:49 Poco meno mosso – Andante 7:12 Trumpet and Piccolo Concertos Trumpet 2 II. Adagio 4:58 Five Klee Pictures and Piccolo Concertos Trumpet 3 III. Lo stesso tempo – Allegro – (1959/76) 4 10:41 Lento 4:23 8 I. A Crusader 1:35 4 9 www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ Trumpet Concerto (1988) 2 30:25 II. Oriental Garden 1:35 Naxos Rights US, Inc. 4 I. Adagio – Allegro 13:47 0 III. The Twittering Machine 2:20 1991, 1995, 1998 & 5 II. Adagio molto 9:54 ! IV. Stained-Glass Saint 2:28 6 III. Presto 6:45 @ V. Ad Parnassum 2:43 Stewart McIlwham, Piccolo 1 • John Wallace, Trumpet 2 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 1, 3 • Royal Scottish National Orchestra 2 Philharmonia Orchestra 4 • Peter Maxwell Davies Ꭿ Previously released on Collins Classics in 1991, 1995 and 1998 2013 Recorded at St Augustine's Church, Kilburn, London, on 18th May, 1998 (tracks 1-3, 7); at Glasgow City Hall, Scotland, in April 1990 (tracks 4-6), and at All Saints Church, Tooting, London, on 3rd December, 1994 8.572363 8.572363 (tracks 8-12) • Producer: Veronica Slater • Engineer: John Timperley (tracks 1-3, 7-12); David Flower (tracks 4-6) Publishers: Chester Music Ltd. -

PETER MAXWELL DAVIES an Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise

PETER MAXWELL DAVIES An Orkney Wedding, With Sunrise Scottish Chamber Orchestra Ben Gernon Sean Shibe guitar Scottish Chamber Orchestra Ben Gernon conductor Sean Shibe guitar Peter Maxwell Davies (1934–2016) 1. Concert Overture: Ebb Of Winter ..................................................... 17:41 Hill Runes* 2. Adagio – Allegro moderato ................................................................ 1:58 3. Allegro (with several changes of tempo) ........................................ 0:50 4. Vivace scherzando ............................................................................... 0:48 5. Adagio molto .......................................................................................... 2:27 6. Allegro (dying away into ‘endless’ silence) ..................................... 1:55 7. Last Door Of Light ............................................................................... 16:38 8. Farewell To Stromness* ...................................................................... 4:26 9. An Orkney Wedding, With Sunrise ................................................. 12:34 Total Running Time: 59 minutes *solo guitar Recorded at Usher Hall, Edinburgh, UK 14–16 September 2015 Produced by John Fraser (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise, Ebb of Winter, Last Door of Light) and Philip Hobbs (Farewell to Stromness and Hill Runes) Recorded by Calum Malcolm (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise, Ebb of Winter, Last Door of Light) and Philip Hobbs (Farewell to Stromness and Hill Runes) Post-production by Julia Thomas Cover image by -

Iconnotations Production Info Sm

Red Note Ensemble & Matthew Hawkins Iconnotations Koechlin Excerpts from Les Heures Persanes Maxwell Davies Vesalii Icones A new production and choreography of the iconic Peter Maxwell Davies work Vesalii Icones. Written in 1969 this is one of Peter Maxwell Davies’s classic works of concert-hall music theatre. An extraordinarily dramatic, multi-layered fusion of dance and music, its shape superimposes the 14 stations of the Cross on a series of 16th-century anatomical drawings by Vesalius, with a dancer and a solo cellist as the protagonists. Scored for the classic Fires of London Sextet line-up the work is filled with unconventional percussion instruments, a honky tonk piano and much allusion to foxtrots as well as medieval and renaissance music. In contrast to the vibrant sonorities of Vesalii Icones, the first half features the atmospheric piano works inspired by Persia and written during the First World War by the prolific French composer Charles Koechlin. “It was touching, eccentric, wry, surprising, profound. I adored the nods to surrealist art. Goodness, there was so much there.” “Superb performance of Maxwell Davies' Vesalii Icones. Virtuosic playing of cellist Lionel Handy was exceptional, pacing and balancing by conductor Pierre-Andre Valade very thoughtful. Humanity of Hawkins choreography was heart rending.” Audience feedback Matthew Hawkins Red Note Ensemble Matthew Hawkins is Royal Ballet School trained. Hawkins’ shift Red Note performs the established classics of contemporary from ballet to contemporary practice involved his being a founder music, commissions new music, develops the work of new and member of Second Stride and Michael Clark dance companies, emerging composers and performers from Scotland and around studying Cunningham technique at source and presenting his the world, and finds new spaces and new ways of performing own work, including as Artistic Director of Imminent Dancers contemporary music to attract new audiences. -

Marcus Farnsworth’S Pilate and Matthew Long’S Peter Were Particularly Impressive the Arts Desk, Oct 9 2019

` HANDEL Brockes Passion, Arcangelo, Jonathan Cohen, Wigmore Hall Marcus Farnsworth’s Pilate and Matthew Long’s Peter were particularly impressive The Arts Desk, Oct 9 2019 BRITTEN Noye’s Fludde Theatre Royal, Stratford East Farnsworth’s excellent Noah Opera Magazine, September 2019 Marcus Farnsworth as Noah, leads the show’s adults with aplomb Geoff Brown, The Times July 5 2019 BACH St Matthew Passion, Ex Cathedra, Jeffrey Skidmore, Bristol, London & Birmingham Marcus Farnsworth’s Christ displayed more than a hint of controlled anger. Nick Kimberley, The Evening Standard, April 2019 The finest sensibilities came in the baritone of Marcus Farnsworth, realising both dignity and compassion in the role of Jesus and in the bass arias. Tireless throughout the evening, Farnsworth also added weight to the chorus bass line, like the other soloists following the practice of Bach’s time in this regard. Rian Evens, The Guardian, April 2019 Marcus Farnsworth PURCELL King Arthur, Gabrieli Consort & Players, Paul McCreesh, on tour in Australia Baritone The more sublime moments usually involved Anna Dennis, whose bell-like soprano rang true and with sigh-inducing expression in King Arthur’s well known solo, ‘Fairest Isle’, and in the passacaglia duet with baritone Marcus Farnsworth. His caresses, both of the luscious vocal and necessarily respectful physical kind, helped make this romantic interlude a performance highlight. Patricia Maunder, Limelight, February 2019 There was a stately, majestic call on the trumpet, leading Marcus Farnsworth to stand and with politician’s hand gestures and earnest expressions, eagerly joined by the crowd, to invoke the blessings of St George. -

Summer School Options - Sessions A: B: C: D

Orkney CoMA Contemporary Music Summer School with Allcomers Strings 1: Summer School options - sessions A: B: C: D: Fundamentals B: Mindfulness and Music Making Rolf Hind These sessions focus on fundamental aspects of musical creativity, the practice of physical embodiment, dealing with nervousness and addressing the function & place of music in our modern society. The course touches on aspects of yoga, meditation & mindfulness and considers how these can be used to benefit people in their musical practice. Suitable for all. Contemporary Ensembles (all instruments: wind, brass, strings, piano and percussion, except session D) A: Open Score Pilgrimage Workshop William Conway These sessions will serve as a workshop ensemble for pieces submitted for Alasdair Nicolson’s Pilgrimage composition course. It will also rehearse a new Open Score work by William Sweeney commissioned for the Orkney Summer School. All instrumentalists welcome. B: Stone Sounds James Weeks This course is suitable for all instruments and voices and, drawing on recent developments in archaeoacoustics, will concentrate on making sounds with voices and other sound sources at one or more of Orkney’s Neolithic sites. The aim is to develop these into an original work to be performed as part of a location-based concert towards the end of the course. In addition to the workshop sessions there will be two site visits, on Sunday on Tuesday morning, each leaving immediately after session A. Note that you will miss options C and D on Sunday. B: The Physicality of Sound Hollie Harding All performed sounds require sounding objects (instruments), actions (a physical movement that makes the object sound), agents (a performer carrying out a physical action), a localisation (a position in space and an environment to exist within) and an observer (audience). -

Schola Cantorum of Oxford ANDREW PARROTT Conductor

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Schola Cantorum of Oxford ANDREW PARROTT Conductor ANNABELLA TYSALL, Soprano MICHAEL LOWE, Lute STEPHEN CLARKE, Organ STEPHEN WILSON, Cello SUNDAY AFTERNOON, OCTOBER 3, 1982, AT 4:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM In order to maintain continuity, the audience is requested to applaud only between groups of pieces. Lieto godea ............................................. GIOVANNI GABRIELI Udite chiari et generosi figli .................................... G. GABRIELI (c. 1553/56-1612) The work of Giovanni Gabrieli, nephew of the organist-composer Andrea Gabrieli, marks the highest point in Venetian music of the late Renaissance. Encouraged by the internal architecture of St. Mark's in Venice, with its two organ galleries, Gabrieli cultivated a style of polychoral writing peculiar to that city in the closing years of the sixteenth century. Characteristic of this style arc the lilting triple-time passages, the sonorous combination of two or more choirs, and the rapid tossing to and fro between choirs of answering phrases, and these features find their way equally into Gabricli's secular vocal writing. Lieto godea, first published in 1587, is an eight-voice madrigal for double choir. In common with the majority of Gabrieli's other madrigals, this work is predominantly diatonic and makes use of conventional word-painting as, for instance, the canon at the word 'fugge' to depict the lover's flight from Cupid's arrows. Somewhat unusual for a madrigal, though, are the striking 'battaglia' rhythms, which suggest instrumental rather than vocal writing. Udite chiari e generosi figli, a more substantial work, is slightly later in date, most probably having been written around 1600 since its text, a dialogue between Tritons and Sirens, makes passing reference to the advent of a new age.