A 16Th-Century Meeting of England & Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HCS Full Repertoire

Season date composer piece soloists Orchestra and location Conductor and any instrumentalists additional choirs 1938/39 Rehearsals only Ursula Nettleship 1939/40 23rd March 1940 Handel Messiah Winifred Bury, Haileybury College Haileybury Combined choirs inc. Mervyn Saunders, Orchestra HCS Ifor Hughes, Eric Bravington (trumpet) Dr Reginald Johnson, Haileybury 1940/41 22nd March 1941 Coleridge-Taylor Hiawatha's Wedding Feast Haileybury HCS and Haileybury College Choir 10th May 1941 Brahms How lovely is thy dwelling Hertford Orchestra Shire Hall Frank Greenfield place Pinsuti A Spring Song arr. Greenfield There is a lady sweet and kind Stanford The Blue Bird Corydon, Arise! 1940/41 July 1941 Repertoire unknown Bishops Stortford Frank Greenfield Music Festival 1942/43 12th December Brahms The Serenade Hertford Orchestra Shire Hall, Hector McCurrach 1942 Hertford Stanford The Revenge Weelkes Like two proud armies 27th May 1943 Handel Messiah Margaret Field-Hyde Leader: Dorothy Loynes W All Saints' Reginald Jacques (soprano), Eileen J Comley (organ) Church, Hertford (combined choirs of Pilcher (alto), Peter Hector McCurrach Broxbourne, Pears (tenor), Henry (continuo) Cheshunt, Hertford, Cummings, bass) Hertford Free Churches, Haileybury, Much Hadham, Thundridge, Ware) 1943/44 Date unknown Haydn The Creation unknown unknown Hertford Music Club concert with Hertford and other choirs 1944/45 7th December Bach Christmas Oratorio Kathleen Willson Orchestra of wood wind Hertford Grammar Hector McCurrach 1944 (contralto), Elster and strings School -

To Download Press

BIO - GRAPHY Tapestry Tapestry made its debut in Jordan Hall with a performance of Steve Reich’s Cristi Catt, soprano, has performed with Tehillim, deemed “a knockout” by The Boston Globe. The trademark of the leading early music groups including En- Boston-based vocal ensemble is combining medieval repertory and contem- semble PAN, Revels, Boston Camerata porary compositions in bold, conceptual programming. Critics hail their rich and La Donna Musicale. Her interest in the distinctive voices, their “technically spot-on singing” and their emotionally meeting points between medieval and folk charged performances. The LA Times writes “They sing beautifully separately traditions has led to research grants to Por- and together with a glistening tone and precise intonation” and The Cleve- tugal and France, and performances with land Plain Dealer describes Tapestry as “an ensemble that plants haunting HourGlass, Le Bon Vent, Blue Thread, and vibrations, old and new, in our ears.” Most recently, Tapestry has expanded their repertoire to include works of impression- ists including Debussy, Lili Boulanger and Vaughan Williams for a US tour in celebra- tion of the 100-year anniversary of World War One Armistice, culminating with a per- formance at the National Gallery in Wash- ington DC. Their newest program, Beyond Borders, builds on their impressionistic discoveries and expands to works of Duke Ellington, Samuel Barber, and Leonard Ber- nstein programmed with early music and folk songs. Concert appearances include the Utrecht Early Music and -

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

SIR PETER MAXWELL DAVIES: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1955: “Burchiello” for sixteen percussion instruments “Opus Clavicembalisticum(Sorabji)” for orchestra “Work on a Theme by Thomas Tompkins” for orchestra 1957: St. Michael”-Sonata for seventeen wind instruments, op.6: 17 minutes 1958: “Prolation” for orchestra, op.8: 20 minutes 1959: “Five Canons” for school/amateur orchestra “Pavan and Galliard” for school/amateur orchestra “Variations on a Theme for Chords” for school/amateur orchestra 1959/76: Five Klee Pictures for orchestra, op.12: 10 minutes + (Collins cd) 1960: Three Pieces for junior orchestra 1961: Fantasy on the National Anthem for school/amateur orchestra 1962: First Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op.19: 11 minutes Sinfonia for chamber orchestra, op. 20: 23 minutes + Regis d) 1963: “Veni Sancte Spiritus” for soprano, contralto, tenor, baritone, chorus and orchestra, op.22: 20 minutes 1964: Second Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op. 23: 39 minutes + (Decca cd) 1967: Songs to Words by Dante for baritone and small orchestra 1969: Foxtrot “St. Thomas Wake” for orchestra, op.37: 20 minutes + (Naxos cd) Motet “Worldes Bliss” for orchestra, op.38: 37 minutes 1971: Suite from “The Boyfriend” for small orchestra, op.50b: 26 minutes * + (Collins cd) 1972: “Walton Tribute” for orchestra Masque “Blind Man’s Buff” for soprano or treble, mezzo-soprano, mime and small orchestra, op.51: 20 minutes 1973: “Stone Liturgy-Runes from a House of the Dead” for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, -

Download Recording Booklet

Johann Sebastian Bach EDITION: BREITKOPF & HÄRTEL, EDITED BY J. RIFKIN (2006) Dunedin Consort & Players John Butt director SUSAN HAMILTON soprano CECILIA OSMOND soprano MARGOT OITZINGER alto THOMAS HOBBS tenor MATTHEW BROOK bass MASS IN J S Bach (1685-1750) Mass in B minor BWV 232 B MINOR Mass in B minor Edition: Breitkopf & Härtel, edited by Joshua Rifkin (2006) Johann Sebastian Bach Dunedin Consort & Players John Butt director ach’s Mass in B Minor is undoubtedly his most spectacular choral work. BIts combination of sizzling choruses and solo numbers covering the gamut of late-Baroque vocal expression render it one of the most joyous musical 6 Et resurrexit ............................................................... 4.02 Missa (Kyrie & Gloria) experiences in the western tradition. Nevertheless, its identity is teased by 7 Et in Spiritum sanctum ................................. 5.27 countless contradictions: it appears to cover the entire Ordinary of the Catholic 1 Kyrie eleison .............................................................. 9.39 8 Confiteor ....................................................................... 3.40 Liturgy, but in Bach’s Lutheran environment the complete Latin text was seldom 2 Christe eleison ........................................................ 4.33 9 Et expecto .................................................................... 2.07 sung as a whole; it seems to have the characteristics of a unified work, yet its 3 Kyrie eleison ............................................................. -

Membra Jesu Nostri

Diskothek: Dietrich Buxtehude: Membra Jesu Nostri Montag, 26. März 2018 20.00 - 22.00 Uhr, SRF 2 Kultur Samstag, 31. März 2018 14.00 - 16.00 Uhr, SRF 2 Kultur (Zweitsendung) Gäste im Studio: Julia Schröder (Geigerin) und Jean-Christophe Groffe (Sänger). Gastgeberin: Jenny Berg Das Resultat Aufnahmen mit Werken aus der Barockzeit zeigen oft grosse Unterschiede, da die Barockmusik den Interpretinnen und Interpreten viele Freiheiten lässt. So ist es auch bei Dietrich Buxtehudes «Membra Jesu nostri»: Es gibt chorische und solistische Besetzungen, unterschiedlich gestimmte Instrumente, italienische und lateinische Textaussprache bei diesen fünf Aufnahmen – und es gibt noch etliche weitere Interpretationen auf dem CD-Markt. In Runde eins wird die Tempowahl zum Ausschlusskriterium: René Jacobs mit dem Concerto Vocale Gent (A3) geht die Beschreibung der Körperteile Jesu zu sportlich an, das Bach Collegium Japan mit Dirigent Masaaki Suzuki (A4) schwankt zu stark im Tempo – eine vergleichsweise gute, aber auch gewöhnliche Interpretation, fanden die beiden Gäste. In der zweiten Runde scheidet das Purcell Quartett (A5) aus – eine Aufnahme mit ausgezeichneten Sängern, dafür aber mit einer recht schlichten Gestaltung des Basso continuo. Am Schluss gibt es einen klaren Sieger: Obwohl Cantus Cölln mit Konrad Junghänel (A1) immer wieder für Gänsehaut sorgt, den Text bewusst ausgestaltet und sehr rhythmisch agiert, überzeugt über alle drei Runden die Aufnahme mit Ton Koopmann und dem Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir) am meisten (A2). Er hat das Werk mehrfach aufgenommen, dies hier ist die zweite Einspielung: Eine sehr lebendige Aufnahme, die ins Innere geht, die die Stimmungen bewusst einsetzt, um die harmonischen Bewegungen zu schärfen, und dabei elegant und historisch informiert verziert. -

Monteverdi: Vespers of 1610

MONTEVERDI: VESPERS OF 1610 Monday 7 March 2016, 7.30pm London Concert Choir with Soloists and QuintEssential Conductor: Mark Forkgen Programme: £2 Welcome to St John’s Smith Square • In accordance with the requirements of Westminster City Council, persons shall not be permitted to sit or stand in any gangway. • The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment is strictly forbidden without formal consent from St John’s Smith Square. • Smoking is not permitted anywhere in St John’s Smith Square. • Refreshments are permitted only in The Footstool Restaurant (our café & restaurant in the crypt). • Please ensure that all digital watch alarms, pagers and mobile phones are switched off. • The Footstool Restaurant will serve interval and post-concert refreshments. · Programme note © Sabine Köllmann Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie London Concert Choir - A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and registered charity number 1057242 Registered Office7 Ildersly Grove, Dulwich, London SE21 8EU St John’s Smith Square, London SW1P 3HA Box Office 020 7222 1061 www.sjss.org.uk St John’s Smith Square Charitable Trust, registered charity no: 1045390. Registered in England. Company no: 3028678. Monday 7 March 2016 St John’s Smith Square MONTEVERDI: VESPERS OF 1610 Mark Forkgen Conductor Rachel Elliott and Rebecca Outram Soprano Nicholas Pritchard and Bradley Smith Tenor Giles Underwood and Colin Campbell Bass London Concert Choir QuintEssential ensemble There will be an INTERVAL of 20 minutes Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) VESPERS OF 1610 (Vespro della Beata Vergine, 1610) THE COMPOSER In the history of Western music Claudio Monteverdi occupies an important position at the threshold between Renaissance and Baroque, and his Vespers of 1610, as the compilation of music for the evening service on Marian feast days is often referred to, represents a milestone in the development of modern music. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

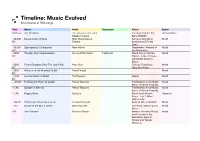

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Programme Information

Programme information Saturday 18th April to Friday 24th April 2020 WEEK 17 THE FULL WORKS CONCERT: CELEBRATING HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN’S BIRTHDAY Tuesday 21st April, 8pm to 10pm Jane Jones honours a very special birthday, as Queen Elizabeth II turns 94 years old. We hear from several different Masters of the Queen’s (or King’s) Music, from William Boyce who presided during the reign of King George II, to Judith Weir who was appointed the very first female Master of the Queen’s Music in 2014. The Central Band of the Royal Air Force also plays Nigel Hess’ Lochnagar Suite, inspired by Prince Charles’ book The Old Man of Lochnagar. Her Majesty has also supported classical music throughout her inauguration of The Queen’s Music Medal which is presented annually to an “outstanding individual or group of musicians who have had a major influence on the musical life of the nation”. Tonight, we hear from the 2016 recipient, Nicola Benedetti, who plays Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending. Classic FM is available across the UK on 100-102 FM, DAB digital radio and TV, at ClassicFM.com, and on the Classic FM and Global Player apps. 1 WEEK 17 SATURDAY 18TH APRIL 3pm to 5pm: MOIRA STUART’S HALL OF FAME CONCERT Over Easter weekend, the new Classic FM Hall of Fame was revealed and this afternoon, Moira Stuart begins her first Hall of Fame Concert since the countdown with the snowy mountains in Sibelius’ Finlandia, which fell to its lowest ever position this year, before a whimsically spooky dance by Saint-Saens. -

The English Concert – Biography

The English Concert – Biography The English Concert is one of Europe’s leading chamber orchestras specialising in historically informed performance. Created by Trevor Pinnock in 1973, the orchestra appointed Harry Bicket as its Artistic Director in 2007. Bicket is renowned for his work with singers and vocal collaborators, including in recent seasons Lucy Crowe, Elizabeth Watts, Sarah Connolly, Joyce DiDonato, Alice Coote and Iestyn Davies. The English Concert has a wide touring brief and the 2014-15 season will see them appear both across the UK and abroad. Recent highlights include European and US tours with Alice Coote, Joyce DiDonato, David Daniels and Andreas Scholl as well as the orchestra’s first tour to mainland China. Harry Bicket directed The English Concert and Choir in Bach’s Mass in B Minor at the 2012 Leipzig Bachfest and later that year at the BBC proms, a performance that was televised for BBC4. Following the success of Handel’s Radamisto in New York 2013, Carnegie Hall has commissioned one Handel opera each season from The English Concert. Theodora followed in early 2014, which toured West Coast of the USA as well as the Théâtre des Champs Elysées Paris and the Barbican London followed by a critically acclaimed tour of Alcina in October 2014. Future seasons will see performances of Handel’s Hercules and Orlando. The English Concert’s discography includes more than 100 recordings with Trevor Pinnock for Deutsche Grammophon Archiv, and a series of critically acclaimed CDs for Harmonia Mundi with violinist Andrew Manze. Recordings with Harry Bicket have been widely praised, including Lucy Crowe’s debut solo recital, Il caro Sassone. -

PMMS Josquin Des Prez Discography June 2021

Josquin des Prez Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of Josquin des Prez (Josquin Lebloitte dit des Prez), who has been indexed as Josquin Desprez, Des Près, and Pres, adopts the format of the Du Fay discography previously posted on this website. It may be noted that at least three book titles since 2000 have named him simply “Josquin,” bypassing the spelling problem. Acknowledgment is due to Pierre-F. Roberge and Todd McComb for an exhaustive list of records containing Josquin’s music in www.medieval.org/emfaq. It incorporates listings from the work of Sydney Robinson Charles in Josquin des Prez: A Guide to Research (Garland Composer Resource Manuals, 1983) and Peter Urquhart in The Josquin Companion (ed. Richard Sherr, Oxford, 2000), which continued where Charles left off. The last two lists each included a title index. This work has also used the following publications already incorporated in the three cited discographies. The 78rpm and early LP eras were covered in discographic format by The Gramophone Shop Encyclopedia of Recorded Music (three editions, 1936, 1942, 1948) and The World’s Encyclopaedia of Recorded Music (three volumes, 1952, 1953, 1957). James Coover and Richard Colvig compiled Medieval and Renaissance Music on Long-Playing Records in two volumes (1964 and 1973), and Trevor Croucher compiled Early Music Discography from Plainsong to the Sons of Bach (Oryx Press, 1981). The Index to Record Reviews compiled by Kurtz Myers (G. K. Hall, 1978) provided useful information. Michael Gray’s classical-discography.org has furnished many details. David Fallows offered many valuable suggestions. -

Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707) Membra Jesu Nostri

Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707) Membra Jesu Nostri Tanya Aspelmeier, Stéphanie Révidat, Salomé Haller, sopranos Rolf Ehlers, haute-contre Julian Prégardien, ténor Benoît Arnould, basse LA CHAPE ll E RHÉNANE LA MAÎT R ISE DE GA R ÇONS DE CO lm A R DIRECTION : ARLETTE STEYER DIRECTION : BENOÎT HA LLER 1 Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707) Membra Jesu Nostri 1 Ad pedes - Ecce super montes 7’40 2 Ad genua - Ad ubera portabimini 9’50 3 Ad manus - Quid sunt plagae istae 9’06 4 Ad latus - Surge amica mea 9’13 5 Ad pectus - Sicut modo geniti infantes 9’27 6 Ad cor - Vulnerasti cor meum 9’03 7 Ad faciem - Illustra faciem tuam 6’16 > minutage total : 60’35 2 LA CHAPE ll E RHÉNANE Tanya Aspelmeier(6), Stéphanie Révidat(1,7), Salomé Haller(1,5,7) Sopranos Rolf Ehlers Haute-contre Julian Prégardien Ténor Benoît Arnould Basse Cosimo Stawiarski, Isabel Schau Violons Sergio Alvarez, Barbara Leitherer, François-Joubert Caillet, Anne-Garance Fabre-Garrus Violes de gambe Armin Bereuter Violone en sol Élodie Peudepièce Violone en ré Jennifer Harris Basson Thomas Boysen Théorbe Marie Bournisien Harpe Sébastien Wonner Orgue et Clavecin LA MAÎT R ISE DE GA R ÇONS DE CO lm A R DIRECTION : ARLETTE STEYER DI R E C TION : BENOÎT HA ll E R 3 Pour le présent enregistrement La Maîtrise de Garçons de Colmar était composée de : Les garçons Sopranos : ARMSPACH-YOUNG Thomas - BARTH François - DIESEL Noé - DROTHIERE Valentin - PAULUS Loïc SCHIELE Jean-Baptiste - SCHMITT Elliott - WEYMANN Vincent Mezzo-sopranos : BUCHER Romain - DECHRISTE Gauthier - GLEYZE Tom - GRAVRAND Dorian