Tallis's Spem in Alium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janet Cardiff

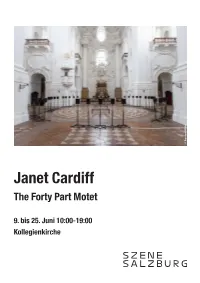

© Bernhard Müller Janet Cardiff The Forty Part Motet 9. bis 25. Juni 10:00-19:00 Kollegienkirche Janet Cardiff The Forty Part Motet Eine Bearbeitung von Spem in Alium Nunquam Habui, 1573 von Thomas Tallis Die kanadische Künstlerin Janet Cardiff hat Die in British Columbia lebende Janet Forty Part Motet wurde ursprünglich produziert mit ihrem international gefeierten Projekt Cardiff entwickelt, meist zusammen mit von Field Art Projects . The Forty Part Motet eine der emotionals- George Bures Miller, seit Jahren Installatio- In Kooperation mit: Arts Council of England, Cana- ten und poetischsten Klanginstallation der nen, Audio- und Video-Walks, die regelmä- da House, Salisbury Festival and Salisbury Cathedral letzten Jahre geschaffen. Die Sommersze- ßig mit Preisen ausgezeichnet werden. Ihre Choir, Baltic Gateshead, The New Art Galerie Walsall, ne 2021 bringt dieses berührende Hörerleb- Einzelausstellungen, die zwischen Wien Now Festival Nottingham nis erstmals nach Salzburg und installiert es und Washington zu sehen waren, sind Er- Gesungen von: Salisbury Cathedral Choir im sakralen Raum der Kollegienkirche. lebnisse für alle Sinne. The Forty Part Mo- Aufnahme & Postproduction: SoundMoves Die Grundlage der Arbeit bildet ein 40-stim- tet hat bereits Besucher*innen von der Tate Editiert von: Georges Bures Miller miges Chorstück, das aus vierzig Lautspre- Gallery bis zum MOMA begeistert. Eine Produktion von: Field Art Projects chern, die kreisförmig angeordnet sind, ab- gespielt wird. Janet Cardiff hat die Stimmen „While listening to a concert you are nor- Mit Unterstützung von der Motette Spem in Alium des englischen mally seated in front of the choir, in tradi- Renaissance-Komponisten Thomas Tallis tional audience position. (…) Enabling the aus dem 16. -

Pieter-Jan Belder the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book

95308 Fitzwilliam VB vol5 2CD_BL1_. 30/09/2016 11:06 Page 1 95308 The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book Volume 5 Munday · Richardson · Tallis Morley · Tomkins · Hooper Pieter-Jan Belder The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book Volume 5 Compact Disc 1 65’42 Compact Disc 2 58’02 John Munday 1555–1630 Anonymous Thomas Morley 1557 –1602 Anonymous & 1 Munday’s Joy 1’26 18 Alman XX 1’58 1 Alman CLII 1’33 Edmund Hooper 1553 –1621 2 Fantasia III, ( fair weather… ) 3’34 19 Praeludium XXII 0’54 2 Pavan CLXIX 5’48 12 Pakington’s Pownde CLXXVIII 2’14 3 Fantasia II 3’36 3 Galliard CLXX 3’00 13 The Irishe Dumpe CLXXIX 1’24 4 Goe from my window (Morley) 4’46 Thomas Tallis c.1505 –1585 4 Nancie XII 4’41 14 The King’s Morisco CCXLVII 1’07 5 Robin 2’08 20 Felix namque I, CIX 9’08 5 Pavan CLIII 5’47 15 A Toye CCLXIII 0’59 6 Galiard CLIV 2’28 16 Dalling Alman CCLXXXVIII 1’16 Ferdinando Richardson 1558 –1618 Anonymous 7 Morley Fantasia CXXIV 5’37 17 Watkins Ale CLXXX 0’57 6 Pavana IV 2’44 21 Praeludium ‘El. Kiderminster’ XXIII 1’09 8 La Volta (set by Byrd) CLIX 1’23 18 Coranto CCXXI 1’18 7 Variatio V 2’47 19 Alman (Hooper) CCXXII 1’13 8 Galiarda VI 1’43 Thomas Tallis Thomas Tomkins 1572 –1656 20 Corrãto CCXXIII 0’55 9 Variatio VII 1’58 22 Felix Namque II, CX 10’16 9 Worster Braules CCVII 1’25 21 Corranto CCXXIV 0’36 10 Pavana CXXIII 6’53 22 Corrãto CCXXV 1’15 Anonymous Anonymous 11 The Hunting Galliard CXXXII 1’59 23 Corrãto CCXXVI 1’08 10 Muscadin XIX 0’41 23 Can shee (excuse) CLXXXVIII 1’48 24 Alman CCXXVII 1’41 11 Pavana M.S. -

Download Booklet

Surround Sound SACDCD 9 Thomas Tallis CORO Sing and glorify According to the 17th-century witness who recounts the origins in the early 1570s of Spem in alium (track 1), Tallis’s 40-part motet was later revived ‘at the prince’s coronation’. By that, he must mean the investiture of Henry, James I’s eldest son, as Prince of Wales on 4 June 1610. By a happy coincidence, another source adds independent confirmation. It states that, following the investiture ceremony itself, the newly crowned prince dined in state at Whitehall to the sound of ‘music of forty several parts’. Clearly the new words that have been applied to Tallis’s music were written specially for the investiture, for they celebrate the ‘holy day’ in which Henry, ‘princely and mighty’, has been elevated by his new ‘creation’. At an event such as this, instruments would have joined voices to produce as rich and spectacular a sound as possible. In this recorded performance, we attempt to simulate that grandly sonorous noise. Thomas Tallis Sing and glorify heaven’s high majesty, for ever give it greeting, love and joy, Author of this blessed harmony. heart and voice meeting. Spem Sound divine praises with melodious graces. Live Henry, princely and mighty! This is the day, holy day, happy day; Henry live in thy creation happy! G IBBONS John Milsom ©2003 in alium B YRD Producer: Mark Brown The Sixteen Ltd., General Manager, Alison Stillman Music for Monarchs Engineer: Mike Hatch The Sixteen Productions Ltd., General Manager, Claire Long T OMKINS Digital mastering: Floating Earth www.thesixteen.com Organ Tuning: Keith McGowan For further information about The Sixteen and Magnates Recorded in May 2003 in All Saints Church, recordings on CORO or live performances Tooting, London and tours, call +44 (0) 1869 331 711, Design: Richard Boxall Design Associates or email [email protected]. -

HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for Cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009

CORO CORO HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009 “Overall, this disc ranks as The Sixteen’s most exciting achievement in its impressive Handel discography.” HANDEL gramophone Choruses HANDEL: Dixit Dominus cor16076 STEFFANI: Stabat Mater The Sixteen adds to its stunning Handel collection with a new recording of Dixit Dominus set alongside a little-known treasure – Agostino Steffani’s Stabat Mater. THE HANDEL COLLECTION cor16080 Eight of The Sixteen’s celebrated Handel recordings in one stylish boxed set. The Sixteen To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit HARRY CHRISTOPHERS www.thesixteen.com cor16180 He is quite simply the master of chorus and on this compilation there is much rejoicing. Right from the outset, a chorus of Philistines revel in Awake the trumpet’s lofty sound to celebrate Dagon’s festival in Samson; the Israelites triumph in their victory over Goliath with great pageantry in How excellent Thy name from Saul and we can all feel the exuberance of I will sing unto the Lord from Israel in Egypt. There are, of course, two Handel oratorios where the choruses dominate – Messiah and Israel in Egypt – and we have given you a taster of pure majesty in the Amen chorus from Messiah as well as the Photograph: Marco Borggreve Marco Photograph: dramatic ferocity of He smote all the first-born of Egypt from Israel in Egypt. Handel is all about drama; even though he forsook opera for oratorio, his innate sense of the theatrical did not leave him. Just listen to the poignancy of the opening of Act 2 from Acis and Galatea where the chorus pronounce the gloomy prospect of the lovers and the impending appearance of the monster Polyphemus; and the torment which the Israelites create in O God, behold our sore distress when Jephtha commands them to “invoke the holy name of Israel’s God”– it’s surely one of his greatest fugal choruses. -

The English Anthem Project the Past Century and a Half, St

Special thanks to St. John’s staff for their help with promotions and program printing: Mair Alsgaard, Organist; Charlotte Jacqmain, Parish Secretary; and Ministry Coordinator, Carol The Rev. Ken Hitch, Rector Sullivan. Thanks also to Tim and Gloria Stark for their help in preparing the performance and reception spaces. To commemorate the first Episcopal worship service in Midland, MI 150 years ago, and in appreciation for community support over The English Anthem Project the past century and a half, St. John's and Holy Family Episcopal Churches are "Celebrating In Community" with 16th and 17th Centuries events like today’s concert. We hope you are able to share in future sesquicentennial celebration events we have planned for later this summer: www.sjec-midland.org/150 Exultate Deo Chamber Choir Weekly Worship Schedule SUNDAYS Saturday, June 24, 2017 8:00 AM - Holy Eucharist Traditional Worship, Spoken Service 4:00 p.m. 10:00 AM - Holy Eucharist Traditional Worship with Music, St. John’s Episcopal Church Nursery, Children's Ministry 405 N. Saginaw Road WEDNESDAYS Midland, MI 48640 12:00 PM - Holy Eucharist Quiet, Contemplative Worship 405 N. Saginaw Rd / Midland, MI 48640 This concert is offered as one of (989) 631-2260 / [email protected] several ‘Celebrating in Community’ www.sjec-midland.org events marking 150 years of All 8 Are Welcome. The Episcopal Church in Midland, MI The English Anthem Project William Byrd (c1540-1623) worked first in Lincoln Cathedral then became a member of the Chapel Royal, where for a time he and Tallis 16th and 17th Centuries were joint organists. -

Extract from Text

DISCOVER CHORAL MUSIC Contents page Track List 4 A Brief History of Choral Music , by David Hansell 13 I. Origins 14 II. Early Polyphony 20 III. The Baroque Period 39 IV. The Classical Period 68 V. The Nineteenth Century 76 VI. The Twentieth Century and Beyond 99 Five Centuries of Choral Music: A Timeline (choral music, history, art and architecture, literature) 124 Glossary 170 Credits 176 3 DISCOVER CHORAL MUSIC Track List CD 1 Anon (Gregorian Chant) 1 Crux fidelis 0.50 Nova Schola Gregoriana / Alberto Turco 8.550952 Josquin des Prez (c. 1440/55–c. 1521) 2 Ave Maria gratia plena 5.31 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.553428 John Taverner (c. 1490–1545) Missa ‘Gloria Tibi Trinitas’ 3 Sanctus (extract) 5.28 The Sixteen / Harry Christophers CDH55052 John Taverner 4 Christe Jesu, pastor bone 3.35 Cambridge Singers / John Rutter COLCD113 4 DISCOVER CHORAL MUSIC Thomas Tallis (c. 1505–1585) 5 In manus tuas, Domine 2.36 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.550576 William Byrd (c. 1540–1623) 6 Laudibus in sanctis 5.47 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.550843 Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525/6–1594) Missa ‘Aeterna Christi Munera’ 7 Agnus Dei 4.58 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.550573 Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548–1611) 8 O magnum mysterium 4.17 Oxford Camerata / Jeremy Summerly 8.550575 Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) Vespers of the Blessed Virgin 9 Laudate pueri Dominum 6.05 The Scholars Baroque Ensemble 8.550662–63 Giacomo Carissimi (1605–1674) Jonas 10 Recitative: ‘Et crediderunt Ninevitae…’ 0.25 11 Chorus of Ninevites: ‘Peccavimus, -

Universiv Micrmlms Internationcil

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microHlming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify m " '<ings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyriglited materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin film ing at the upper le ft hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections w ith small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Programme Information

Programme information Saturday 18th April to Friday 24th April 2020 WEEK 17 THE FULL WORKS CONCERT: CELEBRATING HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN’S BIRTHDAY Tuesday 21st April, 8pm to 10pm Jane Jones honours a very special birthday, as Queen Elizabeth II turns 94 years old. We hear from several different Masters of the Queen’s (or King’s) Music, from William Boyce who presided during the reign of King George II, to Judith Weir who was appointed the very first female Master of the Queen’s Music in 2014. The Central Band of the Royal Air Force also plays Nigel Hess’ Lochnagar Suite, inspired by Prince Charles’ book The Old Man of Lochnagar. Her Majesty has also supported classical music throughout her inauguration of The Queen’s Music Medal which is presented annually to an “outstanding individual or group of musicians who have had a major influence on the musical life of the nation”. Tonight, we hear from the 2016 recipient, Nicola Benedetti, who plays Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending. Classic FM is available across the UK on 100-102 FM, DAB digital radio and TV, at ClassicFM.com, and on the Classic FM and Global Player apps. 1 WEEK 17 SATURDAY 18TH APRIL 3pm to 5pm: MOIRA STUART’S HALL OF FAME CONCERT Over Easter weekend, the new Classic FM Hall of Fame was revealed and this afternoon, Moira Stuart begins her first Hall of Fame Concert since the countdown with the snowy mountains in Sibelius’ Finlandia, which fell to its lowest ever position this year, before a whimsically spooky dance by Saint-Saens. -

Central Reference CD List

Central Reference CD List January 2017 AUTHOR TITLE McDermott, Lydia Afrikaans Mandela, Nelson, 1918-2013 Nelson Mandela’s favorite African folktales Warnasch, Christopher Easy English [basic English for speakers of all languages] Easy English vocabulary Raifsnider, Barbara Fluent English Williams, Steve Basic German Goulding, Sylvia 15-minute German learn German in just 15 minutes a day Martin, Sigrid-B German [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Dutch in 60 minutes Dutch [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Swedish in 60 minutes Berlitz Danish in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian phrase book & CD McNab, Rosi Basic French Lemoine, Caroline 15-minute French learn French in just 15 minutes a day Campbell, Harry Speak French Di Stefano, Anna Basic Italian Logi, Francesca 15-minute Italian learn Italian in just 15 minutes a day Cisneros, Isabel Latin-American Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Latin American Spanish in 60 minutes Martin, Rosa Maria Basic Spanish Cisneros, Isabel Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Spanish for travelers Spanish for travelers Campbell, Harry Speak Spanish Allen, Maria Fernanda S. Portuguese [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Portuguese in 60 minutes Sharpley, G.D.A. Beginner’s Latin Economides, Athena Collins easy learning Greek Garoufalia, Hara Greek conversation Berlitz Greek in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi travel pack Bhatt, Sunil Kumar Hindi : a complete course for beginners Pendar, Nick Farsi : a complete course for beginners -

ÄÁŒ @˧7'Ƚ“¾¢É˚Há©ÈÈ9

557864bk Philips US 11/7/06 3:05 pm Page 4 Elizabeth Farr Peter Elizabeth Farr specialises in the performance of keyboard music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. She has performed solo recitals on the harpsichord, organ, and pedal harpsichord to critical acclaim throughout the United States and in Germany. Her PHILIPS performances as a collaborative artist, concerto soloist, and basso-continuo player have (1560/61–1628) also earned high praise. Her recording of Elisabeth-Claude Jacquet de La Guerre’s Suites Nos. 1-6 for Harpsichord (Naxos 8.557654-55) was awarded the Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik, Bestenliste 1/2006. Elizabeth Farr holds degrees in harpsichord and organ performance from Stetson University, the Juilliard School, and Harpsichord Works the University of Michigan, having studied with Paul Jenkins, Vernon de Tar, and Edward Parmentier. Currently she is on the faculty of the University of Colorado where Fantasia in F • Bonjour mon cœur • Io partirò she teaches harpsichord and organ, conducts the Early Music Ensemble, and offers classes in performance practices and basso-continuo playing. Elizabeth Farr The Harpsichord Jerome de Zentis was a consummate musical instrument-maker. He built instruments first in Rome, then in Florence for the Medici family, London as the ‘King’s Virginal Maker’, Stockholm as the instrument-maker to the court, Viterbo for the Pope, and finally in Paris for the King of France. The instrument used in this recording is one he made upon his return to Italy after ten years in Sweden as the instrument-maker royal to Queen Christina. This instrument is unusual because it is clearly an Italian instrument, but appears to have been made by a North German maker, or at least an Italian maker who was fully informed of the Northern European harpsichord-making practices and materials. -

Motive and Spatialization in Thomas Tallis' Spem in Alium Kevin Davis

Motive and Spatialization in Thomas Tallis’ Spem in Alium Kevin Davis Abstract This paper is an analysis of Thomas Tallis’ 40-voice motet Spem in Alium. A piece of this scale and complexity posed challenges in terms of voice leading and counterpoint in this musical style due to its forces, scale, and complexity. In this analysis I suggest that Spem in Alium, due to the peculiarities of its nature, compelled Tallis to experiment with two specific elements—motive and spatialization, the specific treatment of which arises from the fundamental properties counterpoint and voice-leading and combines to create this unique form of antiphonal music. From this combination of factors, the piece’s distinctive “polyphonic detailism” emerges. 1 Origins of work and project Suggestions as to how and why such a work came to be are varied and unreliable. In her book Thomas Tallis and His Music in Victorian England, Suzanne Cole lists a variety of possible reasons claimed by different writers: an attempt to improve upon a 36-voice work of Ockeghem, for quasi-political reasons, as a response to a royal payment of 40 pounds, as a protest on behalf of forty generations of English Catholics slandered by the Protestant Reformation, and for Elizabeth I’s 40th birthday celebration2. Paul Doe in his book Tallis also suggests that is might have been for the sake of personal fulfillment, though as a sole motivation seems less likely.3 Thomas Legge in his preface to the score makes the most convincing argument as to its origin however: inspired by a performance of mass of 40 voices by Alessandro Striggio in London, June of 1557, Tallis was encouraged to undertake the challenge of composing a work with similar forces.