Motive and Spatialization in Thomas Tallis' Spem in Alium Kevin Davis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

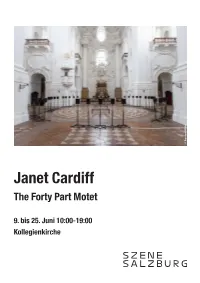

Janet Cardiff

© Bernhard Müller Janet Cardiff The Forty Part Motet 9. bis 25. Juni 10:00-19:00 Kollegienkirche Janet Cardiff The Forty Part Motet Eine Bearbeitung von Spem in Alium Nunquam Habui, 1573 von Thomas Tallis Die kanadische Künstlerin Janet Cardiff hat Die in British Columbia lebende Janet Forty Part Motet wurde ursprünglich produziert mit ihrem international gefeierten Projekt Cardiff entwickelt, meist zusammen mit von Field Art Projects . The Forty Part Motet eine der emotionals- George Bures Miller, seit Jahren Installatio- In Kooperation mit: Arts Council of England, Cana- ten und poetischsten Klanginstallation der nen, Audio- und Video-Walks, die regelmä- da House, Salisbury Festival and Salisbury Cathedral letzten Jahre geschaffen. Die Sommersze- ßig mit Preisen ausgezeichnet werden. Ihre Choir, Baltic Gateshead, The New Art Galerie Walsall, ne 2021 bringt dieses berührende Hörerleb- Einzelausstellungen, die zwischen Wien Now Festival Nottingham nis erstmals nach Salzburg und installiert es und Washington zu sehen waren, sind Er- Gesungen von: Salisbury Cathedral Choir im sakralen Raum der Kollegienkirche. lebnisse für alle Sinne. The Forty Part Mo- Aufnahme & Postproduction: SoundMoves Die Grundlage der Arbeit bildet ein 40-stim- tet hat bereits Besucher*innen von der Tate Editiert von: Georges Bures Miller miges Chorstück, das aus vierzig Lautspre- Gallery bis zum MOMA begeistert. Eine Produktion von: Field Art Projects chern, die kreisförmig angeordnet sind, ab- gespielt wird. Janet Cardiff hat die Stimmen „While listening to a concert you are nor- Mit Unterstützung von der Motette Spem in Alium des englischen mally seated in front of the choir, in tradi- Renaissance-Komponisten Thomas Tallis tional audience position. (…) Enabling the aus dem 16. -

Universiv Micrmlms Internationcil

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microHlming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify m " '<ings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyriglited materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin film ing at the upper le ft hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections w ith small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

ÄÁŒ @˧7'Ƚ“¾¢É˚Há©ÈÈ9

557864bk Philips US 11/7/06 3:05 pm Page 4 Elizabeth Farr Peter Elizabeth Farr specialises in the performance of keyboard music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. She has performed solo recitals on the harpsichord, organ, and pedal harpsichord to critical acclaim throughout the United States and in Germany. Her PHILIPS performances as a collaborative artist, concerto soloist, and basso-continuo player have (1560/61–1628) also earned high praise. Her recording of Elisabeth-Claude Jacquet de La Guerre’s Suites Nos. 1-6 for Harpsichord (Naxos 8.557654-55) was awarded the Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik, Bestenliste 1/2006. Elizabeth Farr holds degrees in harpsichord and organ performance from Stetson University, the Juilliard School, and Harpsichord Works the University of Michigan, having studied with Paul Jenkins, Vernon de Tar, and Edward Parmentier. Currently she is on the faculty of the University of Colorado where Fantasia in F • Bonjour mon cœur • Io partirò she teaches harpsichord and organ, conducts the Early Music Ensemble, and offers classes in performance practices and basso-continuo playing. Elizabeth Farr The Harpsichord Jerome de Zentis was a consummate musical instrument-maker. He built instruments first in Rome, then in Florence for the Medici family, London as the ‘King’s Virginal Maker’, Stockholm as the instrument-maker to the court, Viterbo for the Pope, and finally in Paris for the King of France. The instrument used in this recording is one he made upon his return to Italy after ten years in Sweden as the instrument-maker royal to Queen Christina. This instrument is unusual because it is clearly an Italian instrument, but appears to have been made by a North German maker, or at least an Italian maker who was fully informed of the Northern European harpsichord-making practices and materials. -

Tallis's Spem in Alium

Spem in Alium – a comparatively review of fourteen recordings by Ralph Moore Background We know less about Thomas Tallis than Shakespeare or any other major cultural figure of the Tudor age; definite facts are few and reasonable inferences and conjectures are many, starting even with the dates of his birth – presumed to be around 1505 - and death - either 20th or 23rd November, 1585. The exact site of his grave in the chancel of the parish of St Alfege Church, Greenwich, is lost. We have no authenticated portrait. What we do know is that despite being a recusant Catholic, he not only survived those perilous times but prospered under a succession of Protestant monarchs, the sole Catholic being Edward VII’s sister Mary, who reigned for only five years, from 1553-1558. He was so valued and respected that Elizabeth gave him the lease on a manor house and a handsome income, and in 1575 he and his pupil William Byrd were granted an exclusive royal patent to print and publish polyphonic music. The key to his survival must lie in his discretion, flexibility and, above all, prodigious talent: he is indubitably one of the greatest English composers of his or any age and a towering figure in Renaissance choral music. His masterpiece is certainly the forty-voice motet Spem in alium but here again, verified facts regarding its origin and first performance are few. The original manuscript is lost and our knowledge of the work is derived from another score prepared for the investiture in 1610 of James I’s elder son, Henry, as Prince of Wales, and used again for the coronation in 1625 of his younger brother, Charles I, next in line to the throne after Harry’s death in 1612 from typhoid fever at eighteen years old. -

Newsletter.05

College of L e t t e r s & S c i e n c e U n i v e r s i t y D EPARTMENT o f of California B e r k e l e y MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 5 September 2005 D EAR A LUMNI AND F RIENDS , Note from the Chair reetings to all from the PEOPLE 1–3Update on the last 4 years GUniversity of California, ince the last newsletter, Wye Allanbrook Berkeley, Department of Music, Scompleted her term as department chair, Centenary Celebration this year celebrating our 100th having contributed enormous effort on 100 years of music at Cal birthday! (See article below.) behalf of the new Hargrove Music Library 1, 8–9 This newsletter has always Bonnie Wade building. For the past two years, she has Faculty News Creative accomplishments, been intended as an occasional publication been a Fellow at the National Humanities honors & awards, new to bring to you news of the department. Center in North Carolina. She returns to 4arrivals– Melford6 & Midiyanto For comprehensive details and regular teaching in the 2005–06 academic year. updates please visit our websites: http:// In fall 2003, Allanbrook was succeeded music.berkeley.edu (department); www. by Anthony Newcomb, who served as Gifts to the Department lib.berkeley.edu/MUSI (music library); and department chair for two years. After a 6 www.cnmat.berkeley.edu (Center for New long and distinguished career as teacher Music and Audio Technologies, CNMAT). -

The Tallis Scholars

Friday, April 10, 2015, 8pm First Congregational Church The Tallis Scholars Peter Phillips, director Soprano Alto Tenor Amy Haworth Caroline Trevor Christopher Watson Emma Walshe Clare Wilkinson Simon Wall Emily Atkinson Bass Ruth Provost Tim Scott Whiteley Rob Macdonald PROGRAM Josquin Des Prez (ca. 1450/1455–1521) Gaude virgo Josquin Missa Pange lingua Kyrie Gloria Credo Santus Benedictus Agnus Dei INTERMISSION William Byrd (ca. 1543–1623) Cunctis diebus Nico Muhly (b. 1981) Recordare, domine (2013) Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) Tribute to Caesar (1997) Byrd Diliges dominum Byrd Tribue, domine Cal Performances’ 2014–2015 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 26 CAL PERFORMANCES PROGRAM NOTES he end of all our exploring will be Josquin, who built on the cantus firmus tradi- Tto arrive where we started and know the tion of the 15th century, developing the freer place for the first time.” So writes T. S. Eliot in parody and paraphrase mass techniques. A cel- his Four Quartets, and so it is with tonight’s ebrated example of the latter, the Missa Pange concert. A program of cycles and circles, of Lingua treats its plainsong hymn with great revisions and reinventions, this evening’s flexibility, often quoting more directly from performance finds history repeating in works it at the start of a movement—as we see here from the Renaissance and the present day. in opening soprano line of the Gloria—before Setting the music of William Byrd against moving into much more loosely developmen- Nico Muhly, the expressive beauty of Josquin tal counterpoint. Also of note is the equality of against the ascetic restraint of Arvo Pärt, the imitative (often canonic) vocal lines, and exposes the common musical fabric of two the textural variety Josquin creates with so few ages, exploring the long shadow cast by the voices, only rarely bringing all four together. -

Voice of Fire: Sensory Museum Experiences and Digital Reproduction

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-07-15 Voice of Fire: Sensory Museum Experiences and Digital Reproduction McDougall, Lauren McDougall, L. (2013). Voice of Fire: Sensory Museum Experiences and Digital Reproduction (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28662 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/821 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Voice of Fire: Sensory Museum Experiences and Digital Reproduction by Lauren McDougall A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA JULY, 2013 © Lauren McDougall 2013 ii Abstract The purchase of the painting Voice of Fire by the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) ignited one of Canada’s most heated artistic debates. Focusing on Voice of Fire and the NGC website, this study analyzed how digital reproduction of art on a museum website contributes to a sensory understanding of museum experience. Communicative technologies in the form of websites, social media and high-resolution images have changed spectatorship but continue to be problematic when essential features of the painting are dependent on physical and sensory museum ‘experience’. -

Spem in Alium: the Virtual Choir Project

Spem in Alium: The Virtual Choir Project James Haupt April 28, 2003 - Table of Contents - Section 1 Introduction 1.1 A Brief History and Introduction .................................................................2 1.2 Computers and Digital Music .......................................................................2 1.3 Revival of the Part Book .................................................................................3 Section 2 Spem in Alium 2.1 Digitizing Spem in Alium ................................................................................5 Section 3 The Virtual Choir 3.1 Digitally Creating the Choir ..........................................................................5 3.2 Recording the Choir ........................................................................................6 3.3 Splicing the Notes ...........................................................................................7 Section 4 Looking Ahead 4.1 Future Logistics ...............................................................................................9 4.2 The Performance .............................................................................................9 4.3 Future Applications ......................................................................................10 Section 5 Credits 5.1 Credits .............................................................................................................11 Works Cited...............................................................................................................12 -

The Tallis Scholars Perform Program of Sacred Renaissance Vocal Music in Symphony Center Presents Special Concert at Fourth Presbyterian Church

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: March 21, 2016 Eileen Chambers/CSO, 312-294-3092 Lisa Dell/The Silverman Group, Inc., 312-932-9950 Photos Available By Request [email protected] THE TALLIS SCHOLARS PERFORM PROGRAM OF SACRED RENAISSANCE VOCAL MUSIC IN SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS SPECIAL CONCERT AT FOURTH PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Tuesday, April 5, at 7:30 p.m. CHICAGO—Acclaimed British vocal ensemble The Tallis Scholars, led by the group’s director Peter Phillips, performs a program of sacred Renaissance music in a Symphony Center Presents Special Concert on Tuesday, April 5 at 7:30 p.m. at Fourth Presbyterian Church (126 E. Chestnut Street). The ensemble’s program includes a cappella selections from composers William Byrd, John Taverner, Richard Davy, Thomas Tallis, and Alfonso Ferrabosco. The program includes two motets—Laetentur coeli and Vigilate—by English composer William Byrd, a pupil of Thomas Tallis. Also on the program is John Taverner’s Missa Western Wynde, a setting of sacred text to the tune of a popular Renaissance love song and the free composed choral work Salve Regina by Richard Davy, as well as another setting of the same Marian hymn by William Byrd. The ensemble also performs Thomas Tallis’ Lamentations I, a multilayered musical work that laments not only the biblical fall of Jerusalem, but reflects the sorrow of a Catholic composer living in Queen Elizabeth’s Protestant England. Completing the program is Lamentations, a setting of the same biblical text as the Tallis work by Italian composer Alfonso Ferrabosco. This Renaissance-focused concert program features music composed during Shakespeare’s lifetime and is part of the citywide SHAKESPEARE 400 CHICAGO celebration. -

Alessandro Striggio Mass for 40 and 60 Voices

GCDSA 921623 Alessandro Striggio New release information February 2012 Mass for 40 and 60 voices NOTES (ENG) NOTES (FRA) As his starting point for a brand new recording of C’est à la polychoralité de la Renaissance et au the music from the polychoral Renaissance and « Baroque monumental » que Hervé Niquet dédie the “monumental Baroque”, with Alessandro son nouvel enregistrement, en recréant les Striggio’s 40 and 60-part Missa sopra Ecco sì beato célébrations musicales dans la cathédrale de Santa giorno leading the way, Hervé Niquet turns to the Maria del Fiore à l’occasion d’un jour de fête en musical celebrations for a feast day occasion in l’honneur de Saint-Jean Baptiste : la messe à 40 et the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence 60 voix de Alessandro Striggio, Missa sopra Ecco sì in honour of St John the Baptist, adding a trio of beato giorno, est accompagnée du motet Ecce works by Orazio Benevoli, another specialist in beatem lucem, lui aussi à 40 voix et du même multi-parted choral works, and Striggio’s motet compositeur, et d’un trio d’œuvres de Orazio Benevoli, Ecce beatem lucem, also scored for 40 voices. autre « spécialiste » de la musique chorale « monumentale ». For sessions in Notre-Dame du Liban in Paris, using an edition of the Mass by Dominique Visse, Pour l’enregistrement de l’œuvre à Notre-Dame du originating in 1978, Niquet gathered 60 singers Liban à Paris, basé sur une édition de la Messe Alessandro Striggio (c.1536-1592) (as called for in the Agnus Dei) plus instrumentalists réalisée par Dominique Visse -

Remarks on the Festivities of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Prague (1585)

Musicologica Brunensia 51 / 2016 / 1 DOI: 10.5817/MB2016-1-2 Remarks on the Festivities of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Prague (1585) Jan Baťa / [email protected] Ústav hudební vědy, Filozofická fakulta, Univerzita Karlova, Praha, CZ Abstract The festivities of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Prague and Landshut in June 1585 have already attracted much attention among historians. This article considers the musical part of the celebration that has yet not been discussed in detail. Using extant narrative, iconographi- cal and musical sources, it focuses on the first part of the festivity which took place at Prague Castle. It postulates a hypothesis that the forty-part motet Ecce beatam lucem from the Man- tuan composer and instrumentalist Alessandro Striggio (1536/37–1592) based on the text of German musician and poet Paulus Melissus-Schede (1539–1602) was performed in St. Vitus’ cathedral. Key words Paulus Melissus (1539–1602), Philippe de Monte (1521–1603), motet, multiple-choir music, Or- der of the Golden Fleece, Prague, Renaissance festivities, Alessandro Striggio (1536/37–1592), Ratsschulbibliothek Zwickau 25 Jan Baťa Remarks on the Festivities of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Prague (1585) The Order of the Golden Fleece is one of the most renowned chivalric orders. It was founded in 1430 by Phillip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1397–1467) to cultivate the ideal of Christian chivalry and to maintain the Christian faith. After the extinction of the Burgundian dynasty, the sovereignty of the Order passed to the Habsburg kings of Spain, where it remained until 1700 when the last of the Spanish Habsburgs, Charles II, died. -

Story of Spem in Alium, At

SPEM IN ALIUM Spem in alium numquam habui praeter in te Deus Israel qui irascéris et propitius eris et omnia peccata hominum in tribulatione dimittis. Domine Deus, Creator coeli et terrae, respice humilitatem nostram. Spem in alium is a forty part motet composed by Englishman, Thomas Tallis [c.1505‐ 1585], organist and composer to successive sovereigns throughout the course of the upheavals wrought in England by the Protestant Revolt. This motet ranks with the greatest musical compositions. The text is taken from a paraphrase of words in the Book of Judith where the children of Israel faced slaughter at the hands of the Assyrian general, Holofernes. Hope in any other than Thee I have never had, O God of Israel, whose anger may yet may be appeased as Thou forgivest all the sins man commits in his distress. Lord God, Creator of Heaven and Earth, look upon us in our lowliness. The words appear in a Responsum in the ancient Sarum rite of Mass, predecessor of the Tridentine rite. No passage in the Book of Judith reflects the content of this prayer precisely, but it manifests the recourse to humility and complete trust in God of the heroine before she sets out to relieve the Israelites by bewitching Holofernes with her beauty, watching as he lapses into a drunken stupor, then cuts off his head. There is debate as to when, and for what occasion, Tallis wrote this remarkable work. On the wikipedia website it is said to have been written during Elizabeth’s reign [1558‐1603]. The author of the material there quotes a letter written some 40 years on by one Thomas Wateridge who asserts that an unidentified Duke had incited English composers to improve on a motet heard “in Queene Elizabeth’s time” and written by an Italian, that Tallis wrote the work in consequence and that the Duke rewarded him by placing his own gold chain around Tallis’s neck.