The Mass and Vespers of 1610: the Sources and Their Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universiv Micrmlms Internationcil

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microHlming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify m " '<ings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyriglited materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin film ing at the upper le ft hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections w ith small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

ÄÁŒ @˧7'Ƚ“¾¢É˚Há©ÈÈ9

557864bk Philips US 11/7/06 3:05 pm Page 4 Elizabeth Farr Peter Elizabeth Farr specialises in the performance of keyboard music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. She has performed solo recitals on the harpsichord, organ, and pedal harpsichord to critical acclaim throughout the United States and in Germany. Her PHILIPS performances as a collaborative artist, concerto soloist, and basso-continuo player have (1560/61–1628) also earned high praise. Her recording of Elisabeth-Claude Jacquet de La Guerre’s Suites Nos. 1-6 for Harpsichord (Naxos 8.557654-55) was awarded the Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik, Bestenliste 1/2006. Elizabeth Farr holds degrees in harpsichord and organ performance from Stetson University, the Juilliard School, and Harpsichord Works the University of Michigan, having studied with Paul Jenkins, Vernon de Tar, and Edward Parmentier. Currently she is on the faculty of the University of Colorado where Fantasia in F • Bonjour mon cœur • Io partirò she teaches harpsichord and organ, conducts the Early Music Ensemble, and offers classes in performance practices and basso-continuo playing. Elizabeth Farr The Harpsichord Jerome de Zentis was a consummate musical instrument-maker. He built instruments first in Rome, then in Florence for the Medici family, London as the ‘King’s Virginal Maker’, Stockholm as the instrument-maker to the court, Viterbo for the Pope, and finally in Paris for the King of France. The instrument used in this recording is one he made upon his return to Italy after ten years in Sweden as the instrument-maker royal to Queen Christina. This instrument is unusual because it is clearly an Italian instrument, but appears to have been made by a North German maker, or at least an Italian maker who was fully informed of the Northern European harpsichord-making practices and materials. -

Motive and Spatialization in Thomas Tallis' Spem in Alium Kevin Davis

Motive and Spatialization in Thomas Tallis’ Spem in Alium Kevin Davis Abstract This paper is an analysis of Thomas Tallis’ 40-voice motet Spem in Alium. A piece of this scale and complexity posed challenges in terms of voice leading and counterpoint in this musical style due to its forces, scale, and complexity. In this analysis I suggest that Spem in Alium, due to the peculiarities of its nature, compelled Tallis to experiment with two specific elements—motive and spatialization, the specific treatment of which arises from the fundamental properties counterpoint and voice-leading and combines to create this unique form of antiphonal music. From this combination of factors, the piece’s distinctive “polyphonic detailism” emerges. 1 Origins of work and project Suggestions as to how and why such a work came to be are varied and unreliable. In her book Thomas Tallis and His Music in Victorian England, Suzanne Cole lists a variety of possible reasons claimed by different writers: an attempt to improve upon a 36-voice work of Ockeghem, for quasi-political reasons, as a response to a royal payment of 40 pounds, as a protest on behalf of forty generations of English Catholics slandered by the Protestant Reformation, and for Elizabeth I’s 40th birthday celebration2. Paul Doe in his book Tallis also suggests that is might have been for the sake of personal fulfillment, though as a sole motivation seems less likely.3 Thomas Legge in his preface to the score makes the most convincing argument as to its origin however: inspired by a performance of mass of 40 voices by Alessandro Striggio in London, June of 1557, Tallis was encouraged to undertake the challenge of composing a work with similar forces. -

Tallis's Spem in Alium

Spem in Alium – a comparatively review of fourteen recordings by Ralph Moore Background We know less about Thomas Tallis than Shakespeare or any other major cultural figure of the Tudor age; definite facts are few and reasonable inferences and conjectures are many, starting even with the dates of his birth – presumed to be around 1505 - and death - either 20th or 23rd November, 1585. The exact site of his grave in the chancel of the parish of St Alfege Church, Greenwich, is lost. We have no authenticated portrait. What we do know is that despite being a recusant Catholic, he not only survived those perilous times but prospered under a succession of Protestant monarchs, the sole Catholic being Edward VII’s sister Mary, who reigned for only five years, from 1553-1558. He was so valued and respected that Elizabeth gave him the lease on a manor house and a handsome income, and in 1575 he and his pupil William Byrd were granted an exclusive royal patent to print and publish polyphonic music. The key to his survival must lie in his discretion, flexibility and, above all, prodigious talent: he is indubitably one of the greatest English composers of his or any age and a towering figure in Renaissance choral music. His masterpiece is certainly the forty-voice motet Spem in alium but here again, verified facts regarding its origin and first performance are few. The original manuscript is lost and our knowledge of the work is derived from another score prepared for the investiture in 1610 of James I’s elder son, Henry, as Prince of Wales, and used again for the coronation in 1625 of his younger brother, Charles I, next in line to the throne after Harry’s death in 1612 from typhoid fever at eighteen years old. -

Newsletter.05

College of L e t t e r s & S c i e n c e U n i v e r s i t y D EPARTMENT o f of California B e r k e l e y MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 5 September 2005 D EAR A LUMNI AND F RIENDS , Note from the Chair reetings to all from the PEOPLE 1–3Update on the last 4 years GUniversity of California, ince the last newsletter, Wye Allanbrook Berkeley, Department of Music, Scompleted her term as department chair, Centenary Celebration this year celebrating our 100th having contributed enormous effort on 100 years of music at Cal birthday! (See article below.) behalf of the new Hargrove Music Library 1, 8–9 This newsletter has always Bonnie Wade building. For the past two years, she has Faculty News Creative accomplishments, been intended as an occasional publication been a Fellow at the National Humanities honors & awards, new to bring to you news of the department. Center in North Carolina. She returns to 4arrivals– Melford6 & Midiyanto For comprehensive details and regular teaching in the 2005–06 academic year. updates please visit our websites: http:// In fall 2003, Allanbrook was succeeded music.berkeley.edu (department); www. by Anthony Newcomb, who served as Gifts to the Department lib.berkeley.edu/MUSI (music library); and department chair for two years. After a 6 www.cnmat.berkeley.edu (Center for New long and distinguished career as teacher Music and Audio Technologies, CNMAT). -

Alessandro Striggio Mass for 40 and 60 Voices

GCDSA 921623 Alessandro Striggio New release information February 2012 Mass for 40 and 60 voices NOTES (ENG) NOTES (FRA) As his starting point for a brand new recording of C’est à la polychoralité de la Renaissance et au the music from the polychoral Renaissance and « Baroque monumental » que Hervé Niquet dédie the “monumental Baroque”, with Alessandro son nouvel enregistrement, en recréant les Striggio’s 40 and 60-part Missa sopra Ecco sì beato célébrations musicales dans la cathédrale de Santa giorno leading the way, Hervé Niquet turns to the Maria del Fiore à l’occasion d’un jour de fête en musical celebrations for a feast day occasion in l’honneur de Saint-Jean Baptiste : la messe à 40 et the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence 60 voix de Alessandro Striggio, Missa sopra Ecco sì in honour of St John the Baptist, adding a trio of beato giorno, est accompagnée du motet Ecce works by Orazio Benevoli, another specialist in beatem lucem, lui aussi à 40 voix et du même multi-parted choral works, and Striggio’s motet compositeur, et d’un trio d’œuvres de Orazio Benevoli, Ecce beatem lucem, also scored for 40 voices. autre « spécialiste » de la musique chorale « monumentale ». For sessions in Notre-Dame du Liban in Paris, using an edition of the Mass by Dominique Visse, Pour l’enregistrement de l’œuvre à Notre-Dame du originating in 1978, Niquet gathered 60 singers Liban à Paris, basé sur une édition de la Messe Alessandro Striggio (c.1536-1592) (as called for in the Agnus Dei) plus instrumentalists réalisée par Dominique Visse -

Remarks on the Festivities of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Prague (1585)

Musicologica Brunensia 51 / 2016 / 1 DOI: 10.5817/MB2016-1-2 Remarks on the Festivities of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Prague (1585) Jan Baťa / [email protected] Ústav hudební vědy, Filozofická fakulta, Univerzita Karlova, Praha, CZ Abstract The festivities of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Prague and Landshut in June 1585 have already attracted much attention among historians. This article considers the musical part of the celebration that has yet not been discussed in detail. Using extant narrative, iconographi- cal and musical sources, it focuses on the first part of the festivity which took place at Prague Castle. It postulates a hypothesis that the forty-part motet Ecce beatam lucem from the Man- tuan composer and instrumentalist Alessandro Striggio (1536/37–1592) based on the text of German musician and poet Paulus Melissus-Schede (1539–1602) was performed in St. Vitus’ cathedral. Key words Paulus Melissus (1539–1602), Philippe de Monte (1521–1603), motet, multiple-choir music, Or- der of the Golden Fleece, Prague, Renaissance festivities, Alessandro Striggio (1536/37–1592), Ratsschulbibliothek Zwickau 25 Jan Baťa Remarks on the Festivities of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Prague (1585) The Order of the Golden Fleece is one of the most renowned chivalric orders. It was founded in 1430 by Phillip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1397–1467) to cultivate the ideal of Christian chivalry and to maintain the Christian faith. After the extinction of the Burgundian dynasty, the sovereignty of the Order passed to the Habsburg kings of Spain, where it remained until 1700 when the last of the Spanish Habsburgs, Charles II, died. -

Story of Spem in Alium, At

SPEM IN ALIUM Spem in alium numquam habui praeter in te Deus Israel qui irascéris et propitius eris et omnia peccata hominum in tribulatione dimittis. Domine Deus, Creator coeli et terrae, respice humilitatem nostram. Spem in alium is a forty part motet composed by Englishman, Thomas Tallis [c.1505‐ 1585], organist and composer to successive sovereigns throughout the course of the upheavals wrought in England by the Protestant Revolt. This motet ranks with the greatest musical compositions. The text is taken from a paraphrase of words in the Book of Judith where the children of Israel faced slaughter at the hands of the Assyrian general, Holofernes. Hope in any other than Thee I have never had, O God of Israel, whose anger may yet may be appeased as Thou forgivest all the sins man commits in his distress. Lord God, Creator of Heaven and Earth, look upon us in our lowliness. The words appear in a Responsum in the ancient Sarum rite of Mass, predecessor of the Tridentine rite. No passage in the Book of Judith reflects the content of this prayer precisely, but it manifests the recourse to humility and complete trust in God of the heroine before she sets out to relieve the Israelites by bewitching Holofernes with her beauty, watching as he lapses into a drunken stupor, then cuts off his head. There is debate as to when, and for what occasion, Tallis wrote this remarkable work. On the wikipedia website it is said to have been written during Elizabeth’s reign [1558‐1603]. The author of the material there quotes a letter written some 40 years on by one Thomas Wateridge who asserts that an unidentified Duke had incited English composers to improve on a motet heard “in Queene Elizabeth’s time” and written by an Italian, that Tallis wrote the work in consequence and that the Duke rewarded him by placing his own gold chain around Tallis’s neck. -

4.-Monteverdi-And-Orfeo.Pdf

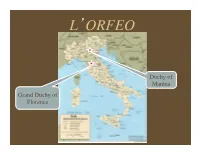

L’ORFEO Duchy of Mantua Grand Duchy of Florence L’ORFEO Gonzaga Family, Dukes of Mantua Mantuan Ducal Palace (1639) L’ORFEO Opera spreads from its Florentine origins to the court of Mantua, which has strong political and artistic ties to Florence. L’ORFEO Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) L’ORFEO Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) Considered the composer of the first “great” opera, L’Orfeo (1607) Defines the Baroque notion of the “Two Practices” Ideas of affect based in the theories of Plato and Aristotle Extreme affects in music are expressed in use of dissonance, especially unprepared dissonances L’ORFEO Baroque Theater, Cesky Krumlov, Czech Republic L’ORFEO Monteverdi’s music is characterized by the Seconda Prattica dictum, Prima le parole, poi la musica. (“First the words, then the music”) Music follows the text, especially when the music breaks “the rules” L’ORFEO Libretto: Alessandro STRIGGIO (based on L’Euridice of Rinuccini) Written for Accademia degli Invaghiti L’ORFEO Prologue with 5 Acts Striggio puts story into a Classical 5-Act structure L’ORFEO Prologue Act I Act II Act III Act IV Act V L’ORFEO Prologue (Apparition of Music) Act I: Arcadia (Wedding) Act II: Arcadia (Death of Euridice) Act III: Hades (Crossing Over) Act IV: Hades (The Bargain, and the Loss of Euridice) Act V: Arcadia (Deus ex Machina and Apotheosis of Orfeo) L’ORFEO Monteverdi imposes MUSICAL structure on libretto with modal organization and use of forms L’ORFEO Toccata and Prologue (Overture and Apparition of Music) Act I: Arcadia (Wedding) Act II: Arcadia (Death -

Davitt Moroney, Harpsichord Sarabande Tempo Di Gavotta Gique

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, December 1, 2013, 3pm Bach Partita No. 6, in E minor, bwv 830 (1731) Hertz Hall Toccata Allemanda Corrente Air Davitt Moroney, harpsichord Sarabande Tempo di Gavotta Gique PROGRAM Harpsichord by John Phillips (Berkeley, 2010), Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Partita No. 1, in B-flat major,bwv 825 (1726) based on an instrument by Johann Heinrich Gräbner (Dresden, 1722) Præludium Allemande Corrente Sarabande Menuets 1 & 2 Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Giga Bach Partita No. 5, in G major, bwv 829 (1730) Præambulum Allemande Corrente Sarabande Tempo di Minuetta Passepied Gique INTERMISSION 2 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 3 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES BACH’S PARTITAS When Bach published them as a set in 1731, 1739, comprising the most important volume called each of his suites Partie. But Bach knew he was 46 and at the height of his powers. He of organ music ever published. A fourth vol- that these great suites were not entirely French. y the time he wrote the harpsichord had already written about 800 works—includ- ume came out late in 1741, with the “Goldberg” Telemann, who loved French music, once dis- B works now known as the six Partitas, ing more than 200 organ pieces, over 200 can- Variations. He had thus covered several different armingly criticized his own concertos—and Bach was already an experienced composer of tatas, two or three Passions, sets of sonatas, par- stylistic bases: (1) Suites (Partitas); (2) Overture concerto is by definition an Italian form—by keyboard suites. -

And Elbląg of the Renaissance Era

The Beginnings of Musical Italianità in Gdańsk and Elbląg of the Renaissance Era AGNIESZKA LESZCZYŃSKA University of Warsaw Institute of Musicology The Beginnings of Musical Italianità in Gdańsk and Elbląg of the Renaissance Era Musicology Today • Vol. 10 • 2013 DOI: 10.2478/muso-2014-0001 In the second half of the sixteenth century almost the with the Italian language and culture. A sizeable group of whole of Europe was gradually engulfed by the fashion for settlers from the Apennine Peninsula had lived in Cracow Italian music. The madrigal became the favourite genre, from the beginning of the century, and that community which entered the repertory in different countries both in expanded significantly in 1518, after the arrival in Poland its original version and as contrafactum, intabulation or of Bona Sforza, the newly wedded wife of King Sigismund as the basis for missa parodia1. The madrigal and related I.4 Those brought to Poland by Bona included musicians: genres, such as canzona alla villanesca, also became the Alessandro Pesenti from Verona, who had previously subject of imitations, often composed by musicians who served as organist at the court of Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, had no links to Italy at all. Other genres employed by and who was active at Bona’s Cracovian court during the Italian composers, above all masses and motets, were also years 1521-1550, and Lodovico Pocenin, a cantor from of great interest to musicians throughout the continent. Modena, whose name appears in the records in 15275. It Undoubtedly it was the activity of the numerous is not impossible that Pesenti, as an organist, was in some Italian, mainly Venetian, printing houses which played way and to some degree responsible for the fact that the a decisive role in promoting these works; in terms of two Polish sources of keyboard music created ca 1548 titles produced, they held the leading position in Europe2. -

Spem in Alium Nunquam Habui

Basses Spem in alium nunquam habui A motet for 40 voices by Thomas Tallis (c.1505 – 1585) Edited by Philip Legge Notes Except for the unplanned visit to London in June 1567 by to Italy from 1566 to April 1567, which plausibly might the Mantuan gentleman, diplomat and composer Ales- have resulted in an encounter with Striggio, and an in- sandro Striggio senior, who came bringing performance vitation for him to visit London. FitzAlan possessed the parts of his 40-voice Missa sopra Ecco sì beato giorno, largest musical establishment outside the court, and in it would seem otherwise unlikely Thomas Tallis would 1556 had purchased from Mary Tudor the fabled Non- have received inspiration for his own sublime motet in such Palace, England’s largest Renaissance building, as 40 parts, Spem in alium nunquam habui. The rediscovery his country residence. The music collection held in the of the mass by Davitt Moroney and his researches have library there is known to have been extensive, as in 1596 confirmed most of the salient details of this story, in par- a catalogue was drawn up, which happens to reveal the ticular verifying the account of one Thomas Wateridge, a existence of a score of Spem in alium. Nonsuch also pos- law student at the Temple: sessed an octagonal banqueting hall with four first-floor balconies, which intriguingly suggests the architectural In Queen Elizabeth’s time yere was a songe sen[t] into England features that Tallis incorporated into his composition: it is of 30 parts (whence ye Italians obteyned ye name to be called conceivable he designed the work to be sung not only in Apices of ye world) wch beeinge songe mad[e] a heavenly the round, but perhaps with four of the eight choirs sing- Harmony.