Spem in Alium the Virtual Choir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janet Cardiff

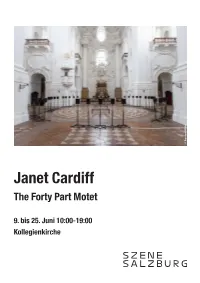

© Bernhard Müller Janet Cardiff The Forty Part Motet 9. bis 25. Juni 10:00-19:00 Kollegienkirche Janet Cardiff The Forty Part Motet Eine Bearbeitung von Spem in Alium Nunquam Habui, 1573 von Thomas Tallis Die kanadische Künstlerin Janet Cardiff hat Die in British Columbia lebende Janet Forty Part Motet wurde ursprünglich produziert mit ihrem international gefeierten Projekt Cardiff entwickelt, meist zusammen mit von Field Art Projects . The Forty Part Motet eine der emotionals- George Bures Miller, seit Jahren Installatio- In Kooperation mit: Arts Council of England, Cana- ten und poetischsten Klanginstallation der nen, Audio- und Video-Walks, die regelmä- da House, Salisbury Festival and Salisbury Cathedral letzten Jahre geschaffen. Die Sommersze- ßig mit Preisen ausgezeichnet werden. Ihre Choir, Baltic Gateshead, The New Art Galerie Walsall, ne 2021 bringt dieses berührende Hörerleb- Einzelausstellungen, die zwischen Wien Now Festival Nottingham nis erstmals nach Salzburg und installiert es und Washington zu sehen waren, sind Er- Gesungen von: Salisbury Cathedral Choir im sakralen Raum der Kollegienkirche. lebnisse für alle Sinne. The Forty Part Mo- Aufnahme & Postproduction: SoundMoves Die Grundlage der Arbeit bildet ein 40-stim- tet hat bereits Besucher*innen von der Tate Editiert von: Georges Bures Miller miges Chorstück, das aus vierzig Lautspre- Gallery bis zum MOMA begeistert. Eine Produktion von: Field Art Projects chern, die kreisförmig angeordnet sind, ab- gespielt wird. Janet Cardiff hat die Stimmen „While listening to a concert you are nor- Mit Unterstützung von der Motette Spem in Alium des englischen mally seated in front of the choir, in tradi- Renaissance-Komponisten Thomas Tallis tional audience position. (…) Enabling the aus dem 16. -

Motive and Spatialization in Thomas Tallis' Spem in Alium Kevin Davis

Motive and Spatialization in Thomas Tallis’ Spem in Alium Kevin Davis Abstract This paper is an analysis of Thomas Tallis’ 40-voice motet Spem in Alium. A piece of this scale and complexity posed challenges in terms of voice leading and counterpoint in this musical style due to its forces, scale, and complexity. In this analysis I suggest that Spem in Alium, due to the peculiarities of its nature, compelled Tallis to experiment with two specific elements—motive and spatialization, the specific treatment of which arises from the fundamental properties counterpoint and voice-leading and combines to create this unique form of antiphonal music. From this combination of factors, the piece’s distinctive “polyphonic detailism” emerges. 1 Origins of work and project Suggestions as to how and why such a work came to be are varied and unreliable. In her book Thomas Tallis and His Music in Victorian England, Suzanne Cole lists a variety of possible reasons claimed by different writers: an attempt to improve upon a 36-voice work of Ockeghem, for quasi-political reasons, as a response to a royal payment of 40 pounds, as a protest on behalf of forty generations of English Catholics slandered by the Protestant Reformation, and for Elizabeth I’s 40th birthday celebration2. Paul Doe in his book Tallis also suggests that is might have been for the sake of personal fulfillment, though as a sole motivation seems less likely.3 Thomas Legge in his preface to the score makes the most convincing argument as to its origin however: inspired by a performance of mass of 40 voices by Alessandro Striggio in London, June of 1557, Tallis was encouraged to undertake the challenge of composing a work with similar forces. -

Tallis's Spem in Alium

Spem in Alium – a comparatively review of fourteen recordings by Ralph Moore Background We know less about Thomas Tallis than Shakespeare or any other major cultural figure of the Tudor age; definite facts are few and reasonable inferences and conjectures are many, starting even with the dates of his birth – presumed to be around 1505 - and death - either 20th or 23rd November, 1585. The exact site of his grave in the chancel of the parish of St Alfege Church, Greenwich, is lost. We have no authenticated portrait. What we do know is that despite being a recusant Catholic, he not only survived those perilous times but prospered under a succession of Protestant monarchs, the sole Catholic being Edward VII’s sister Mary, who reigned for only five years, from 1553-1558. He was so valued and respected that Elizabeth gave him the lease on a manor house and a handsome income, and in 1575 he and his pupil William Byrd were granted an exclusive royal patent to print and publish polyphonic music. The key to his survival must lie in his discretion, flexibility and, above all, prodigious talent: he is indubitably one of the greatest English composers of his or any age and a towering figure in Renaissance choral music. His masterpiece is certainly the forty-voice motet Spem in alium but here again, verified facts regarding its origin and first performance are few. The original manuscript is lost and our knowledge of the work is derived from another score prepared for the investiture in 1610 of James I’s elder son, Henry, as Prince of Wales, and used again for the coronation in 1625 of his younger brother, Charles I, next in line to the throne after Harry’s death in 1612 from typhoid fever at eighteen years old. -

The Tallis Scholars

Friday, April 10, 2015, 8pm First Congregational Church The Tallis Scholars Peter Phillips, director Soprano Alto Tenor Amy Haworth Caroline Trevor Christopher Watson Emma Walshe Clare Wilkinson Simon Wall Emily Atkinson Bass Ruth Provost Tim Scott Whiteley Rob Macdonald PROGRAM Josquin Des Prez (ca. 1450/1455–1521) Gaude virgo Josquin Missa Pange lingua Kyrie Gloria Credo Santus Benedictus Agnus Dei INTERMISSION William Byrd (ca. 1543–1623) Cunctis diebus Nico Muhly (b. 1981) Recordare, domine (2013) Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) Tribute to Caesar (1997) Byrd Diliges dominum Byrd Tribue, domine Cal Performances’ 2014–2015 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 26 CAL PERFORMANCES PROGRAM NOTES he end of all our exploring will be Josquin, who built on the cantus firmus tradi- Tto arrive where we started and know the tion of the 15th century, developing the freer place for the first time.” So writes T. S. Eliot in parody and paraphrase mass techniques. A cel- his Four Quartets, and so it is with tonight’s ebrated example of the latter, the Missa Pange concert. A program of cycles and circles, of Lingua treats its plainsong hymn with great revisions and reinventions, this evening’s flexibility, often quoting more directly from performance finds history repeating in works it at the start of a movement—as we see here from the Renaissance and the present day. in opening soprano line of the Gloria—before Setting the music of William Byrd against moving into much more loosely developmen- Nico Muhly, the expressive beauty of Josquin tal counterpoint. Also of note is the equality of against the ascetic restraint of Arvo Pärt, the imitative (often canonic) vocal lines, and exposes the common musical fabric of two the textural variety Josquin creates with so few ages, exploring the long shadow cast by the voices, only rarely bringing all four together. -

Voice of Fire: Sensory Museum Experiences and Digital Reproduction

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-07-15 Voice of Fire: Sensory Museum Experiences and Digital Reproduction McDougall, Lauren McDougall, L. (2013). Voice of Fire: Sensory Museum Experiences and Digital Reproduction (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28662 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/821 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Voice of Fire: Sensory Museum Experiences and Digital Reproduction by Lauren McDougall A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA JULY, 2013 © Lauren McDougall 2013 ii Abstract The purchase of the painting Voice of Fire by the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) ignited one of Canada’s most heated artistic debates. Focusing on Voice of Fire and the NGC website, this study analyzed how digital reproduction of art on a museum website contributes to a sensory understanding of museum experience. Communicative technologies in the form of websites, social media and high-resolution images have changed spectatorship but continue to be problematic when essential features of the painting are dependent on physical and sensory museum ‘experience’. -

Spem in Alium: the Virtual Choir Project

Spem in Alium: The Virtual Choir Project James Haupt April 28, 2003 - Table of Contents - Section 1 Introduction 1.1 A Brief History and Introduction .................................................................2 1.2 Computers and Digital Music .......................................................................2 1.3 Revival of the Part Book .................................................................................3 Section 2 Spem in Alium 2.1 Digitizing Spem in Alium ................................................................................5 Section 3 The Virtual Choir 3.1 Digitally Creating the Choir ..........................................................................5 3.2 Recording the Choir ........................................................................................6 3.3 Splicing the Notes ...........................................................................................7 Section 4 Looking Ahead 4.1 Future Logistics ...............................................................................................9 4.2 The Performance .............................................................................................9 4.3 Future Applications ......................................................................................10 Section 5 Credits 5.1 Credits .............................................................................................................11 Works Cited...............................................................................................................12 -

The Tallis Scholars Perform Program of Sacred Renaissance Vocal Music in Symphony Center Presents Special Concert at Fourth Presbyterian Church

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: March 21, 2016 Eileen Chambers/CSO, 312-294-3092 Lisa Dell/The Silverman Group, Inc., 312-932-9950 Photos Available By Request [email protected] THE TALLIS SCHOLARS PERFORM PROGRAM OF SACRED RENAISSANCE VOCAL MUSIC IN SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS SPECIAL CONCERT AT FOURTH PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Tuesday, April 5, at 7:30 p.m. CHICAGO—Acclaimed British vocal ensemble The Tallis Scholars, led by the group’s director Peter Phillips, performs a program of sacred Renaissance music in a Symphony Center Presents Special Concert on Tuesday, April 5 at 7:30 p.m. at Fourth Presbyterian Church (126 E. Chestnut Street). The ensemble’s program includes a cappella selections from composers William Byrd, John Taverner, Richard Davy, Thomas Tallis, and Alfonso Ferrabosco. The program includes two motets—Laetentur coeli and Vigilate—by English composer William Byrd, a pupil of Thomas Tallis. Also on the program is John Taverner’s Missa Western Wynde, a setting of sacred text to the tune of a popular Renaissance love song and the free composed choral work Salve Regina by Richard Davy, as well as another setting of the same Marian hymn by William Byrd. The ensemble also performs Thomas Tallis’ Lamentations I, a multilayered musical work that laments not only the biblical fall of Jerusalem, but reflects the sorrow of a Catholic composer living in Queen Elizabeth’s Protestant England. Completing the program is Lamentations, a setting of the same biblical text as the Tallis work by Italian composer Alfonso Ferrabosco. This Renaissance-focused concert program features music composed during Shakespeare’s lifetime and is part of the citywide SHAKESPEARE 400 CHICAGO celebration. -

Story of Spem in Alium, At

SPEM IN ALIUM Spem in alium numquam habui praeter in te Deus Israel qui irascéris et propitius eris et omnia peccata hominum in tribulatione dimittis. Domine Deus, Creator coeli et terrae, respice humilitatem nostram. Spem in alium is a forty part motet composed by Englishman, Thomas Tallis [c.1505‐ 1585], organist and composer to successive sovereigns throughout the course of the upheavals wrought in England by the Protestant Revolt. This motet ranks with the greatest musical compositions. The text is taken from a paraphrase of words in the Book of Judith where the children of Israel faced slaughter at the hands of the Assyrian general, Holofernes. Hope in any other than Thee I have never had, O God of Israel, whose anger may yet may be appeased as Thou forgivest all the sins man commits in his distress. Lord God, Creator of Heaven and Earth, look upon us in our lowliness. The words appear in a Responsum in the ancient Sarum rite of Mass, predecessor of the Tridentine rite. No passage in the Book of Judith reflects the content of this prayer precisely, but it manifests the recourse to humility and complete trust in God of the heroine before she sets out to relieve the Israelites by bewitching Holofernes with her beauty, watching as he lapses into a drunken stupor, then cuts off his head. There is debate as to when, and for what occasion, Tallis wrote this remarkable work. On the wikipedia website it is said to have been written during Elizabeth’s reign [1558‐1603]. The author of the material there quotes a letter written some 40 years on by one Thomas Wateridge who asserts that an unidentified Duke had incited English composers to improve on a motet heard “in Queene Elizabeth’s time” and written by an Italian, that Tallis wrote the work in consequence and that the Duke rewarded him by placing his own gold chain around Tallis’s neck. -

Winter Choir Concert Lawrence University Choirs Phillip A

Winter Choir Concert Lawrence University Choirs Phillip A. Swan and Stephen M. Sieck, conductors Special guests: Appleton East High School Easterners Dan Van Sickle ’03, conductor Friday, February 23, 2018 8:00 p.m. Lawrence Memorial Chapel Viking Chorale Nature as Metaphor O Ignis Spiritus Paracliti Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) Abendlich schon rauscht der Wald from Gartenlieder, op. 3 Fanny Hensel (1805-1847) The Dark Around Us from Great Trees Gwyneth Walker (b. 1947) Viking Chorale and Concert Choir Lumen Abbie Betinis (b. 1980) Concert Choir Collaborations Spem in Alium Thomas Tallis (1505-1585) Épithète moussue Christian Messier '19 (b. 1996) Chamber Ensembles Abendfeier in Venedig Clara Wieck Schumann from Drei gemischte Chöre (1819-1896) Trial Scene Liza Lehmann from Nonsense Songs from ‘Alice in Wonderland’ (1862-1918) The Poet’s Dream Asha Srinivasan (b. 1980) Appleton East High School Easterners Lullaby Daniel Elder (b. 1986) Easterners and Concert Choir Let My Love Be Heard Jake Runestad (b. 1986) Cantala Awe and Wonder (Hope, Strength, and Joy) Méditationes Sacrae Andrej Makor I. Visionem (b. 1987) Méditations de la Vierge Marie Marie-Claire Saindon II. Le secret de Dieu (b. 1984) Abigail Keefe, violin 1, Rachael Teller, violin 2, Nathaniel Sattler, viola, David Sieracki, cello Laudate Dominum Levente Gyöngyösi (b. 1975) Klangfarben Andrew Rindfleisch II. Die Vogelrufe (b. 1963) Moon Goddess Jocelyn Hagen (b. 1980) Gabrielle Claus and Frances Lewelling, piano Kelci Page, percussion Because I am human Dale Trumbore (b. 1987) Emily Richter and Sarah Scofield, soloists Unwritten Natasha Bedingfield Danielle Brisebrois Wayne Rodrigues arr. Kerry Marsh (b. 1976) Soloists: Susie Francy, Caroline Granner, Meghan Burroughs, Bea McManus, Samantha Stone, Maren Dahl, Grace Foster, Erin McCammond-Watts, Anna Mosoriak, Rehanna Rexroat, Marieke de Koker, Allie Horton Gabrielle Claus, piano Ta Na Solbici (And So We Dance in Resia) Samo Vovk (b. -

Thomas Tallis the Complete Works

Thomas Tallis The Complete Works Tallis is dead and music dies. So wrote William Byrd, Tallis's most distinguished pupil, capturing the esteem and veneration in which Tallis was held by his fellow composers and musical colleagues in the 16th century and, indeed, by the four monarchs he served at the Chapel Royal. Tallis was undoubtedly the greatest of the 16th century composers; in craftsmanship, versatility and intensity of expression, the sheer uncluttered beauty and drama of his music reach out and speak directly to the listener. It is surprising that hitherto so little of Tallis's music has been regularly performed and that so much is not satisfactorily published. This series of ten compact discs will cover Tallis's complete surviving output from his five decades of composition, and will include the contrafacta, the secular songs and the instrumental music - much of which is as yet unrecorded. Great attention is paid to performance detail including pitch, pronunciation and the music's liturgical context. As a result new editions of the music are required for the recordings, many of which will in time be published by the Cantiones Press. 1 CD 1 Music for Henry VIII This recording, the first in the series devoted to the complete works of Thomas Tallis, includes church music written during the first decade of his career, probably between about 1530 and 1540. Relatively little is known about Tallis’s life, particularly about his early years. He was probably born in Kent during the first decade of the sixteenth century. When we first hear of him, in 1532, he is organist of Dover Priory, a small Benedictine monastery consisting of about a dozen monks. -

King's Singers

CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer SIGNUMCLASSICS YELLOW Catalogue No. SIGCD071 BLACK Job Title SPEM Page Nos. ALSO from the King’s singers CD SINGLE Gesualdo Tenebrae Six SIGCD056 Christmas SIGCD502 Responsories SIGCD048 1605 Treason and Dischord Sacred Bridges SIGCD065 SIGCD061 DVD 201 248 www.signumrecords.com www.kingssingers.com Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com. For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer SIGNUMCLASSICS YELLOW Catalogue No. SIGCD071 BLACK Job Title SPEM Page Nos. thomas tallis Spem in alium 1 Thomas Tallis Spem in Alium [8.22] 2 Interview with the King’s Singers [6.14] Total Time [14.36] Frank Schulze C The King’s Singers would like to thank Erika Esslinger and Alistair Dixon for their assistance with this project. P 2006 The copyright in this recording is owned by Signum Records Ltd. C 2006 The copyright in this CD booklet, notes and design is owned by Signum Records Ltd. Engineer - Mike Hatch Any unauthorised broadcasting, public performance, copying or re-recording of Signum Compact Producer - Adrian Peacock Discs constitutes an infringement of copyright and will render the infringer liable to an action by The King’s Singers Editor - Stephen Frost law. Licences for public performances or broadcasting may be obtained from Phonographic Recorded in Angel Studios, London Performance Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this booklet may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval Recording dates - 19th & 20th October 2004 system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording David Hurley, Robin Tyson, Paul Phoenix, Philip Lawson, Artwork and design - Woven Design or otherwise, without prior permission from Signum Records Ltd. -

The Cardinall's Musick Illuminate His Complex Masterpieces” – Berta Joncus, BBC Music Magazine

The Cardinall’s Musick Selected Reviews Gunpowder, Treason & Plot - Wigmore Hall, November 2019 “the final monumental motet: Byrd’s 'Ad Dominum cum tribularer' – when I was in distress I called on the Lord. This heartfelt plea for truth in the face of lies and deceitfulness was emotionally devastating. The musical and dramatic contrasts, as eight parts wove miraculously distinct and as one, were breathtaking. We can only hope that the Cardinall’s Musick continue to examine and reanimate this repertoire for another thirty years.” - Amanda-Jane Doran, Classical Source In the Company of Heaven – Wigmore Hall, 2018/19 season three-part series “the differentiation of the individual lines, each sung with strong character, enabled Carwood to subtly highlight individual lines and phrases, which simultaneously injected muscularity into the evolving polyphony, with the brightness of the soprano and alto adding further ‘uplift’.” – [Part I] Claire Seymour, Opera Today “It’s the tone that strikes you first with this ensemble. A trend towards ever whiter, narrower, purer sound from early music groups has given us some wonderfully gauzy, translucent, but sometimes rather wan performances, so it’s startling to hear such muscularity and full-voiced release. Just eight singers (sometimes shrinking down to a consort of four, five or six) set the dome above the Wigmore Hall stage ringing, refusing to let this lovely music settle into mere prettiness.” – [Part I] Alexandra Coghlan, The Tablet “The eight singers who formed The Cardinall’s Musick on this occasion - some of whom are familiar figures from other ensembles such as The Tallis Scholars and The Sixteen - know this repertory and how to perform it like the proverbial back of the hand.