Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Lyric Opera Brings 'The Lighthouse'

Boston Lyric Opera brings ‘The Lighthouse’ to JFK By Harlow Robinson | GLOBE CORRESPONDENT JONATHAN WIGGS/GLOBE STAFF Thomas Hase, lighting designer for ‘‘The Lighthouse,’’ at the JFK Library. In New England we love our lighthouses. Beacons of safety in the stormy dark, they adorn the jagged coastline like timeless monuments to our maritime history. But lighthouses, especially in the pre- automation era, also gave rise to more unsettling feelings and questions. Who lives there, anyhow? What weird phenomena might lighthouse keepers witness, or imagine, during those long days and nights of lonely vigil, fog, and spray? These questions also fascinated distinguished British composer Peter Maxwell Davies. For many years, Davies, 77, has lived on Sanday, one of the remote Orkney Islands north of Scotland, where lighthouses are crucial fixtures of the ruggedly romantic landscape. In 1979, Davies transformed his interest in local maritime lore into music when he completed “The Lighthouse,’’ a chamber opera in a prologue and one act. Since its 1980 premiere at the Edinburgh Festival, “The Lighthouse’’ has become one of the most popular of all 20th-century operas, having been performed by more than 100 different companies. This week, Boston Lyric Opera will present four performances in Smith Hall at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. British stage director Tim Albery will make his BLO debut, as will set and costume designer Camellia Koo. BLO’s British-born music director David Angus will conduct. “The Lighthouse’’ is the latest offering in BLO’s Opera Annex program, created to stage productions in alternative, non-theatrical venues around the city. -

The Persistence of Parody in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Insight - University of Cumbria The Persistence of Parody in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies Richard E McGregor It’s all about time. Indeed there is not a single piece of musical composition that is not in some way about time. And for Davies the manipulation of time is rooted in his understanding of late Medieval and early Renaissance musical techniques and practices refracted through post 12-note pitch manipulation. In this article I take to task the uncritical use of terminology in relation to the music of Peter Maxwell Davies. Though my generating text is the quotation from John Warnaby’s 1990 doctoral thesis: Since parody is implied in the notion of using pre-existing material as a creative model, it can be argued that, as traditionally understood, it is rarely absent from Maxwell Davies’s music[1] this is in no wise a criticism of Warnaby for whom I have much respect, and especially his ability to be able to perceive patterns, trends and unifying features between works and across extended periods of time. Rather, it is a commentary on particular aspects of Davies’s music which are often linked together under the catch-all term ‘parody’: EXAMPLE 1: Dali’s The Persistence of Memory[2] I take as my starting point the painting The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali, a painting which operates on a number of levels, the most obvious, because of the immediate imagery, being that is has something to do with time. -

Expanded Perceptions of Identity in Benjamin Britten's Nocturne, Op. 60

EXPANDED PERCEPTIONS OF IDENTITY IN BENJAMIN BRITTEN’S NOCTURNE, OP. 60 Anna Grace Perkins, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Paul B. Berry, Major Professor Bernardo Illari, Minor Professor Benjamin Brand, Committee Member John P. Murphy, Chair of the Department of Music Theory, History, and Ethnomusicology Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Perkins, Anna Grace. Expanded Perceptions of Identity in Benjamin Britten’s Nocturne, Op. 60. Master of Music (Musicology), May 2008, 67 pp., 6 musical examples, references, 53 titles. A concentrated reading of Benjamin Britten’s Nocturne through details of the composer’s biography can lead to new perspectives on the composer’s identity. The method employed broadens current understandings of Britten’s personality and its relationship to the music. After creating a context for this kind of work within Britten scholarship, each chapter explores a specific aspect of Britten’s identity through the individual songs of the Nocturne. Chapter 2 focuses on how Britten used genres in a pastoral style to create his own British identity. Chapter 3 concentrates on the complex relationship between Britten's homosexuality and his pacifism. Chapter 4 aims to achieve a deeper understanding of Britten's idealization of innocence. The various aspects of Britten’s personality are related to one another in the Conclusion. Copyright 2008 by Anna Grace Perkins ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF EXAMPLES…………………………………………………………………..……iv Chapter 1. -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

Frank Rosolino

FRANK ROSOLINO s far as really being here, weeks has been a complete ball. have. Those I've met and heard in- this was my first visit to Also, on a few nights John Taylor clude John Marshall, Wally Smith, Britain. I was here in 1953 was committed elsewhere; so Bobby Lamb, Don Lusher, George Awith Stan Kenton, which Gordon Beck come in to take his Chisholm. I liked George's playing was just an overnight thing; so place. He's another really excellent very much; he has a nice conception twenty years have elapsed in be- player. You've got some great play- and feel, good soul, and he plays tween. I've been having an abso- ers round here! with an extremely good melodic lutely beautiful time here, and en- They're equal to musicians I sense. joying London. work with in the States. I mean, it As for my beginnings—I was Playing at Ronnie Scott's with doesn't matter where you are; once born and raised in Detroit, Michigan, me I had John Taylor on piano, Ron you've captured the feeling for jazz, until I was old enough to be drafted Mathewson on bass and Martin and you've been playing it practi- into the Service, which was the latter Drew on drums. Absolutely great cally all your life, you're a pro at it. part of '44. I started playing guitar players, every one of 'em. I can't tell I've heard so much about when I was nine or ten. My father you how much I enjoyed myself, and trombonist Chris Pyne that when I played parties and weddings on it just came out that way. -

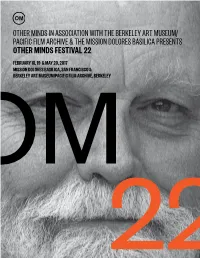

Other Minds in Association with the Berkeley Art

OTHER MINDS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/ PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE & THE MISSION DOLORES BASILICA PRESENTS OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL 22 FEBRUARY 18, 19 & MAY 20, 2017 MISSION DOLORES BASILICA, SAN FRANCISCO & BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE, BERKELEY 2 O WELCOME FESTIVAL TO OTHER MINDS 22 OF NEW MUSIC The 22nd Other Minds Festival is present- 4 Message from the Artistic Director ed by Other Minds in association with the 8 Lou Harrison Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive & the Mission Dolores Basilica 9 In the Composer’s Words 10 Isang Yun 11 Isang Yun on Composition 12 Concert 1 15 Featured Artists 23 Film Presentation 24 Concert 2 29 Featured Artists 35 Timeline of the Life of Lou Harrison 38 Other Minds Staff Bios 41 About the Festival 42 Festival Supporters: A Gathering of Other Minds 46 About Other Minds This booklet © 2017 Other Minds, All rights reserved 3 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR WELCOME TO A SPECIAL EDITION OF THE OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL— A TRIBUTE TO ONE OF THE MOST GIFTED AND INSPIRING FIGURES IN THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN CLASSICAL MUSIC, LOU HARRISON. This is Harrison’s centennial year—he was born May 14, 1917—and in addition to our own concerts of his music, we have launched a website detailing all the other Harrison fêtes scheduled in his hon- or. We’re pleased to say that there will be many opportunities to hear his music live this year, and you can find them all at otherminds.org/lou100/. Visit there also to find our curated compendium of Internet links to his work online, photographs, videos, films and recordings. -

HENRY and LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL of MUSIC SPRING 2017 Fanfare

HENRY AND LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC SPRING 2017 fanfare 124488.indd 1 4/19/17 5:39 PM first chair A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN One sign of a school’s stature is the recognition received by its students and faculty. By that measure, in recent months the eminence of the Bienen School of Music has been repeatedly reaffirmed. For the first time in the history of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, this spring one of the contestants will be a Northwestern student. EunAe Lee, a doctoral student of James Giles, is one of only 30 pianists chosen from among 290 applicants worldwide for the prestigious competition. The 15th Van Cliburn takes place in May in Ft. Worth, Texas. Also in May, two cello students of Hans Jørgen Jensen will compete in the inaugural Queen Elisabeth Cello Competition in Brussels. Senior Brannon Cho and master’s student Sihao He are among the 70 elite cellists chosen to participate. Xuesha Hu, a master’s piano student of Alan Chow, won first prize in the eighth Bösendorfer and Yamaha USASU Inter national Piano Competition. In addition to receiving a $15,000 cash prize, Hu will perform with the Phoenix Symphony and will be presented in recital in New York City’s Merkin Concert Hall. Jason Rosenholtz-Witt, a doctoral candidate in musicology, was awarded a 2017 Northwestern Presidential Fellowship. Administered by the Graduate School, it is the University’s most prestigious fellowship for graduate students. Daniel Dehaan, a music composition doctoral student, has been named a 2016–17 Field Fellow by the University of Chicago. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 33 Online, Summer 2017

Features: Understanding Britten’s Lachrymae through Billy Budd Volume 33 Summer 2017 Online Issue 2017 Online Summer 33 Volume Exploring the Transcription of the First Movement of Journal of the American ViolaSociety American the of Journal Brahms’s Sonata op. 120, no. 1 Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Summer 2017: Volume 33, Online Issue p. 3 From the Editor p. 4 From the President News & Notes p. 5 In Review: 43rd International Viola Congress: Daphne Capparelli Gerling shares her impressions of the viola congress held in Cremona, Italy. Feature Articles p. 10 From Clarinet to Viola: “Awkward and Unappealing”: Exploring the Transcription of the First Movement of Brahms’s Sonata op. 120, no. 1: Mandy Isaacson provides a detailed look at Brahms’s transcription methods by investigating the differences between the clarinet and viola versions of the first movement of the F minor sonata. p. 29 Understanding Benjamin Britten’s Lachrymae through Billy Budd: Josquin Larsen uses Britten’s opera Billy Budd to add multiple layers of context—both historical and compositional—to Britten’s viola masterwork, Lachrymae. Departments p. 43 With Viola in Hand: The Pièces de Concours: Melissa Claisse interviews Jutta Puchhammer-Sédillot about her recent recording and edition of these “rediscovered treasures from turn-of-the-century France.” p. 48 Outreach: Les Jacobson details the extensive and career-long outreach efforts of violist Richard Young. p. 56 Orchestral Matters: Julie Edwards introduces us to the viola section of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra. p. 63 Book Review: David Rose reviews The Accompaniment in “Unaccompanied” Bach: Interpreting the Sonatas and Partitas for Violin, by Stanley Ritchie. -

MAXWELL DAVIES Symphony No

Peter MAXWELL DAVIES Symphony No. 6 Time and the Raven • An Orkney Wedding with Sunrise Royal Philharmonic Orchestra • Maxwell Davies Peter Maxwell Davies (b. 1934) becomes a symbol of warning – in my work, dark music At the outset, we hear guests arriving, out of extremely Symphony No. 6 • Time and the Raven • An Orkney Wedding with Sunrise hints at what could be, were attitudes to nationalism not to bad weather, at the hall. This is followed by the modifyʼ. Hence the non-triumphant ending, hinting at the processional, where the guests are solemnly received by Symphony No. 6 (1996) Time and the Raven (1995) manner in which the anthems ʻcan get along together, and the bride and bridegroom, and presented with their first accommodate each other. This is, perhaps, the most glass of whisky. The band tunes up, and we get on with Symphony No. 6 was composed during the first half of The art of the occasional overture, commissioned for a “real” for which we can hopeʼ. Despite the note of caution, the dancing proper. This becomes ever wilder, as all 1996. It has three movements. The starting-off point is a specific celebration, has given rise to some remarkably the orchestration is of suitably celebratory proportions, concerned feel the results of the whisky, until the lead slow tune from Time and the Raven, a work fluent and even inspired exercises in the genre in the with triple woodwind, a sizeable (though by no means fiddle can hardly hold the band together any more. We commissioned to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the nineteenth century. -

Purcell King Arthur Semi-Staged Performance Tuesday 3 October 2017 7Pm, Hall

Purcell King Arthur semi-staged performance Tuesday 3 October 2017 7pm, Hall Academy of Ancient Music AAM Choir Richard Egarr director/harpsichord Daisy Evans stage director Jake Wiltshire lighting director Thomas Lamers dramaturg Ray Fearon narrator Louise Alder soprano Mhairi Lawson soprano Reginald Mobley countertenor Charles Daniels tenor Ivan Ludlow baritone Ashley Riches bass-baritone Marco Borggreve Marco Rosie Purdie assistant stage director Jocelyn Bundy stage manager Hannah Walmsley assistant stage manager There will be one interval of 20 minutes after Part 1 Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 Part of Academy of Ancient Music 2017–18 Generously supported by the Geoffrey C Hughes Charitable Trust as part of the AAM Purcell Opera Cycle Confectionery and merchandise including organic ice cream, quality chocolate, nuts and nibbles are available from the sales points in our foyers. Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight marks the second instalment in a directly to a modern audience in the Brexit three-year series of semi-stagings of Purcell era. The subject of national identity – works, co-produced by the Barbican and central to King Arthur – has never seemed Academy of Ancient Music. Following a more pertinent. hugely successful Fairy Queen last season, AAM Music Director Richard Egarr and This piece contains some of Purcell’s stage director Daisy Evans once again most visit and beautiful music – including combine in this realisation of Purcell’s the celebrated aria ‘Fairest isle’ – and King Arthur. -

Profesionalizacija in Specializacija Glasbenega Dela ▪︎ The

doi: https://doi.org/10.26493/978-961-7055-86-3.87-104 In the Shadow of Parry, Stanford and Mackenzie: Musical Composition studies in the principal London Conservatories from 1918 to 1945 Niall O’Loughlin Univerza v Loughboroughu Loughborough University In the early 20th century, the main British music institutions, which at- tracted the attention of prospective composers, were the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music, both located in London. What is particularly notable is that the early principals of the Royal Academy were almost always prominent composers and the directors of the Royal College were very often composers, too. The history of the founding and the back- ground of these two conservatories gives some understanding of their po- sition and standing by the end of World War I. In the early 1820s patriotic amateurs promoted ideas for the founda- tion of a Royal Academy of Music, but this was initially opposed by the mu- sic profession, which felt that there were too many musicians anyway. The professionals then tried unsuccessfully to associate the proposed academy with the long-standing Philharmonic Society, which later commissioned Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony during the same period. In the end the am- ateurs, principally John Fane, eleventh Earl of Westmorland (also known as Lord Berghersh) with assistance of royalty, notably King George IV, suc- ceeded in establishing the Academy of Music in 1822 in London, the first of the British conservatories, receiving its royal charter in 1830 to become the Royal Academy of Music. To create a strong credibility for the institution the founders needed to appoint a distinguished principal, although the choice was perhaps not that difficult. -

Over 100 Opera Makers

#OPERAHARMONY CREATING OPERAS IN ISOLATION 1 3 WELCOME TO #OPERA HARMONY FROM FOUNDER – ELLA MARCHMENT Welcome to #OperaHarmony. #Opera Harmony is a collection of opera makers from across the world who, during this time of crisis, formed an online community to create new operas. I started this initiative when the show that I was rehearsing at Dutch National Opera was cancelled because of the lockdown. Using social media and online platforms I invited colleagues worldwide to join me in the immense technical and logistical challenge of creating new works online. I set the themes of ‘distance’ and ‘community’, organised artist teams, and since March have been overseeing the creation of twenty new operas. All the artists involved in #OperaHarmony are highly skilled professionals who typically apply their talents in creating live theatre performances. Through this project, they have had to adapt to working in a new medium, as well as embracing new technologies and novel ways of creating, producing, and sharing work. #OperaHarmony’s goal was to bring people together in ways that were unimaginable prior to Covid-19. Over 100 artists from all the opera disciplines have collaborated to write, stage, record, and produce the new operas. The pieces encapsulate an incredibly dark period for the arts, and they are a symbol of the unstoppable determination, and community that exists to perform and continue to create operatic works. This has been my saving grace throughout lockdown, and it has given all involved a sense of purpose. When we started building these works we had no idea how they would eventually be realised, and it is with great thanks that we acknowledge the support of Opera Vision in helping to both distribute and disseminate these pieces, and also for establishing a means in which audiences can be invited into the heart of the process too .