Evocatio Deorum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umbria from the Iron Age to the Augustan Era

UMBRIA FROM THE IRON AGE TO THE AUGUSTAN ERA PhD Guy Jolyon Bradley University College London BieC ILONOIK.] ProQuest Number: 10055445 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10055445 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis compares Umbria before and after the Roman conquest in order to assess the impact of the imposition of Roman control over this area of central Italy. There are four sections specifically on Umbria and two more general chapters of introduction and conclusion. The introductory chapter examines the most important issues for the history of the Italian regions in this period and the extent to which they are relevant to Umbria, given the type of evidence that survives. The chapter focuses on the concept of state formation, and the information about it provided by evidence for urbanisation, coinage, and the creation of treaties. The second chapter looks at the archaeological and other available evidence for the history of Umbria before the Roman conquest, and maps the beginnings of the formation of the state through the growth in social complexity, urbanisation and the emergence of cult places. -

00010853-Preview.Pdf

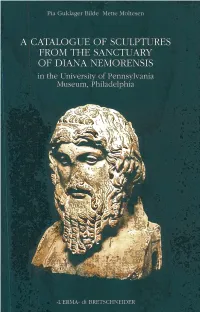

ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI Supplemen turn XXIX A CATALOGUE OF SCULPTURES FROM THE SANCTUARY OF DIANA NEMORENSIS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM, PHILADELPHIA A Catalogue of Sculptures from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER ROMAE MMII ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI, SUPPL. XXIX Accademia di Danimarca - Via Omero, 18 - 00197 Rome - Italy Lay-out by the editors © 2002 <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, Rome PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF GRANTS FROM Knud Højgaards Fond Novo Nordisk Fonden University of Pennsylvania. Museum of archaeology and anthropology A catalogue of sculptures from the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia / by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER , 2002. - 95 p. : ill. ; 30 cm. (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementum ; 29) ISBN 88-8265-211-4 CDD 21. 731.4 1. Sculture in marmo - Collezioni 2. Filadelfia - University of Pennsylvania - Museum of archaeology and anthropology - Cataloghi I. Guldager Bilde, Pia II. Moltesen, Mette The journal ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI (ARID) publishes studies within the main range of the Academy's research activities: the arts and humanities, history and archaeology. Intending contributors should get in touch with the editors, who will supply a set of guide- lines and establish a deadline. A print of the article, accompanied y a disk containing the text should be sent to the editors, Accademia di Danimarca, 18 Via Omero, I - 00197 Roma, tel. +39 06 32 65 931, fax +39 06 32 22 717. -

Magic in Private and Public Lives of the Ancient Romans

COLLECTANEA PHILOLOGICA XXIII, 2020: 53–72 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1733-0319.23.04 Idaliana KACZOR Uniwersytet Łódzki MAGIC IN PRIVATE AND PUBLIC LIVES OF THE ANCIENT ROMANS The Romans practiced magic in their private and public life. Besides magical practices against the property and lives of people, the Romans also used generally known and used protective and healing magic. Sometimes magical practices were used in official religious ceremonies for the safety of the civil and sacral community of the Romans. Keywords: ancient magic practice, homeopathic magic, black magic, ancient Roman religion, Roman religious festivals MAGIE IM PRIVATEN UND ÖFFENTLICHEN LEBEN DER ALTEN RÖMER Die Römer praktizierten Magie in ihrem privaten und öffentlichen Leben. Neben magische Praktik- en gegen das Eigentum und das Leben von Menschen, verwendeten die Römer auch allgemein bekannte und verwendete Schutz- und Heilmagie. Manchmal wurden magische Praktiken in offiziellen religiösen Zeremonien zur Sicherheit der bürgerlichen und sakralen Gemeinschaft der Römer angewendet. Schlüsselwörter: alte magische Praxis, homöopathische Magie, schwarze Magie, alte römi- sche Religion, Römische religiöse Feste Magic, despite our sustained efforts at defining this term, remains a slippery and obscure concept. It is uncertain how magic has been understood and practised in differ- ent cultural contexts and what the difference is (if any) between magical and religious praxis. Similarly, no satisfactory and all-encompassing definition of ‘magic’ exists. It appears that no singular concept of ‘magic’ has ever existed: instead, this polyvalent notion emerged at the crossroads of local custom, religious praxis, superstition, and politics of the day. Individual scholars of magic, positioning themselves as ostensi- bly objective observers (an etic perspective), mostly defined magic in opposition to religion and overemphasised intercultural parallels over differences1. -

Cneve Tarchunies Rumach

Classica, Sao Paulo, 718: 101-1 10, 199411995 Cneve Tarchunies Rumach R.ROSS HOLLOWAY Center for Old World Archaeology and Art Brown University RESUMO: O objetivo do Autor neste artigo e realizar um leitura historica das pinturas da Tumba Francois em Vulci, detendo-se naquilo que elas podem elucidar a respeito da sequencia dos reis romanos do seculo VI a.C. PALAVRAS CHAVE: Tumba Francois; realeza romana; uintura mural. The earliest record in Roman history, if by history we mean the union of names with events, is preserved in the paintings of an Etruscan tomb: the Francois Tomb at Vulci. The discovery of the Francois Tomb took place in 1857. The paintings were subsequently removed from the walls and became part of the Torlonia Collection in Villa Albani where they remain to this day. The decoration of the tomb, like much Etruscan funeral art, draws on Greek heroic mythology. It also included a portrait of the owner, Vel Saties, and beside him the figure of a woman named Tanaquil, presumably his wife (this figure has become almost completely illegible). In view of the group of historical personages among the tomb paintings, this name has decided resonance with better known Tanaquil, in Roman tradition the wife of Tarquinius Priscus. The historical scene of the tomb consists of five pairs of figures drawn from Etruscan and Roman history. These begin with the scene (A) Mastarna (Macstma) freeing Caeles Vibenna (Caile Vipinas) from his bonds (fig.l). There follow four scenes in three of which an armed figure dispatches an unarmed man with his sword. -

Ovid at Falerii

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2014 The Poet in an Artificial Landscape: Ovid at Falerii Joseph Farrell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Farrell, Joseph. (2014). “The Poet in an Artificial Landscape: Ovid at alerii.F ” In D. P. Nelis and Manuel Royo (Eds.), Lire la Ville: fragments d’une archéologie littéraire de Rome antique (pp. 215–236). Bordeaux: Éditions Ausonius. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Poet in an Artificial Landscape: Ovid at Falerii Abstract For Ovid, erotic elegy is a quintessentially urban genre. In the Amores, excursions outside the city are infrequent. Distance from the city generally equals distance from the beloved, and so from the life of the lover. This is peculiarly true of Amores, 3.13, a poem that seems to signal the end of Ovid’s career as a literary lover and to predict his future as a poet of rituals and antiquities. For a student of poetry, it is tempting to read the landscape of such a poem as purely symbolic; and I will begin by sketching such a reading. But, as we will see, testing this reading against what can be known about the actual landscape in which the poem is set forces a revision of the results. And this revision is twofold. In the first instance, taking into account certain specific eaturf es of the landscape makes possible the correction of the particular, somewhat limited interpretive hypothesis that a purely literary reading would most probably recommend, and this is valuable in itself. -

Veiling Among Men in Roman Corinth: 1 Corinthians 11:4 and the Potential Problem of East Meeting West

JBL 137, no. 2 (2018): 501-517 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15699/jbl. 1372.2018.346666 Veiling among Men in Roman Corinth: 1 Corinthians 11:4 and the Potential Problem of East Meeting West PRESTON T. MASSEY [email protected] Indiana Wesleyan University, Marion, IN 46953 Close attention to the original meaning of the words κατακαλύπτω (1 Cor 11:6) and κατά κεφαλής εχων ( 1 Cor 11:4) permits a translation only of a material head covering. These words do not describe the process of letting hair hang down loosely. These words are consistently used in Classical and Hellenistic Greek to describe the action of covering the head with a textile covering of some kind. In spite of sustained efforts by advocates, the long-hair theory still has not sue- ceeded in gaining an entry into standard reference works. The original edition of BAGD in 1957, the revised edition in 1979, and the more recent edition of BDAG in 2000 all support the view that the text of 1 Cor 11:2-16 describes an artificial textile head covering of some kind. In 1988, Richard Oster published a provocative article detailing the cultural practice of Roman men wearing head coverings in a liturgical setting.*1 His study called attention to the value of the artifactual evidence as well as the many literary texts documenting the widespread use of veiling among Roman men. His purpose was to establish the fact that it was obligatory for elite Roman men in certain ritual settings to wear a head covering. His article did not focus on the element of shame. -

La Latinità Di Ariccia E La Grecità Di Nemi. Istituzioni Civili E Religiose a Confronto

ANNA PASQUALINI La latinità di Ariccia e la grecità di Nemi. Istituzioni civili e religiose a confronto Il titolo del mio intervento è solo apparentemente contraddittorio. Esso è volto a mettere in relazione due contesti sociali tanto vicini nello spazio quanto distanti per impianto culturale e per funzioni politiche: la città di Ariccia e il lucus Dianius. Del bosco sacro a Diana e della selva che lo circonda si è scritto moltissimo soprattutto da quando esso costituì il fulcro di un’opera straordinaria per ricchezza ed originalità quale quella di Sir James Frazer1 Su Ariccia, invece, come comunità cittadina e sulle sue istituzioni politiche e religiose non si è riflettuto abbastanza2 e, in particolare, queste ultime non sono state messe sufficientemente in relazione con il santuario nemorense. Cercherò, quindi, di svolgere qualche considerazione nella speranza di fornire un piccolo contributo alla definizione degli intricati problemi del territorio aricino. Ariccia, come comunità politica, appare nelle fonti letterarie all’epoca del secondo Tarquinio, il tiranno per eccellenza, spregiatore del Senato e del popolo3. Al Superbo viene attribuita una forte vocazione al controllo politico del Lazio attraverso un’accorta rete di alleanze con i maggiorenti del Lazio, primo fra tutti il più eminente di essi, e cioè Ottavio Mamilio di Tuscolo, che è anche suo genero (Livio I 49); è ancora Tarquinio che, secondo le fonti (Livio I 50), indirizza la politica dei Latini convocando i federati in assemblea presso il lucus sacro a Ferentina4. La scelta del luogo non è casuale. Il bosco sacro è stato localizzato nel territorio di Ariccia, ma esso viene considerato idealmente collegato con il Monte Albano, cioè con il centro sacrale dei Latini, 1 La prima edizione dell’opera, The Golden Bough, risale al 1890. -

An Examination of Cavità 254 in Orvieto, Italy, and Its Primary Usage As an Etruscan Quarry

An Examination of Cavità 254 in Orvieto, Italy, and its Primary Usage as an Etruscan Quarry Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Graduate Program in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies by Kelsey Latsha May 2018 Copyright by Kelsey Latsha © 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Project is the culmination of years of work on the excavation of Cavità 254 under the direction of Professor David George and Claudio Bizzarri. I would like to thank Professor George for the opportunity to work on the site of Cavità 254 and for introducing me to the world of the Etruscans during my time at Saint Anselm College. I am forever grateful for Professor George’s mentorship that motivated me to pursue a graduate degree in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies at Brandeis University. I would also like to thank Doctor Paolo Binaco a fantastic teacher, friend, and archaeologist. Paolo has guided me in the right direction, while simultaneously sparking excitement in asking new questions about our unique site. Thank you, Paolo, for the unforgettable adventures to see Orvieto’s “pyramids” and for teaching me everything Etruscan. This thesis would not be possible without the immense support of the Department of Classical Studies at Brandeis. I especially would like to thank my Advisor Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow for her enthusiastic support of my project from its early beginnings and always pushing me to better my writing and research. -

Archaeological and Literary Etruscans: Constructions of Etruscan Identity in the First Century Bce

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND LITERARY ETRUSCANS: CONSTRUCTIONS OF ETRUSCAN IDENTITY IN THE FIRST CENTURY BCE John B. Beeby A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: James B. Rives Jennifer Gates-Foster Luca Grillo Carrie Murray James O’Hara © 2019 John B. Beeby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT John B. Beeby: Archaeological and Literary Etruscans: Constructions of Etruscan Identity in the First Century BCE (Under the direction of James B. Rives) This dissertation examines the construction and negotiation of Etruscan ethnic identity in the first century BCE using both archaeological and literary evidence. Earlier scholars maintained that the first century BCE witnessed the final decline of Etruscan civilization, the demise of their language, the end of Etruscan history, and the disappearance of true Etruscan identity. They saw these changes as the result of Romanization, a one-sided and therefore simple process. This dissertation shows that the changes occurring in Etruria during the first century BCE were instead complex and non-linear. Detailed analyses of both literary and archaeological evidence for Etruscans in the first century BCE show that there was a lively, ongoing discourse between and among Etruscans and non-Etruscans about the place of Etruscans in ancient society. My method musters evidence from Late Etruscan family tombs of Perugia, Vergil’s Aeneid, and Books 1-5 of Livy’s history. Chapter 1 introduces the topic of ethnicity in general and as it relates specifically to the study of material remains and literary criticism. -

Castelli Romani” (Roman Castles) Are a Group of Towns in the Province of Rome

EUROPE ITALY GENZANO DI ROMA LAZIO The “Castelli Romani” (Roman Castles) are a group of towns in the province of Rome. The area of the “Castelli” occupies a volcanic and fertile area characterized by ancient settlements and flourishing agriculture. The old crater is now occupied by two lakes, Lake Nemi and Lake Albano. The recent name Roman Castles derives from the villages built around some villas and palaces where rich noble families spent the summer. The “Castelli Romani” are: •Albano Laziale •Ariccia •Castel Gandolfo •Colonna •Frascati •Genzano di Roma •Grottaferrata •Lanuvio •Lariano •Marino •Monte Compatri •Monte Porzio Catone •Nemi •Rocca di Papa •Rocca Priora •Velletri EVENTS “CASTELLI ROMANI” PARK HISTORICAL GEOLOGICAL INFORMATION INFORMATION UPPER SECONDARY SCHOOL: LICEO SCIENTIFICO “GIOVANNI VAILATI” ““CASTELLICASTELLI ROMANIROMANI”” REGIONALREGIONAL PARKPARK Genzano and its surroundings are included in the area of the “Castelli Romani” Regional Park . The chestnut is the most important tree in our area. The holm-oak tree is very important, too. Genzano’s events Here’s a short guide that makes you discover Genzano’s traditions. The “Infiorata” The most important attraction is the “Infiorata”, a folkloristic and religious exhibition known all over the world. The “Infiorata” has taken place on Sunday following Corpus Domini since 1778. It consists of a huge flower carpet divided into many images that covers the street that joins the cathedral with the main square. Many famous artists have contributed to the “Infiorata”. A masked parade walk on the flower carpet. The people wear traditional clothes that date back to the 17th century. At least 350,000 flower petals, in addition to earth, beans and sometimes wood cuttings, are necessary to make the carpet. -

Volume 14 Winter 2012 the Etruscans in Leiden and Amsterdam: “Eminent Women, Powerful Men” Double Exhibition on Ancient Italian Culture Perspective

Volume 14 Winter 2012 The Etruscans In Leiden and Amsterdam: “Eminent Women, Powerful Men” Double Exhibition on Ancient Italian culture perspective. The exhibition in Leiden tombs still adorn the romantic land- focuses on Etruscan women, the exhibi- scapes of Umbria and Tuscany. tion in Amsterdam on Etruscan men. Etruscan art, from magnificent gold On display will be more than 600 jewels to colorful tomb paintings, con- pieces from the museums’ own collec- tinues to fire the imagination of lovers tions and from many foreign museums. of Italy and art. “Etruscans: Eminent The ruins of imposing Etruscan Women, Powerful Men,” provides a October 14 - March 18, 2012 detailed introduction to Etruscan civi- The National Museum of lization in a visually delightful exhibi- Antiquities in Leiden and the Allard tion. Pierson Museum in Amsterdam pres- The Etruscans flourished hundreds ents the fascinating world of the of years before the Romans came to Etruscans to the public in a unique dou- power in Italy. Their civilization ble exhibition. The two museums tell reached its height between 750 and 500 the tale of Etruscan wealth, religion, BC, Etruscan society was highly devel- power and splendor, each from its own Left & Right: Brolio bronzes. Center: Replica of the Latona at Leiden. oped; women continued on page 15 Scientists declare the XXVIII Convegno di tions with Corsica and featured specific studies of Etruscan material found in the Fibula Praenestina and its engraved with the earliest archaic Latin Studi Etruschi ed Italici inscription. The matter of its authentic- Corsica and Populonia excavations at Aleria. Rich in minerals inscription to be genuine ity has been a question for a long time. -

Temples with Transverse Cellae in Republican and Early Imperial Italy

BABesch 82 (2007, 333-346. doi: 10.2143/BAB.82.2.2020781) Forms of Cult? Temples with transverse cellae in Republican and early Imperial Italy Benjamin D. Rous Abstract This article presents an analysis of a particular temple type that first appeared during the Late Republic, the temple with transverse cella. In the past this particular cella-form has been interpreted as a solution to spatial constraints. In more recent times it has been argued that the cult associated with the temple was the decisive factor in the adoption of the transverse cella. Neither theory, when considered in isolation, can fully and con- vincingly explain the particular forms of both Republican and Imperial temples. Rather, it can be argued that a combination of pragmatic and above all aesthetic considerations has played a major role in the particular archi- tecture of these temples.* INTRODUCTION archaeological evidence, even though the remains of the building itself have never been excavated. In the fourth book of his famous treatise on archi- Furthermore, this is one of the temples actually tecture, Vitruvius mentions a specific temple-type, mentioned by Vitruvius in his treatise. In yet an- whose basic characteristic is that all the features other case, the temple of Aesculapius in the Latin normally found on the short side of the temple colony of Fregellae, although construction activi- have been transferred to the long side. What this ties have destroyed virtually the entire temple basically means is that the pronaos still constitutes building, a reconstruction of a transverse cella the front part of the temple, but instead of being nevertheless seems likely on the basis of the scant longitudinally developed, the cella is rotated 90º remains we do have.