Planned Obsolescence and Consumer Protection: the Unregulated Extended Warranty and Service Contract Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does the Planned Obsolescence Influence Consumer Purchase Decison? the Effects of Cognitive Biases: Bandwagon

FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS ESCOLA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO VIVIANE MONTEIRO DOES THE PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE INFLUENCE CONSUMER PURCHASE DECISON? THE EFFECTS OF COGNITIVE BIASES: BANDWAGON EFFECT, OPTIMISM BIAS AND PRESENT BIAS ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR. SÃO PAULO 2018 VIVIANE MONTEIRO DOES THE PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE INFLUENCE CONSUMER PURCHASE DECISIONS? THE EFFECTS OF COGNITIVE BIASES: BANDWAGON EFFECT, OPTIMISM BIAS AND PRESENT BIAS ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR Applied Work presented to Escola de Administraçaõ do Estado de São Paulo, Fundação Getúlio Vargas as a requirement to obtaining the Master Degree in Management. Research Field: Finance and Controlling Advisor: Samy Dana SÃO PAULO 2018 Monteiro, Viviane. Does the planned obsolescence influence consumer purchase decisions? The effects of cognitive biases: bandwagons effect, optimism bias on consumer behavior / Viviane Monteiro. - 2018. 94 f. Orientador: Samy Dana Dissertação (MPGC) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. 1. Bens de consumo duráveis. 2. Ciclo de vida do produto. 3. Comportamento do consumidor. 4. Consumidores – Atitudes. 5. Processo decisório – Aspectos psicológicos. I. Dana, Samy. II. Dissertação (MPGC) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título. CDU 658.89 Ficha catalográfica elaborada por: Isabele Oliveira dos Santos Garcia CRB SP-010191/O Biblioteca Karl A. Boedecker da Fundação Getulio Vargas - SP VIVIANE MONTEIRO DOES THE PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE INFLUENCE CONSUMERS PURCHASE DECISIONS? THE EFFECTS OF COGNITIVE BIASES: BANDWAGON EFFECT, OPTIMISM BIAS AND PRESENT BIAS ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR. Applied Work presented to Escola de Administração do Estado de São Paulo, of the Getulio Vargas Foundation, as a requirement for obtaining a Master's Degree in Management. Research Field: Finance and Controlling Date of evaluation: 08/06/2018 Examination board: Prof. -

Discovering Our True Identity Consumerism Can Encourage the Least Attractive Human Traits— Avarice, Aggression, and Self-Centeredness

Discovering Our True Identity Consumerism can encourage the least attractive human traits— avarice, aggression, and self-centeredness. By giving us a new identity as members of God’s Body, the Eucharist can form us in fidelity, other-centeredness, and proper joy, which are counter- Christian Reflection cultural to the ethos of consumer culture. A Series in Faith and Ethics Prayer Scripture Reading: 1 Corinthians 11:17-34 Responsive Reading† Bread of the world, in mercy broken, Wine of the soul, in mercy shed, Focus Article: By whom the words of life were spoken, Discovering Our True And in whose death our sins are dead. Identity Look on the heart by sorrow broken, (Consumerism, pp. 32-38) Look on the tears by sinners shed; Suggested Articles: And be Thy feast to us the token, That by Thy grace our souls are fed. Which Kingdom? (Consumerism, pp. 83-89) Reflection Past the Blockade “Consumerism is more than the mere creation and consumption (Consumerism, pp. 48-50) of goods and services,” Medley writes. It encourages the mis- taken belief that our needs can only be satisfied by excessive consumption. Soon consumers “need to need and desire to de- sire. Instead of consuming goods themselves, they consume the meanings of goods as those have been constructed through ad- vertising and marketing. In a sense, they become what they buy.” Examples are easy to find: we buy “Harley-Davidson motorcycles to symbolize personal freedom, Nike shoes to sug- gest ‘I want to be like Mike,’ and clothing from Abercrombie and Fitch to communicate chic casualness.” We buy self-images that are greedily centered on competition and self-promotion. -

Lloyd's Minimum Standards

LLOYD’S MINIMUM STANDARDS MS1.1 – UNDERWRITING STRATEGY & PLANNING October 2017 1 MS1.1 – UNDERWRITING STRATEGY & PLANNING UNDERWRITING MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES, MINIMUM STANDARDS AND REQUIREMENTS These are statements of business conduct required by Lloyd’s. The Principles and Minimum Standards are established under relevant Lloyd’s Byelaws relating to business conduct. All managing agents are required to meet the Principles and Minimum Standards. The Requirements represent the minimum level of performance required of any organisation within the Lloyd’s market to meet the Minimum Standards. Within this document the standards and supporting requirements (the “must dos” to meet the standard) are set out in the blue box at the beginning of each section. The remainder of each section consists of guidance which explains the standards and requirements in more detail and gives examples of approaches that managing agents may adopt to meet them. UNDERWRITING MANAGEMENT GUIDANCE This guidance provides a more detailed explanation of the general level of performance expected. They are a starting point against which each managing agent can compare its current practices to assist in understanding relative levels of performance. This guidance is intended to provide reassurance to managing agents as to approaches which would certainly meet the Principles and Minimum Standards and comply with the Requirements. However, it is appreciated that there are other options which could deliver performance at or above the minimum level and it is fully acceptable for managing agents to adopt alternative procedures as long as they can demonstrate the Requirements to meet the Principles and Minimum Standards. DEFINITIONS AFR: actuarial function report Benchmark Premium: The price for each risk at which the managing agent is expected to deliver their required results, in line with the approved Syndicate Business Plan. -

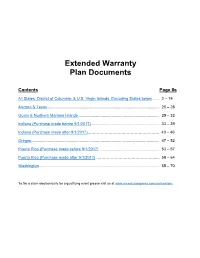

Extended Warranty Coverage

Extended Warranty Plan Documents Contents Page #s All States, District of Columbia, & U.S. Virgin Islands, Excluding States below ...... 2 – 19 Arizona & Texas ..................................................................................................... 20 – 28 Guam & Northern Mariana Islands ......................................................................... 29 – 32 Indiana (Purchase made before 9/1/2017) ............................................................. 33 – 39 Indiana (Purchase made after 9/1/2017)………………………………………………. 40 – 46 Oregon.................................................................................................................... 47 – 52 Puerto Rico (Purchase made before 9/1/2017) ...................................................... 53 – 57 Puerto Rico (Purchase made after 9/1/2017) ……………………………………….... 58 – 64 Washington ............................................................................................................. 65 – 70 To file a claim electronically for a qualifying event please visit us at www.americanexpress.com/onlineclaim. All States, District of Columbia, & U.S. Virgin Islands, Except States below Back to top EXTENDED WARRANTY DESCRIPTION OF COVERAGE Underwritten by AMEX Assurance Company Administrative Office, 20022 N. 31st Ave. MC: 08-01-20 Phoenix AZ 85027 For purchases charged to Your Account, Extended Warranty will extend the terms of the original manufacturer's warranty on warranties of five (5) years or less that are eligible in the United States of America, -

An Experimental Investigation of Extended Warranties

Volume 64 Issue 2 Article 4 7-1-2019 Protecting Consumers Through Mandatory Disclosures: An Experimental Investigation of Extended Warranties Breagin K. Riley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons Recommended Citation Breagin K. Riley, Protecting Consumers Through Mandatory Disclosures: An Experimental Investigation of Extended Warranties, 64 Vill. L. Rev. 285 (2019). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol64/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Riley: Protecting Consumers Through Mandatory Disclosures: An Experiment 2019] PROTECTING CONSUMERS THROUGH MANDATORY DISCLOSURES: AN EXPERIMENTAL INVESTIGATION OF EXTENDED WARRANTIES BREAGIN K. RILEY* AND AHMED E. TAHA** IMAGINE that you go to a consumer electronics store and buy a large- Iscreen television for $1,499. At the checkout counter, the cashier asks if you also wish to purchase an extended warranty for $249, which will pro- vide you three additional years of coverage beyond the manufacturer’s one-year warranty. Would you buy the extended warranty? What would drive your decision? If you are like most consumers, you would make this decision with little idea of the probability that the television will break down during the extended warranty’s coverage period and the cost of repairing it. But how would your decision and motivations change if the cashier told you there is only a 3% chance of the television needing repair during the first four years you own it and that the average cost of repairing the television is $300? These questions are the focus of this Article. -

Your Financial Road Map: Where Do You Want to Go?

YOUR FINANCIAL ROAD MAP: WHERE DO YOU WANT TO GO? DAY: 11 TITLE: YOUR MONEY: Consumer Awareness – Consumption TARGET COMPETENCY: Understand the influence of advertising and examine the impact of our own consumption on our financial health and the environment OBJECTIVES: Recognize the connections among advertising and consumption choices Become critical consumers of youth-directed advertising and marketing Determine whether corporations have a responsibility to disclose information to consumers Examine the impact of your own consumption on the world Consider the impact of consumption on your overall financial health HANDOUTS/MATERIALS Computer/internet for showing The Story of Stuff http://storyofstuff.org/index.php (Watch online or download for free; can also request a free DVD from website). Lesson 6 – from Buy, Use, Toss? A Closer Look at the Things We Buy http://www.facingthefuture.org/Curriculum/BuyCurriculum/BuyUseToss/tabid/469/ Default.aspx Hand out: Analyzing an Ad (from Why Buy? lesson) Hand out: Marketing to Teens – Advertising Strategies http://www.media- awareness.ca/english/resources/educational/handouts/advertising_marketing/mtt_adverti sing_strategies.cfm LESSON SUMMARY: Students begin by considering the purpose of advertising. Each student critically analyzes an advertisement that appeals to him or her, weighing advertised information against their needs as consumers. Students discuss whether additional information should be included in product advertisements and how advertising connects to consumption choices. LESSON OUTLINE: MINUTES CONTENT Alternative Lesson: Practical Money Skills, Lesson 11: Consumer Awareness https://www.practicalmoneyskills.com/foreducators/lesson_plans/teens.php Before Class: Ask students to bring an advertisement they find compelling. It Washoe County School District – Financial Education Curriculum Page 1 of 5 can be any medium: online, print, TV or radio, bumper sticker or t-shirt, etc. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Limits To

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Limits to Growth: Analyzing Technology’s Role THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Informatics by Meena Devii Muralikumar Thesis Committee: Professor Bonnie Nardi, Chair Professor Bill Tomlinson Professor Josh Tanenbaum 2019 © 2019 Meena Devii Muralikumar DEDICATION To Professor Bonnie Nardi for her wonderfully astute thinking and guidance that has taught me to research and write with passion about things I truly care about and my family and friends for being a constant source of support and encouragement ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS v LIST OF FIGURES vi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2: ECONOMIC GROWTH 3 2.1 The Rebound Effect 3 2.2 Economic Growth 5 2.3 Conventional Economic vs. Ecological Economics 6 CHAPTER 3: ALTERNATE ECONOMIES 9 3.1 Post-growth, Steady State and Degrowth 9 3.2 Post-growth thinking for the world 11 CHAPTER 4: TECHNOLOGY AND ECONOMY 14 4.1 Technology and change 14 4.2 Other considerations for technologists 18 CHAPTER 5: CASE STUDIES 20 5.1 The Case for Commons 21 5.2 The Case for Transparency 25 5.3 The Case for Making and Do-It-Yourself (DIY) culture 31 CHAPTER 6: DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION 34 REFERENCES 38 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude for my committee chair, Professor Bonnie Nardi. She has encouraged me to read, think, and write and probably knows and believes in me more than I do. Her work that ties together technology in the current world and the problem of environmental limits will always be a source of inspiration for me. -

Planned Obsolescence

Consume more than you need “This is the dream Make you pauper Or make you queen Planned I won’t die lonely obsolescence (n.) I’ll have it all prearranged A method of stimulating consumer demand A grave that’s deep and wide enough by designing products that wear out or become outdated after limited use. For me and all my mountains o’ things” Lyrics from “Mountains o’ Things” by Tracy Chapman http://www.dictionary.com/browse/planned-obsolescence average number Before [World War II], plastic played of minutes a plastic a very limited role in bag is used before “ being thrown away material life. After the war, 12 [surplus] oil became the driving force behind the American economy, and number of plastic made from 1,000,000,000,000 bags used globally plastics, which are each year petroleum, became ubiquitous, used in everything from dry cleaning bags and dispos- minimum number able pens to Styrofoam and shrink-wrap. An ar- of years before ray of disposable products from plastic sil- a plastic bag verware to paper cups, meanwhile, enshrined 1,000 decomposes cleanliness and convenience… ” http://www.earth-policy.org/plan_b_updates/2014/update123 Excerpt from Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History by Ted Steinberg WASTE DEEP Issue Cards WASTE DEEP Issue Cards RCP WASTE DEEP 09-17 RCP WASTE DEEP 09-17 WASTE DEEP Issue Cards WASTE DEEP Issue Cards RCP WASTE DEEP 09-17 RCP WASTE DEEP 09-17 I am convinced that if we are to get on the right “ side of the world revolution, we as a nation must Men and women are sacrificed to theidols of profit undergo a radical revolution of values. -

Financial Literacy: the Hidden Curriculum, and Ecological Injustice

Journal of Sustainability Education Vol. 4, January 2013 ISSN: 2151-7452 Financial Literacy: the Hidden Curriculum, and Ecological Injustice Carmen Seda University of Texas at El Paso Keywords: Ecological injustice; sustainability; personal financial literacy; consumer; neoclassical principles; hidden curriculum Abstract: A historic overview, and examination of the curriculum for personal financial literacy suggest that a focus on neoclassical principles results in narrowing consumer understanding of their true power and true impact within a market economy socially and ecologically. Sustainability is taught as an isolated global problem, rather than in conjunction with personal financial literacy, maintaining a misperception that an individual consumer does not have power or influence over global ecological issues. This circumstance perpetuates a situation of what this paper posits as ecological injustice. Carmen Seda is an El Paso educator pursuing a PhD in Teaching, Learning and Culture at the University of Texas at El Paso studying the social and institutional context of literacy/biliteracy pedagogical practices, particularly as it effects social studies classrooms. A Texas teacher since 1989, her interest in economics and ecological education emerged as part of her service to economics teachers as a Social Studies Instructional Specialist Financial Literacy: the Hidden Curriculum, and Ecological Injustice As a result of the financial recession that began in the United States in Dec. 2007 (Kaiser, 2008), movements to consolidate the local economies of communities became a pressing concern. In October 2008, El Paso educators, business leaders, and community leaders formed a consortium to examine the problem from many facets (IAD, 2008). As an El Paso educator, I participated in the examination of curricula for personal financial literacy. -

Breaking Manufacturers' Aftermarket Monopoly and Restoring

APRIL 2020 Fixing America: Breaking Manufacturers’ Aftermarket Monopoly and Restoring Consumers’ Right to Repair DANIEL A. HANLEY CLAIRE KELLOWAY SANDEEP VAHEESAN 1 1 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................. 2 I. Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 II. History of Restricting Repair .............................................................. 4 The History of Open Aftermarkets ............................................................. 4 Early Efforts to Close Afternarkets ............................................................. 6 III. Methods of Restricting Repair .......................................................... 9 Tying of Aftermarket Parts and Service ...................................................... 9 Exclusive Dealing of Aftermarket Parts and Service ................................ 10 Refusal to Sell Essential Tools, Parts, Diagnostics, Manuals, and Software 10 Predatory and Exclusionary Design ........................................................ 11 Leveraging Copyright Law to Lock Software and Hardware .................... 12 Restrictive End User License Agreements ................................................ 13 IV. The Effects and Consequences of Restricted Repair ...................... 15 Increased Costs to Consumers ................................................................ 15 Stifling the Repair Economy and Local Resiliency .................................. -

Rescission, Restitution, and the Principle of Fair Redress: a Response to Professors Brooks and Stremitzer

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 47 Number 2 Winter 2013 pp.1-78 Winter 2013 Rescission, Restitution, and the Principle of Fair Redress: A Response to Professors Brooks and Stremitzer Steven W. Feldman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven W. Feldman, Rescission, Restitution, and the Principle of Fair Redress: A Response to Professors Brooks and Stremitzer, 47 Val. U. L. Rev. 1 (2013). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol47/iss2/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Feldman: Rescission, Restitution, and the Principle of Fair Redress: A Re Article RESCISSION, RESTITUTION, AND THE PRINCIPLE OF FAIR REDRESS: A RESPONSE TO PROFESSORS BROOKS AND STREMITZER Steven W. Feldman* I. INTRODUCTION Analyzing a remedy that the reporter for the Restatement (Third) of Restitution and Unjust Enrichment describes as having “[e]normous practical importance and theoretical interest,”1 scholars in recent years have produced a flood of articles covering contract rescission and restitution.2 In their 2011 Article in the Yale Law Journal, Remedies on and off Contract, Professors Richard Brooks and Alexander Stremitzer weigh in on the discussion.3 Relying on microeconomic theory, which reflects the perspective of rational buyers and sellers, the authors’ thesis is that current legal doctrine is too restrictive in allowing buyers’ rescission and too liberal in granting them restitution.4 Although other commentators * Attorney-Advisor, U.S. -

Unconscionability As a Sword: the Case for an Affirmative Cause of Action

Unconscionability as a Sword: The Case for an Affirmative Cause of Action Brady Williams* Consumers are drowning in a sea of one-sided fine print. To combat contractual overreach, consumers need an arsenal of effective remedies. To that end, the doctrine of unconscionability provides a crucial defense against the inequities of rigid contract enforcement. However, the prevailing view that unconscionability operates merely as a “shield” and not a “sword” leaves countless victims of oppressive contracts unable to assert the doctrine as an affirmative claim. This crippling interpretation betrays unconscionability’s equitable roots and absolves merchants who have already obtained their ill-gotten gains. But this need not be so. Using California consumer credit law as a backdrop, this Note argues that the doctrine of unconscionability must be recrafted into an offensive sword that provides affirmative relief to victims of unconscionable contracts. While some consumers may already assert unconscionability under California’s Consumers Legal Remedies Act, courts have narrowly construed the Act to exempt many forms of consumer credit. As a result, thousands of debtors have remained powerless to challenge their credit terms as unconscionable unless first sued by a creditor. However, this Note explains how a recent landmark ruling by the California Supreme Court has confirmed a novel legal theory that broadly empowers consumers—including debtors—to assert unconscionability under the State’s Unfair Competition Law. Finally, this Note argues that unconscionability’s historical roots in courts of equity—as well as its treatment by the DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z382B8VC3W Copyright © 2019 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc.