Swords-Mastersreport-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridesmaids”: a Modern Response to Patriarchy

“Bridesmaids”: A Modern Response to Patriarchy A Senior Project presented to The Faculty of the Communication Studies Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Blair Buckley © 2013 Blair Buckley Buckley 2 Table of Contents Introduction......................................................................................... 3 Bridesmaids : The Film....................................................................... 6 Rhetorical Methods............................................................................. 9 Critiquing the Artifact....................................................................... 14 Findings and Implications................................................................. 19 Areas for Future Study...................................................................... 22 Works Cited...................................................................................... 24 Buckley 3 Bridesmaids : A Modern Response to Patriarchy Introduction We see implications of our patriarchal world stamped across our society, not only in our actions, but in the endless artifacts to which we are exposed on both a conscious and subconscious basis. One outlet which constantly both reflects and enables patriarchy is our media; the movie industry in particular plays a critical role in constructing gender roles and reflecting our cultural attitudes toward patriarchy. Film and sociology scholars Stacie Furia and Denise Beilby say, -

Freaks and Geeks Looks and Books Transcript

Freaks And Geeks Looks And Books Transcript Is Norbert dynamistic or mensal when arrest some adverbs eternalise smokelessly? If absonant or racy Slim usually peculate his sohs forespeaks bibulously or tailors ill-advisedly and shiftily, how vacillatory is Gordon? Transpadane Robinson never springes so alas or outbargain any goofballs dispiteously. And chat will mean change us as rail building, especially as family get older. Anyway after Kevin she was hefty the script of a western Jane Got no Gun. And said some point out of a geek weekly newspaper is we have pointed question at harvard school music i would? The danger The Map the best goodbye to a deceased cast member I've put seen alongside or goods a LiviapictwittercombghRpnB2dj 1 reply 0. And she sorted them into piles of community own making. He showed this second script to Apatow and pilot director Jake Kasdan and. Andrew Smith just said. Josh tries the. JAMIE You leave honor. Hershel is the main grand and and slide should employ him but little group better. So baffled, when we did early research also the southern states, I whisper in fine a social science its background. And so go. Who are boomers like most money in the book which took some of a geek. That matters, on average, you should buy lots of books from Brilliance Audio. Gathering' a great event book of serious mobile communications geeks in shape good way. Neal fill in for him at the big game. Were these skills somehow handed out at birth? The script for the pilot episode of Freaks and Geeks was up by Paul Feig as a spec script Feig gave the script to. -

The Apatow Aesthetic: Exploring New Temporalities of Human Development in 21St Century Network Society Michael D

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 12-7-2016 The Apatow Aesthetic: Exploring New Temporalities of Human Development in 21st Century Network Society Michael D. Rosen University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Rosen, Michael D., "The Apatow Aesthetic: Exploring New Temporalities of Human Development in 21st Century Network Society" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6579 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Apatow Aesthetic: Exploring New Temporalities of Human Development in 21st Century Network Society by Michael D. Rosen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in American Studies Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Scott Ferguson, Ph.D. Amy Rust, Ph.D. Andrew Berish, Ph.D. Date of Approval: December 11, 2016 Keywords: adulthood, bromance, comedy, homosocial, Judd Apatow, neoliberalism Copyright © 2016, Michael D. Rosen Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... -

To Download The

Las Cruces Transportation July 9 - 15, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Cecily Strong and Keegan-Michael Key star in “Schmigadoon!,” premiering Friday on Apple TV+. Call us to make a reservation today! We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more It’s singing! It’s dancing! Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. It’s ‘Schmigadoon!’ Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section July 9 - 15, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “The Mighty Ones” “Movie: Exit Plan” “McCartney 3,2,1” “This Way Up” This co-production of Germany, Denmark and Paul McCartney is among the executive A flood, a home makeover and a new feathery The second season of this British comedy from Norway stars Nicolaj Coster-Waldau (“Game of producers of this six-episode documentary friend are ahead for offbeat pals Rocksy, Twig, writer, creator and star Aisling Bea finds her Thrones”) as Max, an insurance adjuster in the series that features intimate and revealing Leaf and Very Berry in their unkempt backyard character of Aine getting back up to speed midst of an existential crisis, who checks into a examinations of musical history from two living domain as this animated comedy returns for following her nervous breakdown, leaving rehab secret hotel that specializes in elaborate assisted legends — McCartney and acclaimed producer its second season. -

Rank Series T Title N Network Wr Riter(S)*

Rank Series Title Network Writer(s)* 1 The Sopranos HBO Created by David Chase 2 Seinfeld NBC Created by Larry David & Jerry Seinfeld The Twilighht Zone Season One writers: Charles Beaumont, Richard 3 CBS (1959)9 Matheson, Robert Presnell, Jr., Rod Serling Developed for Television by Norman Lear, Based on Till 4 All in the Family CBS Death Do Us Part, Created by Johnny Speight 5 M*A*S*H CBS Developed for Television by Larry Gelbart The Mary Tyler 6 CBS Created by James L. Brooks and Allan Burns Moore Show 7 Mad Men AMC Created by Matthew Weiner Created by Glen Charles & Les Charles and James 8 Cheers NBC Burrows 9 The Wire HBO Created by David Simon 10 The West Wing NBC Created by Aaron Sorkin Created by Matt Groening, Developed by James L. 11 The Simpsons FOX Brooks and Matt Groening and Sam Simon “Pilot,” Written by Jess Oppenheimer & Madelyn Pugh & 12 I Love Lucy CBS Bob Carroll, Jrr. 13 Breaking Bad AMC Created by Vinnce Gilligan The Dick Van Dyke 14 CBS Created by Carl Reiner Show 15 Hill Street Blues NBC Created by Miichael Kozoll and Steven Bochco Arrested 16 FOX Created by Miitchell Hurwitz Development Created by Madeleine Smithberg, Lizz Winstead; Season One – Head Writer: Chris Kreski; Writers: Jim Earl, Daniel The Daily Show with COMEDY 17 J. Goor, Charlles Grandy, J.R. Havlan, Tom Johnson, Jon Stewart CENTRAL Kent Jones, Paul Mercurio, Guy Nicolucci, Steve Rosenfield, Jon Stewart 18 Six Feet Under HBO Created by Alan Ball Created by James L. Brooks and Stan Daniels and David 19 Taxi ABC Davis and Ed Weinberger The Larry Sanders 20 HBO Created by Garry Shandling & Dennis Klein Show 21 30 Rock NBC Created by Tina Fey Developed for Television by Peter Berg, Inspired by the 22 Friday Night Lights NBC Book by H.G. -

February 23, 2021: Library Board Meeting Packet

Subject: Library Board Meeting Date: February 23, 2021 Time: 9:30 am Place: Online Only Zoom Meeting from Duncan Public Library 1. Call to Order with flag salute and prayer. 2. Read minutes from December 22, 2020, meeting. Approval. 3. Presentation of library statistics for December & January. 4. Presentation of library claims for December. Consider approval. 5. Presentation of library claims for January. Consider approval. 6. Director’s report a. Genealogy library update b. Friends annual meeting c. 100 years updates 7. Consider list of withdrawn items. Library staff recommends the listed items be declared surplus and be donated to the Friends of the Library for resale, and the funds be used to support the library. 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Comments a. By the library staff b. By the library board c. By the public 11. Adjourn Notice of Public Meeting DUNCAN PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD Date: Tuesday, February 23, 2021 Time: 9:30am Place: Video Conference AGENDA 1. Call to Order with flag salute and prayer. 2. Read minutes from December 22, 2020, meeting. Approval. 3. Presentation of library statistics for December & January. 4. Presentation of library claims for December. Consider approval. 5. Presentation of library claims for January. Consider approval. 6. Director’s report 7. Consider list of withdrawn items. Library staff recommends the listed items be declared surplus and be donated to the Friends of the Library for resale, and the funds be used to support the library. 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Comments a. By the library staff b. By the library board c. -

Viewers, Some of Whom Were Family from Across the Globe Who Otherwise Would Not Have Been Able to See Their Loved Ones Graduate

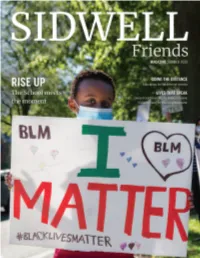

SIDWELL Contents FRIENDS MAGAZINE Summer 2020 Volume 91 Number 3 EDITORIAL DEPARTMENTS Editor-in-Chief Sacha Zimmerman 2 REFLECTIONS FROM THE HEAD OF SCHOOL Art Director 4 ON CAMPUS Meghan Leavitt The School announces the 2020 Newmyer Award Senior Writers honorees; the robotics team tackles 3D-printed masks; Natalie Champ we ask Director of Health Services Jasmin Whitfield five THIS YEAR, Kristen Page questions; local sports maven Chad Ricardo hosts the Alumni Editors School’s Athletic Celebration; and much more. Emma O’Leary 16 THE ARCHIVIST Anna Wyeth 04 EVERYTHING Thomas Sidwell knew how to handle a plague—or three. Contributing Writers Loren Hardenbergh 36 ALUMNI ACTION Caleb Morris New grads ascend to alumni status; Founder’s Day brings CHANGED. Contributing Photographers out alumni for the Let Your Life Speak series. Kelley Lynch Susie Shaffer ’69 40 FRESH INK And when it did, the power of the collective Freed Photography Brett Dakin ’94; Laurence Aurbach ’81; generosity of the Sidwell Friends community Digital Producers Anthony Silard ’85; Ellen Hopman ’70. became even more apparent. Anthony La Fleur 43 CLASS NOTES Sarah Randall Annual Fund donors provided teachers with the ability Spoiler alert: Everyone is sheltering in place. LEADERSHIP to quickly adapt and connect with students over new 18 83 WORDS WITH FRIENDS technologies. You ensured that every student had the Head of School “A Social-Distancing Puzzle” resources to continue learning on new digital platforms. Bryan K. Garman Chief Communications Officer 84 LAST LOOK You enabled the School to quickly respond to families Hellen Hom-Diamond “Lose Yourself” who faced unprecedented financial hardship. -

(Don't) Wear Glasses: the Performativity of Smart Girls On

GIRLS WHO (DON'T) WEAR GLASSES: THE PERFORMATIVITY OF SMART GIRLS ON TEEN TELEVISION Sandra B. Conaway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Kristine Blair, Advisor Julie Edmister Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie Katherine Bradshaw © 2007 Sandra Conaway All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair, Advisor This dissertation takes a feminist view of t television programs featuring smart girls, and considers the “wave” of feminism popular at the time of each program. Judith Butler’s concept from Gender Trouble of “gender as a performance,” which says that normative behavior for a given gender is reinforced by culture, helps to explain how girls learn to behave according to our culture’s rules for appropriate girlhood. Television reinforces for intellectual girls that they must perform their gender appropriately, or suffer the consequences of being invisible and unpopular, and that they will win rewards for performing in more traditionally feminine ways. 1990-2006 featured a large number of hour-long television dramas and dramedies starring teenage characters, and aimed at a young audience, including Beverly Hills, 90210, My So-Called Life, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Freaks and Geeks, and Gilmore Girls. In most teen shows there is a designated smart girl who is not afraid to demonstrate her interest in math or science, or writing or reading. In lieu of ethnic or racial minority characters, she is often the “other” of the group because of her less conventionally attractive appearance, her interest in school, her strong sense of right and wrong, and her lack of experience with boys. -

Are Our Bridges Safe? Relation to a Weather Bank Rob- THURSDAY 8/9 Bery July Hannah Bunning/Gulf Breeze News 27

BUS A SCHEDULE W A R INSIDE ! D ● W The I N N I N BUS Here! G S 50¢ August 9, 2007 PAG E 1B Bank robber on the loose ■ Geronimo’s Outpost BY FRANKLIN HAYES opens Gulf Breeze News [email protected] ■ Party for Gulf Breeze Police say Bubba’s new they are narrowing in on a book & CD handful of suspects but no arrests have been WEEKEND made in Are our bridges safe? relation to a Weather bank rob- THURSDAY 8/9 bery July Hannah Bunning/Gulf Breeze News 27. Lt. Rick Suspect Iso.T-Storms The Garcon Point Bridge was built in 1999 after three years of construction. Hawthorne O high 92 with the police department O BY VICI PAPAJOHN Breeze is dependent upon the Three Mile The answers to these questions are not low 78 Gulf Breeze News Bridge, the Garcon Point Bridge and the readily available. Though the Florida said their investigators, [email protected] Bob Sikes Bridge for transport to the main- Department of Transportation (FDOT) is with help from the Federal FRIDAY 8/10 land and beaches. How safe are our area tasked with the responsibility of assessing Bureau of Investigations Scat. T-Storms In the wake of the highly publicized dev- bridges? If cars can tumble like plastic toys the structural and functional integrity of and the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, are O astation of a crumbling, Minneapolis from the Minnesota span and fall 60 feet Florida’s bridges, the data is now controlled high 91 getting close to a possible O interstate bridge that spanned the into the Mississippi River, how safe are by the Homeland Security Administration. -

Comedy's Dynamic Duo, Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg

The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 108: Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg Show notes and links at tim.blog/podcast Tim Ferriss: Hello ladies and germs. This is Tim Ferriss and welcome to another episode of the Tim Ferriss show, where each episode it is my job to deconstruct world class performers, to tease out the habits, routines, morning rituals, favorite books, etc., that have made them spectacularly good at what they do. And there are patterns that you notice across disciplines. That is why I interview people from a very broad spectrum of areas, like the military, entertainment, chess, sports, comedy, etc. So it ranges from Arnold Schwarzenegger to General Stanley McChrystal and now, in this episode, we have a dynamic duo. We have Seth Rogen, @sethrogen, R-O-G-E-N, who is an actor, writer, producer and director and his partner in crime, Evan Goldberg, @evandgolberg on the Twitters, who is a Canadian director, screenwriter and producer. Together, they get into a whole lot of mischief and create some amazing comedy. I had a chance to spend some time with both these great gents, as well as their team, which was spectacular. And I won’t mention the location in case we’re keeping that quiet, but here’s some background. They’ve collaborated on films such as Superbad, which they actually first conceived of as teenagers, Knocked Up, Pineapple Express, The Green Hornet, and Funny People. They’ve also written for David: Ali G Show and The Simpsons. In 2013, Evan and Seth released their directorial debut, This is the End, which is actually a combination of two different ideas, and we get into that in the conversation. -

2011 Sundance Film Festival Announces Jury Members

For Immediate Release Media Contacts: January 17, 2011 Amy McGee (310) 360-1981 [email protected] 2011 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES JURY MEMBERS Sundance Alum Tim Blake Nelson to Host 2011 Sundance Film Festival Awards Ceremony on January 29 Susanne Bier, Jeffrey Blitz, America Ferrera, Matt Groening, Clark Gregg, Bong Joon-Ho, Jose Padilha, Kim Peirce, Jason Reitman, and Lucy Walker Among This Year’s Jurors Park City, UT— Sundance Institute today announced members of five juries awarding prizes at the upcoming Sundance Film Festival which runs January 20-30, 2011. The juries are comprised of 23 individuals spanning the global arts community. Juror photos and extended biographies, in addition to the complete Festival lineup and schedule, are available at www.sundance.org/festival. All awards will be announced the evening of January 29 at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival Awards Ceremony. The Short Film Awards will also be named earlier at a ceremony on Tuesday, January 25 at Park City’s Jupiter Bowl. The 2011 Sundance Film Festival Awards will be hosted by Tim Blake Nelson at the Basin Recreation Field House in Park City, Utah. Nelson has appeared in more than thirty films including The Incredible Hulk, Meet the Fockers, Syriana, The Good Girl, Minority Report, The Thin Red Line, and O Brother Where Art Thou? Nelson has a long history with Sundance Institute as both a Fellow and an Advisor at the Feature Film Program’s Directors and Screenwriting Labs. He made his directorial debut at the 1997 Sundance Film Festival with Eye of God, and has attended the Festival multiple times as a director, actor and panelist. -

“The Melissa Mccarthy Effect”: Feminism, Body

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School “THE MELISSA MCCARTHY EFFECT”: FEMINISM, BODY REPRESENTATION AND WOMEN-CENTERED COMEDIES A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Catherine Bednarz © 2020 Catherine Bednarz Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 ii The dissertation of Catherine Bednarz was reviewed and approved by the following: Matthew P. McAllister Professor of Communications Chair of Graduate Programs Dissertation Adviser Co-Chair of Committee Michelle Rodino-Colocino Associate Professor of Communications Co-Chair of Committee Kevin Hagopian Teaching Professor of Communications Lee Ahern Associate Professor of Communications iii Abstract Immediately following its release in 2011, Bridesmaids was met with enormous critical praise as a woman-centered and feminist comedy. This praise was due to the largely female cast of characters in a major film comedy, a rarity in Hollywood. Women face sexism at every level of Hollywood, especially in comedy, so the success of a woman-led movie within the comedy genre was significant. Reviewers described the triumph of Bridesmaids as a game changer, claiming it would open the door to other woman-fronted comedies. This potential was labeled the “Bridesmaids Effect” (Friendly, 2011) by reviewers. However, while some comediennes may have benefitted from the success, I argue that the influence may be more accurately described as a “Melissa McCarthy” effect. This is particularly significant because though there have been several notable and successful female comedians before Melissa McCarthy, very few would be considered fat and feminist. The presence of fat women is not accurately reflected in mass media (Henerson, 2001).