(Don't) Wear Glasses: the Performativity of Smart Girls On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama Courtney Watson, Ph.D. Radford University Roanoke, Virginia, United States [email protected] ABSTRACT Cultural movements including #TimesUp and #MeToo have contributed momentum to the demand for and development of smart, justified female criminal characters in contemporary television drama. These women are representations of shifting power dynamics, and they possess agency as they channel their desires and fury into success, redemption, and revenge. Building on works including Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, dramas produced since 2016—including The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, and Killing Eve—have featured the rise of women who use rule-breaking, rebellion, and crime to enact positive change. Keywords: #TimesUp, #MeToo, crime, television, drama, power, Margaret Atwood, revenge, Gone Girl, Orange is the New Black, The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, Killing Eve Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 37 Watson From the recent popularity of the anti-heroine in novels and films like Gone Girl to the treatment of complicit women and crime-as-rebellion in Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale to the cultural watershed moments of the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, there has been a groundswell of support for women seeking justice both within and outside the law. Behavior that once may have been dismissed as madness or instability—Beyoncé laughing wildly while swinging a baseball bat in her revenge-fantasy music video “Hold Up” in the wake of Jay-Z’s indiscretions comes to mind—can be examined with new understanding. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Jude Akuwudike

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Jude Akuwudike Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian Smyth +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Role Director Production Company Delroy Grant (The Night MANHUNT Marc Evans ITV Studios Stalker) PLEBS Agrippa Sam Leifer Rise Films/ITV2 MOVING ON Dr Bello Jodhi May LA Productions/BBC THE FORGIVING EARTH Dr Busasa Hugo Blick BBC/Netflix CAROL AND VINNIE Ernie Dan Zeff BBC IN THE LONG RUN Uncle Akie Declan Lowney Sky KIRI Reverend Lipede Euros Lyn Hulu/Channel 4 THE A WORD Vincent Sue Tully Fifty Fathoms/BBC DEATH IN PARADISE Series 6 Tony Simon Delaney Red Planet/BBC CHEWING GUM Series 2 Alex Simon Neal Retort/E4 FRIDAY NIGHT DINNER Series 4 Custody Sergeant Martin Dennis Channel 4 FORTITUDE Series 2 & 3 Doctor Adebimpe Hettie Macdonald Tiger Aspect/Sky Atlantic LUCKY MAN Doctor Marghai Brian Kelly Carnival Films/Sky 1 UNDERCOVER Al James Hawes BBC CUCUMBER Ralph Alice Troughton Channel 4 LAW & ORDER: UK Marcus Wright Andy Goddard Kudos Productions HOLBY CITY Marvin Stewart Fraser Macdonald BBC Between Us (pty) Ltd/Precious THE NO.1 LADIES DETECTIVE AGENCY Oswald Ranta Charles Sturridge Films MOSES JONES Matthias Michael Offer BBC SILENT WITNESS Series 11 Willi Brendan Maher BBC BAD GIRLS Series 7 Leroy Julian Holmes Shed Productions for ITV THE LAST DETECTIVE Series 3 Lemford Bradshaw David Tucker Granada HOLBY CITY Derek Fletcher BBC ULTIMATE FORCE Series 2 Mr Salmon ITV SILENT WITNESS: RUNNING ON -

18-Cr-204(Ngg)

Case 1:18-cr-00204-NGG-VMS Document 138 Filed 09/18/18 Page 1 of 4 PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK X UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, MEMORANDUM & ORDER -against- 18-CR-204(NGG) KEITH RANIERE, ALLISON MACK,CLARE BRONFMAN,KATHY RUSSELL,LAUREN SALZMAN, AND NANCY SALZMAN, Defendants. X NICHOLAS G. GARAUFIS, United States District Judge. Defendants Keith Raniere, Allison Mack, Clare Bronfman, Kathy Russell, Lauren Salzman, and Nancy Salzman have been indicted on charges arising from their participation in Nxivm, an organization that was allegedly a criminal enterprise. (Superseding Indictment(Dkt. 50) 1-40.) At a status conference on September 13, 2018, the Government moved to designate this case as complex pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 3161(h)(7)(B)(ii). tSee Tr. of Sept. 13, 2018, Hr'g ("Hr'g Tr.")(Dkt. Number Pending)4:24; Sept. 11,2018, Gov't Letter (Dkt. 129) at 3-4.) All Defendants oppose the Government's motion. (See Sept. 12, 2018, Defs. Letter (Dkt. 131) at 1.) For the following reasons, the court GRANTS the Government's motion and designates this case as complex. I. DISCUSSION "The Speedy Trial Act requires that a defendant be tried within seventy days of the unsealing ofthe indictment or his initial appearance before a judicial officer, whichever occurs later." United States v. Naseer. 38 F. Supp. 3d 269,275 (E.D.N.Y. 2014)(citing 18 U.S.C. § 3161(c)(1)). This seventy-day period is flexible. Id Courts may, for various reasons, exclude certain periods of time from the calculation of the speedy trial period. -

OMC | Data Export

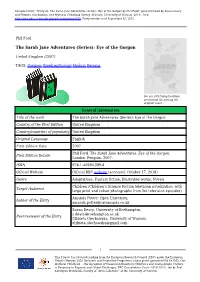

Amanda Potter, "Entry on: The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon by Phil Ford", peer-reviewed by Susan Deacy and Elżbieta Olechowska. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/550. Entry version as of September 25, 2021. Phil Ford The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon United Kingdom (2007) TAGS: Gorgons Greek mythology Medusa Perseus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon Country of the First Edition United Kingdom Country/countries of popularity United Kingdom Original Language English First Edition Date 2007 Phil Ford. The Sarah Jane Adventures: Eye of the Gorgon. First Edition Details London: Penguin, 2007. ISBN 978-1-40590-399-8 Official Website Official BBC website (accessed: October 17, 2018) Genre Adaptations, Fantasy fiction, Illustrated works, Novels Children (Children’s Science Fiction television novelization, with Target Audience large print and colour photographs from the television episodes) Amanda Potter, Open University, Author of the Entry [email protected] Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, [email protected] Peer-reviewer of the Entry Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. -

UC Merced UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal

UC Merced UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal Title Gender, Sexuality, and Inter-Generational Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/29q2t238 Journal UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal, 8(2) Author Abidia, Layla Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/M482030778 Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Gender, Sexuality, and Inter-Generational Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Layla Abidia University of California, Merced Author Notes: Questions and comments can be address to [email protected] 1 Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Abstract Hmong American men and women face social and cultural struggles where they are expected to adhere to Hmong requirements of gender handed down to them by their parents, and the expectations of the country they were born in. The consequence of these two expectations of contrasting values results in stress for everyone involved. Hmong parents are stressed from not having a secure hold on their children in a foreign environment, with no guarantee that their children will follow a “traditional” route. Hmong American men are stressed from growing up in a home environment that grooms them to be a focal point of familial attention based on gender, with the expectation that they will eventually be responsible for an entire family; meanwhile, they are living in this American national environment that stresses that the ideal is that gender is irrelevant in the modern world. Hmong American women are stressed and in turn hold feelings of resentment that they are expected to adhere to traditional familial roles by their parents in addition to following a path to financial success the same as men. -

THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’S Original Love Story by David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin

PRESS RELEASE IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE Twitter | @ModerateSoprano Facebook | @TheModerateSoprano Website | www.themoderatesoprano.com Playful Productions presents Hampstead Theatre’s THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’s Original Love Story By David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin LAST CHANCE TO SEE DAVID HARE’S THE MODERATE SOPRANO AS CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED WEST END PRODUCTION ENTERS ITS FINAL FIVE WEEKS AT THE DUKE OF YORK’S THEATRE. STARRING OLIVIER AWARD WINNING ROGER ALLAM AND NANCY CARROLL AS GLYNDEBOURNE FOUNDER JOHN CHRISTIE AND HIS WIFE AUDREY MILDMAY. STRICTLY LIMITED RUN MUST END SATURDAY 30 JUNE. Audiences have just five weeks left to see David Hare’s critically acclaimed new play The Moderate Soprano, about the love story at the heart of the foundation of Glyndebourne, directed by Jeremy Herrin and starring Olivier Award winners Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll. The production enters its final weeks at the Duke of York’s Theatre where it must end a strictly limited season on Saturday 30 June. The previously untold story of an English eccentric, a young soprano and three refugees from Germany who together established Glyndebourne, one of England’s best loved cultural institutions, has garnered public and critical acclaim alike. The production has been embraced by the Christie family who continue to be involved with the running of Glyndebourne, 84 years after its launch. Executive Director Gus Christie attended the West End opening with his family and praised the portrayal of his grandfather John Christie who founded one of the most successful opera houses in the world. First seen in a sold out run at Hampstead Theatre in 2015, the new production opened in the West End this spring, with Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll reprising their original roles as Glyndebourne founder John Christie and soprano Audrey Mildmay. -

![Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4839/sexuality-is-fluid-1-a-close-reading-of-the-first-two-seasons-of-the-series-analysing-them-from-the-perspectives-of-both-feminist-theory-and-queer-theory-264839.webp)

Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory

''Sexuality is fluid''[1] a close reading of the first two seasons of the series, analysing them from the perspectives of both feminist theory and queer theory. It or is it? An analysis of television's The L Word from the demonstrates that even though the series deconstructs the perspectives of gender and sexuality normative boundaries of both gender and sexuality, it can also be said to maintain the ideals of a heteronormative society. The [1]Niina Kuorikoski argument is explored by paying attention to several aspects of the series. These include the series' advertising both in Finland and the ("Seksualność jest płynna" - czy rzeczywiście? Analiza United States and the normative femininity of the lesbian telewizyjnego "The L Word" z perspektywy płci i seksualności) characters. In addition, the article aims to highlight the manner in which the series depicts certain characters which can be said to STRESZCZENIE : Amerykański serial telewizyjny The L Word stretch the normative boundaries of gender and sexuality. Through (USA, emitowany od 2004) opowiada historię grupy lesbijek this, the article strives to give a diverse account of the series' first two i biseksualnych kobiet mieszkających w Los Angeles. Artykuł seasons and further critical discussion of The L Word and its analizuje pierwsze dwa sezony serialu z perspektywy teorii representations. feministycznej i teorii queer. Chociaż serial dekonstruuje normatywne kategorie płci kulturowej i seksualności, można ______________________ również twierdzić, że podtrzymuje on ideały heteronormatywnego The analysis in the article is grounded in feminist thinking and queer społeczeństwa. Przedstawiona argumentacja opiera się m. in. na theory. These theoretical disciplines provide it with two central analizie takich aspektów, jak promocja serialu w Finlandii i w USA concepts that are at the background of the analysis, namely those of oraz normatywna kobiecość postaci lesbijek. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Summer of Produced by the Town of Huntington / Presented by the Huntington Arts Council from the Executive Director Arts Cultural News Our Way Through These Times

NONPROFIT ORG NONPROFIT ORG US POSTAGE US POSTAGE PAID PAID HUNTINGTON NY 11743 HUNTINGTON NY 11743 – PERMIT NO. 275 SUMMER 2020 (JUN–SEPT) • VOL XX • ISSUE 2 PERMIT NO. 275 *************ECRWSS POSTAL CUSTOMER FREE HUNTINGTON Summer of Produced by the Town of Huntington / Presented by the Huntington Arts Council From the Executive Director Arts Cultural News our way through these times. artistic landscape. Plans for the CTLE Cultural Arts Workshops for Teachers are In this Summer of Hope, our normal plans WINTER/SPRING 2020 in place for the fall. These workshops have not been viable. We are continuing are opportunities for teachers to expand to adapt and rethink to appropriately knowledge and gain valuable teaching and successfully continue to offer Table of Contents ideas and techniques through cultural services to the Long Island community. arts programs. Our gallery is adapting 5 Huntington Summer We had a fantastic 42 evening Summer to continue to present the excellent of Hope Arts Festival planned with a lineup of works from our community. We have 8-9 HAC Gallery Events performers across all genres. It is so showcased our artists using many virtual 10 Grants unfortunate that we are unable to bring techniques, including our website and an 12 Calendar of Events these to you. This summer would have increased social media presence. been the 55th anniversary of the festival, and the decision to cancel was painful. Marc Courtade The staff and board of HAC have been Executive Director We thank our partners at the Town of working tirelessly to evaluate all Huntington Arts Council Huntington for all of their assistance possible scenarios for the future of Visit Our Gallery and patience through an ever changing our 2020 programs. -

Alyson Hannigan Listing by Ren Smith Featured in USA Today

Alyson Hannigan listing by Ren Smith featured in USA Today February 14, 2018 Alyson Hannigan has a genius way of keeping organized at home Alyson Hannigan is giving us serious inspiration. Having trouble keeping your family’s schedule organized? Steal this fun DIY idea from actress Alyson Hannigan. The “How I Met Your Mother” star recently put her Santa Monica, California house up for sale, and we noticed a large chalkboard calendar on one of the walls in the kitchen area. It made us immediately want to grab a bucket of chalkboard paintand some wood to create one like it in our own homes. The wall features five rows of seven squares separated by narrow strips of wood. Along the top of the larger frame that surrounds the calendar are the names of the days of the week. Each box can be numbered with chalk according to the current month. It’s the perfect place to write down appointment reminders, your kids’ sports practice schedules and even menu plans for the week. And when you want to keep track of miscellaneous things — such as future vacation countdowns, phone numbers, or notes to family members — there’s a larger square on the side for that. The wall can easily be re-created with a few supplies from a home improvement store, and there are also so many variations you can do, such as using whiteboard paint as the base or creating the frame and boxes with Washi tape if you don’t want to work with wood. Hannigan, who has two young daughters, told People in 2016 that she loves to craft so much, she turned her guest house into a crafting room. -

Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing

Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing Directors Tell the Story Master the Craft of Television and Film Directing Bethany Rooney and Mary Lou Belli AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK © 2011 Bethany Rooney and Mary Lou Belli. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.