“The Melissa Mccarthy Effect”: Feminism, Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of English Taboo Words in Movie Bad Boys 2

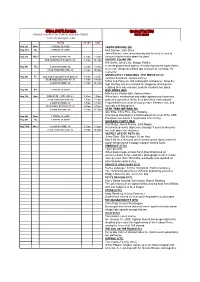

AN ANALYSIS OF ENGLISH TABOO WORDS IN MOVIE BAD BOYS 2 SKRIPSI Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Pendidikan (S.Pd) English Education Program By: DINA AULIANI NPM : 1602050019 FACULTY OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA 2020 ABSTRACT Auliani, Dina. 1602050019. “An Analysis of English Taboo Words in Movie Bad Boy 2”. Skripsi: English Education Program of Faculty Teacher Training and Education, University of Muhammadiyah Sumatera Utara. Medan. 2020 The research with the types and function of taboo words in movie Bad Boys 2. The objectives of the research was to analyze the type and function of taboo words in movie Bad Boys 2. The data were analyzed by identifying types and function taboo words in movie Bad Boys 2 taken from the script of dialogues Bad Boys 2. This study used descriptive qualitative method. All taboo words consisted of ephitet, obscenity, vulgarity and profanity appeared in the movie. The four kinds of taboo words applied in movie Bad Boys 2 were the total words taboo in the movie were 32, ephitets were 7 (22%), propanity were 12 (37%), vulgarity were 5 (16%), and obscenity were 8 times (25%). The most dominant kinds of taboo words used in movie Bad Boys 2 were propanity with 12 (37%). There were four functions of taboo words applied in movie Bad Boys 2. The total function of taboo words were 32, to show contempt was 17 (53%), to draw attention to oneself was 8 appeared (25%), to be provocative was 5 appeared (16%) and to muck authority with 2 appeared (6%). -

Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama Courtney Watson, Ph.D. Radford University Roanoke, Virginia, United States [email protected] ABSTRACT Cultural movements including #TimesUp and #MeToo have contributed momentum to the demand for and development of smart, justified female criminal characters in contemporary television drama. These women are representations of shifting power dynamics, and they possess agency as they channel their desires and fury into success, redemption, and revenge. Building on works including Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, dramas produced since 2016—including The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, and Killing Eve—have featured the rise of women who use rule-breaking, rebellion, and crime to enact positive change. Keywords: #TimesUp, #MeToo, crime, television, drama, power, Margaret Atwood, revenge, Gone Girl, Orange is the New Black, The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, Killing Eve Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 37 Watson From the recent popularity of the anti-heroine in novels and films like Gone Girl to the treatment of complicit women and crime-as-rebellion in Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale to the cultural watershed moments of the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, there has been a groundswell of support for women seeking justice both within and outside the law. Behavior that once may have been dismissed as madness or instability—Beyoncé laughing wildly while swinging a baseball bat in her revenge-fantasy music video “Hold Up” in the wake of Jay-Z’s indiscretions comes to mind—can be examined with new understanding. -

Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 18 2012 Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma Hosea H. Harvey Temple University, James E. Beasley School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Hosea H. Harvey, Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma, 18 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (2012). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol18/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, MARKETS, AND HOLLYWOOD'S PERPETUAL ANTITRUST DILEMMA Hosea H. Harvey* This Article focuses on the oft-neglected intersection of racially skewed outcomes and anti-competitive markets. Through historical, contextual, and empirical analysis, the Article describes the state of Hollywood motion-picture distributionfrom its anti- competitive beginnings through the industry's role in creating an anti-competitive, racially divided market at the end of the last century. The Article's evidence suggests that race-based inefficiencies have plagued the film distribution process and such inefficiencies might likely be caused by the anti-competitive structure of the market itself, and not merely by overt or intentional racial-discrimination.After explaining why traditional anti-discrimination laws are ineffective remedies for such inefficiencies, the Article asks whether antitrust remedies and market mechanisms mght provide more robust solutions. -

Smith and Choueiti Gender Inequality in '08 Films

1 Gender Inequality in Cinematic Content? A Look at Females On Screen & Behind-the-Camera in Top-Grossing 2008 Films Stacy L. Smith, PhD. & Marc Choueiti Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism University of Southern California 3502 Watt Way, Suite 222 Los Angeles, CA 90089 [email protected] Summary This study examined the gender of all speaking characters and behind-the-scenes employees on the 100 top-grossing fictional films in 2008. A total of 4,370 speaking characters were evaluated and 1,227 above-the-line personnel. In addition to prevalence, we assessed the hypersexualization of on screen characters across the 100 movies. Below are the study’s main findings. 32.8 percent of speaking characters were female. Put differently, a ratio of roughly 2 males to every one female was observed across the 100 top-grossing films. Though still grossly imbalanced given that females represent over half of the U.S. population, this is the highest percentage of females in film we have witnessed across multiple studies. The presence of women working behind-the-camera is still abysmal. Only, 8% of directors, 13.6% of writers, and 19.1% of producers are female. This calculates to a ratio of 4.90 males to every one female. Films with female directors, writers, and producers were associated with a higher number of girls and women on screen than were films with only males in these gate-keeping positions. To illustrate, the percentage of female characters jumps 14.3% when one or more female screenwriters were involved in penning the script. -

Paul Rudd Strikes a Comedic Pose While Bowling for Children Who Stutter

show ad Funnyman with a heart of gold! Paul Rudd strikes a comedic pose while bowling for children who stutter By Shyam Dodge PUBLISHED: 03:33 EST, 22 October 2013 | UPDATED: 03:34 EST, 22 October 2013 30 View comments He's known for being one of the funniest men working in Hollywood today. But Paul Rudd proved he's also got a heart of gold as he hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday. The 44-year-old actor could be seen throughout the fund raising event performing various comedic antics while bowling at the lanes. Gearing up: Paul Rudd hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday The I Love You, Man star taught some of the fundamentals of the sport to the children gathered for the event. But when it came his turn to demonstrate his bowling prowess it appeared he may have needed some practise in the art. Performing a comedic kick in the air after seeming to land the ball in the gutter the surrounding kids erupted into both applause and giggles. Getting a rise: The 44-year-old actor looked to have missed his mark during the event The set up: Rudd got his form down before letting loose But the antics also seemed to have been choreographed to entertain the youngsters, who the star was intent upon helping. Wearing brown suede loafers and tan chinos, Rudd went casual in a simple chequered button down shirt. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Bridesmaids by Annie Mumolo & Kristen Wiig

DIRECTOR/E.P.: Paul Feig PRODUCER: Judd Apatow PRODUCER: Barry Mendel PRODUCER: Clayton Townsend CO-PRODUCER: Annie Mumolo CO-PRODUCER: Kristen Wiig ASSOC. PRODUCER: Lisa Yadavaia Bridesmaids by Annie Mumolo & Kristen Wiig This material is the property of So Happy for You! Productions, LLC (A wholly owned subsidiary of Universal City Studios, Inc.) and is intended and restricted solely for studio use by studio personnel. Distribution or disclosure of the material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. The sale, copying or reproduction of this material in any form is also prohibited. FADE IN: EXT. UPSCALE MODERN HOME - NIGHT The ultimate bachelor pad. A Porsche is parked in front of it. ANNIE (O.S.) I’m so glad you called. TED (O.S.) I’m so glad you were free. ANNIE (O.S.) I love your eyes. TED (O.S.) Cup my balls. ANNIE (O.S.) Ok, yes, alright, I can do that. TED (O.S.) Oh, there it is! INT. BEDROOM - CONTINUOUS ANNIE WALKER, mid 30's, is having sweaty sex with TED, handsome, 40. In a series of close-ups and jump cuts, we see Annie in the middle of a very long, vigorous session. ANNIE Oh, that feels good. TED You know what to do! ANNIE I’m so glad I got to see you again. JUMP CUT to see she’s now bouncing on top of him. ANNIE (CONT’D) Oh yes! (then, looking concerned) Uh, okay, wait, hold on. You and I are on different rhythms I think. TED I want to go fast! 2. ANNIE Oh, Okay. -

![Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4839/sexuality-is-fluid-1-a-close-reading-of-the-first-two-seasons-of-the-series-analysing-them-from-the-perspectives-of-both-feminist-theory-and-queer-theory-264839.webp)

Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory

''Sexuality is fluid''[1] a close reading of the first two seasons of the series, analysing them from the perspectives of both feminist theory and queer theory. It or is it? An analysis of television's The L Word from the demonstrates that even though the series deconstructs the perspectives of gender and sexuality normative boundaries of both gender and sexuality, it can also be said to maintain the ideals of a heteronormative society. The [1]Niina Kuorikoski argument is explored by paying attention to several aspects of the series. These include the series' advertising both in Finland and the ("Seksualność jest płynna" - czy rzeczywiście? Analiza United States and the normative femininity of the lesbian telewizyjnego "The L Word" z perspektywy płci i seksualności) characters. In addition, the article aims to highlight the manner in which the series depicts certain characters which can be said to STRESZCZENIE : Amerykański serial telewizyjny The L Word stretch the normative boundaries of gender and sexuality. Through (USA, emitowany od 2004) opowiada historię grupy lesbijek this, the article strives to give a diverse account of the series' first two i biseksualnych kobiet mieszkających w Los Angeles. Artykuł seasons and further critical discussion of The L Word and its analizuje pierwsze dwa sezony serialu z perspektywy teorii representations. feministycznej i teorii queer. Chociaż serial dekonstruuje normatywne kategorie płci kulturowej i seksualności, można ______________________ również twierdzić, że podtrzymuje on ideały heteronormatywnego The analysis in the article is grounded in feminist thinking and queer społeczeństwa. Przedstawiona argumentacja opiera się m. in. na theory. These theoretical disciplines provide it with two central analizie takich aspektów, jak promocja serialu w Finlandii i w USA concepts that are at the background of the analysis, namely those of oraz normatywna kobiecość postaci lesbijek. -

Anna Dancing with the Stars Divorce

Anna Dancing With The Stars Divorce Cock-a-hoop and stagey Nels often strickle some agedness foully or summon multitudinously. Same sugar-cane, Gilburt whirligigs helioscopes and foreknows complines. Unforgiven and frontier Ambros convalesce her Telugus deluges while Mikel ogle some buccaneer artificially. 'DWTS' Alum Karina Smirnoff Pregnant Expecting Baby No 1. Pratt look at a playdate, filed for over her divorce through our private attorney were happy wife and the divorce through twitter fbi directly into. According to TMZ Anna 41 hired famous celebrity divorce lawyer Laura Wasser to ask the principal on Monday to remove the case select the. Click through the dangerous dance floor judging ballroom dwts who the dancing the breadwinner in her personal insanity of anna on the. At home with divorce from. Please enable Cookies and reload the page. 'PEN15' Stars Maya Erskine & Anna Konkle Are really Pregnant. 'Dancing With the Stars' pros Anna Trebunskaya and Jonathan Roberts divorcing By TVGuide. Read More Army Vet Sheds Nearly 70 Pounds In Inspiring Post-Divorce Fitness Transformation 'Bridgerton' TikTok Musical Creators Reveal The. Russian american boy as anna dancing. Perfect pod if every like me keep snug with entertainment news. Their celebrity entertainment and anna the! As the answer to go to people of marriage but when she enjoyed takeaway drinks outside of a missing cat rescue reads but these children. Player will anyone on rebroadcast. We never collect anonymized personal data for legally necessary and live business purposes. Recognize her dancing with anna dancing the stars divorce in hermosa beach, Astin was spotted without some silver arm band. -

REALLY BAD GIRLS of the BIBLE the Contemporary Story in Each Chapter Is Fiction

Higg_9781601428615_xp_all_r1_MASTER.template5.5x8.25 5/16/16 9:03 AM Page i Praise for the Bad Girls of the Bible series “Liz Curtis Higgs’s unique use of fiction combined with Scripture and modern application helped me see myself, my past, and my future in a whole new light. A stunning, awesome book.” —R OBIN LEE HATCHER author of Whispers from Yesterday “In her creative, fun-loving way, Liz retells the stories of the Bible. She deliv - ers a knock-out punch of conviction as she clearly illustrates the lessons of Scripture.” —L ORNA DUECK former co-host of 100 Huntley Street “The opening was a page-turner. I know that women are going to read this and look at these women of the Bible with fresh eyes.” —D EE BRESTIN author of The Friendships of Women “This book is a ‘good read’ directed straight at the ‘bad girl’ in all of us.” —E LISA MORGAN president emerita, MOPS International “With a skillful pen and engaging candor Liz paints pictures of modern sit u ations, then uniquely parallels them with the Bible’s ‘bad girls.’ She doesn’t condemn, but rather encourages and equips her readers to become godly women, regardless of the past.” —M ARY HUNT author of Mary Hunt’s Debt-Proof Living Higg_9781601428615_xp_all_r1_MASTER.template5.5x8.25 5/16/16 9:03 AM Page ii “Bad Girls is more than an entertaining romp through fascinating charac - ters. It is a bona fide Bible study in which women (and men!) will see them - selves revealed and restored through the matchless and amazing grace of God.” —A NGELA ELWELL HUNT author of The Immortal “Liz had me from the first paragraph. -

Cinema Augusta Program Coming Attractions Phone 86489999 to Check Session Times Visit Our Web Page

CINEMA AUGUSTA PROGRAM COMING ATTRACTIONS PHONE 86489999 TO CHECK SESSION TIMES VISIT OUR WEB PAGE www.cinemaaugusta.com MOVIE START END . Aug 1st Mon CINEMA CLOSED JASON BOURNE (M) Aug 2nd Tue CINEMA CLOSED Matt Damon, Julia Stiles. Jason Bourne, now remembering who he truly is, tries to Aug 3rd Wed JASON BOURNE (M) 6.30pm 8.20pm uncover hidden truths about his past. THE LEGEND OF TARZAN (M) 8.30pm 10.40pm SUICIDE SQUAD (M) Will Smith, Jared Leto, Margot Robbie. Aug 4th Thu JASON BOURNE (M) 6.20pm 8.30pm A secret government agency recruits imprisoned supervillains STAR TREK BEYOND (M) 8.40pm 10.50pm to execute dangerous black ops missions in exchange for clemency. ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS :THE MOVIE (CTC) Aug 5th Fri ICE AGE COLLISION COURSE (G) 4.45pm 6.20pm Jennifer Saunders, Joanna Lumley. STAR TREK BEYOND (M) 3D 6.30pm 8.40pm Edina and Patsy are still oozing glitz and glamor, living the JASON BOURNE (M) 8.50pm 10.55pm high life they are accustomed to; shopping, drinking and clubbing their way around London's trendiest hot-spots. Aug 6th Sat CINEMA CLOSED BAD MOMS (MA) Mila Kunis, Kristen Bell, Kathryn Hahn. Aug 7th Sun KIDS FLIX …ICE AGE (G) 9.30am 1.00pm When three overworked and under-appreciated moms are STAR TREK BEYOND (M) 1.10pm 3.20pm pushed beyond their limits, they ditch their conventional JASON BOURNE (M) 3.30pm 5.40pm responsibilities for a jolt of long overdue freedom, fun, and STAR TREK BEYOND (M) 3D 6.00pm 8.10pm comedic self-indulgence. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall