Rīga Conference Papers 2016 This Riga Conference Companion Volume Offers Reflections on the Complex Developments and Fu- Ture of the Broader Trans-Atlantic Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sensory Ethnographic Study of Therapeutic Landscape Experiences of People Living with Dementia in the Wider Community

Out and About: A Sensory Ethnographic Study of Therapeutic Landscape Experiences of People Living with Dementia in the Wider Community By Rahena Qaailah Bibi Mossabir (MA) Faculty of Health and Medicine Lancaster University Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) September 2018 0 0 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is all my original work and I am the sole author. This work has not previously been published or presented for an award. All sources are acknowledged as References. It has been jointly funded by the Economics and Social Research Council and Age UK Lancaster. 1 ABSTRACT Whilst ageing in place is considered important for a healthier and a better quality of life for older people, there is yet a dearth of evidence on how older people with dementia negotiate and experience the wider community. The aim of the present study is therefore to explore experiences of social and spatial engagement in the wider community for people living with dementia in order to advance understandings of how their interactions in and with community settings impact on their health and wellbeing. Drawing on the theoretical framework of therapeutic landscapes and a sensory ethnographic methodology, I provide social, embodied and symbolic accounts of people’s everyday experiences and pursuits of health and wellbeing within their neighbourhood and beyond. An in-depth examination of socio-spatial interactions of nine people with dementia, seven of whom participated with family carers, is conducted by use of innovative interview methods (including photo-elicitation and walking interviews), participant observations and participant ‘diaries’ (kept for a period of four weeks). -

Place, Identity and Community Conflict in Mixed-Use Neighbourhoods: the Case of Kings Cross, Sydney

Place, identity and community conflict in mixed-use neighbourhoods: The case of Kings Cross, Sydney Ryan van den Nouwelant A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Built Environment in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 THE UNIVERSITYOF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: van den Nouwelant Firstname: Ryan Other name/s: Mark Abbreviation fordegree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: not applicable Faculty: Built Environment Title: Place, identity and community conflict in mixed-use neighbourhoods: the case of Kings Cross, Sydney Abstract This thesis examines the role of urban planning processes in managing community conflict. Mitigating community conflict is one of the central arguments for robust planning systems,so shortcomings need to be identified and understood. Usingthe case study of Kings Cross, Sydney, the research demonstrates how the planning concept of 'the mixed-use neighbourhood', and in particular its inherent contradictions, permeate into the construction of the identity of this particularneighbourhood. Through media analysis and a series of stakeholder interviews, these contradictions are shown to prevail beyond planning discourses, and that they are central to community conflicts in the case study. By framing community conflict as the contestation of the neighbourhood's identity, it is revealed that these conflicts do not always lie between social and economic objectives of planning policy (and so residents and businesses) as is assumed by many stakeholders. Instead, it is argued to lie between the underlying spatial dimensions to the constructed identity: whether the 'self-contained neighbourhood' or the 'well connected neighbourhood'. -

Ageing with Smartphones in Urban Italy

Ageing with Smartphones in Urban Italy Ageing with Smartphones in Urban Italy Care and community in Milan and beyond Shireen Walton First published in 2021 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Text © Author, 2021 Images © Author and copyright holders named in captions, 2021 The author has asserted her rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial Non- derivative 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC- ND 4.0). This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use provided author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Walton, S. 2021. Ageing with Smartphones in Urban Italy: Care and community in Milan and beyond. London: UCL Press. https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787359710 Further details about Creative Commons licences are available at http:// creativecommons.org/ licenses/ Any third- party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons licence unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. If you would like to reuse any third- party material not covered by the book’s Creative Commons licence, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 973- 4 (Hbk.) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 972- 7 (Pbk.) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 971- 0 (PDF) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 974- 1 (epub) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 975- 8 (mobi) DOI: https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787359710 Contents Chapter summaries vi List of figures xiii Series Foreword xvi Acknowledgements xviii 1. -

Thorpe Neighbourhood Plan Representations Summary

Summary of representations received by Runnymede Borough Council on the Thorpe Neighbourhood Plan 2015-2030 (Submission Plan - June 2020) as part of the Regulation 16 consultation (As submitted to the independent Examiner pursuant to paragraph 9 of Schedule 4B to the 1990 Act) Consultation dates: Tuesday 7th July - Tuesday 18th August 2020. Please note: All the original representation documents are included in the examination pack. The table below is a summary of the 11 representations received so will not be verbatim. Ref Consultee Summary of comment no. 1 Avison Young on behalf of • Confirmed that National Grid has no National Grid comments to make in response to this consultation. • National Grid indicated that it would help ensure the continued safe operation of existing sites and equipment and to facilitate future infrastructure investment. It also wishes to be involved in the preparation, alteration and review of plans and strategies which may affect their assets. Therefore, National Grid indicated that it ought to be consulted on any Development Plan Document (DPD) or site-specific proposals that could affect National Grid’s assets. 2 Highways England • Highways England have no comments. • However, Highways England indicated that the strategic road network (SRN) is a critical national asset which it works to ensure is operated and managed in the public interest. It will therefore be concerned with proposals that have the potential to impact the safe and efficient operation of the SRN, in this case the M25 and M3 motorways. 3 Natural England Natural England made the following comments to further strengthen the environmental policies in the Thorpe Neighbourhood Plan: • Natural England note that development within this Neighbourhood Plan will follow Runnymede Local Plan’s requirements for 1 both Thames Basin Heaths and South West London Waterbodies Special Protection Areas (SPAs). -

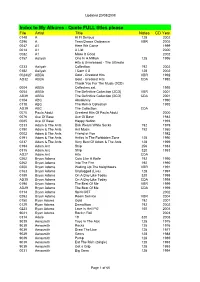

Album Backup List

Updated 20/08/2008 Index to My Albums - Quote FULL titles please File Artist Title Notes CD Year 0148 A Hi Fi Serious 128 2002 0296 A Teen Dance Ordinance VBR 2005 0047 A1 Here We Come 1999 0014 A1 A List 2000 0082 A1 Make It Good 2002 0157 Aaliyah One In A Million 128 1996 Hits & Unreleased - The Ultimate 0233 Aaliyah Collection 192 2002 0182 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 128 2002 0024/27 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits VBR 1992 AD32 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits CDA 1992 Thank You For The Music (3CD) 0004 ABBA Collectors set 1995 0054 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) VBR 2001 AB39 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) CDA 2001 0104 ABC Absolutely 1990 0118 ABC The Remix Collection 1993 AD39 ABC The Collection CDA 0070 Paula Abdul Greatest Hits Of Paula Abdul 2000 0076 Ace Of Base Ace Of Base 1983 0085 Ace Of Base Happy Nation 1993 0233 Adam & The Ants Dirk Wears White Socks 192 1979 0150 Adam & The Ants Ant Music 192 1980 0002 Adam & The Ants Friend or Foe 1982 0191 Adam & The Ants Antics In The Forbidden Zone 128 1990 0237 Adam & The Ants Very Best Of Adam & The Ants 128 1999 0194 Adam Ant Strip 256 1983 0315 Adam Ant Strip 320 1983 AD27 Adam Ant Hits CDA 0262 Bryan Adams Cuts Like A Knife 192 1990 0262 Bryan Adams Into The Fire 192 1990 0200 Bryan Adams Waking Up The Neighbours VBR 1991 0163 Bryan Adams Unplugged (Live) 128 1997 0189 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today 320 1998 AD30 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today CDA 1998 0198 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me VBR 1999 AD29 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me CDA 1999 0114 Bryan Adams Spirit OST 2002 0293 Bryan Adams -

Library Songs: Eine Compilation

__________________________________________________///LIBREAS. Library Ideas #13 | www.libreas.eu/ LIBRARY SONGS - EINE COMPILATION von Marc-Oliver Borgstedt „Libraries gave us power“ sangen die Manic Street Preachers in „A Design For Life” 1996, Britney Spears hüpfte zu Beginn ihrer Karriere gehüllt in hautenge Cardigans und mit überdimensionaler Brille auf der Nase durch die halbe Welt und im Video zu ihrem Hit „Everytime We Touch“ wirbelt die deutsche Dance-Formation Cascada viel Staub aus den alten Schinken einer imaginären Bibliothek. Dass Bibliotheken eine wichtige Projektionsfläche für die Pop-Kultur abgeben, steht außer Frage. Doch sind Bilder vom Streber, den erst wilde Eurodance-Beats hinter der Ausleihtheke hervorholen und ihn als indifferentes Sexobjekt vergewaltigen, nicht vereinbar mit dem neuen bibliothekarischen Selbst, das sich befreien möchte von der oberflächlichen Symbolik der Masse. Popkultur wohnt immer eine normative Kraft inne, wenn sie vorgibt, was sein soll. Mädchen in kur- zen Röcken und String-Tangas, die sich gerne mit ihrer besten Freundin zum Joggen verabreden, Jungs, die Anabolika getränkt und glatt rasiert in Proletensprache über die Nation reden, das ist die dialektische Ausgangslage, in der auch die Bibliothek ihre Rolle hat. Die Bibliothek 2.0 baut auf Com- puterspiele und egalitäre, deutsche Klänge, um sich beim Mainstream anzubiedern. Es ist der Ver- such, reformorientiert zu agieren, dabei das Bestehende zu bewahren, das letztlich nur aus einer längst erodierenden Mittelschicht besteht. Hier geht es jedoch nicht mehr um das emanzipative Po- tential der Bibliothek– Wir sind Helden sind genauso oberlehrerhaft bieder wie die Thekenbibliothek –, sondern um die Abschaffung einer Institution, die die Kids retten könnte. Wie schaut aber ein popkultureller Entwurf aus, der Bibliotheken und ihre Benutzer progressiv ver- bindet? Der in der New York Times beschriebene Stil der „Hipper Crowd of Shushers“ setzt bewusst auf akkurate Spießerrobe und geordnete Stylings aus längst vergessenen Zeiten. -

Remediating the Eighties: Nostalgia and Retro in British Screen Fiction from 2005 to 2011

REMEDIATING THE EIGHTIES: NOSTALGIA AND RETRO IN BRITISH SCREEN FICTION FROM 2005 TO 2011 Thesis submitted by Caitlin Shaw In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, March 2015 2 3 ABSTRACT This doctoral thesis studies a cycle of British film and television fictions produced in the years 2005-2011 and set retrospectively in the 1980s. In its identification and in-depth textual and contextual analysis of what it terms the ‘Eighties Cycle’, it offers a significant contribution to British film and television scholarship. It examines eighties- set productions as members of a sub-genre of British recent-past period dramas begging unique consideration outside of comparisons to British ‘heritage’ dramas, to contemporary social dramas or to actual history. It shows that incentives for depicting the eighties are wide-ranging; consequently, it situates productions within their cultural and industrial contexts, exploring how these dictate which eighties codes are cited and how they are textually used. The Introduction delineates the Eighties Cycle, establishes the project’s academic and historical basis and outlines its approach. Chapter 1 situates the work within the academic fields that inform it, briefly surveying histories and socio-cultural studies before examining and assessing existing scholarship on Eighties Cycle productions alongside critical literature on 1980s, 90s and contemporary British film and television; nostalgia and retro; modern media, history and memory; British and American period screen fiction; and transmedia storytelling. Chapter 2 considers how a selection of productions employing ‘the eighties’ as a visual and audio style invoke and assign meaning to commonly recognised aesthetic codes according to their targeted audiences and/or intended messages. -

"We're from the Favela but We're Not Favelados" the Intersection of Race, Space, and Violence in Northeastern Brazil

PhD thesis submission: abstract and declaration of word length This form should be submitted to the Research Degrees Unit with your thesis Name of candidate: Christopher M. Johnson Title of thesis:"We're from the favela but we're not favelados: Race, space and violence in northeastern Brazil Abstract The title-page should be followed by an abstract consisting of no more than 300 words. A copy of the abstract should be given below. This is required for publication in the ASLIB Index of Theses. In Salvador da Bahia's high crime/violence peripheral neighbourhoods, black youth are perceived as criminals levying high social costs as they attempt to acquire employment, enter university, or political processes. Low-income youth must overcome the reality of violence while simultaneously confronting the support, privileged urban classes have for stricter law enforcement and the clandestine acts of death squads. As youth from these neighbourhoods begin to develop more complex identities some search for alternative peer groups, social networks and social programmes that will guide them to constructive life choices while others consign themselves to options that are more readily available in their communities. Fast money and the ability to participate in the global economy beyond ‘passive’ engagement draws some youth into crime yet the majority choose other paths. Yet, the majority use their own identities to build constructive and positive lives and avoid involvement with gangs and other violent social groups. Drawing from Brazil's racial debates started by Gilberto Freyre, findings from this research suggest that while identity construction around race is ambiguous, specific markers highlight one's identity making it difficult to escape negative associations with criminality and violence. -

Értekezés a Doktori (Phd) Fokozat Megszerzése Érdekében Az Irodalomtudományok Tudományágban

SPACE, MOVEMENT AND IDENTITY IN CONTEMPORARY BRITISH ASIAN FICTION Értekezés a doktori (PhD) fokozat megszerzése érdekében az Irodalomtudományok tudományágban Írta: Pataki Éva okleveles angol nyelv és irodalom szakos bölcsész és tanár Készült a Debreceni Egyetem Irodalomtudományok doktori iskolája (Angol-amerikai irodalomtudományi programja) keretében Témavezető: Dr. Bényei Tamás ................................................................ (olvasható aláírás) A doktori szigorlati bizottság: elnök: Dr. ................................................................ tagok: Dr. ................................................................ Dr. ................................................................ A doktori szigorlat időpontja: 201................................................... Az értekezés bírálói: Dr. ................................................................ Dr. ................................................................ Dr. ................................................................ A bírálóbizottság: elnök: Dr. ............................................................... tagok: Dr. ............................................................... Dr. ............................................................... Dr. ............................................................... Dr. ............................................................... A nyilvános vita időpontja: 201………………………………….. Én, Pataki Éva, teljes felelősségem tudatában kijelentem, hogy a benyújtott értekezés önálló munka, a szerzői -

ENERGY and RESOURCE EFFICIENT URBAN NEIGHBOURHOOD DESIGN PRINCIPLES for TROPICAL COUNTRIES Practitioner’S Guidebook

ENERGY AND RESOURCE EFFICIENT URBAN NEIGHBOURHOOD DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR TROPICAL COUNTRIES Practitioner’s Guidebook ENERGY AND RESOURCE EFFICIENT URBAN NEIGHBOURHOOD i DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR TROPICAL COUNTRIES PRACTITIONER’S GUIDEBOOK ENERGY AND RESOURCE EFFICIENT URBAN NEIGHBOURHOOD DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR TROPICAL COUNTRIES A Practitioner’s Guidebook ii ENERGY AND RESOURCE EFFICIENT URBAN NEIGHBOURHOOD DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR TROPICAL COUNTRIES PRACTITIONER’S GUIDEBOOK ENERGY AND RESOURCE EFFICIENT URBAN NEIGHBOURHOOD DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR TROPICAL COUNTRIES A Practitioner’s Guidebook Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme 2018 United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) P. O. Box 30030, 00100 Nairobi GPO KENYA Tel: +254-020-7623120 (Central Office) www.unhabitat.org HS Number: HS/058/18E DISCLAIMER The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations con cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the United Nations, or its Member States. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Project supervisor: Vincent Kitio Principal author: Prof. Federico M. Butera, Politecnico of Milan, Italy. Contributors: UN-Habitat staff Eugenio Morello, Dept. Architecture and Urban Studies, Politecnico di Milano, for drafting background papers on “Minimising energy demand for transport” and “Design tips and Checklist”, and for contributing to the introduction. Maria Chiara Pastore, Dept. Architecture and Urban Studies, Politecnico di Milano, for drafting the background paper on “Case studies”. -

Made in Tepito: Urban Tourism and Inequality in Mexico City

Made in Tepito: Urban Tourism and Inequality in Mexico City Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München vorgelegt von Barbara Vodopivec aus Slowenien 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Eveline Dürr Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Martin Sökefeld Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 09.11.2017 For the people of Tepito, for their kindness and support Acknowledgments This thesis would not have been possible without the collaboration and support from the people I met in Mexico, especially in Tepito. I am truly honoured that so many of them took their time to talk to me, entrusting me with their ideas, perspectives and life stories. I have learned a great deal from our encounters – not merely in terms of academic knowledge but also in terms of personal ideas and world views. Since I have decided to use pseudonyms for my interlocutors in the thesis, I would like to express here my gratitude to the following people who greatly facilitated my stay in Tepito: Alfonso Hernández Hernández, Luis Arévalo Venegas, Veronica Matilde Hernández Hernández, Jacobo Noe Loeza Amaro, Marina Beltran, Jose Luis Rubio, Lourdes Ruíz, Mayra Valenzuela Rojas, Enriqueta Romero, Diego Sebastián Cornejo, David Rivera, Gabriel Sanchez Valverde, Eduardo Vásquez Uribe, Fernando César Ramírez, Everardo Pillado, Ariel Torres Ramirez, Oscar Delgado Olvera, Robert Galicia, Marcela Silvia Hernández Cortés, Maria Rosa Rangel, Gilberto Bueno, Lourdes Arévalo Anaya, Leticia Ponce, Salvador Gallardo, Mario Puga, Poncho Hernández Gómez, Julio César Laureani, Paulina Hernández y Marco Velasco. There are many other people I met in Mexico City who in one way or another helped me with my research and my orientation in this gigantic city, either with contacts, ideas or interesting conversations. -

Comparing the Cultures of Cities in Two European Capitals of Culture Claire Bullen

Comparing the Cultures of Cities in Two European Capitals of Culture Claire Bullen To cite this version: Claire Bullen. Comparing the Cultures of Cities in Two European Capitals of Culture. Etnofoor, Antrhropological Journal, 2016, The City, 28 (2), pp.99 - 120. hal-01491789 HAL Id: hal-01491789 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01491789 Submitted on 28 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Comparing the Cultures of Cities in Two European Capitals of Culture Author(s): Claire Bullen Source: Etnofoor, Vol. 28, No. 2, The City (2016), pp. 99-120 Published by: Stichting Etnofoor Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44013448 Accessed: 17-03-2017 11:02 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Stichting Etnofoor is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Etnofoor This content downloaded from 193.50.65.21 on Fri, 17 Mar 2017 11:02:32 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Comparing the Cultures of Cities in Two European Capitals of Culture Claire Bullen Aix Marseille University, cnrs, idemec Building on over a century of social science exploring city.