LR(0) Drawbacks Simple LR (SLR) SLR Parse LR(1) LR(1) Items LR(1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Validating LR(1) Parsers

Validating LR(1) Parsers Jacques-Henri Jourdan1;2, Fran¸coisPottier2, and Xavier Leroy2 1 Ecole´ Normale Sup´erieure 2 INRIA Paris-Rocquencourt Abstract. An LR(1) parser is a finite-state automaton, equipped with a stack, which uses a combination of its current state and one lookahead symbol in order to determine which action to perform next. We present a validator which, when applied to a context-free grammar G and an automaton A, checks that A and G agree. Validating the parser pro- vides the correctness guarantees required by verified compilers and other high-assurance software that involves parsing. The validation process is independent of which technique was used to construct A. The validator is implemented and proved correct using the Coq proof assistant. As an application, we build a formally-verified parser for the C99 language. 1 Introduction Parsing remains an essential component of compilers and other programs that input textual representations of structured data. Its theoretical foundations are well understood today, and mature technology, ranging from parser combinator libraries to sophisticated parser generators, is readily available to help imple- menting parsers. The issue we focus on in this paper is that of parser correctness: how to obtain formal evidence that a parser is correct with respect to its specification? Here, following established practice, we choose to specify parsers via context-free grammars enriched with semantic actions. One application area where the parser correctness issue naturally arises is formally-verified compilers such as the CompCert verified C compiler [14]. In- deed, in the current state of CompCert, the passes that have been formally ver- ified start at abstract syntax trees (AST) for the CompCert C subset of C and extend to ASTs for three assembly languages. -

CLR(1) and LALR(1) Parsers

CLR(1) and LALR(1) Parsers C.Naga Raju B.Tech(CSE),M.Tech(CSE),PhD(CSE),MIEEE,MCSI,MISTE Professor Department of CSE YSR Engineering College of YVU Proddatur 6/21/2020 Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 9949218570 Contents • Limitations of SLR(1) Parser • Introduction to CLR(1) Parser • Animated example • Limitation of CLR(1) • LALR(1) Parser Animated example • GATE Problems and Solutions Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 9949218570 Drawbacks of SLR(1) ❖ The SLR Parser discussed in the earlier class has certain flaws. ❖ 1.On single input, State may be included a Final Item and a Non- Final Item. This may result in a Shift-Reduce Conflict . ❖ 2.A State may be included Two Different Final Items. This might result in a Reduce-Reduce Conflict Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 6/21/2020 9949218570 ❖ 3.SLR(1) Parser reduces only when the next token is in Follow of the left-hand side of the production. ❖ 4.SLR(1) can reduce shift-reduce conflicts but not reduce-reduce conflicts ❖ These two conflicts are reduced by CLR(1) Parser by keeping track of lookahead information in the states of the parser. ❖ This is also called as LR(1) grammar Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 6/21/2020 9949218570 CLR(1) Parser ❖ LR(1) Parser greatly increases the strength of the parser, but also the size of its parse tables. ❖ The LR(1) techniques does not rely on FOLLOW sets, but it keeps the Specific Look-ahead with each item. Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 6/21/2020 9949218570 CLR(1) Parser ❖ LR(1) Parsing configurations have the general form: A –> X1...Xi • Xi+1...Xj , a ❖ The Look Ahead -

Parser Generation Bottom-Up Parsing LR Parsing Constructing LR Parser

CS421 COMPILERS AND INTERPRETERS CS421 COMPILERS AND INTERPRETERS Parser Generation Bottom-Up Parsing • Main Problem: given a grammar G, how to build a top-down parser or a • Construct parse tree “bottom-up” --- from leaves to the root bottom-up parser for it ? • Bottom-up parsing always constructs right-most derivation • parser : a program that, given a sentence, reconstructs a derivation for that • Important parsing algorithms: shift-reduce, LR parsing sentence ---- if done sucessfully, it “recognize” the sentence • LR parser components: input, stack (strings of grammar symbols and states), • all parsers read their input left-to-right, but construct parse tree differently. driver routine, parsing tables. • bottom-up parsers --- construct the tree from leaves to root input: a1 a2 a3 a4 ...... an $ shift-reduce, LR, SLR, LALR, operator precedence stack s m LR Parsing output • top-down parsers --- construct the tree from root to leaves Xm .. recursive descent, predictive parsing, LL(1) s1 X1 s0 parsing Copyright 1994 - 2015 Zhong Shao, Yale University Parser Generation: Page 1 of 27 Copyright 1994 - 2015 Zhong Shao, Yale University Parser Generation: Page 2 of 27 CS421 COMPILERS AND INTERPRETERS CS421 COMPILERS AND INTERPRETERS LR Parsing Constructing LR Parser How to construct the parsing table and ? • A sequence of new state symbols s0,s1,s2,..., sm ----- each state ACTION GOTO sumarize the information contained in the stack below it. • basic idea: first construct DFA to recognize handles, then use DFA to construct the parsing tables ! different parsing table yield different LR parsers SLR(1), • Parsing configurations: (stack, remaining input) written as LR(1), or LALR(1) (s0X1s1X2s2...Xmsm , aiai+1ai+2...an$) • augmented grammar for context-free grammar G = G(T,N,P,S) is defined as G’ next “move” is determined by sm and ai = G’(T, N { S’}, P { S’ -> S}, S’) ------ adding non-terminal S’ and the • Parsing tables: ACTION[s,a] and GOTO[s,X] production S’ -> S, and S’ is the new start symbol. -

Elkhound: a Fast, Practical GLR Parser Generator

Published in Proc. of Conference on Compiler Construction, 2004, pp. 73–88. Elkhound: A Fast, Practical GLR Parser Generator Scott McPeak and George C. Necula ? University of California, Berkeley {smcpeak,necula}@cs.berkeley.edu Abstract. The Generalized LR (GLR) parsing algorithm is attractive for use in parsing programming languages because it is asymptotically efficient for typical grammars, and can parse with any context-free gram- mar, including ambiguous grammars. However, adoption of GLR has been slowed by high constant-factor overheads and the lack of a general, user-defined action interface. In this paper we present algorithmic and implementation enhancements to GLR to solve these problems. First, we present a hybrid algorithm that chooses between GLR and ordinary LR on a token-by-token ba- sis, thus achieving competitive performance for determinstic input frag- ments. Second, we describe a design for an action interface and a new worklist algorithm that can guarantee bottom-up execution of actions for acyclic grammars. These ideas are implemented in the Elkhound GLR parser generator. To demonstrate the effectiveness of these techniques, we describe our ex- perience using Elkhound to write a parser for C++, a language notorious for being difficult to parse. Our C++ parser is small (3500 lines), efficient and maintainable, employing a range of disambiguation strategies. 1 Introduction The state of the practice in automated parsing has changed little since the intro- duction of YACC (Yet Another Compiler-Compiler), an LALR(1) parser genera- tor, in 1975 [1]. An LALR(1) parser is deterministic: at every point in the input, it must be able to decide which grammar rule to use, if any, utilizing only one token of lookahead [2]. -

LR Parsing, LALR Parser Generators Lecture 10 Outline • Review Of

Outline • Review of bottom-up parsing LR Parsing, LALR Parser Generators • Computing the parsing DFA • Using parser generators Lecture 10 Prof. Fateman CS 164 Lecture 10 1 Prof. Fateman CS 164 Lecture 10 2 Bottom-up Parsing (Review) The Shift and Reduce Actions (Review) • A bottom-up parser rewrites the input string • Recall the CFG: E → int | E + (E) to the start symbol • A bottom-up parser uses two kinds of actions: • The state of the parser is described as •Shiftpushes a terminal from input on the stack α I γ – α is a stack of terminals and non-terminals E + (I int ) ⇒ E + (int I ) – γ is the string of terminals not yet examined •Reducepops 0 or more symbols off the stack (the rule’s rhs) and pushes a non-terminal on • Initially: I x1x2 . xn the stack (the rule’s lhs) E + (E + ( E ) I ) ⇒ E +(E I ) Prof. Fateman CS 164 Lecture 10 3 Prof. Fateman CS 164 Lecture 10 4 LR(1) Parsing. An Example Key Issue: When to Shift or Reduce? int int + (int) + (int)$ shift 0 1 I int + (int) + (int)$ E → int • Idea: use a finite automaton (DFA) to decide E E → int I ( on $, + E I + (int) + (int)$ shift(x3) when to shift or reduce 2 + 3 4 E + (int I ) + (int)$ E → int – The input is the stack accept E int E + (E ) + (int)$ shift – The language consists of terminals and non-terminals on $ I ) E → int E + (E) I + (int)$ E → E+(E) 7 6 5 on ), + E I + (int)$ shift (x3) • We run the DFA on the stack and we examine E → E + (E) + E + (int )$ E → int the resulting state X and the token tok after I on $, + int I E + (E )$ shift –If X has a transition labeled tok then shift ( I 8 9 β E + (E) I $ E → E+(E) –If X is labeled with “A → on tok”then reduce E + E I $ accept 10 11 E → E + (E) Prof. -

Unit-5 Parsers

UNIT-5 PARSERS LR Parsers: • The most powerful shift-reduce parsing (yet efficient) is: • LR parsing is attractive because: – LR parsing is most general non-backtracking shift-reduce parsing, yet it is still efficient. – The class of grammars that can be parsed using LR methods is a proper superset of the class of grammars that can be parsed with predictive parsers. LL(1)-Grammars ⊂ LR(1)-Grammars – An LR-parser can detect a syntactic error as soon as it is possible to do so a left-to-right scan of the input. – covers wide range of grammars. • SLR – simple LR parser • LR – most general LR parser • LALR – intermediate LR parser (look-head LR parser) • SLR, LR and LALR work same (they used the same algorithm), only their parsing tables are different. LR Parsing Algorithm: A Configuration of LR Parsing Algorithm: A configuration of a LR parsing is: • Sm and ai decides the parser action by consulting the parsing action table. (Initial Stack contains just So ) • A configuration of a LR parsing represents the right sentential form: X1 ... Xm ai ai+1 ... an $ Actions of A LR-Parser: 1. shift s -- shifts the next input symbol and the state s onto the stack ( So X1 S1 ... Xm Sm, ai ai+1 ... an $ ) è ( So X1 S1 ..Xm Sm ai s, ai+1 ...an $ ) 2. reduce Aβ→ (or rn where n is a production number) – pop 2|β| (=r) items from the stack; – then push A and s where s=goto[sm-r,A] ( So X1 S1 ... Xm Sm, ai ai+1 .. -

Bottom-Up Parsing Swarnendu Biswas

CS 335: Bottom-up Parsing Swarnendu Biswas Semester 2019-2020-II CSE, IIT Kanpur Content influenced by many excellent references, see References slide for acknowledgements. Rightmost Derivation of 푎푏푏푐푑푒 푆 → 푎퐴퐵푒 Input string: 푎푏푏푐푑푒 퐴 → 퐴푏푐 | 푏 푆 → 푎퐴퐵푒 퐵 → 푑 → 푎퐴푑푒 → 푎퐴푏푐푑푒 → 푎푏푏푐푑푒 푆 푟푚 푆 푟푚 푆 푟푚 푆 푟푚 푆 푎 퐴 퐵 푒 푎 퐴 퐵 푒 푎 퐴 퐵 푒 푎 퐴 퐵 푒 푑 퐴 푏 푐 푑 퐴 푏 푐 푑 푏 CS 335 Swarnendu Biswas Bottom-up Parsing Constructs the parse tree starting from the leaves and working up toward the root 푆 → 푎퐴퐵푒 Input string: 푎푏푏푐푑푒 퐴 → 퐴푏푐 | 푏 푆 → 푎퐴퐵푒 푎푏푏푐푑푒 퐵 → 푑 → 푎퐴푑푒 → 푎퐴푏푐푑푒 → 푎퐴푏푐푑푒 → 푎퐴푑푒 → 푎푏푏푐푑푒 → 푎퐴퐵푒 → 푆 reverse of rightmost CS 335 Swarnendu Biswas derivation Bottom-up Parsing 푆 → 푎퐴퐵푒 Input string: 푎푏푏푐푑푒 퐴 → 퐴푏푐 | 푏 푎푏푏푐푑푒 퐵 → 푑 → 푎퐴푏푐푑푒 → 푎퐴푑푒 → 푎퐴퐵푒 → 푆 푎푏푏푐푑푒⇒ 푎 퐴 푏 푐 푑 푒 ⇒ 푎 퐴 푑 푒 ⇒ 푎 퐴 퐵 푒 ⇒ 푆 푏 퐴 푏 푐 퐴 푏 푐 푑 푎 퐴 퐵 푒 푏 푏 퐴 푏 푐 푑 푏 CS 335 Swarnendu Biswas Reduction • Bottom-up parsing reduces a string 푤 to the start symbol 푆 • At each reduction step, a chosen substring that is the rhs (or body) of a production is replaced by the lhs (or head) nonterminal Derivation 푆 훾0 훾1 훾2 … 훾푛−1 훾푛 = 푤 푟푚 푟푚 푟푚 푟푚 푟푚 푟푚 Bottom-up Parser CS 335 Swarnendu Biswas Handle • Handle is a substring that matches the body of a production • Reducing the handle is one step in the reverse of the rightmost derivation Right Sentential Form Handle Reducing Production 퐸 → 퐸 + 푇 | 푇 ∗ 퐹 → 푇 → 푇 ∗ 퐹 | 퐹 id1 id2 id1 id 퐹 → 퐸 | id 퐹 ∗ id2 퐹 푇 → 퐹 푇 ∗ id2 id2 퐹 → id 푇 ∗ 퐹 푇 ∗ 퐹 푇 → 푇 ∗ 퐹 푇 푇 퐸 → 푇 CS 335 Swarnendu Biswas Handle Although 푇 is the body of the production 퐸 → 푇, -

Compiler Construction

Compiler construction PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 10 Dec 2011 02:23:02 UTC Contents Articles Introduction 1 Compiler construction 1 Compiler 2 Interpreter 10 History of compiler writing 14 Lexical analysis 22 Lexical analysis 22 Regular expression 26 Regular expression examples 37 Finite-state machine 41 Preprocessor 51 Syntactic analysis 54 Parsing 54 Lookahead 58 Symbol table 61 Abstract syntax 63 Abstract syntax tree 64 Context-free grammar 65 Terminal and nonterminal symbols 77 Left recursion 79 Backus–Naur Form 83 Extended Backus–Naur Form 86 TBNF 91 Top-down parsing 91 Recursive descent parser 93 Tail recursive parser 98 Parsing expression grammar 100 LL parser 106 LR parser 114 Parsing table 123 Simple LR parser 125 Canonical LR parser 127 GLR parser 129 LALR parser 130 Recursive ascent parser 133 Parser combinator 140 Bottom-up parsing 143 Chomsky normal form 148 CYK algorithm 150 Simple precedence grammar 153 Simple precedence parser 154 Operator-precedence grammar 156 Operator-precedence parser 159 Shunting-yard algorithm 163 Chart parser 173 Earley parser 174 The lexer hack 178 Scannerless parsing 180 Semantic analysis 182 Attribute grammar 182 L-attributed grammar 184 LR-attributed grammar 185 S-attributed grammar 185 ECLR-attributed grammar 186 Intermediate language 186 Control flow graph 188 Basic block 190 Call graph 192 Data-flow analysis 195 Use-define chain 201 Live variable analysis 204 Reaching definition 206 Three address -

Practical Dynamic Grammars for Dynamic Languages Lukas Renggli, St´Ephane Ducasse, Tudor Gˆırba,Oscar Nierstrasz

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by HAL - Lille 3 Practical Dynamic Grammars for Dynamic Languages Lukas Renggli, St´ephane Ducasse, Tudor G^ırba,Oscar Nierstrasz To cite this version: Lukas Renggli, St´ephaneDucasse, Tudor G^ırba,Oscar Nierstrasz. Practical Dynamic Gram- mars for Dynamic Languages. 4th Workshop on Dynamic Languages and Applications (DYLA 2010), 2010, Malaga, Spain. 2010. <hal-00746253> HAL Id: hal-00746253 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-00746253 Submitted on 28 Oct 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. ∗ Practical Dynamic Grammars for Dynamic Languages Lukas Renggli Stéphane Ducasse Software Composition Group, RMoD, INRIA-Lille Nord University of Bern, Switzerland Europe, France scg.unibe.ch rmod.lille.inria.fr Tudor Gîrba Oscar Nierstrasz Sw-eng. Software Engineering Software Composition Group, GmbH, Switzerland University of Bern, Switzerland www.sw-eng.ch scg.unibe.ch ABSTRACT tion 2 introduces the PetitParser framework. Section 3 dis- Grammars for programming languages are traditionally spec- cusses important aspects of a dynamic approach, such as ified statically. They are hard to compose and reuse due composition, correctness, performance and tool support. -

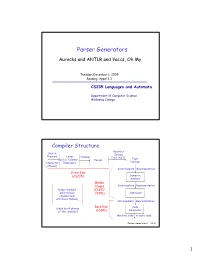

Parser Generators

Parser Generators Aurochs and ANTLR and Yaccs,,y Oh My Tuesday, December 1, 2009 Reading: Appel 3.3 CS235 Languages and Automata Department of Computer Science Wellesley College Compiler Structure Abstract Source Syntax Program Lexer Tokens Tree (AST) Type (a.k.a. Scanner, Parser (character Tokenizer) Checker stream) Intermediate Representation Front End (CS235) Semantic Analysis Middle Stages Intermediate Representation Global Analysis (CS251/ Information CS301) Optimizer (Symbol and Attribute Tables) Intermediate Representation Back End Code (used by all phases Generator of the compiler) (CS301) Machine code or byte code Parser Generators 34-2 1 Motivation We now know how to construct LL(k) and LR(k) parsers by hand. But constructing parser tables from grammars and implementing parsers from parser tables is tedious and error prone. Isn’t there a better way? Idea: Hey, aren’t computers good at automating these sorts of things? Parser Generators 34-3 Parser Generators A parser generator is a program whose inputs are: 1. a grammar that specifies a tree structure for linear sequences of tokens (typically created by a separate lexer program). 2. a specification of semantic actions to perform when building the parse tree. Its output is an automatically constructed program that parses a token sequence into a tree, performing the specified semantic actions along the way In the remainder of this lecture, we will explore and compare a two parser generators: Yacc and Aurochs. Parser Generators 34-4 2 ml-yacc: An LALR(1) Parser Generator Slip.yacc -

LNCS 9031, Pp

Faster, Practical GLL Parsing Ali Afroozeh and Anastasia Izmaylova Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica, 1098 XG Amsterdam, The Netherlands {ali.afroozeh, anastasia.izmaylova}@cwi.nl Abstract. Generalized LL (GLL) parsing is an extension of recursive- descent (RD) parsing that supports all context-free grammars in cubic time and space. GLL parsers have the direct relationship with the gram- mar that RD parsers have, and therefore, compared to GLR, are easier to understand, debug, and extend. This makes GLL parsing attractive for parsing programming languages. In this paper we propose a more efficient Graph-Structured Stack (GSS) for GLL parsing that leads to significant performance improve- ment. We also discuss a number of optimizations that further improve the performance of GLL. Finally, for practical scannerless parsing of pro- gramming languages, we show how common lexical disambiguation filters canbeintegratedinGLLparsing. Our new formulation of GLL parsing is implemented as part of the Iguana parsing framework. We evaluate the effectiveness of our approach using a highly-ambiguous grammar and grammars of real programming languages. Our results, compared to the original GLL, show a speedup factor of 10 on the highly-ambiguous grammar, and a speedup factor of 1.5, 1.7, and 5.2 on the grammars of Java, C#, and OCaml, respectively. 1 Introduction Developing efficient parsers for programming languages is a difficult task that is usually automated by a parser generator. Since Knuth’s seminal paper [1] on LR parsing, and DeRemer’s work on practical LR parsing (LALR) [2], parsers of many major programming languages have been constructed using LALR parser generators such as Yacc [3]. -

Principled Procedural Parsing Nicolas Laurent

Principled Procedural Parsing Nicolas Laurent August 2019 Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Applied Science in Engineering Institute of Information and Communication Technologies, Electronics and Applied Mathematics (ICTEAM) Louvain School of Engineering (EPL) Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain) Louvain-la-Neuve Belgium Thesis Committee Prof. Kim Mens, Advisor UCLouvain/ICTEAM, Belgium Prof. Charles Pecheur, Chair UCLouvain/ICTEAM, Belgium Prof. Peter Van Roy UCLouvain/ICTEAM Belgium Prof. Anya Helene Bagge UIB/II, Norway Prof. Tijs van der Storm CWI/SWAT & UG, The Netherlands Contents Contents3 1 Introduction7 1.1 Parsing............................7 1.2 Inadequacy: Flexibility Versus Simplicity.........8 1.3 The Best of Both Worlds.................. 10 1.4 The Approach: Principled Procedural Parsing....... 13 1.5 Autumn: Architecture of a Solution............ 15 1.6 Overview & Contributions.................. 17 2 Background 23 2.1 Context Free Grammars (CFGs).............. 23 2.1.1 The CFG Formalism................. 23 2.1.2 CFG Parsing Algorithms.............. 25 2.1.3 Top-Down Parsers.................. 26 2.1.4 Bottom-Up Parsers.................. 30 2.1.5 Chart Parsers..................... 33 2.2 Top-Down Recursive-Descent Ad-Hoc Parsers....... 35 2.3 Parser Combinators..................... 36 2.4 Parsing Expression Grammars (PEGs)........... 39 2.4.1 Expressions, Ordered Choice and Lookahead... 39 2.4.2 PEGs and Recursive-Descent Parsers........ 42 2.4.3 The Single Parse Rule, Greed and (Lack of) Ambi- guity.......................... 43 2.4.4 The PEG Algorithm................. 44 2.4.5 Packrat Parsing.................... 45 2.5 Expression Parsing...................... 47 2.6 Error Reporting........................ 50 2.6.1 Overview....................... 51 2.6.2 The Furthest Error Heuristic...........