Unit-5 Parsers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parser Tables for Non-LR(1) Grammars with Conflict Resolution Joel E

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Science of Computer Programming 75 (2010) 943–979 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of Computer Programming journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scico The IELR(1) algorithm for generating minimal LR(1) parser tables for non-LR(1) grammars with conflict resolution Joel E. Denny ∗, Brian A. Malloy School of Computing, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634, USA article info a b s t r a c t Article history: There has been a recent effort in the literature to reconsider grammar-dependent software Received 17 July 2008 development from an engineering point of view. As part of that effort, we examine a Received in revised form 31 March 2009 deficiency in the state of the art of practical LR parser table generation. Specifically, LALR Accepted 12 August 2009 sometimes generates parser tables that do not accept the full language that the grammar Available online 10 September 2009 developer expects, but canonical LR is too inefficient to be practical particularly during grammar development. In response, many researchers have attempted to develop minimal Keywords: LR parser table generation algorithms. In this paper, we demonstrate that a well known Grammarware Canonical LR algorithm described by David Pager and implemented in Menhir, the most robust minimal LALR LR(1) implementation we have discovered, does not always achieve the full power of Minimal LR canonical LR(1) when the given grammar is non-LR(1) coupled with a specification for Yacc resolving conflicts. We also detail an original minimal LR(1) algorithm, IELR(1) (Inadequacy Bison Elimination LR(1)), which we have implemented as an extension of GNU Bison and which does not exhibit this deficiency. -

Chapter 4 Syntax Analysis

Chapter 4 Syntax Analysis By Varun Arora Outline Role of parser Context free grammars Top down parsing Bottom up parsing Parser generators By Varun Arora The role of parser token Source Lexical Parse tree Rest of Intermediate Parser program Analyzer Front End representation getNext Token Symbol table By Varun Arora Uses of grammars E -> E + T | T T -> T * F | F F -> (E) | id E -> TE’ E’ -> +TE’ | Ɛ T -> FT’ T’ -> *FT’ | Ɛ F -> (E) | id By Varun Arora Error handling Common programming errors Lexical errors Syntactic errors Semantic errors Lexical errors Error handler goals Report the presence of errors clearly and accurately Recover from each error quickly enough to detect subsequent errors Add minimal overhead to the processing of correct progrms By Varun Arora Error-recover strategies Panic mode recovery Discard input symbol one at a time until one of designated set of synchronization tokens is found Phrase level recovery Replacing a prefix of remaining input by some string that allows the parser to continue Error productions Augment the grammar with productions that generate the erroneous constructs Global correction Choosing minimal sequence of changes to obtain a globally least-cost correction By Varun Arora Context free grammars Terminals Nonterminals expression -> expression + term Start symbol expression -> expression – term productions expression -> term term -> term * factor term -> term / factor term -> factor factor -> (expression) factor -> id By Varun Arora Derivations Productions are treated as -

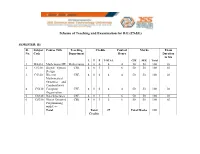

Scheme of Teaching and Examination for BE

Scheme of Teaching and Examination for B.E (CS&E) SEMESTER: III Sl. Subject Course Title Teaching Credits Contact Marks Exam No. Code Department Hours Duration in hrs L T P TOTAL CIE SEE Total 1 MA310 Mathematics III Mathematics 4 0 0 4 4 50 50 100 03 2 CS310 Digital System CSE 4 0 1 5 6 50 50 100 03 Design 3 CS320 Discrete CSE 4 0 0 4 4 50 50 100 03 Mathematical Structures and Combinatorics 4 CS330 Computer CSE 4 0 0 4 4 50 50 100 03 Organization 5 CS340 Data Structures CSE 4 0 1 5 6 50 50 100 03 6 CS350 Object Oriented CSE 4 0 1 5 6 50 50 100 03 Programming with C++ Total Total 27 Total Marks 600 Credits Scheme of Teaching and Examination for B.E (CS&E) SEMESTER: IV Sl. Subject Course Title Teaching Credits Contact Marks Exam No. Code Department Hours Duration in hrs L T P TOTAL CIE SEE Total 1 MA410 Probability, Mathematics 4 0 0 4 4 50 50 100 03 Statistics and Queuing 2 CS410 Operating CSE 4 0 1 5 6 50 50 100 03 Systems 3 CS420 Design and CSE 4 0 1 5 6 50 50 100 03 Analysis of Algorithms 4 CS430 Theory of CSE 4 0 0 4 4 50 50 100 03 Computation 5 CS440 Microprocessors CSE 4 0 1 5 6 50 50 100 03 6 CS450 Data CSE 4 0 0 4 4 50 50 100 03 Communication Total Total 27 Total Marks 600 Credits Scheme of Teaching and Examination for B.E (CS&E) SEMESTER: V Sl. -

Validating LR(1) Parsers

Validating LR(1) Parsers Jacques-Henri Jourdan1;2, Fran¸coisPottier2, and Xavier Leroy2 1 Ecole´ Normale Sup´erieure 2 INRIA Paris-Rocquencourt Abstract. An LR(1) parser is a finite-state automaton, equipped with a stack, which uses a combination of its current state and one lookahead symbol in order to determine which action to perform next. We present a validator which, when applied to a context-free grammar G and an automaton A, checks that A and G agree. Validating the parser pro- vides the correctness guarantees required by verified compilers and other high-assurance software that involves parsing. The validation process is independent of which technique was used to construct A. The validator is implemented and proved correct using the Coq proof assistant. As an application, we build a formally-verified parser for the C99 language. 1 Introduction Parsing remains an essential component of compilers and other programs that input textual representations of structured data. Its theoretical foundations are well understood today, and mature technology, ranging from parser combinator libraries to sophisticated parser generators, is readily available to help imple- menting parsers. The issue we focus on in this paper is that of parser correctness: how to obtain formal evidence that a parser is correct with respect to its specification? Here, following established practice, we choose to specify parsers via context-free grammars enriched with semantic actions. One application area where the parser correctness issue naturally arises is formally-verified compilers such as the CompCert verified C compiler [14]. In- deed, in the current state of CompCert, the passes that have been formally ver- ified start at abstract syntax trees (AST) for the CompCert C subset of C and extend to ASTs for three assembly languages. -

CWI Scanprofile/PDF/300

Centrum voor Wiskunde en lnformatica Centre for Mathematics and Computer Science J. Heering, P. Klint, J.G. Rekers Incremental generation of parsers , Computer Science/Department of Software Technology Report CS-R8822 May Biblk>tlleek Centrum ypor Wisl~unde en lnformatk:a Am~tel>dam The Centre for Mathematics and Computer Science is a research institute of the Stichting Mathematisch Centrum, which was founded on February 11, 1946, as a nonprofit institution aim ing at the promotion of mathematics, computer science, and their applications. It is sponsored by the Dutch Government through the Netherlands Organization for the Advancement of Pure Research (Z.W.0.). q\ ' Copyright (t:: Stichting Mathematisch Centrum, Amsterdam 1 Incremental Generation of Parsers J. Heering Department of Software Technology, Centre for Mathematics and Computer Science P.O. Box 4079, 1009 AS Amsterdam, The Netherlands P. Klint Department of Software Technology, Centre for Mathematics and Computer Science P.O. Box 4079, 1009 AS Amsterdam, The Netherlands and Programming Research Group, University of Amsterdam P.O. BOX 41882, 1009 DB Amsterdam, The Netherlands J. Rekers Department of Software Technology, Centre for Mathematics and Computer Science P.O. Box 4079, 1009 AB Amsterdam, The Netherlands A parser checks whether a text is a sentence in a language. Therefore, the parser is provided with the grammar of the language, and it usually generates a structure (parse tree) that represents the text according to that grammar. Most present-day parsers are not directly driven by the grammar but by a 'parse table', which is generated by a parse table generator. A table based parser wolks more efficiently than a grammar based parser does, and provided that the parser is used often enough, the cost of gen erating the parse table is outweighed by the gain in parsing efficiency. -

B.E Computer Science and Engineering

CURRICULUM B.E. – Computer Science and Engineering Regulations 2019 VISION MISSION “To become a center of excellence • To produce technocrats in the in Computer Science and industry and academia by Engineering and Research to create educating computer concepts and global leaders with holistic growth techniques. and ethical values for the industry • To facilitate the students to and academics.” trigger more creativity by applying modern tools and technologies in the field of computer science and engineering. • To inculcate the spirit of ethical values contributing to the welfare of the society. Department of Computer Science and Engineering Department of CSE, Francis Xavier Engineering College | Regulation 2019 2 Department of CSE, Francis Xavier Engineering College | Regulation 2019 5 B.E.-COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING (REGULATIONS 2019) CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM SUMMARY OF CREDIT DISTRIBUTION Range Of CREDITS PER SEMESTER Total S. TOTAL CREDITS CATEGORY Credits No CREDIT IN % I II III IV V VI VII VIII Min Max 1 HSS 3 2 3 8 4.5% 9 11 2 BS 12 4 4 4 24 14.5% 21 21 3 ES 8 11 3 22 13.9% 23 26 4 PC 13 17 10 11 8 59 35.75% 59 59 5 PE 6 6 6 6 24 14.5% 24 27 6 OE 3 3 3 3 12 7.3% 12 15 7 EEC 2 2 1 10 15 9.1% 12 15 TOTAL 23 18 20 23 22 22 21 16 165 100% - - BS - Basic Sciences ES - Engineering Sciences HSS - Humanities and Social Sciences PC - Professional Core PE - Professional Elective OE - Open Elective EEC - Employability Enhancement Course Department of CSE, Francis Xavier Engineering College | Regulation 2019 6 B.E.- COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING (REGULATIONS 2019) CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM I – VIII SEMESTERS CURRICULUM AND SYLLABI FIRST SEMESTER Code No. -

Compiler Design

CCOOMMPPIILLEERR DDEESSIIGGNN -- PPAARRSSEERR http://www.tutorialspoint.com/compiler_design/compiler_design_parser.htm Copyright © tutorialspoint.com In the previous chapter, we understood the basic concepts involved in parsing. In this chapter, we will learn the various types of parser construction methods available. Parsing can be defined as top-down or bottom-up based on how the parse-tree is constructed. Top-Down Parsing We have learnt in the last chapter that the top-down parsing technique parses the input, and starts constructing a parse tree from the root node gradually moving down to the leaf nodes. The types of top-down parsing are depicted below: Recursive Descent Parsing Recursive descent is a top-down parsing technique that constructs the parse tree from the top and the input is read from left to right. It uses procedures for every terminal and non-terminal entity. This parsing technique recursively parses the input to make a parse tree, which may or may not require back-tracking. But the grammar associated with it ifnotleftfactored cannot avoid back- tracking. A form of recursive-descent parsing that does not require any back-tracking is known as predictive parsing. This parsing technique is regarded recursive as it uses context-free grammar which is recursive in nature. Back-tracking Top- down parsers start from the root node startsymbol and match the input string against the production rules to replace them ifmatched. To understand this, take the following example of CFG: S → rXd | rZd X → oa | ea Z → ai For an input string: read, a top-down parser, will behave like this: It will start with S from the production rules and will match its yield to the left-most letter of the input, i.e. -

Compiler Construction

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Compiler Construction An 18-lecture course Alan Mycroft Computer Laboratory, Cambridge University http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/users/am/ Lent Term 2007 Compiler Construction 1 Lent Term 2007 Course Plan UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Part A : intro/background Part B : a simple compiler for a simple language Part C : implementing harder things Compiler Construction 2 Lent Term 2007 A compiler UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE A compiler is a program which translates the source form of a program into a semantically equivalent target form. • Traditionally this was machine code or relocatable binary form, but nowadays the target form may be a virtual machine (e.g. JVM) or indeed another language such as C. • Can appear a very hard program to write. • How can one even start? • It’s just like juggling too many balls (picking instructions while determining whether this ‘+’ is part of ‘++’ or whether its right operand is just a variable or an expression ...). Compiler Construction 3 Lent Term 2007 How to even start? UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE “When finding it hard to juggle 4 balls at once, juggle them each in turn instead ...” character -token -parse -intermediate -target stream stream tree code code syn trans cg lex A multi-pass compiler does one ‘simple’ thing at once and passes its output to the next stage. These are pretty standard stages, and indeed language and (e.g. JVM) system design has co-evolved around them. Compiler Construction 4 Lent Term 2007 Compilers can be big and hard to understand UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Compilers can be very large. In 2004 the Gnu Compiler Collection (GCC) was noted to “[consist] of about 2.1 million lines of code and has been in development for over 15 years”. -

CLR(1) and LALR(1) Parsers

CLR(1) and LALR(1) Parsers C.Naga Raju B.Tech(CSE),M.Tech(CSE),PhD(CSE),MIEEE,MCSI,MISTE Professor Department of CSE YSR Engineering College of YVU Proddatur 6/21/2020 Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 9949218570 Contents • Limitations of SLR(1) Parser • Introduction to CLR(1) Parser • Animated example • Limitation of CLR(1) • LALR(1) Parser Animated example • GATE Problems and Solutions Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 9949218570 Drawbacks of SLR(1) ❖ The SLR Parser discussed in the earlier class has certain flaws. ❖ 1.On single input, State may be included a Final Item and a Non- Final Item. This may result in a Shift-Reduce Conflict . ❖ 2.A State may be included Two Different Final Items. This might result in a Reduce-Reduce Conflict Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 6/21/2020 9949218570 ❖ 3.SLR(1) Parser reduces only when the next token is in Follow of the left-hand side of the production. ❖ 4.SLR(1) can reduce shift-reduce conflicts but not reduce-reduce conflicts ❖ These two conflicts are reduced by CLR(1) Parser by keeping track of lookahead information in the states of the parser. ❖ This is also called as LR(1) grammar Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 6/21/2020 9949218570 CLR(1) Parser ❖ LR(1) Parser greatly increases the strength of the parser, but also the size of its parse tables. ❖ The LR(1) techniques does not rely on FOLLOW sets, but it keeps the Specific Look-ahead with each item. Prof.C.NagaRaju YSREC of YVU 6/21/2020 9949218570 CLR(1) Parser ❖ LR(1) Parsing configurations have the general form: A –> X1...Xi • Xi+1...Xj , a ❖ The Look Ahead -

Parser Generation Bottom-Up Parsing LR Parsing Constructing LR Parser

CS421 COMPILERS AND INTERPRETERS CS421 COMPILERS AND INTERPRETERS Parser Generation Bottom-Up Parsing • Main Problem: given a grammar G, how to build a top-down parser or a • Construct parse tree “bottom-up” --- from leaves to the root bottom-up parser for it ? • Bottom-up parsing always constructs right-most derivation • parser : a program that, given a sentence, reconstructs a derivation for that • Important parsing algorithms: shift-reduce, LR parsing sentence ---- if done sucessfully, it “recognize” the sentence • LR parser components: input, stack (strings of grammar symbols and states), • all parsers read their input left-to-right, but construct parse tree differently. driver routine, parsing tables. • bottom-up parsers --- construct the tree from leaves to root input: a1 a2 a3 a4 ...... an $ shift-reduce, LR, SLR, LALR, operator precedence stack s m LR Parsing output • top-down parsers --- construct the tree from root to leaves Xm .. recursive descent, predictive parsing, LL(1) s1 X1 s0 parsing Copyright 1994 - 2015 Zhong Shao, Yale University Parser Generation: Page 1 of 27 Copyright 1994 - 2015 Zhong Shao, Yale University Parser Generation: Page 2 of 27 CS421 COMPILERS AND INTERPRETERS CS421 COMPILERS AND INTERPRETERS LR Parsing Constructing LR Parser How to construct the parsing table and ? • A sequence of new state symbols s0,s1,s2,..., sm ----- each state ACTION GOTO sumarize the information contained in the stack below it. • basic idea: first construct DFA to recognize handles, then use DFA to construct the parsing tables ! different parsing table yield different LR parsers SLR(1), • Parsing configurations: (stack, remaining input) written as LR(1), or LALR(1) (s0X1s1X2s2...Xmsm , aiai+1ai+2...an$) • augmented grammar for context-free grammar G = G(T,N,P,S) is defined as G’ next “move” is determined by sm and ai = G’(T, N { S’}, P { S’ -> S}, S’) ------ adding non-terminal S’ and the • Parsing tables: ACTION[s,a] and GOTO[s,X] production S’ -> S, and S’ is the new start symbol. -

Elkhound: a Fast, Practical GLR Parser Generator

Published in Proc. of Conference on Compiler Construction, 2004, pp. 73–88. Elkhound: A Fast, Practical GLR Parser Generator Scott McPeak and George C. Necula ? University of California, Berkeley {smcpeak,necula}@cs.berkeley.edu Abstract. The Generalized LR (GLR) parsing algorithm is attractive for use in parsing programming languages because it is asymptotically efficient for typical grammars, and can parse with any context-free gram- mar, including ambiguous grammars. However, adoption of GLR has been slowed by high constant-factor overheads and the lack of a general, user-defined action interface. In this paper we present algorithmic and implementation enhancements to GLR to solve these problems. First, we present a hybrid algorithm that chooses between GLR and ordinary LR on a token-by-token ba- sis, thus achieving competitive performance for determinstic input frag- ments. Second, we describe a design for an action interface and a new worklist algorithm that can guarantee bottom-up execution of actions for acyclic grammars. These ideas are implemented in the Elkhound GLR parser generator. To demonstrate the effectiveness of these techniques, we describe our ex- perience using Elkhound to write a parser for C++, a language notorious for being difficult to parse. Our C++ parser is small (3500 lines), efficient and maintainable, employing a range of disambiguation strategies. 1 Introduction The state of the practice in automated parsing has changed little since the intro- duction of YACC (Yet Another Compiler-Compiler), an LALR(1) parser genera- tor, in 1975 [1]. An LALR(1) parser is deterministic: at every point in the input, it must be able to decide which grammar rule to use, if any, utilizing only one token of lookahead [2]. -

LR Parsing, LALR Parser Generators Lecture 10 Outline • Review Of

Outline • Review of bottom-up parsing LR Parsing, LALR Parser Generators • Computing the parsing DFA • Using parser generators Lecture 10 Prof. Fateman CS 164 Lecture 10 1 Prof. Fateman CS 164 Lecture 10 2 Bottom-up Parsing (Review) The Shift and Reduce Actions (Review) • A bottom-up parser rewrites the input string • Recall the CFG: E → int | E + (E) to the start symbol • A bottom-up parser uses two kinds of actions: • The state of the parser is described as •Shiftpushes a terminal from input on the stack α I γ – α is a stack of terminals and non-terminals E + (I int ) ⇒ E + (int I ) – γ is the string of terminals not yet examined •Reducepops 0 or more symbols off the stack (the rule’s rhs) and pushes a non-terminal on • Initially: I x1x2 . xn the stack (the rule’s lhs) E + (E + ( E ) I ) ⇒ E +(E I ) Prof. Fateman CS 164 Lecture 10 3 Prof. Fateman CS 164 Lecture 10 4 LR(1) Parsing. An Example Key Issue: When to Shift or Reduce? int int + (int) + (int)$ shift 0 1 I int + (int) + (int)$ E → int • Idea: use a finite automaton (DFA) to decide E E → int I ( on $, + E I + (int) + (int)$ shift(x3) when to shift or reduce 2 + 3 4 E + (int I ) + (int)$ E → int – The input is the stack accept E int E + (E ) + (int)$ shift – The language consists of terminals and non-terminals on $ I ) E → int E + (E) I + (int)$ E → E+(E) 7 6 5 on ), + E I + (int)$ shift (x3) • We run the DFA on the stack and we examine E → E + (E) + E + (int )$ E → int the resulting state X and the token tok after I on $, + int I E + (E )$ shift –If X has a transition labeled tok then shift ( I 8 9 β E + (E) I $ E → E+(E) –If X is labeled with “A → on tok”then reduce E + E I $ accept 10 11 E → E + (E) Prof.