Restructuring Extractive Economies in the Caspian Basin TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECONOMY of AZERBAIJAN 25 Years of Independence

ECONOMY OF AZERBAIJAN 25 Years of Independence Prof. Dr. Osman Nuri Aras Fatih University, Istanbul, Turkey Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elchin Suleymanov Qafqaz University, Baku, Azerbaijan Assoc. Prof. Dr. Karim Mammadov Western University, Baku, Azerbaijan DESIGN Sahib Kazimov PRINTING AND BINDERING “Sharg-Garb” Publishing House A§iq aiesgar kiig., No: 17, Xatai rayonu, Baki, Azarbaycan; Tel: (+99412) 374 83 43 ISBN: 978-9952*468-57-1 © Prof. Dr. Osman Nuri Aras. Baki, 2016 © Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elchin Suleymanov. Baki. 2016 © Assoc. Prof. Dr. Karim Mammadov. Baki. 2016 Foreword During every work, whether it is academic or professional, we interact, get assistance and are guided by certain group of people who value and assist us to achieve our targets. We are sure that the people who support us and provide valuable contribution to the English version of this book will not be limited in a short list, but we would like to mention, and in certain ways, express our acknowledgement to the people who enabled us to get on a track and deliver the book in a few months. Thanks to Turan Agayeva, Ulker Gurbaneliyeva, Khayala Mahmudiu and especially to Tural Hasanov for their help in preparing and delivering this book to your valuable consideration. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT AZERBAIJAN The Establishment of the Republic of Azerbaijan 28 May 1918 The independence Day 18 October 1991 Joining to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe 30 January 1992 Joining to the United Nations 2 March 1992 Joining to the Commonweaith of independent States 19 September 1995 Joining to the Council of Europe 17 January2001 Area (thousand km^) 86.6 Population, (thousand person) (According to the beginning of 2015) 9593.0 Density of population in Ikm^(person) 111 Capital Baku Official Language Azerbaijan Currency Manat The course of Manat to Dollar (07.02.2016) 0.6389 The Head of State President ___ ________________________ ____ ______ ' .L-L; r - j = r . -

Doing Business in Azerbaijan

Doing Business in Azerbaijan 2019 Tax and Legal kpmg.az Doing Business in Azerbaijan 2019 Tax and Legal www.kpmg.az 4 Doing Business in Azerbaijan 2019 Contents Contents 4 Foreign investment 21 Foreign investment 21 About KPMG 7 Investment promotion certificates 22 Introduction to Azerbaijan 9 Safeguards for foreign investors 22 Investment climate 9 Bilateral investment treaties 23 Living and working in Azerbaijan – useful tips 10 Licensing requirements 25 Starting a business 13 Land ownership and Overview of commercial legal entities 13 other related rights 29 Types of legal entities 13 Documents confirming rights over land 29 Representative offices and branches 13 Technology parks 31 Joint-stock company (“JSC”) 14 Foreign trade 31 - Open joint-stock companies 14 - Closed joint-stock companies 14 Banking 33 An Azerbaijani subsidiary 15 Secured transactions 35 Limited liability companies (“LLC”) 15 Litigation and arbitration 37 Additional liability companies (“ALC”) 15 Strategic road maps 41 Partnerships 15 State digital payments Cooperatives 15 expansion programme 43 - Membership of a cooperative 16 Special economic zones 45 Registration 16 Alat Free Economic Zone 46 - LLC 16 - JSC 16 Intellectual property 49 - Branches or representative offices 16 Introduction 49 De-registration of companies 17 - Stage 1 17 Legislation 49 - Stage 2 18 Trademarks 50 Registration of changes 19 Patent protection of inventions, industrial designs, and utility models 50 Copyright 51 © 2019 KPMG Azerbaijan Limited. All rights reserved. Doing Business in Azerbaijan -

Nagorno-Karabakh's

Nagorno-Karabakh’s Gathering War Clouds Europe Report N°244 | 1 June 2017 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Ongoing Risks of War ....................................................................................................... 2 A. Military Tactics .......................................................................................................... 4 B. Potential Humanitarian Implications ....................................................................... 6 III. Shifts in Public Moods and Policies ................................................................................. 8 A. Azerbaijan’s Society ................................................................................................... 8 1. Popular pressure on the government ................................................................... 8 2. A tougher stance ................................................................................................... 10 B. Armenia’s Society ....................................................................................................... 12 1. Public mobilisation and anger -

The Sociolinguistic Situation of the Khinalug in Azerbaijan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Khazar University Institutional Repository The Sociolinguistic Situation of the Khinalug in Azerbaijan John M. Clifton, Laura Lucht, Gabriela Deckinga, Janfer Mak, and Calvin Tiessen SIL International 2005 2 Contents Abstract 1. Background 2. Methodology 3. Results 3.1 Khinalug Locations 3.1.1 Village inventory 3.1.2 Population and ethnic mix 3.2 Cultural Factors 3.2.1 Economic activity 3.2.2 Marriage patterns 3.2.3 Education 3.2.4 Religious activity 3.2.5 Medical facilities 3.3 Domains of Language Use 3.3.1 Physical and functional domains 3.3.2 Economic activity 3.3.3 Marriage patterns 3.3.4 Education 3.3.5 Medical facilities 3.4 Language Proficiency 3.4.1 Khinalug language proficiency 3.4.2 Azerbaijani language proficiency 3.4.3 Russian language proficiency 3.4.4 Summary profile of language proficiency 3.5 Language Attitudes 4. Discussion 4.1 Khinalug and Azerbaijani within Xınalıq Village 4.2 Khinalug and Azerbaijani outside Xınalıq Village 4.3 Russian within Xınalıq Village 5. Conclusion Appendix: Comprehensive Tables Bibliography 3 Abstract This paper presents the results of sociolinguistic research conducted in August 2000 among the Khinalug people in northeastern Azerbaijan, the majority of whom live in the villages of Xınalıq and Gülüstan. The goals of the research were to investigate patterns of language use, bilingualism, and language attitudes with regard to the Khinalug, Azerbaijani, and Russian languages in the Khinalug community. Of particular interest is the stable diglossia that has developed between Khinalug and Azerbaijani. -

THE BENEFITS of ETHNIC WAR Understanding Eurasia's

v53.i4.524.king 9/27/01 5:18 PM Page 524 THE BENEFITS OF ETHNIC WAR Understanding Eurasia’s Unrecognized States By CHARLES KING* AR is the engine of state building, but it is also good for busi- Wness. Historically, the three have often amounted to the same thing. The consolidation of national states in western Europe was in part a function of the interests of royal leaders in securing sufficient rev- enue for war making. In turn, costly military engagements were highly profitable enterprises for the suppliers of men, ships, and weaponry. The great affairs of statecraft, says Shakespeare’s Richard II as he seizes his uncle’s fortune to finance a war, “do ask some charge.” The distinc- tion between freebooter and founding father, privateer and president, has often been far murkier in fact than national mythmaking normally allows. Only recently, however, have these insights figured in discussions of contemporary ethnic conflict and civil war. Focused studies of the me- chanics of warfare, particularly in cases such as Sudan, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, have highlighted the complex economic incentives that can push violence forward, as well as the ways in which the easy labels that analysts use to identify such conflicts—as “ethnic” or “religious,” say—always cloud more than they clarify.1 Yet how precisely does the chaos of war become transformed into networks of profit, and how in turn can these informal networks harden into the institutions of states? Post-Soviet Eurasia provides an enlightening instance of these processes in train. In the 1990s a half dozen small wars raged across the region, a series of armed conflicts that future historians might term collectively the * The author would like to thank three anonymous referees for comments on an earlier draft of this article and Lori Khatchadourian, Nelson Kasfir, Christianne Hardy Wohlforth, Chester Crocker, and Michael Brown for helpful conversations. -

PCT Fee Tables

PCT Fee Tables (amounts on 23 December 2020, unless otherwise indicated) The following Tables show the amounts and currencies of the main PCT fees which are payable to the receiving Offices (ROs) and the International Preliminary Examining Authorities (IPEAs) during the international phase under Chapter I (Tables I(a) and I(b)) and under Chapter II (Table II). Fees which are payable only in particular circumstances are not shown; nor are details of certain reductions and refunds which may be available; such information can be found in the PCT Applicant’s Guide, Annexes C, D and E. Note that all amounts are subject to change due to variations in the fees themselves or fluctuations in exchange rates. The international filing fee may be reduced by CHF 100, 200 or 300 where the international application, or part of the international application, is filed in electronic form, as prescribed under Item 4(a), (b) and (c) of the Schedule of Fees (annexed to the Regulations under the PCT) and the PCT Applicant’s Guide, paragraph 5.189. A 90% reduction in the international filing fee (including the fee per sheet over 30), the supplementary search handling fee and the handling fee, as well as an exemption from the transmittal fee payable to the International Bureau as receiving Office, is also available to applicants from certain States—see footnotes 2 and 13. (Note that if the CHF 100, 200 or 300 reduction, as the case may be, and the 90% reduction are applicable, the 90% reduction is calculated after the CHF 100, 200 or 300 reduction.) The footnotes to the Fee Tables follow Table II. -

Laurence Broers

PROSPECTS FOR PEACE IN NAGORNO-KARABAKH: INTERNATIONAL AND DOMESTIC PERSPECTIVES Yerevan • 2018 UDC 32.001 PROSPECTS FOR PEACE IN NAGORNO-KARABAKH: INTERNATIONAL AND DOMESTIC PERSPECTIVES. – Ed. Alexander Iskandaryan. – Yerevan: Caucasus Institute. 2018. – 156 p. This volume is based on presentations made at an international conference on Pros- pects for Peace in Nagorno-Karabakh: International and Domestic Perspectives held in Yerevan on March 15-16, 2018 in the framework of a project on Engaging society and decision-makers in dialogue for peace over the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict implement- ed by the Caucasus Institute with support from the UK Government’s Conflict, Stabil- ity and Security Fund. The project is aimed at reducing internal vulnerabilities created by unresolved conflicts and interethnic tension, and increasing the space for construc- tive dialogue on conflict resolution, creating capacities and incentives for stakeholders in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh for resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, reconciliation and peace-building. The conference brought together leading UK and Armenian experts on the conflict to discuss the current situation in the conflict, pros- pects for peace and the steps needed to achieve it. Copy editing and translations by Liana Avetisyan, Nina Iskandaryan, Armine Sahakyan, Lily Woodall Cover photo by Vachagan Gratian • www.qualia.am Cover design by Matit • www.matit.am Layout by Collage • www.collage.am The publication of this volume was made possible by the support of the UK Government’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund ISBN 978-9939-1-0739-4 © Caucasus Institute, 2018 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily rep- resent opinions of the UK Government, the Caucasus Institute or other organizations, in- cluding ones with which the authors are affiliated. -

Administrative Territorial Divisions in Different Historical Periods

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y TERRITORIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS C O N T E N T I. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 3 II. BAKU ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. General background of Baku ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. History of the city of Baku ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Museums ........................................................................................................................................................... 16 4. Historical Monuments ...................................................................................................................................... 20 The Maiden Tower ............................................................................................................................................ 20 The Shirvanshahs’ Palace ensemble ................................................................................................................ 22 The Sabael Castle ............................................................................................................................................. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

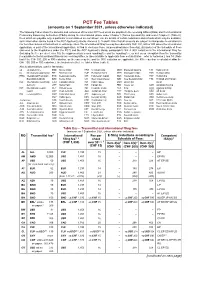

PCT Fee Tables I(B)

PCT Fee Tables (amounts on 1 September 2021, unless otherwise indicated) The following Tables show the amounts and currencies of the main PCT fees which are payable to the receiving Offices (ROs) and the International Preliminary Examining Authorities (IPEAs) during the international phase under Chapter I (Tables I(a) and I(b)) and under Chapter II (Table II). Fees which are payable only in particular circumstances are not shown; nor are details of certain reductions and refunds which may be available; such information can be found in the PCT Applicant’s Guide, Annexes C, D and E. Note that all amounts are subject to change due to variations in the fees themselves or fluctuations in exchange rates. The international filing fee may be reduced by CHF 100, 200 or 300 where the international application, or part of the international application, is filed in electronic form, as prescribed under Item 4(a), (b) and (c) of the Schedule of Fees (annexed to the Regulations under the PCT) and the PCT Applicant’s Guide, paragraph 5.189. A 90% reduction in the international filing fee (including the fee per sheet over 30), the supplementary search handling fee and the handling fee, as well as an exemption from the transmittal fee payable to the International Bureau as receiving Office, is also available to applicants from certain States—refer to footnotes 2 and 14. (Note that if the CHF 100, 200 or 300 reduction, as the case may be, and the 90% reduction are applicable, the 90% reduction is calculated after the CHF 100, 200 or 300 reduction.) The footnotes to the Fee Tables follow Table II. -

ANNEX a to the 1998 FX and CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED and RESTATED AS of NOVEMBER 19, 2017 I

ANNEX A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions _________________________ Amended and Restated November 19, 2017 Amended March 16, 2020 INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. TRADE ASSOCIATION FOR THE EMERGING MARKETS Copyright © 2000-2020 by INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. ISDA and EMTA consent to the use and photocopying of this document for the preparation of agreements with respect to derivative transactions and for research and educational purposes. ISDA and EMTA do not, however, consent to the reproduction of this document for purposes of sale. For any inquiries with regard to this document, please contact: INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. 10 East 53rd Street New York, NY 10022 www.isda.org EMTA, Inc. 405 Lexington Avenue, Suite 5304 New York, N.Y. 10174 www.emta.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 i ANNEX A CALCULATION OF RATES FOR CERTAIN SETTLEMENT RATE OPTIONS SECTION 4.3. Currencies 1 SECTION 4.4. Principal Financial Centers 6 SECTION 4.5. Settlement Rate Options 9 A. Emerging Currency Pair Single Rate Source Definitions 9 B. Non-Emerging Currency Pair Rate Source Definitions 21 C. General 22 SECTION 4.6. Certain Definitions Relating to Settlement Rate Options 23 SECTION 4.7. Corrections to Published and Displayed Rates 24 INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 Annex A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions ("Annex A"), originally published in 1998, restated in 2000 and amended and restated as of the date hereof, is intended for use in conjunction with the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended and updated from time to time (the "FX Definitions") in confirmations of individual transactions governed by (i) the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement and the 2002 ISDA Master Agreement published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. -

EXCHANGE RATES DATA FEED TERMS and CONDITIONS July 2013 Version

EXCHANGE RATES DATA FEED TERMS AND CONDITIONS July 2013 Version BETWEEN FXTOP company, Limited liability company with capital of 16 000 euros minimum, registered in Versailles (France) under number B 438 847 899, company headquarters 11 rue Kléber 78500 Sartrouville, France. Represented by Laurent PELÉ, general manager Hereafter called « FXTOP » First party, AND The subscriber of the service Hereafter called « The SUBSCRIBER » Second party OBJECT OF THE CONTRACT This contract defines the terms and conditions for the supply of exchange rates data from FXTOP to the subscriber NON-COMPETITION The subscriber should not resell or publish exchange rates in any other way than the ones defined in the present terms and conditions, especially those in the « Copyright » paragraph. The subscriber will inform FXTOP of any third party query to use exchange rates in a way that does not comply with the present terms and conditions. ACCESS PRIVACY Fxtop will give the subscriber a login and a password to access services and data. The subscriber will divulge to FXTOP any password leak that he knows about. Fxtop has the right to change the password, especially if it seems that it has been used for third party access. Fxtop could also limit access to a limited IP address range so that only the subscriber’s server(s) can access its services. EXCHANGE RATE DATA FEED The subscriber can choose the way they access the exchange rate data : - Using one of the ready-made formats (XML, Text with semi colon separation between fields (CSV), Structured Query Language (SQL) queries, Javascript Script, Ajax/JQuery, exchange rates graph).