Country Assistance Program Evaluation: Azerbaijan, 2011–2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECONOMY of AZERBAIJAN 25 Years of Independence

ECONOMY OF AZERBAIJAN 25 Years of Independence Prof. Dr. Osman Nuri Aras Fatih University, Istanbul, Turkey Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elchin Suleymanov Qafqaz University, Baku, Azerbaijan Assoc. Prof. Dr. Karim Mammadov Western University, Baku, Azerbaijan DESIGN Sahib Kazimov PRINTING AND BINDERING “Sharg-Garb” Publishing House A§iq aiesgar kiig., No: 17, Xatai rayonu, Baki, Azarbaycan; Tel: (+99412) 374 83 43 ISBN: 978-9952*468-57-1 © Prof. Dr. Osman Nuri Aras. Baki, 2016 © Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elchin Suleymanov. Baki. 2016 © Assoc. Prof. Dr. Karim Mammadov. Baki. 2016 Foreword During every work, whether it is academic or professional, we interact, get assistance and are guided by certain group of people who value and assist us to achieve our targets. We are sure that the people who support us and provide valuable contribution to the English version of this book will not be limited in a short list, but we would like to mention, and in certain ways, express our acknowledgement to the people who enabled us to get on a track and deliver the book in a few months. Thanks to Turan Agayeva, Ulker Gurbaneliyeva, Khayala Mahmudiu and especially to Tural Hasanov for their help in preparing and delivering this book to your valuable consideration. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT AZERBAIJAN The Establishment of the Republic of Azerbaijan 28 May 1918 The independence Day 18 October 1991 Joining to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe 30 January 1992 Joining to the United Nations 2 March 1992 Joining to the Commonweaith of independent States 19 September 1995 Joining to the Council of Europe 17 January2001 Area (thousand km^) 86.6 Population, (thousand person) (According to the beginning of 2015) 9593.0 Density of population in Ikm^(person) 111 Capital Baku Official Language Azerbaijan Currency Manat The course of Manat to Dollar (07.02.2016) 0.6389 The Head of State President ___ ________________________ ____ ______ ' .L-L; r - j = r . -

Policy Brief Series

The Migration, Environment Migration, Environment and Climate Change: and Climate Change: Policy Brief Series is produced as part of the Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Evidence for Policy (MECLEP) project funded by the European Union, implemented Policy Brief Series by IOM through a consortium with ISSN 2410-4930 Issue 4 | Vol. 2 | April 2016 six research partners. 2012 East Azerbaijan earthquakes © Mardetanha, 2012 Environmental migration and displacement in Azerbaijan: Highlighting the need for research and policies Irene Leonardelli, IOM Introduction From a geological and environmental point of view, the 362). Simultaneously, due to climate change, the country Caucasus region ‒ where the Republic of Azerbaijan is increasingly exposed to slow-onset processes, such (hereafter “Azerbaijan”) is located ‒ is a very active as water scarcity, salinization and pollution, rising and hazardous area; this is mainly reflected in the temperatures, sea-level fluctuation, droughts and soil intensity and the frequency of floods, storms, landslides, degradation. While natural disasters have displaced mudflows and earthquakes (ogli Mammadov, 2012:361, 67,865 people between 2009 and 2014 (IDMC, 2014), the YEARS This project is funded by the This project is implemented by the European Union International Organization for Migration 44_16 Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Policy Brief Series Issue 4 | Vol. 2 | April 2016 2 progressive exacerbation of environmental degradation Extreme weather events and slow-onset is thought to have significant adverse impacts on livelihoods and communities especially in certain areas processes in Azerbaijan of the country. Azerbaijan’s exposure to severe weather events and After gaining independence in 1991 as a result of the negative impacts on the population are increasing. -

Azerbaijan Azerbaijan

COUNTRY REPORT ON THE STATE OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE AZERBAIJAN AZERBAIJAN National Report on the State of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture in Azerbaijan Baku – December 2006 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the Second Report on the State of World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The Report is being made available by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as requested by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 7 INTRODUCTION 8 1. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Legal Updates

March 2020 An up-to-the-minute guide to developments in the legislation of the Republic of Azerbaijan Legal updates In this issue, we would like to bring ► Deadline for submission of tax reports and payment of taxes has to your attention a brief overview been extended of the following: The government has extended the deadline for submission of tax reports ► Deadline for submission of tax and payment of taxes. The statutory limitation for submission of the reports and payment of taxes reports on taxes and payment thereof has been postponed till 6 April has been extended 2020. ► The initial stages of the The decision to extend the deadline has been made because of the introduction of mandatory prolongation of non-working days due to the outbreak of COVID-19. Below health insurance have been are the types of tax in question: combined • Corporate income tax • Property tax of legal entities • Personal income tax (submitted by individuals) • Excise tax, value added tax, road and mining taxes, simplified tax on cash withdrawals, income tax on winnings (prizes) for February 2020 • Simplified withholding tax return for persons providing immovable property for February 2020 Furthermore, deadline for payment of income tax calculated by private notaries for February and the withholding tax for February in connection with employment to the state budget will be 6 April 2020. For your reference, please see the respective link: https://www.taxes.gov.az/az/post/1009 ► The initial stages of the introduction of mandatory health insurance have been combined The Cabinet of Ministers has also introduced changes to the Decree on "Sequence of implementation of compulsory health insurance in the regions of the country". -

World Bank Document

75967 Review of World Bank engagement in the Public Disclosure Authorized Irrigation and Drainage Sector in Azerbaijan Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized February 2013 Public Disclosure Authorized © 2012 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000I Internet: www.worldbank.org This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

Doing Business in Azerbaijan

Doing Business in Azerbaijan 2019 Tax and Legal kpmg.az Doing Business in Azerbaijan 2019 Tax and Legal www.kpmg.az 4 Doing Business in Azerbaijan 2019 Contents Contents 4 Foreign investment 21 Foreign investment 21 About KPMG 7 Investment promotion certificates 22 Introduction to Azerbaijan 9 Safeguards for foreign investors 22 Investment climate 9 Bilateral investment treaties 23 Living and working in Azerbaijan – useful tips 10 Licensing requirements 25 Starting a business 13 Land ownership and Overview of commercial legal entities 13 other related rights 29 Types of legal entities 13 Documents confirming rights over land 29 Representative offices and branches 13 Technology parks 31 Joint-stock company (“JSC”) 14 Foreign trade 31 - Open joint-stock companies 14 - Closed joint-stock companies 14 Banking 33 An Azerbaijani subsidiary 15 Secured transactions 35 Limited liability companies (“LLC”) 15 Litigation and arbitration 37 Additional liability companies (“ALC”) 15 Strategic road maps 41 Partnerships 15 State digital payments Cooperatives 15 expansion programme 43 - Membership of a cooperative 16 Special economic zones 45 Registration 16 Alat Free Economic Zone 46 - LLC 16 - JSC 16 Intellectual property 49 - Branches or representative offices 16 Introduction 49 De-registration of companies 17 - Stage 1 17 Legislation 49 - Stage 2 18 Trademarks 50 Registration of changes 19 Patent protection of inventions, industrial designs, and utility models 50 Copyright 51 © 2019 KPMG Azerbaijan Limited. All rights reserved. Doing Business in Azerbaijan -

Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 39176 January 2007 Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement Prepared by the Road Transport Service Department for the Asian Development Bank. The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. 2 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 2 January 2007) Currency Unit – Azerbaijan New Manat/s (AZM) AZM1.00 = $1.14 $1.00 = AZM0.87 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank DRMU – District Road Maintenance Unit EA – executing agency EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan ESS – Ecology and Safety Sector IEE – initial environmental examination MENR – Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources MFF – multitranche financing facility NOx – nitrogen oxides PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance ROW – right-of-way RRI – Rhein Ruhr International RTSD – Road Transport Service Department SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SOx – sulphur oxides TERA – TERA International Group, Inc. UNESCO – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization WHO – World Health Organization WEIGHTS AND MEASURES C – centigrade m2 – square meter mm – millimeter vpd – vehicles per day CONTENTS MAP I. Introduction 1 II. Description of the Project 3 IIII. Description of the Environment 11 A. Physical Resources 11 B. Ecological and Biological Environment 13 C. -

Nagorno-Karabakh's

Nagorno-Karabakh’s Gathering War Clouds Europe Report N°244 | 1 June 2017 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Ongoing Risks of War ....................................................................................................... 2 A. Military Tactics .......................................................................................................... 4 B. Potential Humanitarian Implications ....................................................................... 6 III. Shifts in Public Moods and Policies ................................................................................. 8 A. Azerbaijan’s Society ................................................................................................... 8 1. Popular pressure on the government ................................................................... 8 2. A tougher stance ................................................................................................... 10 B. Armenia’s Society ....................................................................................................... 12 1. Public mobilisation and anger -

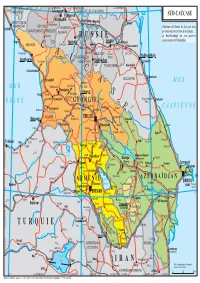

SUD-CAUCASE.Ai

vers RÉP. DES v. PSEBAÏ vers TCHERKESSK vers GUEORGUIEVSK vers ASTRAKHAN 48° TOUAPSÉ ADYGUÉS Essentouki TERRITOIRE DE STAVROPOL ï 44° Piatigorsk Kra novka SUD-CAUCASE Kislovodsk Prokhladnyï Te TERRITOIRE DE Mozdok re Karatchaïevsk Baksan Kizliar k KRASNODAR RÉP. DES L'Abkhazie et l'Ossétie du Sud sont deux Sotchi KABARDINO- Terek KARATCHAÏS-TCHERKESSES BALKARIE provinces sécessionnistes de la Géorgie. Teberda R U S S I E Le Haut-Karabagh est une province Gagra Elbrous Grozny sécessionniste de l'Azerbaïdjan. 5642 T Naltchik Nazran Goudermes ABKHAZIE C yrnyaouz Khassaviourt Kardjine Argoun Goudaouta A Beslan - Kiziliourt 5204 INGOUCHIE Ourous Mestia OSSÉTIE DU Martan Makhatchkala uri Soukhoumi T go U Alaguir Vladikavkaz Kaspiïsk kvartcheli n NORD I TCHÉTCHÉNIE Bouïnaksk Otchamtchire C Kazbek Atchissou Oni 5037 Izberbach Zougdidi A 4492 DAGUESTAN Ossétie M E R M E R Tskhaltoubo Satchkhere du Sud Koutaïssi Tskhinvali Poti Senaki Tchiatoura S Zestafoni Samtredia Tianeti Daguestanskiïe Derbent N O I R E G É O R G I E Bejta Ogni Kaspi 4127 Ozourgueti Khachouri Telavi Kvareli E C A S P I E N N E Kobouleti Borjomi Gori Mtskheta ADJARIE B TBILISSI Gourodjaani Batoumi akouriani Zaqatala r mou Akhaltsikhe Roustavi Tchnori Sa Xaçmaz Hopa Bolnissi Akhalkalaki Qax Marneouli Dedoplis-Tskaro Quba e K I e o e Ardesen ou ri 4466 Kura ra S ki D v ci Trabzon Rize Pazar Artvin Ardahan (K Bazardüzü Alaverdi ü ee Çayeli Tachir Qazax r) Siy z n Tovuz Réservoir de Sürmene 3932 Lac de Ming e çevir Çildir Spitak Idjevan Minguetchaouri e Vanadzor e Gandja (Ming çevir) -

Restructuring Extractive Economies in the Caspian Basin TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE?

Restructuring Extractive Economies in the Caspian Basin TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE? PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 441 September 2016 Natalie Koch1 Anar Valiyev2 Syracuse University ADA University The oil- and gas-rich states of the Caspian Sea basin—Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan—registered phenomenal growth throughout most of the 2000s. However, the heady days of resource-fueled development now appear to be over, and local governments are suddenly struggling to overcome massive budget deficits, devalued currencies, and overall economic stagnation. What led to the current economic crisis gripping the Caspian basin states? In what ways are state planners in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan addressing the challenges? Although many of the reforms recently announced by these governments appear dramatic and novel, they ultimately represent little deviation from the countries’ longtime development strategies, which prioritize economic modernization without political transformation. What is Happening and Why Now? 1) A triumvirate of external shocks In addition to the dramatic drop in world energy prices over the past several years, the economic crisis gripping the Caspian littoral states is rooted in two further external shock factors: the collapse of the Russian ruble after U.S.-led sanctions were imposed in 2014, and the significant slowdown in China’s economic growth and energy demands since 2015. In the decade prior to this recent triumvirate of shocks, Eurasia had become increasingly economically integrated. In addition to the well-known labor movement and remittance networks uniting Russia and its southern neighbors, the Caspian basin states also sought to diversify their export and import markets by increasing trade with China and ramping up oil and gas sales in the east. -

Ecosystems Assessment Report Azerbaijan.Pdf

Identification and implementation of adaptation response to Climate Change impact for Conservation and Sustainable use of agro-biodiversity in arid and semi-arid ecosystems of South Caucasus Ecosystem Assessment Report Baku, 2012 List of abbreviations ANAS Azerbaijan National Academy of Science EU European Union ECHAM 4 European Center HAMburg 4 IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change GIZ German International Cooperation GIS Geographical Information System GDP Gross Domestic Product GFDL Global Fluid Dynamics Model MENR Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources PRECIS Providing Regional Climate for Impact Studies REC Regional Environmental Center UN United Nations UNFCCC UN Framework Convention on Climate Change WB World Bank Table of contents List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Executive summary ............................................................................................................................................. 6 I. Introduction...................................................................................................................................................... 7 II. General ecological and socio-economic description of selected regions ....................................................... 8 2.1. Agsu district .............................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1.1. General