Restructuring America's Ground Forces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Syllabus Summer Course

Course Syllabus Summer Course Instructor Information INSTRUCTORS DR. KIMBERLY KAGAN DR. FREDERICK KAGAN LTG (RET.) JAMES DUBIK, U.S. ARMY GUEST CO-INSTRUCTORS LTG (RET.) H.R. MCMASTER GEN (RET.) CURTIS SCAPARROTTI General Information Description: Lessons are daylong; some are divided into two blocks when they address different topics. Course Materials Required Materials Readings on Microsoft Teams Books and purchases: 1. Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2014) 2. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, eds. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984) 3. Toby Dodge, Iraq: From War to a New Authoritarianism (International Institute of Strategic Studies & Routledge: 2012) 4. Stanley A. McChrystal, My Share of the Task: A Memoir (New York, NY: Portfolio/Penguin, 2014) 5. Peter Paret, Makers of Modern Strategy: from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2010) 6. Jim Scuitto, The Shadow War: Inside Russia’s and China’s Secret War to Defeat America (New York: Harper/Harper Collins, 2019) 7. Stephen Sears, Gettysburg (New York: Mariner Books Reprint, 2004) 8. John A. Warden III, The Air Campaign, Revised Edition (iUniverse: 1998) 9. Gettysburg film (https://www.amazon.com/Gettysburg-Tom-Berenger/dp/B006QPX6IG) 1 Lesson 1 July 25th TOPIC LANGUAGE & LOGIC OF WAR PURPOSE Gain foundational knowledge vital for the remainder of the course, including the levels of war framework OBJECTIVES How are militaries organized? What frameworks help us study war? How do you read a military map? 1. Learn the levels of war 2. -

Army Press January 2017 Blythe

Pfc. Brandie Leon, 4th Infantry Division, holds security while on patrol in a local neighborhood to help maintain peace after recent attacks on mosques in the area, East Baghdad, Iraq, 3 March 2006. (Photo by Staff Sgt. Jason Ragucci, U.S. Army) III Corps during the Surge: A Study in Operational Art Maj. Wilson C. Blythe Jr., U.S. Army he role of Lt. Gen. Raymond Odierno’s III (MNF–I) while using tactical actions within Iraq in an Corps as Multinational Corps–Iraq (MNC–I) illustrative manner. As a result, the campaign waged by has failed to receive sufficient attention from III Corps, the operational headquarters, is overlooked Tstudies of the 2007 surge in Iraq. By far the most in this key work. comprehensive account of the 2007–2008 campaign The III Corps campaign is also neglected in other is found in Michael Gordon and Lt. Gen. Bernard prominent works on the topic. In The Gamble: General Trainor’s The Endgame: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Petraeus and the American Military Adventure in Iraq, Iraq, from George W. Bush to Barack Obama, which fo- 2006-2008, Thomas Ricks emphasizes the same levels cuses on the formulation and execution of strategy and as Gordon and Trainor. However, while Ricks plac- policy.1 It frequently moves between Washington D.C., es a greater emphasis on the role of III Corps than is U.S Central Command, and Multinational Force–Iraq found in other accounts, he fails to offer a thorough 2 13 January 2017 Army Press Online Journal 17-1 III Corps during the Surge examination of the operational campaign waged by III creating room for political progress such as the February 2 Corps. -

Counterinsurgency in the Iraq Surge

A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in US History. By Matthew T. Buchanan Director: Dr. Richard Starnes Associate Professor of History, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Committee Members: Dr. David Dorondo, History, Dr. Alexander Macaulay, History. April, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations . iii Abstract . iv Introduction . 1 Chapter One: Perceptions of the Iraq War: Early Origins of the Surge . 17 Chapter Two: Winning the Iraq Home Front: The Political Strategy of the Surge. 38 Chapter Three: A Change in Approach: The Military Strategy of the Surge . 62 Conclusion . 82 Bibliography . 94 ii ABBREVIATIONS ACU - Army Combat Uniform ALICE - All-purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment BDU - Battle Dress Uniform BFV - Bradley Fighting Vehicle CENTCOM - Central Command COIN - Counterinsurgency COP - Combat Outpost CPA – Coalition Provisional Authority CROWS- Common Remote Operated Weapon System CRS- Congressional Research Service DBDU - Desert Battle Dress Uniform HMMWV - High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle ICAF - Industrial College of the Armed Forces IED - Improvised Explosive Device ISG - Iraq Study Group JSS - Joint Security Station MNC-I - Multi-National-Corps-Iraq MNF- I - Multi-National Force – Iraq Commander MOLLE - Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment MRAP - Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (vehicle) QRF - Quick Reaction Forces RPG - Rocket Propelled Grenade SOI - Sons of Iraq UNICEF - United Nations International Children’s Fund VBIED - Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device iii ABSTRACT A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. -

The Case for Larger Ground Forces Stanley Foundation

Bridging the Foreign Policy Divide The The Case for Larger Ground Forces Stanley Foundation By Frederick Kagan and Michael O’Hanlon April 2007 Frederick W. Kagan is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, specializing in defense transformation, the defense budget, and defense strategy and warfare. Previously he spent ten years as a professor of military history at the United States Military Academy (West Point). Kagan’s 2006 book, Finding the Target: The Transformation of American Military Policy (Encounter Books), exam- ines the post-Vietnam development of US armed forces, particularly in structure and fundamental approach. Kagan was coauthor of an influential January 2007 report, Choosing Victory: A Plan for Success in Iraq, advocating an increased deployment. Michael O’Hanlon is senior fellow and Sydney Stein Jr. Chair in foreign policy studies at the Brookings Institution, where he spe- cializes in U S defense strategy, the use of military force, and homeland security. O’Hanlon is coauthor most recently of Hard Power: the New Politics of National Security (Basic Books), a look at the sources of Democrats’ political vulnerability on national security in recent decades and an agenda to correct it. He previously was an analyst with the Congressional Budget Office. Brookings’ Iraq Index project, which he leads, is a regular feature on The New York Times Op-Ed page. e live at a time when wars not only rage national inspections. What will happen if the in nearly every region but threaten to US—or Israeli—government becomes convinced Werupt in many places where the current that Tehran is on the verge of fielding a nuclear relative calm is tenuous. -

Counterterrorism Within the Afghanistan Counterinsurgency

i [H.A.S.C. No. 111–102] COUNTERTERRORISM WITHIN THE AFGHANISTAN COUNTERINSURGENCY HEARING BEFORE THE TERRORISM, UNCONVENTIONAL THREATS AND CAPABILITIES SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION HEARING HELD OCTOBER 22, 2009 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 57–054 WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 TERRORISM, UNCONVENTIONAL THREATS AND CAPABILITIES SUBCOMMITTEE ADAM SMITH, Washington, Chairman MIKE MCINTYRE, North Carolina JEFF MILLER, Florida ROBERT ANDREWS, New Jersey FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island JOHN KLINE, Minnesota JIM COOPER, Tennessee BILL SHUSTER, Pennsylvania JIM MARSHALL, Georgia K. MICHAEL CONAWAY, Texas BRAD ELLSWORTH, Indiana THOMAS J. ROONEY, Florida PATRICK J. MURPHY, Pennsylvania MAC THORNBERRY, Texas BOBBY BRIGHT, Alabama SCOTT MURPHY, New York TIM MCCLEES, Professional Staff Member ALEX KUGAJEVSKY, Professional Staff Member ANDREW TABLER, Staff Assistant (II) C O N T E N T S CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF HEARINGS 2009 Page HEARING: Thursday, October 22, 2009, Counterterrorism within the Afghanistan Coun- terinsurgency ........................................................................................................ 1 APPENDIX: Thursday, October 22, 2009 ................................................................................... -

Iraq: Is the Escalation Working?

IRAQ: IS THE ESCALATION WORKING? HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 27, 2007 Serial No. 110–87 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 36–423PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS TOM LANTOS, California, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DAN BURTON, Indiana Samoa ELTON GALLEGLY, California DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ROBERT WEXLER, Florida EDWARD R. ROYCE, California ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York RON PAUL, Texas DIANE E. WATSON, California JEFF FLAKE, Arizona ADAM SMITH, Washington JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JOE WILSON, South Carolina GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas CONNIE MACK, Florida RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas DAVID WU, Oregon TED POE, Texas BRAD MILLER, North Carolina BOB INGLIS, South Carolina LINDA T. -

Defeating the Islamist Extremists: a Global Strategy for Combating Al Qaeda and the Islamic State

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE DEFEATING THE ISLAMIST EXTREMISTS: A GLOBAL STRATEGY FOR COMBATING AL QAEDA AND THE ISLAMIC STATE OPENING DISCUSSION: GENERAL MICHAEL T. FLYNN, US ARMY (RET.); FREDERICK W. KAGAN, AEI PANELISTS: MARY HABECK, AEI; SETH JONES, RAND CORPORATION; KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN, AEI MODERATOR: FREDERICK W. KAGAN, AEI 2:30 PM – 4:30 PM MONDAY, DECEMBER 7, 2015 EVENT PAGE: http://www.aei.org/events/defeating-the-islamist-extremists-a- global-strategy-for-combating-al-qaeda-and-the-islamic-state/ TRANSCRIPT PROVIDED BY DC TRANSCRIPTION – WWW.DCTMR.COM FREDERICK KAGAN: Live from Washington, it’s not Saturday night. Good afternoon everyone. That’s probably the extent of the levity we’ll have this afternoon talking about the topic that faces us. Thank you all very much for coming. Obviously, a very difficult time. We’ve been able to say that, I think, a lot over the last few months and I’m afraid that in the circumstances we’re probably going to be having to say that for quite some time. We are here today to talk about the state of the war with al Qaeda and ISIS globally. We had the president articulate his take on that, I suppose, last night, but I think a lot of people are understandably confused about what is actually going on and, more to the point – what should be done. I think it is not as hard to understand what’s actually going on as is being made out, but it is very difficult, I think, to figure out what to do. We have a report that we’re releasing today that is an attempt to get after that. -

Frederick Kagan on the Fall of Kabul, the Afghan a the Taliban

WTH is going on with the Taliban takeover? Frederick Kagan on the fall of Kabul, the Afghan a the Taliban Episode #114 | August 18, 2021 | Danielle Pletka, Marc Thiessen, and Frederick W. Kagan Danielle Pletka: Hi, I'm Danielle Pletka. Marc Thiessen: I'm Marc Thiessen. Danielle Pletka: Welcome to our podcast, What the Hell Is Going On? Marc, what the bloody hell is going on? Marc Thiessen: The Taliban are back in charge of Afghanistan. We are in the middle of our August hiatus that we told you all about, that we were going to take a month off because nothing ever happens in August. Apparently the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan happens in August. So we have come out of hiatus to do an emergency episode of this podcast, because what is unfolding before our eyes in Afghanistan right now is, honestly, I said this on Fox the other day, and I will repeat it here, it's the worst thing I've seen in three decades in Washington and the most horrifying thing I've seen in three decades in Washington. The betrayal of our allies, the abdication of American leadership on the world stage, the humanitarian catastrophe that was unleashed by a decision made in the Oval Office. And I'm almost at a loss for words to explain how awful the situation is. Danielle Pletka: First of all, I guess we've seen this coming. The president signaled that he wanted this to happen. I think everybody was not fooled by his, well, what can I call them? Lies, about what was going to happen. -

Afghanistan Stay Or Go

Kurt Volker: [0:01] ...illuminate some complex policy issues, giving different points of view equal and fair time and making sure that we try to take the partisanship out of the debate so we get to the real issues that underlie our options as a country. [0:14] Tonight's debate will focus on Afghanistan. America's been involved in Afghanistan for nearly 12 years. There's been remarkable progress in education, health care, women's rights, children, governance, the economy. And yet, there has come, at a cost of hundreds of billions of dollars, thousands of lives. The question remains, is it really sustainable? [0:37] We're now committed to a transition in Afghanistan, as President Obama said, ending America's war in Afghanistan by the end of 2014. But is Afghanistan ready? And what will happen when America leaves? On the other hand, would it really be any better if we stayed? [0:54] We have four distinguished panelists tonight representing four distinct perspectives on Afghanistan and US policy. We hope that their debate helps eliminate the challenges that we still face as a country. [1:05] Before introducing our moderator, allow me to introduce the man whose life and whose family has inspired the creation of this institute, the man who's dedicated his family and his career to national service, Senator John McCain. [applause] Senator John McClain: [1:22] Thank you very much, Kurt. I'd like to thank Jenna Lee, who's going to be our moderator here and our panelists, all of whom I have had the opportunity of knowing and interacting with over a number of years. -

Iraq Study Group Consultations

CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF THE PRESIDENCY IRAQ STUDY GROUP Iraq Study Group Consultations (* denotes meeting took place in Iraq) Iraqi Officials and Representatives * Jalal Talabani - President * Tareq al-Hashemi - Vice President * Adil Abd al-Mahdi - Vice President * Nouri Kamal al-Maliki - Prime Minister * Salaam al-Zawbai - Deputy Prime Minister * Barham Salih - Deputy Prime Minister * Mahmoud al-Mashhadani - Speaker of the Parliament * Mowaffak al-Rubaie - National Security Advisor * Jawad Kadem al-Bolani - Minister of Interior * Abdul Qader Al-Obeidi - Minister of Defense * Hoshyar Zebari - Minister of Foreign Affairs * Bayan Jabr - Minister of Finance * Hussein al-Shahristani - Minster of Oil * Karim Waheed - Minister of Electricity * Akram al-Hakim - Minister of State for National Reconciliation Affairs * Mithal al-Alusi - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Ayad Jamal al-Din - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Ali Khalifa al-Duleimi - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Sami al-Ma'ajoon - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation * Muhammad Ahmed Mahmoud - Member, Commission on National Reconciliation * Wijdan Mikhael - Member, High Commission on National Reconciliation Lt. General Nasir Abadi - Deputy Chief of Staff of the Iraqi Joint Forces * Adnan al-Dulaimi - Head of the Tawafuq list Ali Allawi - Former Minister of Finance * Sheik Najeh al-Fetlawi - representative of Muqtada al-Sadr * Abd al-Aziz al-Hakim - Shia Coalition Leader * Sheik Maher al-Hamraa - Ayat Allah -

Confronting the Russian Challenge: a New Approach for the U.S

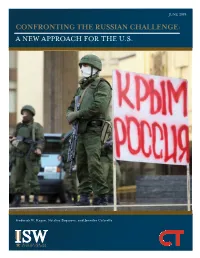

JUNE 2019 CONFRONTING THE RUSSIAN CHALLENGE: A NEW APPROACH FOR THE U.S. Frederick W. Kagan, Nataliya Bugayova, and Jennifer Cafarella Frederick W. Kagan, Nataliya Bugayova, and Jennifer Cafarella CONFRONTING THE RUSSIAN CHALLENGE: A NEW APPROACH FOR THE U.S. Cover: SIMFEROPOL, UKRAINE - MARCH 01: Heavily-armed soldiers without identifying insignia guard the Crimean parliament building next to a sign that reads: “Crimea Russia” after taking up positions there earlier in the day on March 1, 2014 in Simferopol, Ukraine. The soldiers’ arrival comes the day after soldiers in similar uniforms stationed themselves at Simferopol International Airport and Russian soldiers occupied the airport at nearby Sevastapol in moves that are raising tensions between Russia and the new Kiev government. Crimea has a majority Russian population and armed, pro-Russian groups have occupied government buildings in Simferopol. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images) All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing or from the publisher. ©2019 by the Institute for the Study of War and the Critical Threats Project. Published in 2019 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War and the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 1789 Massachusetts Avenue, NW | Washington, DC 20036 understandingwar.org criticalthreats.org ABOUT THE INSTITUTE ISW is a non-partisan and non-profit public policy research organization. -

Iraq's Budget Surplus Hearing Committee on The

IRAQ’S BUDGET SURPLUS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE BUDGET HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION HEARING HELD IN WASHINGTON, DC, SEPTEMBER 16, 2008 Serial No. 110–40 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Budget ( Available on the Internet: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/house/budget/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 44–426 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 12:28 Dec 04, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 J:\DOCS\HEARINGS\110TH\110-40\44426.TXT HBUD1 PsN: DICK COMMITTEE ON THE BUDGET JOHN M. SPRATT, JR., South Carolina, Chairman ROSA L. DELAURO, Connecticut, PAUL RYAN, Wisconsin, CHET EDWARDS, Texas Ranking Minority Member JIM COOPER, Tennessee J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina THOMAS H. ALLEN, Maine JO BONNER, Alabama ALLYSON Y. SCHWARTZ, Pennsylvania SCOTT GARRETT, New Jersey MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MARIO DIAZ–BALART, Florida XAVIER BECERRA, California JEB HENSARLING, Texas LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon MICHAEL K. SIMPSON, Idaho MARION BERRY, Arkansas PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina ALLEN BOYD, Florida CONNIE MACK, Florida JAMES P. MCGOVERN, Massachusetts K. MICHAEL CONAWAY, Texas NIKI TSONGAS, Massachusetts JOHN CAMPBELL, California ROBERT E. ANDREWS, New Jersey PATRICK J. TIBERI, Ohio ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia JON C. PORTER, Nevada BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina RODNEY ALEXANDER, Louisiana DARLENE HOOLEY, Oregon ADRIAN SMITH, Nebraska BRIAN BAIRD, Washington JIM JORDAN, Ohio DENNIS MOORE, Kansas TIMOTHY H.