Download Full Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

Marvel Comics Marvel Comics

Roy Tho mas ’Marvel of a ’ $ Comics Fan zine A 1970s BULLPENNER In8 th.e9 U5SA TALKS ABOUT No.108 MARVELL CCOOMMIICCSS April & SSOOMMEE CCOOMMIICC BBOOOOKK LLEEGGEENNDDSS 2012 WARREN REECE ON CLOSE EENNCCOOUUNNTTEERRSS WWIITTHH:: BIILL EVERETT CARL BURGOS STAN LEE JOHN ROMIITA MARIIE SEVERIIN NEAL ADAMS GARY FRIIEDRIICH ALAN KUPPERBERG ROY THOMAS AND OTHERS!! PLUS:: GOLDEN AGE ARTIIST MIKE PEPPE AND MORE!! 4 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 6 2 8 1 Art ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Human Torch & Sub-Mariner logos ™ Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 108 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) AT LAST! Ronn Foss, Biljo White LL IN Mike Friedrich A Proofreader COLOR FOR Rob Smentek .95! Cover Artists $8 Carl Burgos & Bill Everett Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Writer/Editorial: Magnificent Obsession . 2 “With The Fathers Of Our Heroes” . 3 Glenn Ald Barbara Harmon Roy Ald Heritage Comics 1970s Marvel Bullpenner Warren Reece talks about legends Bill Everett & Carl Burgos— Heidi Amash Archives and how he amassed an incomparable collection of early Timelys. Michael Ambrose Roger Hill “I’m Responsible For What I’ve Done” . 35 Dave Armstrong Douglas Jones (“Gaff”) Part III of Jim Amash’s candid conversation with artist Tony Tallarico—re Charlton, this time! Richard Arndt David Karlen [blog] “Being A Cartoonist Didn’t Really Define Him” . 47 Bob Bailey David Anthony Kraft John Benson Alan Kupperberg Dewey Cassell talks with Fern Peppe about her husband, Golden/Silver Age inker Mike Peppe. -

Other Egg Things

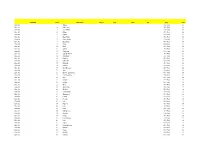

Mediterranean 9.95 With classic flair we combine mushrooms, Start Fresh bacon, chives, Swiss and Parmesan cheese, Fresh squeezed every day. Monday, Tuesday, topped sparsely with parsley. Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday and even payday. T.C. Eggington Piglet’s Passion 10.45 The founder of the Diced ham, pork sausage, bacon, green peppers, Eggington Farm olives, mushrooms, tomatoes, onions, zucchini Orange or Grapefruit Juice and Bruncheries. and assorted cheeses. Small Glass 3.45 He always said, “A day without eggs is Large Glass 3.95 just like any other Cheeses Galore 8.95 Litre 7.95 day, but without eggs.” Cheddar, Jack and Swiss, bubbly and hot… with bacon, ham, sausage OR mushrooms, add Pressed Apple Juice 95¢ each. Small Glass 3.45 Large Glass 3.95 Litre 7.95 Parlour Creations V-8 or Cranberry Juice Omelettes Please Note: The consumption of undercooked eggs Hand-picked from the shelf. Complemented by English muffins or gluten free toast could increase your risk of possible food borne illness. Small Glass 3.45 & Parlour Preserves, with choice of Parlour Potatoes, Large Glass 3.95 Fresh Fruit, Sliced Tomatoes or Cottage Cheese. *Items denoted with a star can be cooked Litre 7.95 to your preference. Cocktails Glory 10.25 This egg white only beauty is guaranteed to make Croque Monsieur 10.25 Mimosa 5 Bellini 5 you feel healthy-yet-satisfied with a tasty mix of Grilled artisan sourdough, tomato, black forest Bloody Mary 5 Screwdriver 5 marinated roma tomatoes, cilantro, avocado and ham, mustard sauce, gruyere, 2 eggs basted. red onion. -

Download Full Menu

Mediterranean 11.95 With classic flair we combine mushrooms, bacon, Start Fresh chives, Swiss and Parmesan cheese, topped sparsely Fresh squeezed every day. Monday, Tuesday, with parsley. Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday and even payday. T.C. Eggington Piglet’s Passion 12.45 The founder of the Diced ham, pork sausage, bacon, green peppers, Eggington Farm olives, mushrooms, tomatoes, onions, zucchini and Orange or Grapefruit Juice and Bruncheries. assorted cheeses. Small Glass 3.95 He always said, “A day without eggs is Large Glass 4.45 just like any other Cheeses Galore 10.95 Litre 8.95 day, but without eggs.” Cheddar, Jack and Swiss, bubbly and hot… with bacon, ham, sausage OR mushrooms, add 95¢ Pressed Apple Juice each. Small Glass 3.95 Large Glass 4.45 Litre 8.95 Parlour Creations V-8 or Cranberry Juice Omelettes Please Note: The consumption of undercooked eggs could Hand-picked from the shelf. Complemented by English muffins or gluten free toast & increase your risk of possible food borne illness. Small Glass 3.95 Parlour Preserves, with choice of Parlour Potatoes, Fresh Large Glass 4.45 Fruit, Sliced Tomatoes or Cottage Cheese. *Items denoted with a star can be cooked Litre 8.95 to your preference. Cocktails Morning Glory 12.45 This egg white only beauty is guaranteed to make *Chilaquiles 11.45 you feel healthy-yet-satisfied with a tasty mix of Try our roasted ranchero sauce atop marinated roma tomatoes, cilantro, avocado and red hand-rolled fresh corn tortillas, melted cheese, onion. 2 eggs and sprigs of celantro. Fresh Baked English Style Muffins add chicken or charizo .95 An English tradition, these homemade O’Pear Grenache Omelette 12.25 sweetcakes are unique and special. -

Wolverine & the X-Men: Volume 7 Free

FREE WOLVERINE & THE X-MEN: VOLUME 7 PDF Jason Aaron,Pasqual Ferry | 136 pages | 12 Nov 2013 | Marvel Comics | 9780785166009 | English | New York, United States Wolverine and the X-Men Vol 2 7 | Marvel Database | Fandom Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Nick Bradshaw Wolverine & the X-Men: Volume 7. Pasqual Ferry Illustrations. Meanwhile, Beast goes to the S. The storyline that's been building for over a year is finally, explosively he Students at the Jean Grey School are missing, and a furious Wolverine and Rachel Summers intensify their search for the all-new Hellfire Club. The storyline that's been building for over a year is finally, explosively here! The Hellfire Saga begins now! Collecting : Wolverine and the X-Men Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Wolverine and the X-Men, Volume 7please sign up. Be the first to ask a question about Wolverine and the X-Men, Volume 7. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Wolverine and the X-Men, Volume 7. May 17, Jeff rated it it was ok Shelves: comix. Can I get off the donkey now? The kiddie Hellfire Club has been an ongoing plot line in this series since Stan Lee was in diapers the baby kind. -

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto Mem #'d Odds Point Base Set 1 Angela 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 2 Anti-Venom 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 3 Doc Samson 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 4 Attuma 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 5 Bedlam 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 6 Black Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 7 Black Panther 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 8 Black Swan 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 9 Blade 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 10 Blink 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 11 Callisto 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 12 Cannonball 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 13 Captain Universe 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 14 Challenger 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 15 Punisher 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 16 Dark Beast 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 17 Darkhawk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 18 Collector 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 19 Devil Dinosaur 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 20 Ares 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 21 Ego The Living Planet 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 22 Elsa Bloodstone 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 23 Eros 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 24 Fantomex 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 25 Firestar 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 26 Ghost 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 27 Ghost Rider 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 28 Gladiator 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 29 Goblin Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 30 Grandmaster 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 31 Hazmat 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 32 Hercules 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 33 Hulk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 34 Hyperion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 35 Ikari 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 36 Ikaris 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 37 In-Betweener 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 38 Khonshu 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 39 Korvus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 40 Lady Bullseye 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 41 Lash 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 42 Legion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 43 Living Lightning 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 44 Maestro 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 45 Magus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 46 Malekith 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 47 Manifold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 48 Master Mold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 49 Metalhead 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 50 M.O.D.O.K. -

Marvel Comics Marvel Comics

Roy Tho mas ’Marvel of a ’ $ Comics Fan zine A 1970s BULLPENNER In8 th.e9 U5SA TALKS ABOUT No.108 MARVELL CCOOMMIICCSS April & SSOOMMEE CCOOMMIICC BBOOOOKK LLEEGGEENNDDSS 2012 WARREN REECE ON CLOSE EENNCCOOUUNNTTEERRSS WWIITTHH:: BIILL EVERETT CARL BURGOS STAN LEE JOHN ROMIITA MARIIE SEVERIIN NEAL ADAMS GARY FRIIEDRIICH ALAN KUPPERBERG ROY THOMAS AND OTHERS!! PLUS:: GOLDEN AGE ARTIIST MIKE PEPPE AND MORE!! 4 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 6 2 8 1 Art ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Human Torch & Sub-Mariner logos ™ Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 108 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) AT LAST! Ronn Foss, Biljo White LL IN Mike Friedrich A Proofreader COLOR FOR Rob Smentek .95! Cover Artists $8 Carl Burgos & Bill Everett Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Writer/Editorial: Magnificent Obsession . 2 “With The Fathers Of Our Heroes” . 3 Glenn Ald Barbara Harmon Roy Ald Heritage Comics 1970s Marvel Bullpenner Warren Reece talks about legends Bill Everett & Carl Burgos— Heidi Amash Archives and how he amassed an incomparable collection of early Timelys. Michael Ambrose Roger Hill “I’m Responsible For What I’ve Done” . 35 Dave Armstrong Douglas Jones (“Gaff”) Part III of Jim Amash’s candid conversation with artist Tony Tallarico—re Charlton, this time! Richard Arndt David Karlen [blog] “Being A Cartoonist Didn’t Really Define Him” . 47 Bob Bailey David Anthony Kraft John Benson Alan Kupperberg Dewey Cassell talks with Fern Peppe about her husband, Golden/Silver Age inker Mike Peppe. -

Marvel-Phile

by Steven E. Schend and Dale A. Donovan Lesser Lights II: Long-lost heroes This past summer has seen the reemer- 3-D MAN gence of some Marvel characters who Gestalt being havent been seen in action since the early 1980s. Of course, Im speaking of Adam POWERS: Warlock and Thanos, the major players in Alter ego: Hal Chandler owns a pair of the cosmic epic Infinity Gauntlet mini- special glasses that have identical red and series. Its great to see these old characters green images of a human figure on each back in their four-color glory, and Im sure lens. When Hal dons the glasses and focus- there are some great plans with these es on merging the two figures, he triggers characters forthcoming. a dimensional transfer that places him in a Nostalgia, the lowly terror of nigh- trancelike state. His mind and the two forgotten days, is alive still in The images from his glasses of his elder broth- MARVEL®-Phile in this, the second half of er, Chuck, merge into a gestalt being our quest to bring you characters from known as 3-D Man. the dusty pages of Marvel Comics past. As 3-D Man can remain active for only the aforementioned miniseries is showing three hours at a time, after which he must readers new and old, just because a char- split into his composite images and return acter hasnt been seen in a while certainly Hals mind to his body. While active, 3-D doesnt mean he lacks potential. This is the Mans brain is a composite of the minds of case with our two intrepid heroes for this both Hal and Chuck Chandler, with Chuck month, 3-D Man and the Blue Shield. -

THE SCRIBLERIAN Spring 2009 Edition

THE SCRIBLERIAN Spring 2009 Edition Sponsored by the English Department and the Braithwaite Writing Center, the Scriblerian is a publication for students by students. Revived during Fall Semester 2004 after a two-year hiatus, this on-line journal is the result of an essay competition organized by Writing Center tutors for ENGL 1010 and 2010 students. The Spring 2009 contest was planned and supervised by Chair Kellie Jensen with the help of Andria Amodt, Trent Gurney, Chelsea Oaks, and Whitnee Sorenson. 1 Contents Argumentative- English 1010 ........................................................................................................................ 2 1st Place Winner: Sara LaFollette, “Mr. Marvel” .................................................................................. 2 2nd Place Winner: Megan Magelby, “Rhetorical Analysis” .................................................................. 12 Expressive- English 1010 ............................................................................................................................. 15 1st Place Winner: Brittney L. Park, “Heroin Chic” ................................................................................ 15 2nd Place Winner: Kristy Stoll, “My Piano” .......................................................................................... 16 Argumentative- English 2010 ...................................................................................................................... 18 1st Place Winner: Erica Wardell, “Tragedy in Technology” -

Superhero Poster

Superhero Event Poster Stuff The following can be printed out and glued on posterboard, foamboard or even plain old cardboard. Place poster with event to increase its visual appeal as well as add a little background about the event. Please Note: the following text is mostly copied from Wiki and images were taken from Google images. There is nothing really original here. Superhero Photo Shoots Batarang Throwing A batarang is a roughly bat-shaped throwing weapon used by superhero Batman. They have since become a staple of Batman's arsenal, used for non-lethal ranged attack used to neutralize villains and hit other targets. It is often used to knock guns out of an assailant's hand. Baterangs in different forms are also used by Robin, Batgirl, NightWing, Owlman and even Catwoman. NightWing uses Wing-Dings, while Robin uses Throwing Bird - colloquially referred to as a "Birdarang". Both of these are roughly bird-shaped. Catwoman uses a Batman inspired catarangs and Owlman has his own arsenal of "razorangs". Superhero Rope Climb Unless you have the special ability to fly, you may at some point need to use a rope climb to access buildings via the roof or window or scale walls, mountains or other obstacles. Rope Climbs are frequently used by both Batman and Robin. Superhero Rope Climb Unless you have the special ability to fly, you may at some point need to use a rope climb to access buildings via the roof or window or scale walls, mountains or other obstacles. Rope Climbs are frequently used by both Batman and Robin. -

Brisson Rosenberg Thompson Asrar Rosenberg

RATED RATED ROSENBERG ASRAR THOMPSON ROSENBERG BRISSON 0 0 1 1 1 $7.99 LGY#620 US T+ 1 7 59606 09134 8 BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! They were born mutants… ED BRISSON, possessing powers of a genetic origin that made MATTHEW ROSENBERG & them outcasts of society. KELLY THOMPSON But one man—Professor Writers Charles Xavier—brought them together to learn to use their unique gifts in the service of a world that MAHMUD ASRAR hates and fears them… They Artist are Children of the Atom… RACHELLE ROSENBERG Color Artist VC’s JOE CARAMAGNA Letterer LEINIL FRANCIS YU & EDGAR DELGADO Cover Artists DAVID FINCH & FRANK D’ARMATA; JIM CHEUNG & JUSTIN PONSOR; SCOTT WILLIAMS & RYAN KINNAIRD; CARLOS PACHECO, RAFAEL FONTERIZ & EDGAR DELGADO; JOE QUESADA & RICHARD ISANOVE; ROB LIEFELD & ROMULO FAJARDO JR. Variant Cover Artists DISASSEMBLED JEFF POWELL PART 1 Title Page Design CHRIS ROBINSON Under the leadership of Katherine “Kitty” Pryde, the Assistant Editor JORDAN D. WHITE with Xavier Institute for Mutant Education and Outreach DARREN SHAN Editors has served as the latest training ground for young mutants as well as the headquarters for the mutant peacekeepers known as the X-Men. Recently Kitty was joined by long-standing X-Man Jean Grey, X-MEN CREATED BY who spearheaded her own team of X-Men for the STAN LEE & JACK KIRBY betterment of mutant and humankind alike. C.B. CEBULSKI EDITOR IN CHIEF JOE QUESADA CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER DAN BUCKLEY PRESIDENT ALAN FINE EXECUTIVE PRODUCER UNCANNY X-MEN No. 1, January 2019. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. -

Regarding the Dead: Human Remains in the British Museum Edited by Alexandra Fletcher, Daniel Antoine and JD Hill Published with the Generous Support Of

Regarding the Dead: Human Remains in the British Museum Edited by Alexandra Fletcher, Daniel Antoine and JD Hill Published with the generous support of THE FLOW FOUNDATION Publishers The British Museum Great Russell Street London wc1b 3dg Series editor Sarah Faulks Distributors The British Museum Press 38 Russell Square London wc1b 3qq Regarding the Dead: Human Remains in the British Museum Edited by Alexandra Fletcher, Daniel Antoine and JD Hill isbn 978 086159 197 8 issn 1747 3640 © The Trustees of the British Museum 2014 Front cover: Detail of a mummy of a Greek youth named Artemidorus in a cartonnage body-case, 2nd century ad. British Museum, London (EA 21810) Printed and bound in the UK by 4edge Ltd, Hockley Papers used in this book by The British Museum Press are of FSC Mixed Credit, elemental chlorine free (ECF) fibre sourced from well-managed forests All British Museum images illustrated in this book are © The Trustees of the British Museum Further information about the Museum and its collection can be found at britishmuseum.org Preface v Contents JD Hill Part One – Holding and Displaying Human Remains Introduction 1 Simon Mays 1. Curating Human Remains in Museum Collections: 3 Broader Considerations and a British Museum Perspective Daniel Antoine 2. Looking Death in the Face: 10 Different Attitudes towards Bog Bodies and their Display with a Focus on Lindow Man Jody Joy 3. The Scientific Analysis of Human Remains from 20 the British Museum Collection: Research Potential and Examples from the Nile Valley Daniel Antoine and Janet Ambers Part Two – Caring For, Conserving and Storing Human Remains Introduction 31 Gaye Sculthorpe 4.