Prokynesis Before Jesus in Its Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How 'Great' Was Alexander?

Historical Site of Mirhadi Hoseini http://m-hosseini.ir ……………………………………………………………………………………… IRANIAN HISTORY: POST-ACHAEMENIDS How ‘Great’ Was Alexander? By: Professor Ian Worthington1[1] (University of Missouri-Columbia) Why was Alexander II of Macedon called 'Great'? The answer seems relatively straightforward: from an early age he was an achiever, he conquered territories on a superhuman scale, he established an empire until his times unrivalled, and he died young, at the height of his power. Thus, at the youthful age of 20, in 336, he inherited the powerful empire of Macedon, which by then controlled Greece and had already started to make inroads into Asia. In 334 he invaded Persia, and within a decade he had defeated the Persians, subdued Egypt, and pushed on to Iran, Afghanistan and even India. As well as his vast conquests Alexander is credited with the spread of Greek culture and education in his empire, not to mention being responsible for the physical and cultural formation of the Hellenistic kingdoms — some would argue that the Hellenistic world was Alexander's legacy.[2[2]] He has also been viewed as a philosophical idealist, striving to create a unity of mankind by his so-called fusion of the races policy, in which he attempted to integrate Persians and Orientals into his administration and army. Thus, within a dozen years Alexander’s empire stretched from Greece in the west to India in the far east, and he was even worshipped as a god by many of his subjects while still alive. On the basis of his military conquests contemporary -

Embodied Liturgy

1 Bodies and Liturgy A. Bodies Created to Worship God This is an introductory journey in liturgy. As such, we will cover many of the basics of liturgics and the repertoire of liturgical rites. However, our journey will proceed, as far as possible, from the perspective of the human body engaged in acts of worship. The premise is that we have nothing else with which to worship God than our bodily selves. This is something that should be self-evident, but worship as a bodily act hasn’t been given a great deal of attention. Most of us, especially Westerners, think of ourselves as minds with a body attached. Our religion, too, is primarily a matter of thought and feeling rather than bodily actions. In fact, we tend to look down on those whose religion is just “going through the motions,” forgetting that we must start somewhere—such as getting out of bed on Sunday morning to go to church. In a time when more and more people in Western societies get out of bed on Sunday morning to go jogging or biking or to take their kids to soccer practice because they generally find worship boring and unengaging, perhaps we need to give some attention to the role of the body in worship. 1 EMBODIED LITURGY Many of us need to begin giving some attention to the body. Unless we are athletes or singers or make our living by using our bodies, we don’t pay a lot of attention to our bodies until we are sick. This is what happened to me. -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

"So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 20 (2011-2012) Issue 3 Article 5 March 2012 Kiss the Book...You're President...: "So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office Frederick B. Jonassen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Repository Citation Frederick B. Jonassen, Kiss the Book...You're President...: "So Help Me God" and Kissing the Book in the Presidential Oath of Office, 20 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 853 (2012), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol20/iss3/5 Copyright c 2012 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj KISS THE BOOK . YOU’RE PRESIDENT . : “SO HELP ME GOD” AND KISSING THE BOOK IN THE PRESIDENTIAL OATH OF OFFICE Frederick B. Jonassen* INTRODUCTION .................................................854 I. THE LEGAL SIGNIFICANCE OF “SO HELP ME GOD” AS HISTORICAL PRECEDENT IN THE PRESIDENT’S INAUGURATION ...................859 A. Washington’s “So Help Me God” in the Supreme Court ..........861 B. Newdow v. Roberts.......................................864 II. THE CASE AGAINST “SO HELP ME GOD”..........................870 A. The Washington Irving Recollection ..........................872 B. The Freeman Source ......................................874 C. Two Conjectural Arguments for “So Help Me God” Discredited ...879 D. One More Conjecture .....................................881 III. THE EVIDENCE THAT WASHINGTON KISSED THE BIBLE ..............885 A. First-Hand Accounts of the Biblical Kiss ......................885 B. The Subsequent Tradition ..................................890 1. Andrew Johnson......................................892 2. Ulysses S. Grant......................................892 3. Rutherford B. Hayes...................................893 4. James A. -

Persianism in Antiquity

Oriens et Occidens – Band 25 Franz Steiner Verlag Sonderdruck aus: Persianism in Antiquity Edited by Rolf Strootman and Miguel John Versluys Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2017 CONTENTS Acknowledgments . 7 Rolf Strootman & Miguel John Versluys From Culture to Concept: The Reception and Appropriation of Persia in Antiquity . 9 Part I: Persianization, Persomania, Perserie . 33 Albert de Jong Being Iranian in Antiquity (at Home and Abroad) . 35 Margaret C. Miller Quoting ‘Persia’ in Athens . 49 Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones ‘Open Sesame!’ Orientalist Fantasy and the Persian Court in Greek Art 430–330 BCE . 69 Omar Coloru Once were Persians: The Perception of Pre-Islamic Monuments in Iran from the 16th to the 19th Century . 87 Judith A. Lerner Ancient Persianisms in Nineteenth-Century Iran: The Revival of Persepolitan Imagery under the Qajars . 107 David Engels Is there a “Persian High Culture”? Critical Reflections on the Place of Ancient Iran in Oswald Spengler’s Philosophy of History . 121 Part II: The Hellenistic World . 145 Damien Agut-Labordère Persianism through Persianization: The Case of Ptolemaic Egypt . 147 Sonja Plischke Persianism under the early Seleukid Kings? The Royal Title ‘Great King’ . 163 Rolf Strootman Imperial Persianism: Seleukids, Arsakids and Fratarakā . 177 6 Contents Matthew Canepa Rival Images of Iranian Kingship and Persian Identity in Post-Achaemenid Western Asia . 201 Charlotte Lerouge-Cohen Persianism in the Kingdom of Pontic Kappadokia . The Genealogical Claims of the Mithridatids . 223 Bruno Jacobs Tradition oder Fiktion? Die „persischen“ Elemente in den Ausstattungs- programmen Antiochos’ I . von Kommagene . 235 Benedikt Eckhardt Memories of Persian Rule: Constructing History and Ideology in Hasmonean Judea . -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Scout Uniform, Scout Sign, Salute and Handshake

In this Topic: Participation Promise and Law Scout Uniform, Scout Salute and Scout Handshake Scouts and Flags Scouting History Discussion with the Scout Leader Introducing Tenderfoot Level The Journey Life in the Troop is a journey. As in any journey one embarks on, there needs to be proper preparation for the adventure ahead. This is important so as to steer clear of obstacles and perils, which, with good foresight, can often be avoided. As Scouts we follow our simple motto: Be Prepared! With this in mind you can start your preparations for the journey ahead… The Tenderfoot This level offers a starting point for a new member in the troop. For those Cubs whose time has come to move up from the pack, the Tenderfoot level is a stepping stone linking the pack with the troop. For those scouts who have joined from outside the group, this will be the beginning of their scouting life. How do I achieve this level? The five sections in this level can be done in any order. If you are a Cub Scout moving up from the pack, you will have already started the Cub Scout link badge. The Tenderfoot level is started at the same time. As you can see some of the requirements are the same for both awards. If you have just joined the scouting movement as part of the troop, this level will provide you with all the basic information to help you learn what scouting is all about. Look at the sheet on the next page so that you are able to keep track of your progress. -

Boy Scout Joining Requirements

Other Joining Requirements from page 4 of the Boy Scout Handbook Demonstrate the Scout Sign, Salute, and Handshake Scout Sign The Scout sign shows you are a Scout. Give it each time you recite the Scout Oath and Law. When a Scout or Scouter raises the Scout sign, all Scouts should make the sign, too, and come to silent attention. To give the Scout sign, cover the nail of the little finger of your right hand with your right thumb, then raise your right arm bent in a 90-degree angle, and hold the three middle fingers of your hand upward. Those fingers stand for the three parts of the Scout Oath. Your thumb and little finger touch to represent the bond that unites Scouts through out the world. Scout Salute The Scout salute shows respect. Use it to salute the flag of the United States of America. You may also salute a Scout leader or another Scout. Give the Scout salute by forming the Scout sign with your right hand and then bringing that hand upward until your forefinger touches the brim of your hat or the arch of your right eyebrow. The palm of your hand should not show. Scout Handshake The Scout handshake is made with the hand nearest the heart and is offered as a token of friendship. Extend your left hand to another Scout and firmly grasp his left hand. The fingers do not interlock. Describe the Scout Badge The badge is shaped like the north point on an old compass. The design resembles an arrowhead or a trefoil – a flower with three leaves. -

Pastor's Meanderings 13 – 14 July 2019

PASTOR’S MEANDERINGS 13 – 14 JULY 2019 FIFTEENTH SUNDAY ORDINARY TIME (C) SUNDAY REFLECTION The word ‘communion’ aptly resumes the meaning of today’s celebration. By loving, caring for others we commune, we are united with God. In Jesus, who is one with God, the whole of creation communes with God. The Church as Jesus’s body communes with Him. Our communion with Christ in the sacrament of the Eucharist is, therefore, the supreme expression and realization of God’s plan for the universe. At this moment let us meditate on this fact and resolve to lead our daily lives accordingly, trying always to behave in a Spirit of communion with others, to made real the unity of all things in Jesus. A woman in a red car one day drove up to a toll-booth and handed the attendant six tickets with the remark that she would like to pay for the next six cars. As each car stopped, the driver was told that a lady in a red car had paid their toll. She was inspired by a sentence written by Anne Herbert ‘Practice random kindness and senseless acts of beauty.’ Anne believed that random kindness is capable of generating a tidal wave just as random violence is. Could I try to do something like this and break through the safe routine of my life? STEWARDSHIP: The good Samaritan was also a good steward, giving his time and his treasure to meet his neighbor’s need. At the end of this familiar story, Jesus urges His hearers – and us – to go and do the same! Nachman of Bratslav “If we do not help a man in trouble it is as if we caused the trouble.” READINGS FOR SIXTEENTH SUNDAY 21 JUL ‘19 Gn. -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

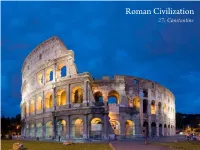

27 Constantine.Key

Roman Civilization 27: Constantine Administrative Stuf Paper III • Tesis and Topic Sentences: Due Now Midterm II • Tursday! Class website • htp://www.unm.edu/~cjdietz/romanciv/ • Updated. Administrative Stuf Paper III • Due: May 10, 5:30 p.m. Course Evaluations • Your feedback is requested. • You should have received an email from UNM. Check your email. Fall Semester: • Greek Civilization • MW 5:30-6:45 • Registration is open! • Tell your fiends! Questions? Te Dominate Starting with Diocletian Diocletian November 20, 284 - May 1, 305 Rise to Power • Born: December 2, 244 in Spalatum (Split, Croatia) • Emperor on November 20, 284 • Te Dominate (fr. Dominus) Te Dominate Starting with Diocletian Principate to Dominate • Imperator to Dominus • No longer concerned with any illusions of a republic • Dominus as divine • Proskynesis • Luxury palaces • Diocletian’s Palace Diocletian’s Palace, Split, Croatia Diocletian November 20, 284 - May 1, 305 Tetrarchy • Knew empire was too big to manage efectively • In 286, named Maximian co-emperor Tetrarchy Caesares and Augusti Tetrarchy March 1, 293 Empire was too big to manage, even with two emperors • Tetrarchy = tetra + archy (cf. monarchy) • East • Augustus: Diocletian • Caesar: Galerius • West • Augustus: Maximian • Caesar: Constantius Te Tetrarchy Confusing Tetrarchy Caesares and Augusti East West Augustus Diocletian Maximian Abdicated: May 1, 305 Abdicated: May 1, 305 Caesar Galerius Constantius Confusing Tetrarchy Caesares and Augusti East West Augustus Galerius Constantius Died July 25, 306 Caesar -

Tibetan Salutations and a Few Thoughts Suggested by Them

110 TIBETAN SALUTATIONS. TIBETAN SALUTATIONS AND A FEW THOUGHTS SUGGESTED BY THEM. (Read on 28th January 1914.) Presidenl-Lt.-Col. K. R. KIRTlKAR, LM.S. (Retd.). Salutations are of two kind8. 1. Oral or by spoken words, and 2. Gestural, or by certain movements of some parts of the body. Out of these two heads, the Tibeta:n salutations, of which I propose to speak a little to-day, fall under the second head, viz., Gestural salutations. Colonel Waddell thus speaks of the Tibetan mode of saluta tion. "The different modes of salutation Different travel· lers on the modes were curiously varied amongst the several of salutation. Col. nationalities. ,The Tibetan doffs his cap WaddeU. with his right hand and making a bow pushes forward his left ear and puts out his tongue, which seems to me to be an excellent example of the' self surrender of the person saluting to the individual he salutes,' which Herbert Spencer has shown to lie at the bottom of many of our modern practices of salutations. The pushing forward of the left ear evidently recalls the old Chinese practice of cutting off the left ears of prisoners of war, and presenting them to the victorious chief." 1 Mons. L. De Milloue thus refers to the Tibetan mode of salutation: (I translate from his French.) M. L. De Milloue. "Politeness is one of the virtues of the Tibetan. He salutes by taking off his cap as in Europe and remains bareheaded before every person whom he respects; but by a strange usage, when he wishes to be particularly amiable and polite, he completes his salutation by two gestures which appear at least strange to us: he draws the tongue rounding it a little and scratches his ears.