TAILORED SUIT the Tailored Suit Is a Garment for Women Consisting of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incontinence Care Now You Really Can Have It All

Incontinence care Now you really can have it all Clinicians can have the product quality they want. You can have the savings you need. And patients, the dignity they deserve. It doesn’t have to be complicated. Contents Briefs 4 Underwear 8 Pants 12 Insert pads 14 Premium underpads 16 Standard underpads 18 Juvenile care 20 Index 22 1 Collaboration is key To combat the effects of incontinence, we work closely with clinicians. Listening to their concerns and ideas about the products that can help solve their problems. Guided by that perspective, we develop new, advanced technologies. And a simplified set of products to help you save as you care for incontinence. Put advanced technology to work for you Guided by experienced hands — yours to deliver care, ours to deliver the most effective solutions — our products deliver the most effective solutions. Together, we can lessen the effects of incontinence on your patients’ quality of life, as well as your organization’s bottom line. Our advanced technology features: • A nonwoven hydrophilic layer that is soft and durable • Super absorbent polymer (SAP) to draw fluid away from the skin, locking it in the product’s core • An advanced core design that improves absorption rates and skin dryness 2 Choosing the right products Product Absorbency Indication for use Briefs Moderate • Severe urinary output or drainage Heavy • Loss of bowel control Extra Heavy Maximum Night-Time Underwear Moderate • Moderate to severe urinary output Heavy • Loss of bowel control Extra Heavy Maximum Knit and mesh pants • -

Lolita PETRULION TRANSLATION of CULTURE-SPECIFIC ITEMS

VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF THE LITHUANIAN LANGUAGE Lolita PETRULION TRANSLATION OF CULTURE-SPECIFIC ITEMS FROM ENGLISH INTO LITHUANIAN AND RUSSIAN: THE CASE OF JOANNE HARRIS’ GOURMET NOVELS Doctoral Dissertation Humanities, Philology (04 H) Kaunas, 2015 UDK 81'25 Pe-254 This doctoral dissertation was written at Vytautas Magnus University in 2010-2014 Research supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ingrida Egl Žindžiuvien (Vytautas Magnus University, Humanities, Philology 04 H) ISBN 978-609-467-124-1 2 VYTAUTO DIDŽIOJO UNIVERSITETAS LIETUVI KALBOS INSTITUTAS Lolita PETRULION KULTROS ELEMENT VERTIMAS IŠ ANGL LIETUVI IR RUS KALBAS PAGAL JOANNE HARRIS GURMANIŠKUOSIUS ROMANUS Daktaro disertacija, Humanitariniai mokslai, filologija (04 H) Kaunas, 2015 3 Disertacija rengta 2010-2014 metais Vytauto Didžiojo universitete Mokslin vadov: prof. dr. Ingrida Egl Žindžiuvien (Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas, humanitariniai mokslai, filologija 04 H) 4 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my research supervisor Prof. Dr. Ingrida Egl Žindžiuvien for her excellent guidance and invaluable advices. I would like to thank her for being patient, tolerant and encouraging. It has been an honour and privilege to be her first PhD student. I would also like to thank the whole staff of Vytautas Magnus University, particularly the Department of English Philology, for both their professionalism and flexibility in providing high-quality PhD studies and managing the relevant procedures. Additional thanks go to the reviewers at the Department, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Irena Ragaišien and Prof. Dr. Habil. Milda Julija Danyt, for their valuable comments which enabled me to recognize the weaknesses in my thesis and make the necessary improvements. I would like to extend my sincere thanks to my home institution, Šiauliai University, especially to the Department of Foreign Languages Studies, who believed in my academic and scholarly qualities and motivated me in so many ways. -

Glossary of Sewing Terms

Glossary of Sewing Terms Judith Christensen Professional Patternmaker ClothingPatterns101 Why Do You Need to Know Sewing Terms? There are quite a few sewing terms that you’ll need to know to be able to properly follow pattern instructions. If you’ve been sewing for a long time, you’ll probably know many of these terms – or at least, you know the technique, but might not know what it’s called. You’ll run across terms like “shirring”, “ease”, and “blousing”, and will need to be able to identify center front and the right side of the fabric. This brief glossary of sewing terms is designed to help you navigate your pattern, whether it’s one you purchased at a fabric store or downloaded from an online designer. You’ll find links within the glossary to “how-to” videos or more information at ClothingPatterns101.com Don’t worry – there’s no homework and no test! Just keep this glossary handy for reference when you need it! 2 A – Appliqué – A method of surface decoration made by cutting a decorative shape from fabric and stitching it to the surface of the piece being decorated. The stitching can be by hand (blanket stitch) or machine (zigzag or a decorative stitch). Armhole – The portion of the garment through which the arm extends, or a sleeve is sewn. Armholes come in many shapes and configurations, and can be an interesting part of a design. B - Backtack or backstitch – Stitches used at the beginning and end of a seam to secure the threads. To backstitch, stitch 2 or 3 stitches forward, then 2 or 3 stitches in reverse; then proceed to stitch the seam and repeat the backstitch at the end of the seam. -

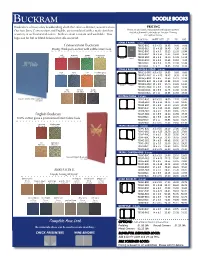

Buckram Is a Heavy-Duty Bookbinding Cloth That Offers a Distinct, Woven Texture

B UCKRAM BOODLE BOOKS Buckram is a heavy-duty bookbinding cloth that offers a distinct, woven texture. PRICING Our two lines, Conservation and English, are formulated with a matte finish in Prices are per book, nonpadded with square corners. Includes Summit Leatherette or Arrestox B lining. a variety of well-saturated colors. Both are stain resistant and washable. Your See options below. logo can be foil or blind debossed or silk screened. PART No. SHEET SIZE 25 50 100 SINGLE PANEL 1 view Conservation Buckram 7001C-BUC 8.5 x 5.5 10.95 9.80 8.60 Strong, thick poly-cotton with subtle linen look 7001D-BUC 11 x 4.25 10.45 9.30 8.10 logo 7001E-BUC 11 x 8.5 13.25 12.10 10.90 7001F-BUC 14 x 4.25 11.55 10.40 9.20 red maroon green army green CBU-RED CBU-MAR CBU-GRN CBU-AGR 7001G-BUC 14 x 8.5 14.40 13.25 12.10 front back 7001H-BUC 11 x 5.5 11.65 10.50 9.30 7001I-BUC 14 x 5.5 12.75 11.60 10.40 7001J-BUC 17 x 11 19.65 18.50 17.30 SINGLE PANEL - DOUBLE-SIDED 2 views royal navy rust medium grey 7001C/2-BUC 8.5 x 5.5 10.95 9.80 8.60 CBU-ROY CBU-NAV CBU-RUS CBU-MGY 7001D/2-BUC 11 x 4.25 10.45 9.30 8.10 7001E/2-BUC 11 x 8.5 13.25 12.10 10.90 7001F/2-BUC 14 x 4.25 11.55 10.40 9.20 front back 7001G/2-BUC 14 x 8.5 14.40 13.25 12.10 7001H/2-BUC 11 x 5.5 11.65 10.50 9.30 tan brown black 7001I/2-BUC 14 x 5.5 12.75 11.60 10.40 CBU-TAN CBU-BRO CBU-BLK 7001J/2-BUC 17 x 11 19.65 18.50 17.30 DOUBLE PANEL 2 views Royal Conservation Buckram 7002C-BUC 8.5 x 5.5 18.50 17.20 15.80 CBU-ROY 7002D-BUC 11 x 4.25 19.15 17.80 16.45 7002E-BUC 11 x 8.5 23.30 21.80 20.40 7002F-BUC -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Huggies Jeans Diapers Back on Store Shelves Just in Time for Summer

Huggies Jeans Diapers Back on Store Shelves Just in Time for Summer May 9, 2011 Huggies Jeans Diapers Back on Store Shelves Just in Time for Summer DALLAS, May 9, 2011 -Just in time for warm weather, Huggies brand is encouraging parents to dress their little ones "Cute for a Cause" with the much anticipated return of the limited-edition Huggies Jeans Diaper. By purchasing Huggies Jeans Diapers moms across North America can help a baby in need through Huggies Every Little Bottom program. One in three American Moms and one in five Canadian Moms have faced the choice between diapers and other basic needs like food. Through the Every Little Bottom program, Huggies brand will donate 22.5 million diapers in 2011. In order to help even more babies in need, Huggies brand is also enlisting parents nationwide to get involved. For every pack of Huggies Jeans Diapers, or new this year, Huggies Jeans Wipes purchased, Huggies Every Little Bottom program will help diaper a baby in need. "Diaper need in North America is an overlooked issue and Huggies is proud to serve as the leading diaper brand committed to raise awareness of this growing issue by spreading the word and helping as many families as possible," said Erik Seidel, Vice President, Huggies brand. "While Huggies is dedicated to ensuring families across North America have access to diapers, we know that an effective long-term solution weighs heavily on the support of partner organizations, grassroots efforts and most importantly, Moms who understand the importance of clean, dry diapers. "This summer, we are encouraging parents all across North America to help contribute to this cause by purchasing packages of the limited-edition Huggies Jeans diapers and wipes. -

Uniform Policy & Pricing

ALL STUDENTS MUST Noble Academy is a uniform school. BE IN UNIFORM EVERY DAY. We believe that clothing should not If your child is not in proper uniform when they come to be an obstacle to learning. school, the parent or guardian will be called to bring your child a proper uniform. Children in the kindergarten and Mission Statement 1st grade will be expected to have in the classroom an The mission of Noble Academy is to provide quality, relevant extra outfit in case of bathroom accidents. and multicultural education for all children. The Unique framework is relevancy, which is a critical component for the The following items are not allowed learning process if and when the students can build on their prior Caps, scarves, bandanas, du-rags, visors or sports knowledge. Learning makes more sense and is more connected Uniform when students can relate to the content and/or topics being bands are not allowed in the head, arms or legs. taught. This school will serve students ages 5-14 in the metro Hats and scarves are only allowed on the outdoor Policy areas. Noble Academy will focus on these four cornerstones field trips and during the winter. Authentic cultural surrounding the educational philosophy of the school: headdress can be worn when appropriate. & A rigorous educational program focusing on core content Outdoor jackets are not allowed during the school areas and standards mandated by the state of Minnesota in Pricing day unless needed for traveling to and from school. reading, writing, mathematics, science, and social studies No cargo pants , leggings, jeggings , sweatpants or Heritage (native) language and culture jeans. -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

Fashion Arts. Curriculum RP-54. INSTITUTION Ontario Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 048 223 SP 007 137 TITLE Fashion Arts. Curriculum RP-54. INSTITUTION Ontario Dept. of Education, Toronto. PUB LATE 67 NOTE 34p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Clothing Instruction, *Curriculum Guides, Distributive Education, *Grade 11, *Grade 12, *Hcme Economics, Interior Design, *Marketing, Merchandising, Textiles Instruction AESTRACT GRADES OR AGES: Grades 11 and 12. SUBJECT MATTER: Fashicn arts and marketing. ORGANIZATION AND PHkSTCAL APPEARANCE: The guide is divided into two main sections, one for fashion arts and one for marketing, each of which is further subdivided into sections fcr grade 11 and grade 12. Each of these subdivisions contains from three to six subject units. The guide is cffset printed and staple-todnd with a paper cover. Oi:IJECTIVE3 AND ACTIVITIES' Each unit contains a short list of objectives, a suggested time allotment, and a list of topics to he covered. There is only occasional mention of activities which can he used in studying these topics. INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS: Each unit contains lists of books which relate either to the unit as a whole or to subtopics within the unit. In addition, appendixes contain a detailed list of equipment for the fashion arts course and a two-page billiography. STUDENT A. ,'SSMENT:No provision. (RT) U $ DEPARTMENT OF hEALTH EOUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF THIS DOCUMENTEOUCATION HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACT' VAS RECEIVED THE PERSON OR FROM INAnNO IT POINTSORGANIZATION ()RIG IONS STATED OF VIEW OR DO NUT OPIN REPRESENT OFFICIAL NECESSARILY CATION -

View Spring Catalogue

Adaptive Clothing & Footwear Spring/Summer 2021 Simplified Dressing For Empowered Living Shop our men’s and women’s wear at silverts.com Caregiver Trusted Smart buys approved by our community experts pg 42 Stress-Free Styles E asy o and easy o f footwear pg 26 Getting Started Discover our adaptive kits made for every need pg 74 1 2 Carefree Comfort We’re always thinking about how to bring more joy to your day. That begins with exploring fresh ideas and one of them is our new catalog. It’s debuting a look that’s bright, stylish and easy on the eyes. On these pages, you’ll see all our new styles, fabrics and details that make getting dressed that much easier. We’re also sharing must-haves from our new Caregiver Trusted program. On page 42, discover the tried and true products that our community of caregivers relies on because they promise function, dignity and grace. Want some good advice? On page 74, you’ll find our needs-based kits, which have been thoughtfully curated by industry professionals. We’ve taken the guessing out of what you need to get started with any adaptive wear lifestyle. And remember, this catalog is just a snapshot of all our innovations and styles. Visit Silverts.com to see our entire collection. After a challenging year, our team is in awe of your resilience and we’re inspired to embrace these warmer days with the fresh sense of hope and spirit of togetherness that you share with us every day. Thank you for making Silverts a part of your life. -

Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’S University, Too [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2014 Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’s University, [email protected] Yuka Matsumoto Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Art Practice Commons Sano, Toshiyuki and Matsumoto, Yuka, "Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands" (2014). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 885. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/885 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano and Yuka Matsumoto This article is based on a fieldwork project we conducted in 2013 and 2014. The objective of the project was to grasp the current state of how people are engaged in the traditional ways of weaving, dyeing and making cloth in the Ryukyu Islands.1 Throughout the project, we came to think it important to understand two points in order to see the direction of those who are engaged in manufacturing textiles in the Ryukyu Islands. The points are: the diversification in ways of engaging in traditional cloth making; and the importance of multi-generational relationship in sustaining traditional cloth making. -

Integrating Malaysian and Japanese Textile Motifs Through Product Diversification: Home Décor

Samsuddin M. F., Hamzah A. H., & Mohd Radzi F. dealogy Journal, 2020 Vol. 5, No. 2, 79-88 Integrating Malaysian and Japanese Textile Motifs Through Product Diversification: Home Décor Muhammad Fitri Samsuddin1, Azni Hanim Hamzah2, Fazlina Mohd Radzi3, Siti Nurul Akma Ahmad4, Mohd Faizul Noorizan6, Mohd Ali Azraie Bebit6 12356Faculty of Art & Design, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Melaka 4Faculty of Business & Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Melaka Authors’ email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Published: 28 September 2020 ABSTRACT Malaysian textile motifs especially the Batik motifs and its product are highly potential to sustain in a global market. The integration of intercultural design of Malaysian textile motifs and Japanese textile motifs will further facilitate both textile industries to be sustained and demanded globally. Besides, Malaysian and Japanese textile motifs can be creatively design on other platforms not limited to the clothes. Therefore, this study is carried out with the aim of integrating the Malaysian textile motifs specifically focuses on batik motifs and Japanese textile motifs through product diversification. This study focuses on integrating both textile motifs and diversified the design on a home décor including wall frame, table clothes, table runner, bed sheets, lamp shades and other potential home accessories. In this concept paper, literature search was conducted to describe about the characteristics of both Malaysian and Japanese textile motifs and also to reveal insights about the practicality and the potential of combining these two worldwide known textile industries. The investigation was conducted to explore new pattern of the combined textiles motifs.