Apo-Nid8068.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drinking Water Quality Report

DRINKING WATER QUALITY REPORT 2014 -2015 Contents Dear Customers, Each year Unitywater publishes this report to set out transparently information about the quality of the drinking water Message from the CEO .........................................................3 we supply. I’m pleased to confirm that during 2014-15 the water supplied to our customers remained of a very high standard and, Our supply area ......................................................................4 as in previous years, met all regulatory requirements. Water supply sources ............................................................6 Unitywater continues to meet the requirements set by the Water quality summary ........................................................8 Queensland Public Health Regulation for drinking water, with Your suburb and its water supply region ......................... 10 99.9% of all samples free of E. coli, an indicator of possible contamination. Meeting this requirement demonstrates that Drinking water quality performance ................................. 12 you can continue to have confidence in the water supplied by Microbiological performance in detail .............................. 13 Unitywater to your home, school and work place. To maintain that confidence Unitywater sampled and completed almost Chemical performance in detail ......................................... 14 100,000 individual water tests. Of those only five did not meet an individual guideline. Each of these was investigated promptly Bribie Island ................................................................... -

Ipswich in Nation's Top 10 Property Hotspots

Ipswich in Nation’s top 10 property hotspots JESSIE RICHARDSON | 26 AUGUST 2014 IPSWICH real estate capital growth is tipped to double the return of Brisbane properties in three years, experts predict. The property market’s recovery is expected to continue this year with signs of brighter future on the horizon. But the three-year outlook is promising, according to real estate analyst and hotspotting.com.au founder Terry Ryder. Mr Ryder expects the capital growth of Ipswich properties to rise by 15% over the next three years, compared with 7.5% in Brisbane properties. Whether or not Ipswich does perform as expected remains to be seen, but I have long viewed the city as one with great investment opportunity and in a real estate investment market that is still a little hit and miss at the moment, all indicators are that Ipswich is one of the safer bets in 2013. Big projects coming for Ipswich, in Brisbane's south west, include the $2.8 billion Ipswich Motorway Upgrade, $12 billion Springfield project, the $1.5 billion Springfield rail link and the Orion shopping centre, along with expansions to the RAAF base, and large industrial estates. Ryder also claims the area has a strong economy, with multiple employment hubs and affordable properties. "The Ipswich corridor is now well-known as a growth region. Prices rose strongly in the five years to 2009 (before tapering off), giving the suburbs of Ipswich City the strongest capital growth averages in the Greater Brisbane region," writes Ryder. "Ipswich has shown strong growth in the past but we believe its evolution into a headline hotspot of national standing will continue well into the future. -

Redcliffe Peninsula Game & Sportfish Club Bream Monitoring

Recreational Fishery Monitoring Plan Title: Redcliffe Peninsula Game & Sportfish Club Bream monitoring. Q1: What do you intend to monitor? Yellowfin Bream, Acanthopagrus australis http://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/672 Other species identified by Fisheries Queensland or third party researchers Q2: Where will you monitor? Primarily in Moreton Bay and it’s canals and estuaries. Grid W37 Other areas identified by Fisheries Queensland or third party researchers. Q3: Why is this species and area a priority for monitoring? This species is a major component of the recreational and commercial fisheries throughout Moreton Bay and the Redcliffe Peninsula, both from boats and land based fishers. Little is known about their migration pattern and spawning grounds in this area. With the newly installed artificial reef being built just off the Scarborough foreshore, information regarding the migration of the bream around the estuaries and canals to and from the artificial reef would be collected and used to further understand these species and to help recreational fishers and tourist to better understand aggregation patterns, movement patterns, population patterns and Post-capture survival rates of the fish as they are increasingly being targeted by recreational fishers particularly the younger generation. Q4: Who will use your data? 1. Redcliffe Peninsula Game & Sportfish Club Inc. 2. ANSA QLD 3. Wider community 4. Third Party Researchers ** All data remains the property of Redcliffe Peninsula Game and Sportfish Club Inc. and cannot be reprinted, published, analysed or used in whole or part without the express written permission of the above mention club with an exception granting ANSA QLD authority to analyse, display and promote the data and results, but not distribute to other third parties without prior consent and that this authority can be withdrawn at any time by written notice. -

If You Have Issues Viewing Or Accessing This File Contact Us at NCJRS.Gov

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. o ft: o ·.:7· (J :::0 Q rr·--"r: --.....---.~- ;,... --T' :~. ,~.;,- .~, -A'1'<'~:_"";.,' . • ~~ _: . r '-c--:",_ ' "- ~'- ,,- " -~, . I' ,. , .... ' , . '" f" Front cover: The solitude of policing in the Queensland Outback is typified ~, , ;'!. \ in this photograph of Senior Constable Gordon THOMAS contacting his tliise station while on patrol west of Bird~)Jille near the South Australian border. 1619 kilometres by road from Brisbane. "'t''''-:-' " Rear cover: • Police activity in one of the most remote country areas of the State ... (Top left) Time for an early morning. chat outside the Birdsville Hotel with the town's publican. (Top right) The Birdsville Police StatIon. home .for the District's only policeman, Senior Constable Gordon ·tHOMAS. (Bottom left) Convoy of travellers seeking police 'assistance in Birdsville, on road conditions and directions before continuing their Journey. (Bottom right). Senior Constable THOMAS swapping storIes with a local stockman durIng his rounds. , . , QUEENSLAND POLICE DEPARTMENT ANNUAL REPORT 1 918 REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER OF POLICE, Mr T. M. LEWIS, G.M., Q.P.M., Dip.Pub.Admin., B.A. FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 1978 N(!J RS· JUl251979 PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT BY COMMAND ACQUISfT~ONS By Authority: S. R. HAMPSOI'f, Government Printer, Brisbane INSIGNIA OF RANK COMMISSIONER CHIEF SUPERINTENDENT SUPERINTENDENT GRADE 1 SUPERINTENDENT GRADE 2 INSPECTOR GRADE 1 INSPECTOR GRADE 2 INSPECTOR GRADE 3 INSPECTOR GRADE 4 SERGEANT l/e SENIOR COI'ISTABI.E CONSTABI.E l/e CONSTABI.E QUEENSLAND POLICE DEPARTMENT OFFICE OF COMMISSIONER OF POLICE 9th November, 1978 The Honourable The Minister for Mines, Energy and Police Brisbane Sir, I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of the Queensland Police Department for the twelve months ended June 30, 1978. -

Aboriginal Camps As Urban Foundations? Evidence from Southern Queensland Ray Kerkhove

Aboriginal camps as urban foundations? Evidence from southern Queensland Ray Kerkhove Musgrave Park: Aboriginal Brisbane’s political heartland In 1982, Musgrave Park in South Brisbane took centre stage in Queensland’s ‘State of Emergency’ protests. Bob Weatherall, President of FAIRA (Foundation for Aboriginal and Islanders Research Action), together with Neville Bonner – Australia’s first Aboriginal Senator – proclaimed it ‘Aboriginal land’. Musgrave Park could hardly be more central to the issue of land rights. It lies in inner Brisbane – just across the river from the government agencies that were at the time trying to quash Aboriginal appeals for landownership, yet within the state’s cultural hub, the South Bank Precinct. It was a very contentious green space. Written and oral sources concur that the park had been an Aboriginal networking venue since the 1940s.1 OPAL (One People of Australia League) House – Queensland’s first Aboriginal-focused organisation – was established close to the park in 1961 specifically to service the large number of Aboriginal people already using it. Soon after, many key Brisbane Aboriginal services sprang up around the park’s peripheries. By 1971, the Black Panther party emerged with a dramatic march into central Brisbane.2 More recently, Musgrave Park served as Queensland’s ‘tent 1 Aird 2001; Romano 2008. 2 Lothian 2007: 21. 141 ABORIGINAL HISTORY VOL 42 2018 embassy’ and tent city for a series of protests (1988, 2012 and 2014).3 It attracts 20,000 people to its annual NAIDOC (National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee) Week, Australia’s largest-attended NAIDOC venue.4 This history makes Musgrave Park the unofficial political capital of Aboriginal Brisbane. -

EMERGENCY SERVICES - STAYING SAFE Organisation Contact Details About This Organisation Website Life Threatening Emergencies

EMERGENCY SERVICES - STAYING SAFE Organisation Contact details About this organisation Website Life Threatening Emergencies. For life EMERGENCY Telephone Triple Zero http://www.disaster.qld.gov.au/Disaster- threatening, critical or serious situations EMERGENCY Organisations Police, Ambulance, Fire Brigade (000) Resources/Emergency_Contacts.html only Queensland Police Services is the states law enforcement agency. This site provides and overview of the service, community programs (Youth/PCYC, alcohol and drug, community liaison and support, road EMERGENCY Telephone Triple Zero POLICE safety FAQs, Crime Victims survey, Community Supporting Police, Neighbourhood watch, safer Qld http://www.police.qld.gov.au/forms/contact.asp (000) Community Grants, Weapons Licensing), Regional Policing information and on-line services. The Police Service have police liaison officers that speak various languages. CRIME STOPPERS 1800 333 000 For urgent matters http://www.police.qld.gov.au/ POLICELINK 131 444 For non-urgent contact. 24/7 reporting of non-urgent incidents and non-urgent property crime http://www.police.qld.gov.au/ Police Liaison Officers are employed by the Queensland Police Service to establish and maintain a Cultural Advisory Unit 07 3364 positive rapport between culturally specify communities and the Queensland Police Service. The PLO POLICE LIAISON OFFICER 3934 or contact your local police positions are filled by people from CALD backgrounds including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, http://www.police.qld.gov.au/join/plo/default.htm station Chinese, Vietnamese, Fijian-Indian, Samoan, Sudanese and Arabic speaking backgrounds. PLOs role is to build trust and understanding through liaison by assisting community and police reduce and prevent POLICE STATION LOCATOR QPS General Enquiries - 131 444 Use the website tool to find the nearest Police Station to a Queensland location. -

Brisbane North Report

Brisbane North Area Report 125 YEARS OF OPPORTUNITY The Peet Group offers an impressive breadth of experience in residential, medium density and commercial developments, as well as land syndication and fund management. The core of our success, and our confdence in the future, extends from the commitment, spirit and passion of founder, James Thomas Peet, who established Peet in 1895. James Peet created the opportunity for every person of every kind to create a bright future for themselves and their families. He created Peet communities - a range of exceptional places across Australia. This vision and dedication has grown to over 50 communities nationally. Our commitment to excellence drives our innovation and market-leading practices, backed by 125 years of experience and expertise. That’s the Peet difference. Current communities in South East Queensland include: - Riverbank, Caboolture South - Eden’s Crossing, Redbank Plains - Village Green, Palmview - Spring Mountain, Greenbank - Flagstone SALES INFORMATION: Luke Fraser I 0499 977 759 I [email protected] Disclaimer: Images in this report are for illustrative purposes only. This report and the information it contains is for marketing purposes only and does not provide any guarantees about property decisions or predictions about investment outcomes. This information is not to be taken as providing fnancial or legal advice. It is recommended that before making any decisions you seek independent fnancial and legal advice. It is noted that Australia has a complex legal and property system and that any decision you make should be in conjunction with your personal fnancial and legal advisers. The information included in this report is to give you a general impression of the area only at the time of publication. -

Revised List of Queensland Birds

Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement 0 19. 1984 Revised List ofQueensland Birds G.M.Storr ,~ , , ' > " Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement No. 19 I $ I,, 1 > Revised List oflQueensland Birds G. M. Storr ,: i, Perth 1984 'j t ,~. i, .', World List Abbreviation: . Rec. West. Aust. Mus. Suppl. no. 19 Cover Palm Cockatoo (Probosciger aterrimus), drawn by Jill Hollis. © Western Australian Museum 1984 I ISBN 0 7244 8765 4 Printed and Published by the Western Australian Museum, j Francis Street, Perth 6000, Western Australia. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction. ...................................... 5 List of birds. ...................................... 7 Gazetteer ....................................... .. 179 3 INTRODUCTION In 1967 I began to search the literature for information on Queensland birds their distribution, ecological status, relative abundance, habitat preferences, breeding season, movements and taxonomy. In addition much unpublished information was received from Mrs H.B. Gill, Messrs J.R. Ford, S.A. Parker, R.L. Pink, R.K. Carruthers, L. Neilsen, D. Howe, C.A.C. Cameron, Bro. Matthew Heron, Dr D.L. Serventy and the late W.E. Alexander. These data formed the basis of the List of Queensland birds (Stort 1973, Spec. Pubis West. Aust. Mus. No. 5). During the last decade the increase in our knowledge of Queensland birds has been such as to warrant a re-writing of the List. Much of this progress has been due to three things: (1) survey work by J.R. Ford, A. Gieensmith and N.C.H. Reid in central Queensland and southern Cape York Peninsula (Ford et al. 1981, Sunbird 11: 58-70), (2) research into the higher categories ofclassification, especially C.G. -

Msx Resulsts 2014

MSX RESULSTS 2014 PLATINUM QBR Barbarian Swim Club Leanne Burton QMY Manly Brisbane Angus Macleod QMY Manly Brisbane Todd Robinson QUQ University of Qld Brett Woods QBN Brisbane Northside Tracy Clarkson QWY Whitsunday Warriors Mark Erickson QLT Long Tan Legends Michelle Scott QRC River City John Tweedy QUQ University of Qld Scott Winter QPN Redcliffe Peninsula Jake Lippiatt QSM Brisbane Southside Jen Thomasson QAC Albany Creek Jamie Wright QLT Long Tan Legends Dale Eriksen QLT Long Tan Legends Ahlanna Hayes QNA Noosa Masters Stephanie Jones QNA Noosa Masters Wendy Twidale QGC Gold Coast Cathryn Rayward QRT Rats of Tobruk Lee Zahner QMM Miami Masters Liala Davighi QGS Gladstone Gropers Mark Que QRC River City Alexandra Beitzel QMM Miami Masters Henry Vagner QRC River City Nicolai Morris QLT Long Tan Legends John McKaig QUQ University of Qld Mark Hickman QSE Cairns Sea Eagles Karen Candler QYP Yeronga Yabbies Russell Henry QAC Albany Creek Rachael Keogh QSE Cairns Sea Eagles Karen Harvey QLT Long Tan Legends William Hall QBR Barbarian Swim Club Jackie Goldston QRT Rats of Tobruk Kevin Jackson QRC River City Kylie Fletcher QTT Twin Towns George Corones QGS Gladstone Gropers Richard Furness QGC Gold Coast Leanne Hastings MSX RESULSTS 2014 QMM Miami Masters David Boylson QRC River City Stacia Riddle QUQ University of Qld Martin Banks QMM Miami Masters Alan Carlisle QCN Cairns Mudcrabs Osamu Sakamoto QRC River City Brett Fischer QAC Albany Creek Peter Mulcahy QMM Miami Masters Denise Robertson QRC River City Phil Wheeler QMY Manly Brisbane -

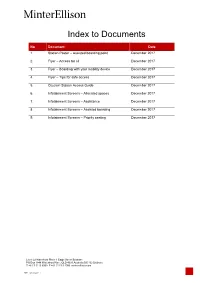

Index to Documents

Index to Documents No Document Date 1. Station Poster – Assisted boarding point December 2017 2. Flyer – Access for all December 2017 3. Flyer – Boarding with your mobility device December 2017 4. Flyer – Tips for safe access December 2017 5. Citytrain Station Access Guide December 2017 6. Infotainment Screens – Allocated spaces December 2017 7. Infotainment Screens – Assistance December 2017 8. Infotainment Screens – Assisted boarding December 2017 9. Infotainment Screens – Priority seating December 2017 Level 22 Waterfront Place 1 Eagle Street Brisbane PO Box 7844 Waterfront Place QLD 4001 Australia DX 102 Brisbane T +61 7 3119 6000 F +61 7 3119 1000 minterellison.com ME_143266442_1 Do you require assistance getting on or off the train? Please wait near the assisted boarding point and we will come to you. How it works • Boarding assistance may be provided by station staff present on the platform. • Alternatively, assistance will be provided by the train guard at the assisted boarding point. For further information Use the station help phone, the onboard emergency help button, text 0428 774 636 or call 13 16 17 Access for all If you need assistance getting on or off the train at any Citytrain station, just wait near the assisted boarding point and we will come to you. This point is indicated by a blue and white symbol for accessibility and is typically located near the middle of the platform. At many stations, the assisted boarding point will be located on a higher section of the platform to allow for easier access to and from the carriage. The assisted boarding point is also usually close to other access features such as the emergency and disability assistance phone, hearing aid loops, audio and visual timetable information and lifts. -

North Coast Road Facts 2010-11

North Coast Road Facts 2010-11 Maroochy River Bridge Area profile Area: 10 620km2, extending along the coast from Noosa to Redcliffe, and from Caboolture to west of Esk. Population: Around 666 618. Industries: Tourism, agriculture, forestry, fishing, dairying, retail. Connecting Queensland Transport and Main Roads www.tmr.qld.gov.au North Coast Road Facts Connecting North Coast Transport and Main Roads services the state-controlled road network in Queensland. The department’s Queensland Transport and Roads Investment Program 2010-11 to 2013-14, outlines what the department is doing in the North Coast Region of Queensland, now and in the future. The department’s Sunshine Coast Office and Moreton Office are the main points of contact for residents, industry and business to connect with Transport and Main Roads and learn more about what is happening in the area. State road projects in the North Coast Region are funded by the Queensland Government and the Federal Government. In the current roads program, the Queensland Government is investing around $221 million in the region (including over $4.5 million in Transport Infrastructure Development Scheme projects), and the Federal Government is contributing over $40.7 million. Developers also contribute to the roads program. Road network • Bruce Highway • Emu Mountain Road • Maleny - Stanley River Road (Brisbane - Gympie) • Cooroy Connection Road • Landsborough - Maleny Road • Warrego Highway • Sunshine Motorway • Maleny - Kenilworth Road (Ipswich - Toowoomba) (Tanawha - Peregian) • Nambour - Mapleton Road • D’Aguilar Highway • Caloundra-Mooloolaba Road (Caboolture - Yarraman) • Maleny - Montville Road • Kawana Way • Brisbane Valley Highway • Woombye - Montville Road (Ipswich - Harlin) • Nicklin Way • Montville - Mapleton Road • Redcliffe Road • Brisbane - Woodford Road • Everton Park - Albany Creek Road • Deception Bay Road • Samford - Mt. -

South East Queensland Train Network Map Effective 4 October 2016

South East Queensland train network map Effective 4 October 2016 Gympie North Sunshine Coast line Key Traveston Cooran Ferny Grove and Beenleigh lines Pomona North Cooroy Eumundi Nambour– Shorncliffe and Cleveland lines Yandina Caboolture Nambour railbus Airport and Gold Coast lines Woombye Palmwoods Caboolture/Sunshine Coast Eudlo and Ipswich/Rosewood lines Mooloolah Redcliffe Peninsula and Springfield lines Landsborough Australia Zoo Beerwah Doomben line Glasshouse Mountains Beerburrum Special event service only Elimbah Route 649: Nambour–Caboolture railbus Caboolture line Caboolture Redcliffe Peninsula line Morayfield Kippa-Ring Rothwell Burpengary Mango Hill East Transfer to other train services Narangba Mango Hill Murrumba Downs Dakabin Transfer to busway services Kallangur Petrie Special fares apply Lawnton Bray Park Wheelchair access Strathpine Shorncliffe line Assisted wheelchair access Bald Hills Carseldine Shorncliffe Ferny Grove line Zillmere Sandgate This map only shows connecting railbus services at Ferny Grove Deagon Geebung train stations. These railbus services replace train Keperra North Boondall services. Many more bus services are scheduled to Grovely Sunshine Boondall Oxford Park Nudgee connect with train services at most train stations. Virginia Mitchelton Banyo Gaythorne Express services do not stop at all stations depicted Bindha Enoggera on this map. Please refer to separate line timetables Northgate Alderley Nundah for details. Newmarket Toombul AirportAirport (International) (Domestic) Wilston Airport line Most train stations have free park’n’ride facilities. Windsor Clayfield Eagle Junction Hendra Exhibition Wooloowin For details visit translink.com.au or call Albion Ascot 13 12 30 anytime. Roma Doomben Street Doomben # Services to and from the airport stations Bowen Hills line Milton are operated by Airtrain Citylink Limited Fortitude Valley ABN 98 066 543 315 pursuant to a contract Auchenflower Brisbane Central for services with Queensland Rail.