Eulemur Mongoz): Evidence from a Search Task

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Human Disturbance on the Mongoose Lemur Eulemur Mongoz in Comoros: Implications and Potential for the Conservation of a Critically Endangered Species

Effects of human disturbance on the mongoose lemur Eulemur mongoz in Comoros: implications and potential for the conservation of a Critically Endangered species B AKRI N ADHUROU,ROBERTA R IGHINI,MARCO G AMBA,PAOLA L AIOLO A HMED O ULEDI and C RISTINA G IACOMA Abstract The decline of the mongoose lemur Eulemur mon- conversion of forests into farmland, habitat loss and frag- goz has resulted in a change of its conservation status from mentation, hunting for meat, and direct persecution as agri- Vulnerable to Critically Endangered. Assessing the current cultural pests (Schwitzer et al., ). Shortage of essential threats to the species and the attitudes of the people coexist- resources, poverty and food insecurity often accentuate an- ing with it is fundamental to understanding whether and thropogenic pressures. Human well-being is dependent on how human impacts may affect populations. A question- biodiversity (Naeem et al., ) but many activities deemed naire-based analysis was used to study the impact of agricul- indispensable for human subsistence lead to biodiversity ture and other subsistence activities, and local educational losses (Díaz et al., ; Reuter et al., ). Damage to initiatives, on lemur abundance, group size and compos- crops, livestock or human life by wildlife provides sufficient ition in the Comoros. On the islands of Mohéli and motivation for people to eradicate potential animal compe- Anjouan we recorded lemurs in groups, the size titors (Ogada et al., ) and to reduce the quantity and and composition of which depended both on environmental quality of natural habitats on private and communal lands parameters and the magnitude and type of anthropogenic (Albers & Ferraro, ). -

Inspection Report

United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 2562 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 08-SEP-14 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 2562 33-C-0001 001 PEORIA PARK DISTRICT 08-SEP-14 Count Species 000001 Cattle/cow/ox/watusi 000003 Red-necked wallaby 000002 Slender-tailed meerkat 000004 Cotton-top tamarin 000003 Mandrill *Male 000002 Grevys zebra 000001 Gerenuk 000002 Reeve's muntjac 000001 European polecat 000001 Kinkajou 000002 Black-and-rufous elephant shrew 000001 Maned wolf 000003 Black-handed spider monkey 000003 Thomsons gazelle 000001 Prehensile-tailed porcupine 000021 Common mole-rat 000003 Cape Porcupine 000002 Takin 000004 Southern three-banded armadillo 000002 Lion 000001 California sealion 000004 Eastern black and white colobus 000002 African wild ass 000005 Tiger 000004 Goat 000002 Mongoose lemur 000003 Red River Hog 000002 White rhinoceros 000002 Hoffmanns two-toed sloth 000001 Sugar glider 000002 Giraffe 000003 Parma wallaby 000022 Greater spear-nosed bat 000001 Llama 000002 Chinchilla 000002 Ring-tailed lemur 000005 European rabbit 000125 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 2562 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 12-NOV-15 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 2562 33-C-0001 001 PEORIA PARK DISTRICT 12-NOV-15 Count Species 000001 Northern tree shrew 000001 Cattle/cow/ox/watusi 000003 Red-necked wallaby 000005 Slender-tailed meerkat 000004 Cotton-top tamarin 000002 Mandrill -

Large Lemurs: Ecological, Demographic and Environmental Risk Factors for Weight Gain in Captivity

animals Article Large Lemurs: Ecological, Demographic and Environmental Risk Factors for Weight Gain in Captivity Emma L. Mellor 1,* , Innes C. Cuthill 2, Christoph Schwitzer 3, Georgia J. Mason 4 and Michael Mendl 1 1 Bristol Veterinary School, University of Bristol, Langford House, Langford, Bristol BS40 5DU, UK; [email protected] 2 School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Life Sciences Building, 24 Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TQ, UK; [email protected] 3 Dublin Zoo, Phoenix Park, Dublin 8, D08 WF88, Ireland; [email protected] 4 Department of Animal Biosciences, University of Guelph, 50 Stone Road East, Guelph, ON N1G 2W1, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 12 August 2020; Published: 18 August 2020 Simple Summary: Excessive body mass, i.e., being overweight or obese, is a health concern. Some lemur species are prone to extreme weight gain in captivity, yet for others a healthy body condition is typical. The first aim of our study was to examine possible ecological explanations for these species’ differences in susceptibility to captive weight gain across 13 lemur species. Our second aim was to explore demographic and environmental risk factors across individuals from the four best-sampled species. We found a potential ecological explanation for susceptibility to captive weight gain: being adapted to unpredictable wild food resources. Additionally, we also revealed one environmental and four demographic risk factors, e.g., increasing age and, for males, being housed with only fixed climbing structures. Our results indicate targeted practical ways to help address weight issues in affected animals, e.g., by highlighting at-risk species for whom extra care should be taken when designing diets; and by providing a mixture of flexible and fixed climbing structures within enclosures. -

(Eulemur Mongoz) at the Lemur Conservation Foundation, Myakka City, Florida

1 Exploring the Impacts of Temperature on the Activity Patterns of Mongoose Lemurs (Eulemur mongoz) at the Lemur Conservation Foundation, Myakka City, Florida _________________________ An Honors Thesis Presented to The Independently Designed Major Program The Colorado College _________________________ by Rebecca Twinney May 2017 Approved: ____________________________Krista Fish Date: ________________________________ 04/19/2017 2 Abstract This study focused on the activity patterns of a male-female pair of semi-free ranging mongoose lemurs (Eulemur mongoz) in Myakka City, Florida. Despite hypotheses that a change in temperature drives the seasonal shift in the species’ activity patterns, previous research has been unable to conclusively isolate this variable. Because the semi-free ranging environment at the Lemur Conservation Foundation provided a constant food source and limited predation, it enabled this study to isolate the effect of temperature. The data illustrated no significant difference between hourly activity levels during sampling periods in the summer and fall of 2016 (P = 0.32). Despite lower temperatures in the fall (P = 0.01), the lemurs’ activity patterns did not significantly alter from those in the warmer summer months. These findings indicate that seasonal food availability, rather than temperature, drives the shifting activity patterns of wild mongoose lemurs. While Curtis et al. (1999) originally suggest that the lemurs’ higher fiber intake during the dry season drives this change in activity, more research is needed in order to fully understand this relationship. INTRODUCTION Thermoregulation In subtropical environments with temperatures that fluctuate with the season, most endothermic animals must rely on behavioral mechanisms of thermoregulation (Donati et al., 2011). In order to maintain homeostasis, species may conduct thermogenesis, the production of body heat, or thermolysis, the dissipation of body heat (Terrien et al., 2011). -

Mongoose Lemur Mammal Eulemer Mongoz

Mongoose Lemur Mammal Eulemer mongoz Scientific Name: Eulemer mongoz Other Names: None Range: Northwestern Madagascar and the Comoro Islands of Moheli and Anjouan Habitat: Primary and secondary dry forests and scrub brush Average Size: Length: Body: 14 in. Tail: 19 in. Photo: Tana Aubert Weight: 2.8 - 3.5 lbs. Conservation The Ankarafantsika Reserve is the only protected area in Madagascar for Description: the mongoose lemur. It is under heavy pressure due to forest clearance Male: Darker than females with gray-brown for pasture, charcoal production and croplands. The exact limits of the fur and rust-colored cheeks and beard mongoose lemur’s distribution in other areas of Madagascar are unknown Female: Gray blending into brown on the due to the forests in the region being highly fragmented. This species is back and rear. Face is dark gray with white protected both by law and local customs on the Comoro Islands where cheeks and beard they were introduced roughly 200 years ago. The influx of Malagasy people (coming from mainland Madagascar) who have different customs than the Lifespan: local Comoro tribes, has led to an increase in the hunting of these lemurs In captivity: 30 years for food. The wild population is estimated to be between 1,000 and 10,000. There have only been a few good population studies completed. In the wild: Unknown Behavior Diet: This Malagasy species tends to live in small groups of three to four In the wild: Fruit, new leaves, nectar consisting of a mature pair and its immature offspring. Larger groups are (especially from the kapok tree) found on the Comoro Islands, suggesting that the typical small group sizes In the zoo: Fruit, vegetables, monkey chow and pair-bonding are influenced by food availability and climatic changes. -

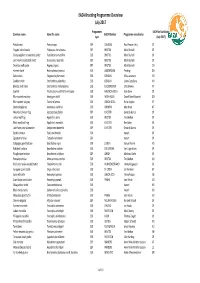

EAZA Breeding Programme Overview July 2017

EAZA Breeding Programme Overview July 2017 Programme IUCN Red List Status Common name Scientific name EAZA Member Programme coordinator type (July 2017) Partula snail Partula sspp. EEP LONDON Paul Pearce‐Kelly CR Fregate Island beetle Polposipus herculeanus EEP BRISTOL Mark Bushell CR Gooty sapphire ornamental spider Poecilotheria metallica ESB BRISTOL Mark Bushell CR Lord Howe Island stick insect Dryococelus australis EEP BRISTOL Mark Bushell CR Desertas wolf spider Hognas ingens EEP BRISTOL Mark Bushell DD Horned shark Heterodontus francisci ESB AMSTERDAM Pending DD Zebra shark Stegostoma fasciatum ESB GENOVA Silvia Lavorano VU Sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus ESB GENOVA Laura Castellano VU Blacktip reef shark Carcharhinus melanopterus ESB CHESSINGTON Chris Brown NT Sawfish Pristis zijsron and Pristin microdon ESB VALENCIA‐OCEA Kate Duke CR Blue spotted maskray Neotrygon kuhlii ESB WIEN‐AQUA Daniel Abed‐Navandi DD Blue spotted stingray Taeniura lymma ESB LISBOA‐OCEA Nuria Baylina NT Spotted eagle ray Aetobatus ocellatus ESB ARNHEM Max Janse NT Mountain chicken frog Leptodactylus fallax EEP CHESTER Gerardo Garcia CR Lemur leaf frog Agalychnis lemur ESB BRISTOL Tim Skelton CR Black‐eyed leaf frog Agalychnis moreletii ESB CHESTER Ben Baker CR Lake Patzcuaro salamander Ambystoma dumerilii EEP CHESTER Gerardo Garcia CR Spider tortoise Pyxis arachnoides ESB Vacant CR Egyptian tortoise Testudo kleinmanni EEP Vacant CR Galapagos giant tortoise Geochelone nigra ESB ZURICH Samuel Furrer VU Radiated tortoise Geochelone radiata ESB ESKILSTUNA -

2016 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD PRESIDENT In 2017, we will proudly mark the Sacramento Zoo’s 90th birthday. This year, the Sacramento Zoological Society took a number of steps to ensure the celebration will be truly memorable. In conjunction with the Zoo’s Executive Director/ CEO Kyle Burks, the Board of Trustees launched a change initiative designed to chart the course for the next 10 to 20 years at the Sacramento Zoo. It’s an initiative appropriate for one of Sacramento’s top visitor attractions. Yes, with more than a half million visitors annually, the Zoo is truly the region’s family destination. We’re gearing up and exciting change is all around us at the Zoo. Certainly, everyone loves the newest members of our animal family, including four Red River Hoglets, a pair of Eastern Bongo, and Rocket, our young Masai Giraffe. Our lion cubs aren’t so little anymore, but they still draw crowds. MISSION STATEMENT You’ll see the Zoo’s lush setting has become more beautiful with increased attention to the grounds, new fencing around the lake and better screening of maintenance areas. And The Sacramento Zoo inspires appreciation, respect and a connection we are getting close to finalizing plans for a state-of-the-art with wildlife and nature through project to replace our outdated Reptile House with a modern, education, recreation and conservation. much more animal-friendly and visitor-welcoming Biodiversity Center. 2016 BOARD OF TRUSTEES In 2016, Trustees made two other major investments in our future. We formally launched a master planning project that Jeff Raimundo Fran Boland will guide growth and renewal of the Zoo over the next 20 President Michael Broughton Elizabeth Stallard Nancy E. -

December 2013

E-ulemur Latitudes e-newsletter December 2013 www.lemurreserve.org Click here to peek inside the Ako books and receive our special watercolor by Deborah Ross holiday offer for the six book deborahrossart.com series. Thank You For Your Involvement & Support We have had a very successful and exciting year at the Lemur Conservation Foundation (LCF) with some significant achievements in our conservation, education, and outreach partnerships. Thanks to your involvement, we are able to increase our impact in the communities we serve, as well as meet the challenges facing lemurs, the most endangered primates species in the world, and Madagascar's important biodiversity. At this time we invite you to join us as we build on our successes. For example, in 2012 all three of the rare Mongoose lemurs born in the United States belonged to LCF. In addition to the Mongoose lemur births, Ansell, a Ring-tailed lemur, gave birth to twins. Ansell is an experienced mother, who gave birth in the forest for the second time and reared her infants while leading her troop, marking a significant achievement for our free- ranging colony. Find organic spices from Madagascar in our Amazon store This is why we ask you to consider a year-end gift to help us expand our success in lemur propagation, the core of our mission, onsite research opportunities, and education outreach that will help build awareness about lemurs and sustain their populations in the future. In 2014 LCF's Ako Project, a series of six books for children 4 to 8 years old, written by Dr. -

The Endangered Species Challenge

The Endangered Species Challenge: Making Use of Opportunistic Sampling Erin Ehmke, PhD – Research Manager Sarah Zehr, PhD – Data Manager The DLC Colony • The world’s largest living colony of endangered primates • Currently, 22 species, 11 genera and nearly 250 individual strepsirrhine primates • No other primate center or zoo maintains a similar diversity of prosimians; smaller colonies elsewhere are largely or entirely unavailable for research. • In the wild, the 80+ species of lemurs are endemic only to Madagascar • All lemur species are protected by CITES Appendix I regulations and the Endangered Species Act • It would be impossible to duplicate the diversity of the DLC colony today. • 48 year history long-term data on known individuals with known pedigrees The Duke Lemur Center conservation research education hey. a squirrel. Research at the DLC # in research Species (2013) current colony C. medius (fat-tailed dwarf lemur) 15 19 D. madagascariensis (aye aye) 16 16 E. collaris (collared lemur) 6* 4 E. coronatus (crowned lemur) 11* 10 E. macaco flavifrons (blue-eyed black lemur) 5 14 E. macaco macaco (black lemur) 1 3 E. mongoz (mongoose lemur) 10 11 E. rubriventer (red-bellied lemur) 6 6 E. rufus (red-fronted lemur) 2 2 Eulemur sp. 3 4 H. griseus (grey gentle lemur) 3 3 L. catta (ring-tailed lemur) 40* 37 M. murinus (mouse lemur) 42 48 N. pygmaeus (pygmy slow loris) 1 8 P. coquerli (Coquerel's sifaka) 26 31 Varecia rubra (red ruffed lemur) 19* 15 Varecia variegata (black & white ruffed lemur) 12* 11 TOTAL NUMBER OF ANIMALS1 218 242 -

Lemurs of Madagascar – a Strategy for Their

Cover photo: Diademed sifaka (Propithecus diadema), Critically Endangered. (Photo: Russell A. Mittermeier) Back cover photo: Indri (Indri indri), Critically Endangered. (Photo: Russell A. Mittermeier) Lemurs of Madagascar A Strategy for Their Conservation 2013–2016 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Nicola Davies, Steig Johnson, Jonah Ratsimbazafy, Josia Razafindramanana, Edward E. Louis Jr., and Serge Rajaobelina Illustrations and layout by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation Conservation International This publication was supported by the Conservation International/Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation Primate Action Fund, the Bristol, Clifton and West of England Zoological Society, Houston Zoo, the Institute for the Conservation of Tropical Environments, and Primate Conservation, Inc. Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, and Conservation International Copyright: © 2013 IUCN Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA Citation: Schwitzer C, Mittermeier RA, Davies N, Johnson S, Ratsimbazafy J, Razafindramanana J, Louis Jr. EE, Rajaobelina S (eds). 2013. Lemurs of Madagascar: A Strategy for Their Conservation 2013–2016. Bristol, UK: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, and Conservation International. 185 pp. ISBN: 978-1-934151-62-4 Illustrations: © Stephen D. -

Studbooks in ZSL Library (Updated October 2013)

Studbooks in ZSL Library (Updated October 2013) Common name Scientific name Level Year Issue/Edition Notes Aardvark Orycteropus afer European 1996 1 European 2008 Update to 4th ed. Electronic resource European 2009 2nd update to 4th ed. Electronic resource Addax Addax nasomaculatus European 1992 European 1999 International 1989 International 1994 African and Indian elephant British Isles [1980s] African black-footed penguin Spheniscus demersus North American 1991 African elephant Loxodonta spp. North American Region 2011 Electronic resource African pancake tortoise Malacochersus tornieri European Update 2005 Electronic resource African pengiun Spheniscus demersus European 1993 African penguin British 1993 draft African pygmy falcon Polihierax semitorquatus North American 2000 Common name Scientific name Level Year Issue/Edition Notes African rhinoceros Diceros bicornis / Ceratotherium simum International 1983 2 International 1987 3 International 1991 4 International 1997 7 International 1999 8 African slender-snouted Crocodylus cataphractus crocodile North American 1997 African wild asses Equus africanus International 1976 4 International 1978 6 International 1981 7/8/9 International 1983 10/11 International 1984 12 International 1985 13 International 1986 14 International 1987 15 International 1988 16 International 1989 17 International 1991 19 International 1992 20 International 1993 21 International 1994 22 International 1995 23 Common name Scientific name Level Year Issue/Edition Notes International 1996 24 International 1997 25 International 1998 26 International 1999 27 International 2000 28 International 2001 29 International 2002 30 International 2003 31 International 2004 32 International 2005 33 International 2007 35 International 2008 No. 36 International 2009 No. 37 International 1977 5 African wild dog Lycaon pictus European 2008 10 Electronic resource European 2009 11th ed. -

Annual Report MIARAKA | TOGETHER

2017 LEMUR CONSERVATION FOUNDATION Annual Report MIARAKA | TOGETHER 1 On the cover: A silky sifaka photographed by Dr. Erik Patel in Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve. Pictured on the inside covers are scenic views of Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve (ASSR) and neighboring villages (front) and Marojejy National Park (back) in northeastern Madagascar. The Lemur Conservation Foundation works with partners on the ground to support these mountainous rainforest reserves, and established Camp Indri in ASSR as an ecotourism destination. Spanning 280 sq km (108 square miles), ASSR is home to at least 11 species of lemurs, including critically endangered indri and silky sifakas, and a wide variety of rare plants and wildlife. Photo credit: Dr. Erik Patel 2 Dear Friends OF THE LEMUR you make it possible to protect 830 square Conservation Foundation, miles of pristine lemur habitat as well as create sustainable livelihoods in Madagas- Table of contents The Lemur Conservation Foundation’s car, educate the next generation of con- progress toward our vital mission to save servationists, and expand our conservation the primates of Madagascar from extinc- breeding program at our lemur reserve in Director’S Letter 1 tion is made possible only by the combined Florida. Thank you for partnering with us efforts, compassion, and support of our to create positive change for lemurs, com- Lemurs 2 Malagasy partners, generous donors, dedi- munities, and our planet. cated Board of Directors, expert Scientific reserve 4 Advisory Council, researchers, artists, With gratitude, educators, and committed staff, interns, and volunteers. madagascar 6 Miaraka is the Malagasy word for togeth- er, and together we share and demonstrate Dr.