Large Lemurs: Ecological, Demographic and Environmental Risk Factors for Weight Gain in Captivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

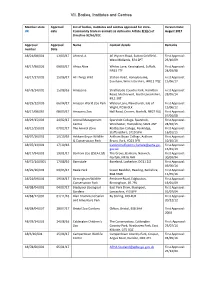

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

In Situ Conservation

NEWSN°17/DECEMBER 2020 Editorial IN SITU CONSERVATION One effect from 2020 is for sure: Uncertainty. Forward planning is largely News from the Little Fireface First, our annual SLOW event was impossible. We are acting and reacting Project, Java, Indonesia celebrated world-wide, including along the current situation caused by the By Prof K.A.I. Nekaris, MA, PhD by project partners Kukang Rescue Covid-19 pandemic. All zoos are struggling Director of the Little Fireface Project Program Sumatra, EAST Vietnam, Love economically after (and still ongoing) Wildlife Thailand, NE India Primate temporary closures and restricted business. The Little Fireface Project team has Investments in development are postponed Centre India, and the Bangladesh Slow at least. Each budget must be reviewed. been busy! Despite COVID we have Loris Project, to name a few. The end In the last newsletter we mentioned not been able to keep up with our wild of the week resulted in a loris virtual to forget about the support of the in situ radio collared slow lorises, including conference, featuring speakers from conservation efforts. Some of these under welcoming many new babies into the the helm of the Prosimian TAG are crucial 11 loris range countries. Over 200 for the survival of species – and for a more family. The ‘cover photo’ you see here people registered, and via Facebook sustainable life for the people involved in is Smol – the daughter of Lupak – and Live, more than 6000 people watched rd some of the poorest countries in the world. is our first 3 generation birth! Having the event. -

Effects of Human Disturbance on the Mongoose Lemur Eulemur Mongoz in Comoros: Implications and Potential for the Conservation of a Critically Endangered Species

Effects of human disturbance on the mongoose lemur Eulemur mongoz in Comoros: implications and potential for the conservation of a Critically Endangered species B AKRI N ADHUROU,ROBERTA R IGHINI,MARCO G AMBA,PAOLA L AIOLO A HMED O ULEDI and C RISTINA G IACOMA Abstract The decline of the mongoose lemur Eulemur mon- conversion of forests into farmland, habitat loss and frag- goz has resulted in a change of its conservation status from mentation, hunting for meat, and direct persecution as agri- Vulnerable to Critically Endangered. Assessing the current cultural pests (Schwitzer et al., ). Shortage of essential threats to the species and the attitudes of the people coexist- resources, poverty and food insecurity often accentuate an- ing with it is fundamental to understanding whether and thropogenic pressures. Human well-being is dependent on how human impacts may affect populations. A question- biodiversity (Naeem et al., ) but many activities deemed naire-based analysis was used to study the impact of agricul- indispensable for human subsistence lead to biodiversity ture and other subsistence activities, and local educational losses (Díaz et al., ; Reuter et al., ). Damage to initiatives, on lemur abundance, group size and compos- crops, livestock or human life by wildlife provides sufficient ition in the Comoros. On the islands of Mohéli and motivation for people to eradicate potential animal compe- Anjouan we recorded lemurs in groups, the size titors (Ogada et al., ) and to reduce the quantity and and composition of which depended both on environmental quality of natural habitats on private and communal lands parameters and the magnitude and type of anthropogenic (Albers & Ferraro, ). -

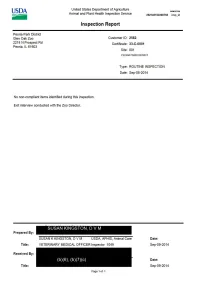

Inspection Report

United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 2562 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 08-SEP-14 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 2562 33-C-0001 001 PEORIA PARK DISTRICT 08-SEP-14 Count Species 000001 Cattle/cow/ox/watusi 000003 Red-necked wallaby 000002 Slender-tailed meerkat 000004 Cotton-top tamarin 000003 Mandrill *Male 000002 Grevys zebra 000001 Gerenuk 000002 Reeve's muntjac 000001 European polecat 000001 Kinkajou 000002 Black-and-rufous elephant shrew 000001 Maned wolf 000003 Black-handed spider monkey 000003 Thomsons gazelle 000001 Prehensile-tailed porcupine 000021 Common mole-rat 000003 Cape Porcupine 000002 Takin 000004 Southern three-banded armadillo 000002 Lion 000001 California sealion 000004 Eastern black and white colobus 000002 African wild ass 000005 Tiger 000004 Goat 000002 Mongoose lemur 000003 Red River Hog 000002 White rhinoceros 000002 Hoffmanns two-toed sloth 000001 Sugar glider 000002 Giraffe 000003 Parma wallaby 000022 Greater spear-nosed bat 000001 Llama 000002 Chinchilla 000002 Ring-tailed lemur 000005 European rabbit 000125 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 2562 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 12-NOV-15 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 2562 33-C-0001 001 PEORIA PARK DISTRICT 12-NOV-15 Count Species 000001 Northern tree shrew 000001 Cattle/cow/ox/watusi 000003 Red-necked wallaby 000005 Slender-tailed meerkat 000004 Cotton-top tamarin 000002 Mandrill -

Subspecific Divergence in the Black Lemur's Low-Pitched Vocalizations

The Open Acoustics Journal, 2008, 1, 49-53 49 Open Access Subspecific Divergence in the Black Lemur’s Low-Pitched Vocalizations M. Gamba* and C. Giacoma Department of Animal and Human Biology, University of Torino, Italy Abstract: Previous studies offered very preliminary information on the vocal repertoire of Eulemur macaco macaco and Eulemur macaco flavifrons. They agreed on the fact that both subspecies emit low-pitched vocalizations, called grunts, of different duration. Through all-occurrence and focal animal observations, we recorded the vocal activity of 31 black le- murs (12 E. m. macaco and 19 E. m. flavifrons) housed in 7 institutions, both in Europe and in Madagascar. We measured both temporal and spectral properties to describe long grunts quantitatively. We extracted acoustic parameters in the per- spective of the source-filter theory of sound production. From spectrograms, we measured call duration and 6 larynx- related features and, using Linear Predictive Coding spectra, we measured four vocal tract related acoustic properties. Our quantitative analysis has statistical support for the classification of long grunts. Using individual mean values and multi- variate Discriminant Function Analysis we have been able to successfully classify 96.8 % of the vocal signals to the sub- species of the emitter. Acoustic cues of both larynx-related and vocal tract-related acoustic parameters offered support for sub-specific recognition potential. However, univariate analyses showed that formants should be providing listeners with subspecies-specific information. INTRODUCTION The existence of an intergradation zone and a geographical cline in subspecific traits between the two forms over the The identification of animal species using acoustic char- Manongarivo Mountain has been suggested [8]. -

& Short Breaks

2018 MAY DATE ADULTS CH/OAP 1st Bridlington or Scarborough £17.50 £16.50 OUR COACHES ARE ALSO 1st Whitby £17.50 £16.50 5th Chester or Chester Zoo (Adm Not Inc) £17.50 £16.50 AVAILABLE FOR PRIVATE HIRE. 6th Whitby £17.50 £16.50 7th Bakewell market, Buxton & meal All Pay £25 7th Skegness £17.50 £16.50 We have everything from 16 to 70 seater Coaches, 7th Bridlington or Scarborough £17.50 £16.50 BREAKS & SHORT SHORT & Standard and Executive! Available for hire for events 8th Yorkshire Coast Tour £17.50 £16.50 such as weddings and special occasions or for organised 9th Bury market & Fish Tea (Wetherby Whaler ) £27.50 £26.50 TRIPS 10th North Wales & Snowdonia Tour £18.50 £17.50 Inc Conwy, Snowdonia Mountains and Betws-Y-Coed groups for holidays or days out. 11th Skipton market & Ilkley £17.50 £16.50 CALL US WITH YOUR 12th York £16.50 £15.50 CALL US TODAY FOR DETAILS. EMAIL ADDRESS TO 13th Whitby £17.50 £16.50 RECEIVE OUR LATEST 16th Southport £17.50 £16.50 19th Liverpool & Albert Dock £17.50 £16.50 DAY OFFERS AND PRICE 20th Bridlington or Scarborough £17.50 £16.50 REDUCTIONS DIRECT 20th Howarth War weekend £17.50 £16.50 TO YOUR INBOX 22nd Kings Lynn famous market £18.50 £17.50 23rd Llandudno £18.50 £17.50 26th City of Oxford £19.00 £18.00 26th Diana ‘Her Fashion Story’ at Kensington Palace All Pay £65 27th Tall Ships of Liverpool All Pay £20 27th Skegness £17.50 £16.50 28th Whitby £17.50 £16.50 28th Chester or Chester Zoo (Adm Not Inc) £17.50 £16.50 29th Bridlington or Scarborough £17.50 £16.50 30th Peak Wildlife Park and Leek £25.00 £24.00 Maxfields Executive Travel Telephone: 0114 287 2622 154 Aughton Road [email protected] www.maxfieldstravel.co.uk Aughton Sheffield S26 3XE www.maxfieldstravel.co.uk JUNE DAY TRIPS TERMS AND CONDITIONS NOVEMBER DECEMBER DATE ADULTS CH/OAP To qualify for CONCESSION rate ALL bus passes MUST be shown. -

Cathemeral Activity Patterns of the Blue-Eyed Black Lemur Eulemur Macaco Flavifrons in Intact and Degraded Forest Fragments

ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Printed October 2007 Vol. 3: 239–247, 2007 Endang Species Res Published online September 12, 2007 Cathemeral activity patterns of the blue-eyed black lemur Eulemur macaco flavifrons in intact and degraded forest fragments Nora Schwitzer1, Werner Kaumanns1, Peter C. Seitz2, Christoph Schwitzer3,* 1Working Group Primatology, Zoologischer Garten Köln, Riehler Strasse 173, 50735 Köln, Germany 2Department of Biophysics, Technische Universität München, James Franck Strasse, 85748 Garching, Germany 3Bristol Zoo Gardens, Clifton, Bristol BS8 3HA, UK ABSTRACT: This study describes the activity pattern of the blue-eyed black lemur Eulemur macaco flavifrons for the first time and investigates the parameters, such as season or habitat, that may influ- ence the distribution of activity over the 24 h cycle. Four groups of E. m. flavifrons in 2 forest frag- ments with different degrees of degradation were followed for 24 h mo–1 over a 7 mo period between July 2004 and July 2005. Blue-eyed black lemurs exhibited a bimodal activity pattern which peaked during the morning and evening twilight. The groups consistently showed activity bouts both during the day and at night, a behaviour that corresponds to Tattersall’s (1987) definition of cathemerality. The proportion of illuminated lunar disc and the nocturnal illumination index were positively associ- ated with the amount of nocturnal activity. Total activity, both diurnal and nocturnal, was signifi- cantly higher in the secondary than in the primary forest. In view of our results, the cathemeral behaviour of E. m. flavifrons may best be explained as flexible responses to a framework of varying environmental factors, each of which may enhance or inhibit activity within the lemurs’ range of adaptability. -

Eulemur Flavifrons) and the Sportive Lemurs (Genus Lepilemur)

Geospatial and genomic tools for conserving the critically endangered blue-eyed black lemur (Eulemur flavifrons) and the sportive lemurs (genus Lepilemur) Jen Tinsman Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2019 Jen Tinsman All rights reserved Abstract Geospatial and genomic tools for conserving the Critically Endangered blue-eyed black lemur (Eulemur flavifrons) and the sportive lemurs (genus Lepilemur) Jen Tinsman Madagascar’s lemurs are the most endangered group of mammals in the world, with 94% of species threatened with extinction. Forest loss is one the greatest threat to these arboreal primates, but hunting, habitat degradation, and climate change also threaten their survival. Lemurs are a diverse group of more than 100 species; and their ecological traits shape how species respond to anthropogenic pressure. Incorporating knowledge of species’ ecological niches and evolutionary histories can contextualize threats and improve conservation assessments. In this dissertation, I investigate what constitutes suitable habitat for lemurs in light of the threats present, their sensitivity to forest fragmentation, their dispersal ability, and their ecological uniqueness. I obtained data about lemur distributions in two ways. First, I conducted field surveys of the Critically Endangered blue-eyed black lemur (Eulemur flavifrons), which only occurs in the ecotone between eastern rainforest and western dry forest in the Sahamalaza region. I also surveyed the range of sister species, the black lemur (E. macaco), which inhabits nearby eastern rainforest in the Manogarivo region. I focused on areas that have not been surveyed recently and on the poorly studied boundary between the species to collect observations from the breadth of these species’ ecological ranges. -

(Eulemur Mongoz) at the Lemur Conservation Foundation, Myakka City, Florida

1 Exploring the Impacts of Temperature on the Activity Patterns of Mongoose Lemurs (Eulemur mongoz) at the Lemur Conservation Foundation, Myakka City, Florida _________________________ An Honors Thesis Presented to The Independently Designed Major Program The Colorado College _________________________ by Rebecca Twinney May 2017 Approved: ____________________________Krista Fish Date: ________________________________ 04/19/2017 2 Abstract This study focused on the activity patterns of a male-female pair of semi-free ranging mongoose lemurs (Eulemur mongoz) in Myakka City, Florida. Despite hypotheses that a change in temperature drives the seasonal shift in the species’ activity patterns, previous research has been unable to conclusively isolate this variable. Because the semi-free ranging environment at the Lemur Conservation Foundation provided a constant food source and limited predation, it enabled this study to isolate the effect of temperature. The data illustrated no significant difference between hourly activity levels during sampling periods in the summer and fall of 2016 (P = 0.32). Despite lower temperatures in the fall (P = 0.01), the lemurs’ activity patterns did not significantly alter from those in the warmer summer months. These findings indicate that seasonal food availability, rather than temperature, drives the shifting activity patterns of wild mongoose lemurs. While Curtis et al. (1999) originally suggest that the lemurs’ higher fiber intake during the dry season drives this change in activity, more research is needed in order to fully understand this relationship. INTRODUCTION Thermoregulation In subtropical environments with temperatures that fluctuate with the season, most endothermic animals must rely on behavioral mechanisms of thermoregulation (Donati et al., 2011). In order to maintain homeostasis, species may conduct thermogenesis, the production of body heat, or thermolysis, the dissipation of body heat (Terrien et al., 2011). -

Biology Workbook 2020

Roding Valley High School A Level Biology Transition booklet Get ready for A-level! A guide to help you get ready for A-level biology, including everything from topic guides to days out and online learning courses. What is included: •Book recommendations •Movie recommendations •Guidance on how to make notes •Research activities – you must complete all of these •Pre-knowledge topics – you must complete all •Ideas for day trips •Science on social media •Science websites https://www.distance-education-academy.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/biology-a-level-course.jpg The compulsory activities highlighted in red must be submitted on google classroom. Please use the code hdkn5x6 to join the classroom and complete any additional work set here. The Light microscope allows you to view animal Prokaryotes are singled celled organisms such as bacteria. cells. It can magnify up to 1500 times. Some organelles such as mitochondria, chloroplasts, Usually much smaller than eukaryotic cells (1/10th the vacuoles, cell walls, cell membranes and nuclei size), do not contain a nucleus, chloroplasts or are visible. Staining makes these organelles mitochondria, DNA can be found floating free in the visible. cytoplasm or in loops called Plasmids, some have flagellum for movement. Label and annotate the diagram Eukaryotic cells are more complex and can be single cellular or multi cellular organisms. The electron microscope; invented in 1950s it allows a much higher magnification (500 000x) and better resolution, allowing greater detail to be seen. Electron microscopes allowed detailed ultrastructure of the cell to be seen, such as ribosomes and the inside of mitochondria and chloroplasts. -

Zooquaria Spring 2020

QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIA SPRINGZ 2020 OO QUARIAISSUE 108 A NOBLE CAUSE SAVING THE DANISH NOBLE CHAFER WHICH FISH? CAMPAIGNING DURING A GLOBAL PANDEMIC 1 BUILDING A FOOD FOREST BEHIND THE SCENES AT A NEW PRIMATE EXHIBIT Elegant enclosures with Webnet The robust wire rope net Webnet enables the realisation of the typically delicate and customized solutions. Jakob Rope Systems supplies both materials and know-how to create functional yet architecturally sophisticated animal enclosures. jakob.com Contents Zooquaria Spring 2020 12 14 4 From the Director’s chair 18 Shifting the population How Covid-19 has affected the EAZA community management paradigm Some insights into the effectiveness of the new 5 From our Chairman RCP process A message of support for EAZA Members 20 A plan for the cinereous vulture 6 Noticeboard An update on the Cinereous vulture EEP Decisions from the latest EAZA Council Meeting 22 Planning for a revolution 7 Just keep swimming How CPSG Europe is ramping up its efforts for An update on our new Which Fish? campaign species conservation 8 Births & hatchings 24 Saving the Danish noble chafer The latest success stories from EAZA zoos Reporting on a new conservation project at Copenhagen Zoo 10 Let’s help nature become part of the solution 26 Taking action for Indonesia Zooquaria talks to Luc Bas, Director of IUCN How threatened ungulates benefited from the first European Regional Office ever Action Indonesia Day 12 A bright future for songbirds 27 Flexible funding for a brighter