The Pearl Incident in Washington D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report 2012

Underground Railroad Educational and Cultural Program Annual Report Model November 30, 2012 Underground Railroad Educational and Cultural Program CFDA 84.345 Project Name: Beneath the Underground and Beyond - The Flight to Freedom and Antebellum Communities in Maryland, 1830 - 1880: Resistance Along the Eastern Shore. Project Number: P345A105002 Project Director’s Name: Chris Haley Project Financial Manager’s Name: Nassir Resvan FY 2011 (October 2011 - September 30, 2012 Annual Report As per the URR Program’s Authorizing Legislation, The Maryland State Archives submits, for this fiscal year in which the organization received URR Program funding this report to the Secretary of Education that contains-- (A) A description of the programs and activities supported by the funding: • Using URR funds, the Maryland State Archives supported the work of its varied stakeholders of researchers, historians, curators and archivists by mining and making electronically accessible all the topics listed below: 1. Federal Census - Mining of the US Federal Census from the years 1830 - 1880 for the counties of Queen Anne, Kent and Dorchester Counties for all entries pertaining to free and enslaved Blacks - Census record mining involves the extraction of biographical data such as name, sex, age, race designation (Black or Mulatto), County District or Precinct, occupation, personal and real estate value and household status and entering that information into a searchable online database. Such information provides invaluable data for family historians, genealogists, scholars and historians whose research and subsequent products involve African American life during Maryland's 19th century before and after the Civil War. Due to funding from this grant, the Archives has been able to accumulate the following totals for the aforementioned counties: Federal Census Entries Year Queen Anne Kent Dorchester Total: 1830/1840 1,762 3,251 5,013 1850/1860 3 5,601 8,711 8,714 1870/1880 2,118 3,861 2,231 8,210 Total: 2,121 11,224 14,193 27,538 2. -

The Pearl Incident Packet

Handout 2 Student Name: _____________________________________ Date: ____________ Teacher:___________________________________________ Class Period: ____ The Pearl Incident Source Packet Document A Source: Excerpted from Daniel Drayton’s “Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton: For four years and four months a prisoner (for charity’s sake) in Washington jail” (1855). Retrieved from Library of Congress. Headnote: Daniel Drayton was the commander of the schooler The Pearl. He was an oyster fisherman who did not own this boat. He paid to borrow it from another man, name unknown, to complete the mission. It is said that Drayton had completed a mission to free enslaved people before, but demanded more and more payment for that mission. He was paid $100 dollars (a large sum for the time) to complete this mission. “Passing along the street, I met Captain Sayres, and knowing that he was sailing a small bay-craft, called The Pearl, and learning from him that business was dull with him, I proposed the enterprise to him...Captain Sayres engaged in this enterprise merely as a matter of business. I, too, was to be paid for my time and trouble,—an offer which the low state of my pecuniary (financial) affairs, and the necessity of supporting my family, did not allow me to decline. But this was not, by any means, my sole or principal motive. I undertook it out of sympathy for the enslaved, and from my desire to do something to further the cause of universal liberty. Such being the different ground upon which Sayres and myself stood, I did not think it necessary -

Final Report 2011

Underground Railroad Educational and Cultural Program Annual Report Model November 30, 2012 Underground Railroad Educational and Cultural Program CFDA 84.345 Project Name: Beneath the Underground and Beyond - The Flight to Freedom and Antebellum Communities in Maryland, 1830 - 1880: Resistance Along the Eastern Shore. Project Number: P345A105002 Project Director’s Name: Chris Haley Project Financial Manager’s Name: Nassir Resvan FY 2011 (October 2010 - September 30, 2011 Annual Report As per the URR Program’s Authorizing Legislation, The Maryland State Archives submits, for this fiscal year in which the organization received URR Program funding this report to the Secretary of Education that contains-- (A) A description of the programs and activities supported by the funding: • Using URR funds, the Maryland State Archives supported the work of its varied stakeholders of researchers, historians, curators and archivists by mining and making electronically accessible all the topics listed below: 1. Federal Census - Federal Census from the years 1830 - 1880 for the counties of Caroline, Queen Anne and Dorchester County for all entries pertaining to free and enslaved Blacks - Census record mining involves the extraction of biographical data such as name, sex, age, race designation (Black or Mulatto), County District or Precinct, occupation, personal and real estate value and household status and entering that information into a searchable online database. Such information provides invaluable data for family historians, genealogists, scholars and historians whose research and subsequent products involve African American life during Maryland's 19th century before and after the Civil War. Due to funding from this grant, the Archives has been able to accumulate the following totals for the aforementioned counties: Federal Census Entries Year Caroline Queen Anne Dorchester Total 1830/1840 1,282 1,045 1,592 3,919 1850/1860 5,583 6,626 3,914 16,123 1870/1880 7,900 1 13,667 21,568 Total: 14,765 7,672 19,173 41,610 2. -

Image Munitions and the Continuation of War and Politics by Other Means

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Image warfare in the war on terror: Image munitions and the continuation of war and politics by other means. Roger, Nathan Philip How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Roger, Nathan Philip (2010) Image warfare in the war on terror: Image munitions and the continuation of war and politics by other means.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42350 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Image warfare in the war on terror: Image munitions and the continuation of war and politics by other means Nathan Philip Roger Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Swansea University 2010 ProQuest Number: 10798058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Chapter Eight “A Strong but Judicious Enemy to Slavery”: Congressman Lincoln (1847-1849) Lincoln's Entire Public Service O

Chapter Eight “A Strong but Judicious Enemy to Slavery”: Congressman Lincoln (1847-1849) Lincoln’s entire public service on the national level before his election as president was a single term in the U. S. House. Though he had little chance to distinguish himself there, his experience proved a useful education in dealing with Congress and patronage. WASHINGTON, D.C. Arriving in Washington on December 2, 1847, the Lincolns found themselves in a “dark, narrow, unsightly” train depot, a building “literally buried in and surrounded with mud and filth of the most offensive kind.”1 A British traveler said he could scarcely imagine a “more miserable station.”2 Emerging from this “mere shed, of slight construction, designed for temporary use” which was considered “a disgrace” to the railroad company as well as “the city that tolerates it,”3 they beheld an “an ill-contrived, 1 Saturday Evening News (Washington), 14 August 1847. 2 Alexander MacKay, The Western World, or, Travels in the United States in 1846-47 (3 vols.; London: Richard Bentley, 1850), 1:162. 3 Letter by “Mercer,” n.d., Washington National Intelligencer, 16 November 1846. The author of this letter thought that the station was “in every respect bad: it is cramped in space, unsightly in appearance, inconvenient in its position, and ill adapted to minister to the comfort of travellers in the entire character of its arrangements.” Cf. Wilhelmus Bogart Bryan, A History of the National Capital from Its Foundation through the Period of the Adoption of the Organic Act (2 vols.; New York: Macmillan, 1914-16), 2:357. -

Death in Wartime: Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 1-1-2005 Death in Wartime: Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan Barbie Zelizer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Zelizer, B. (2005). Death in Wartime: Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 10 (3), 26-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X05278370 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/68 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Death in Wartime: Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan Abstract This article addresses the formulaic dependence of the news media on images of people facing impending death. Considering one example of this depiction — U.S. journalism's photographic coverage of the killing of the Taliban by the Northern Alliance during the war on Afghanistan, the article traces its strategic appearance and recycling across the U.S. news media and shows how the beatings and deaths of the Taliban were depicted in ways that fell short of journalism's proclaimed objective of fully documenting the events of the war. The article argues that in so doing, U.S. journalism failed to raise certain questions about the nature of the alliance between the United States and its allies on Afghanistan's northern front. Disciplines Journalism Studies This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/68 Death in Wartime Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan Barbie Zelizer This article addresses the formulaic dependence of the news media on images of people facing impending death. -

Light Green Mountain Travel Agency Sales Trifold Brochure

REMEMBER COMMEMORATING THE HISTORIC ESCAPE TO Pearl as Metaphor THE PEARL FREEDOM FROM "The Pearl was the name of the vessel on which 77 African Americans sought to SLAVERY escape from enslavement in Washington DC. Thinking of what a pearl is and how it is made can serve as a metaphor to help us become conscious of the historical importance and contemporary significance APRIL 15, 7PM of that courageous act in 1848. It can also AN ONLINE EVENT be a basis for understanding the story of African Americans in Washington and the FEATURING: nation—a hidden history now coming to DC HISTORIAN C.R. GIBBS light." & DAWNE YOUNG, Dr. Sheila S. Walker, Cultural Anthropologist EDMONSON DESCENDANT P We are a group of SW community members invited by Vyllorya Evans and Rev. Ruth Hamilton of TINYURL.COM/PEARLSW U Westminster Presbyterian Church to renew interest O in the story of "The Pearl" and its powerful meaning R for today. We honor the long-standing work of The G Pearl Coalition led by Mr. David Smith, grandson of L founder Mr. Lloyd Smith. Group participants have R included: Audrey Hinton, Vania Georgieva, Dr. Sheila APRIL 15-18 A S. Walker, Georgine Wallace, Kenneth Ward, and E Chris Williams. APRIL 15, VISIT MEMORIAL SITE AT P Special thanks for this year's Commemorative Event to: Jonathan Holley, soloist; Lavonda Broadnax and E SW DUCK POND Marcia Cole, Female Re-Enactors of Distinction; and H Lexie Albe and Jessie Himmelrich, SW BID. T 1848 FLOWERS ENCOURAGED UNDERGROUND RAILROAD THE PEARL ESCAPE OF 1848 SIGN AL Those using the Underground This courageous bid for freedom by 77 men, Finally, by Sunday evening, they came to the Railroad utilized the local pla nts women, and children was one of the many broad Chesapeake where freedom must have for nourishment and even attempted escapes by enslaved African seemed so close. -

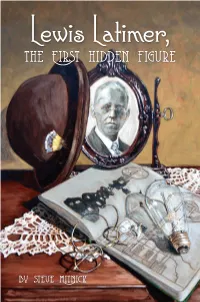

Lewis Latimer, the First Hidden Figure

Lewis Latimer, the First hidden figure by steve Mitnick Lewis Latimer, the First hidden figure Also by Steve Mitnick Lines Down How We Pay, Use, Value Grid Electricity Amid the Storm Lewis Latimer, The First Hidden Figure By Steve Mitnick Public Utilities Fortnightly Lines Up, Inc. Arlington, Virginia © 2021 Lines Up, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. The digital version of this publication may be freely shared in its full and final format. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020947176 Author: Steve Mitnick Editor: Lori Burkhart Assistant Editor: Angela Hawkinson Production: Mike Eacott Cover Design: Paul Kjellander Illustrations: Dennis Auth For information, contact: Lines Up, Inc. 3033 Wilson Blvd Suite 700 Arlington, VA 22201 First Printing, October 2020 V. 1.02 ISBN 978-1-7360142-0-2 Printed in the United States of America. To my boyhood heroes Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson, Elston Howard and Al Downing The cover painting entitled “Hidden in Bright Light,” is by Paul Kjellander, the President of the Idaho Public Utilities Commission and President of the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners, commonly referred to by its acronym NARUC. Table of Contents A Word of Inspiration by David Owens ................................ ix Sponsoring this Book and the PUF Latimer Scholarship Fund ............... xii Acknowledgements .............................................. xviii Note to Readers .................................................. xix Foreword ...................................................... xxiv Introduction ...................................................... 1 Chapter 1. The First Hidden Figure .............................. 7 First, and Alone .......................................... -

South by Southwest: Planter Emigration and Identity in the Slave South'

H-South Skelcher on Miller, 'South by Southwest: Planter Emigration and Identity in the Slave South' Review published on Sunday, August 1, 2004 James David Miller. South by Southwest: Planter Emigration and Identity in the Slave South. Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 2002. xi + 205 pp. $32.50 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8139-2117-4. Reviewed by Bradley Skelcher (Director of Graduate Program in Historic Preservation, Department of History, Political Science, and Philosophy, Delaware State University)Published on H-South (August, 2004) James David Miller in South by Southwest attempts to understand the relationship between the geographic mobility of the elite planter class and the development of a "distinctive world view" while maintaining certain conservative cultural traditions with origins in the American Southeast. The focus of this work is the emigration of elite planters from South Carolina and Georgia into Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas during the antebellum years between the 1820s and 1850s. Miller explores numerous and rich sources of information from newspapers and scientific journals along with private letters written by both men and women to explore private and public thoughts among the planter elite. Miller's central thesis revolves around the planter elite's ideology of conservatism. "Conservatism was, and is, itself an effort to come to terms with the modern world," Miller argues. "Indeed just as the rise of southern slavery itself has to be understood in relation to the development of the modern capitalist world, so too the planters' developing and distinctive world view cannot be understood apart from that world's cultural as well as economic life" (p. -

WAR ERA WASHINGTON, D.C., 1830-1865 Tamika Y. Richeson

CRIMES OF DISCONTENT: THE CONTOURS OF BLACK WOMEN’S LAW BREAKING IN CIVIL WAR ERA WASHINGTON, D.C., 1830-1865 Tamika Y. Richeson Charlottesville, Virginia Miami University of Ohio, B.A., 2007 Columbia University, M.A., 2008 University of Virginia, M.A., 2010 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty at the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia December 2014 Acknowledgements “Crimes of Discontent” would not be written had Rob Ellis not introduced me to the dusty stacks of the District of Columbia police precinct records at the National Archives. His kindness and patience with this “novice researcher” was critical to the concept of this dissertation. I have benefitted from numerous trips to the Library of Congress, the Library of Virginia, Maryland State Archives, and many efforts to make digitized collections available to students like myself. I have also received critical financial support from the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, the Raven Society, and the Scholar’s Lab at the University of Virginia. I owe a particular debt to the Scholar’s Lab for introducing me to the cutting-edge world of the digital humanities and for their patience and support for my ongoing digital project Black Women and the Civil War. My research is a product of my passion for black women’s history. For igniting my interest in black studies I have Rodney Coates to thank, and for introducing me to the methodological possibilities of history I owe a huge debt to my late mentor Manning Marable. Thank you to faculty members in the Corcoran Department of History, Claudrena Harold, S. -

Fighting for the Farms: Structural Violence, Race and Resistance In

© COPYRIGHT by Kalfani Nyerere Turè 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FIGHTING FOR THE FARMS: STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE, RACE AND RESISTANCE IN WASHINGTON, D.C. BY Kalfani Nyerere Turè ABSTRACT The goal of this dissertation research is to understand structural violence in the Barry Farm Public Dwellings, a public housing community in the District of Columbia (Washington, DC). The dissertation argues that a local urban renewal program called the New Communities Initiative (NCI), which is intended to end racialized urban ghettos in the District of Columbia, is a form of structural violence that instead continues inequality. The dissertation proposes an original explanatory framework based on a sociospatial binary of Western Superior Culture (WSC) and Non-Western Inferior Others/Truly “Truly” Disadvantaged Others (NWIO/TTDO). Poor African Americans represent the NWIO and the TTDO, its subset of increasingly vulnerable public housing residents. The dissertation argues that the elite WSC group dispenses structural violence to manufacture the NWIO/TTDO as an inferior status group and their environment as an African American urban ghetto (AAUG) and to maintain the NWIO/TTDO’s function as an antithetical reference group. I examine the Farms community both historically and in the contemporary moment to (1) discover structural violence’s real but hidden perpetrators; (2) to demystify structural violence by making sense of its perpetrators’ motivations; and (3) to understand the nature of its victims’ agency. Between 2007 and 2013, I utilized windshield tours, participant observation, interviews, archival research, and oral histories to collect ethnographic data. This dissertation’s analysis suggests that continuous structural violence has produced a fragmented community where history and cultural heritage are being lost and collective agency is difficult to form. -

CRITICAL RACE THEORY TIMELINE American History & Culture As a Metaphor for Race Interpreting History & Culture from an Afro-Centric Perspective

CRITICAL RACE THEORY TIMELINE American history & culture as a metaphor for race interpreting history & culture from an Afro-Centric perspective. Long before the Atlantic Slave Trade, great African Kingdoms (see back) made significant contributions to the world: engineering, science, chemistry, mathematics, art & culture, agriculture, the written language and civilization itself. These contributions continue in all of the Americas today! 1619-1865: 246 years of slavery - Slave Labor Camps 1866-1968: 103 years of Jim Crow - Domestic Terrorism 1969-present: 50+ years of "legal equality” 349 Years of White Supremacy Rise of White Nationalism TION TA PO N L A IC L E The P R L U Richmond N O A R W T A AY P SLAVE Review 1624 1640 1641 1676 1691 1706 1717 1746 1758 1773 1831 1858/1859 1898 1903 1919 1936 1967 1982 1998 2009 2020 First free Black John Punch, first MA is first Bacon’s South Carolina is First police New York First Quakers Phillis Wheatley 1802 1820 Nat Turner Anna Julia Cooper Paul Robeson W.E.B. Red Summer; Jesse 1960 MLK,Jr. Michael African Amer ican Civil Barack Murder of child born, Black enslaved via state to Rebellion first state to enact patrols enacts a black poet, prohibit publishes Poems on Sally Harriet slave revolt is born into slavery; is born; The DuBois The New Owens Ella speech at Jackson’s War Museum opens; Obama is George William Tucker VA court legalize begins “Slave Codes” around “Fugitive Lucy Terry, members Various Subjects, Hemings Tubman occurs in The John Brown Raid Wilmington, publishes Negro begins, wins 4 gold Baker Riverside; Thriller #1 Serena Williams #1 inaugurated Floyd slavery racialized plantations Slave Law” writes from Religious and Moral is revealed is born Virginia to end slavery North Carolina Souls of Alain Locke medals in establishes Loving vs.