Fighting for the Farms: Structural Violence, Race and Resistance In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rumson's Baby Parade. a Big Couotiw Supper

lEGI supper has extended a vote of RUMSON'S BABY PARADE. A BIG COUOTIW SUPPER. thanks to Robert S Johnson of RedSAFE BREAKERS JAILED, FAMED FOR HIS, Bank and to Joseph Lefferson, the IT WAS H^tlV'SATURDAY AT;KECORD-BREAKING CROWD AT caretaker of the school. Mr. John- TWO IMPORTANT ARRESTS S HEADLINES, FOR rpplyJI py and garden ' ^ yiCTORY,*AR_K. ) - COLT'S NECK LAST WEEK. son set up a radio ou.tfit and pro- MAdE AT NEW BRUNSWICK. NEW YORK PA ored bjr the art di- St. Mary'. Church Cleared More vided music during the supper, lir Red 'Bank Woman's Prize Fo> PntiitsTBaby Wai Woi Than »1,200 by Supper and Sale Lefferson did a big lot of work at John Miller and George Butler Rev. H. Pierce Slmpaoi, .,..jm iVI, Jld, on the clubhpwsp by Stanley' Allen Kerr—Tenni at Colt'j Neck Schpolbouae—More the echoolhouse. Charged With Robbing Three plete Program of Strennout W» Thn Son,IaTfipr jfmn.Tuesday. If this day ' Tournament Under Way—Chit Than 9Q0 Peraona Feaited. Placet at Belford and Port Mon- L«!d Out for the Balance of 1 Buiincii JW-jYterai'-H" V,1' f lnf should be stormy the exhibition will / dren'i Pageant. More than 900 persons were TEN BIG BOX BUSHES MOVED. mouth—Suspected of Others. August Vacation. - ' *.' s 1 WiH!Bm' Albert'BuVdgo of Broad^ .Evtrytnlng ia riadyfor tho annu- >e,heljl>e,eljl< thethe firfirsst clear day In Sep. Rurnson's annual baby parade wa servod at the annual chicken supper Two important arrests wcro made Rev. -

15 Lc 108 0380 Hr

15 LC 108 0380 House Resolution 957 By: Representatives Smyre of the 135th, Mosby of the 83rd, and Williams of the 168th A RESOLUTION 1 Honoring the life and memory of Marion Barry; and for other purposes. 2 WHEREAS, the State of Georgia mourns the loss of a great Civil Rights leader and public 3 servant with the passing of Marion Barry; and 4 WHEREAS, Marion Barry was born on March 6, 1936, in Itta Bena, Mississippi; and 5 WHEREAS, he earned a degree in chemistry from LeMoyne College in 1958, and while 6 earning his graduate degree in chemistry at Fisk University he organized a campus chapter 7 of the NAACP; and 8 WHEREAS, he was one of the student leaders who met with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in 9 1960 to establish the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and he was elected that 10 organization's first national chairman; and 11 WHEREAS, Marion Barry was elected mayor of Washington, D.C., in 1978, 1982, 1986, 12 and 1994, and during his tenure, he transformed that city from a jurisdiction run by the 13 federal government into a self-governing city and a mecca for African American politicians, 14 government administrators, businessmen, and intellectuals; and 15 WHEREAS, he was a dynamic leader, a wonderful friend, and a strategic master who strove 16 to serve the citizens of the District of Columbia to the best of his ability; and 17 WHEREAS, a compassionate and generous man, Marion Barry will long be remembered for 18 his love of the District of Columbia, and this loyal public servant and friend will be missed 19 by all who had the great fortune of knowing him. -

Traffic Impact Study 4600 N

Traffic Impact Study 4600 N. Marine Drive Residential Development Chicago, Illinois Prepared For: DRAFT May 28, 2021 Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables, ii I. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Existing Conditions ..................................................................................................................... 6 Site Location ............................................................................................................................... 6 Existing Street System Characteristics ....................................................................................... 6 Lake Shore Drive Improvement Study ....................................................................................... 9 Public Transportation .................................................................................................................. 9 Alternative Modes of Transportation ........................................................................................ 12 Existing Traffic Volumes .......................................................................................................... 13 3. Traffic Characteristics of the Proposed Development ................................................................... 16 Existing Site and Proposed Development -

Learning from History the Nashville Sit-In Campaign with Joanne Sheehan

Building a Culture of Peace Forum Learning From History The Nashville Sit-In Campaign with Joanne Sheehan Thursday, January 12, 2017 photo: James Garvin Ellis 7 to 9 pm (please arrive by 6:45 pm) Unitarian Universalist Church Free and 274 Pleasant Street, Concord NH 03301 Open to the Public Starting in September, 1959, the Rev. James Lawson began a series of workshops for African American college students and a few allies in Nashville to explore how Gandhian nonviolence could be applied to the struggle against racial segregation. Six months later, when other students in Greensboro, NC began a lunch counter sit-in, the Nashville group was ready. The sit- As the long-time New in movement launched the England Coordinator for Student Nonviolent Coordinating the War Resisters League, and as former Chair of War James Lawson Committee, which then played Photo: Joon Powell Resisters International, crucial roles in campaigns such Joanne Sheehan has decades as the Freedom Rides and Mississippi Freedom Summer. of experience in nonviolence training and education. Among those who attended Lawson nonviolence trainings She is co-author of WRI’s were students who would become significant leaders in the “Handbook for Nonviolent Civil Rights Movement, including Marion Barry, James Bevel, Campaigns.” Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, Diane Nash, and C. T. Vivian. For more information please Fifty-six years later, Joanne Sheehan uses the Nashville contact LR Berger, 603 496 1056 Campaign to help people learn how to develop and participate in strategic nonviolent campaigns which are more The Building a Culture of Peace Forum is sponsored by Pace e than protests, and which call for different roles and diverse Bene/Campaign Nonviolence, contributions. -

Final Report 2012

Underground Railroad Educational and Cultural Program Annual Report Model November 30, 2012 Underground Railroad Educational and Cultural Program CFDA 84.345 Project Name: Beneath the Underground and Beyond - The Flight to Freedom and Antebellum Communities in Maryland, 1830 - 1880: Resistance Along the Eastern Shore. Project Number: P345A105002 Project Director’s Name: Chris Haley Project Financial Manager’s Name: Nassir Resvan FY 2011 (October 2011 - September 30, 2012 Annual Report As per the URR Program’s Authorizing Legislation, The Maryland State Archives submits, for this fiscal year in which the organization received URR Program funding this report to the Secretary of Education that contains-- (A) A description of the programs and activities supported by the funding: • Using URR funds, the Maryland State Archives supported the work of its varied stakeholders of researchers, historians, curators and archivists by mining and making electronically accessible all the topics listed below: 1. Federal Census - Mining of the US Federal Census from the years 1830 - 1880 for the counties of Queen Anne, Kent and Dorchester Counties for all entries pertaining to free and enslaved Blacks - Census record mining involves the extraction of biographical data such as name, sex, age, race designation (Black or Mulatto), County District or Precinct, occupation, personal and real estate value and household status and entering that information into a searchable online database. Such information provides invaluable data for family historians, genealogists, scholars and historians whose research and subsequent products involve African American life during Maryland's 19th century before and after the Civil War. Due to funding from this grant, the Archives has been able to accumulate the following totals for the aforementioned counties: Federal Census Entries Year Queen Anne Kent Dorchester Total: 1830/1840 1,762 3,251 5,013 1850/1860 3 5,601 8,711 8,714 1870/1880 2,118 3,861 2,231 8,210 Total: 2,121 11,224 14,193 27,538 2. -

The Pearl Incident Packet

Handout 2 Student Name: _____________________________________ Date: ____________ Teacher:___________________________________________ Class Period: ____ The Pearl Incident Source Packet Document A Source: Excerpted from Daniel Drayton’s “Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton: For four years and four months a prisoner (for charity’s sake) in Washington jail” (1855). Retrieved from Library of Congress. Headnote: Daniel Drayton was the commander of the schooler The Pearl. He was an oyster fisherman who did not own this boat. He paid to borrow it from another man, name unknown, to complete the mission. It is said that Drayton had completed a mission to free enslaved people before, but demanded more and more payment for that mission. He was paid $100 dollars (a large sum for the time) to complete this mission. “Passing along the street, I met Captain Sayres, and knowing that he was sailing a small bay-craft, called The Pearl, and learning from him that business was dull with him, I proposed the enterprise to him...Captain Sayres engaged in this enterprise merely as a matter of business. I, too, was to be paid for my time and trouble,—an offer which the low state of my pecuniary (financial) affairs, and the necessity of supporting my family, did not allow me to decline. But this was not, by any means, my sole or principal motive. I undertook it out of sympathy for the enslaved, and from my desire to do something to further the cause of universal liberty. Such being the different ground upon which Sayres and myself stood, I did not think it necessary -

The Past and Future City: How Historic Preservation Is Reviving America's Communities

Notes Introduction 1. LA Conservancy, “Japanese-American Heritage,” https://www.laconser vancy.org/japanese-american-heritage. LA Conservancy, “The Maravilla Handball Court and El Centro Grocery Store,” https://www.laconser vancy.org/locations/maravilla-handball-court-and-el-centro-grocery. “Old Homies Pay Tribute to History, Handball, and a Woman Named Michi,” Eastsider LA, June 29, 2009, http://theeastsiderlahomehistory .blogspot.com/2009/06/old-hommies-play-tribute-to-history.html. Hec- tor Becerra, “Extending a Hand to a Faded East L.A. Handball Court,” Los Angeles Times, February 14, 2010, http://articles.latimes.com/2010 /feb/14/local/la-me-handball14-2010feb14. 2. LA Conservancy, “The Maravilla Handball Court.” Becerra, “Extending a Hand.” “Old Homies Pay Tribute.” 3. Becerra, “Extending a Hand.” “Old Homies Pay Tribute.” Newly Paul, “Group Works to Preserve East LA’s Maravilla Handball Court,” KPCC, February 23, 2010, http://www.scpr.org/news/2010/02/23/12216/group -works-preserve-east-las-maravilla-handball-c/. 4. Paul, “Group Works to Preserve East LA’s Maravilla Handball Court.” 5. Ibid. 6. Ibid. “East L.A. Handball Court Declared a State Historic Landmark,” Eastsider LA, August 7, 2012, http://www.theeastsiderla.com/2012/08 /east-l-a-handball-court-declared-a-state-historic-landmark/. 7. Maria Lewicka, “Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years?,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (2011): 211, 225; and Maria Lewicka, “Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 28 (2008): 211. Quoted in Tom Mayes, “Why Old Places Matter: Con- 263 Stephanie Meeks with Kevin C. -

Final Report 2011

Underground Railroad Educational and Cultural Program Annual Report Model November 30, 2012 Underground Railroad Educational and Cultural Program CFDA 84.345 Project Name: Beneath the Underground and Beyond - The Flight to Freedom and Antebellum Communities in Maryland, 1830 - 1880: Resistance Along the Eastern Shore. Project Number: P345A105002 Project Director’s Name: Chris Haley Project Financial Manager’s Name: Nassir Resvan FY 2011 (October 2010 - September 30, 2011 Annual Report As per the URR Program’s Authorizing Legislation, The Maryland State Archives submits, for this fiscal year in which the organization received URR Program funding this report to the Secretary of Education that contains-- (A) A description of the programs and activities supported by the funding: • Using URR funds, the Maryland State Archives supported the work of its varied stakeholders of researchers, historians, curators and archivists by mining and making electronically accessible all the topics listed below: 1. Federal Census - Federal Census from the years 1830 - 1880 for the counties of Caroline, Queen Anne and Dorchester County for all entries pertaining to free and enslaved Blacks - Census record mining involves the extraction of biographical data such as name, sex, age, race designation (Black or Mulatto), County District or Precinct, occupation, personal and real estate value and household status and entering that information into a searchable online database. Such information provides invaluable data for family historians, genealogists, scholars and historians whose research and subsequent products involve African American life during Maryland's 19th century before and after the Civil War. Due to funding from this grant, the Archives has been able to accumulate the following totals for the aforementioned counties: Federal Census Entries Year Caroline Queen Anne Dorchester Total 1830/1840 1,282 1,045 1,592 3,919 1850/1860 5,583 6,626 3,914 16,123 1870/1880 7,900 1 13,667 21,568 Total: 14,765 7,672 19,173 41,610 2. -

Traffic Impact Study for Mixed Used Development

Traffic Impact Study for the 3817-45 North Broadway Mixed-Use Development Chicago, Illinois Prepared by March 30, 2015 1. Introduction This report summarizes the methodologies, results and findings of a traffic impact study conducted by Kenig, Lindgren, O’Hara, Aboona, Inc. (KLOA, Inc.) for a proposed mixed-use development to be located In Chicago, Illinois. The site is located on the east side of North Broadway south of Sheridan Road and currently contains five one-to-three-story buildings. Overall the existing buildings provide approximately 58,500 square feet of commercial, office and residential space. The current plans call for 93 apartment units located above 32,732 square feet of office space on floors two and three and 19,600 square feet of ground floor retail space. In addition, the development is proposed to provide a below grade parking garage with 93 spaces that will be reserved for the residents of the proposed development. Access to the parking garage is to be provided from Grace Street via the existing public alley and a proposed right-in/right-out access drive on North Broadway. The following sections of this report present the following. Existing street conditions including vehicle, pedestrian, and bicycle traffic volumes for the weekday morning, weekday evening and Saturday midday peak hours A detailed description of the proposed development Vehicle trip generation for the proposed development Directional distribution of development-generated traffic Future transportation conditions including access to and from the development. The purpose of this study is three-fold: 1. To examine existing vehicle, pedestrian, and bicycle traffic conditions to establish a base condition. -

DCSEU Quarterly Report

Second Quarter Report for Fiscal Year 2014 January 1 – March 31, 2014 April 30, 2014 Table of Contents MESSAGE FROM THE MANAGING DIRECTOR ......................................................................................1 QUARTERLY FEATURE .........................................................................................................................2 1. At a Glance: Progress against Benchmarks ..............................................................................4 2. Core Area Performance ..........................................................................................................6 3. Initiative Activity....................................................................................................................7 4. Sector Highlights in the Core Areas .........................................................................................9 5. Activity Supporting DCSEU Programming .............................................................................. 13 MESSAGE FROM THE MANAGING DIRECTOR t is after a long and particularly difficult winter that we find ourselves reflecting on the issue of our climate. In March, the Intergovernmental IPanel on Climate Change released a new scientific assessment with one important and sobering assertion: Climate change is here, now. “Adaptation and mitigation choices in the near-term will affect the risks of climate change throughout the 21st century,” the report says, a reminder that we can do more to reduce our energy use and the resulting carbon emissions. -

Network Totals

Network Totals Total CBS 66 SYNDICATED 66 Netflix 51 Amazon 49 NBC 35 ABC 33 PBS 29 HBO 12 Disney Channel 12 Nickelodeon 12 Disney Junior 9 Food Network 9 Verizon go90 9 Universal Kids 6 Univision 6 YouTube RED 6 CNN en Español 5 DisneyXD 5 YouTube.com 5 OWN 4 Facebook Watch 3 Nat Geo Kids 3 A&E 2 Broadway HD 2 conversationsinla.com 2 Curious World 2 DIY Network 2 Ora TV 2 POP TV 2 venicetheseries.com 2 VICELAND 2 VME TV 2 Cartoon Network 1 Comcast Watchable 1 E! Entertainment 1 FOX 1 Fuse 1 Google Spotlight Stories/YouTube.com 1 Great Big Story 1 Hallmark Channel 1 Hulu 1 ION Television 1 Logo TV 1 manifest99.com 1 MTV 1 Multi-Platform Digital Distribution 1 Oculus Rift, Samsung Gear VR, Google Daydream, HTC Vive, Sony 1 PSVR sesamestreetincommunities.org 1 Telemundo 1 UMC 1 Program Totals Total General Hospital 26 Days of Our Lives 25 The Young and the Restless 25 The Bold and the Beautiful 18 The Bay The Series 15 Sesame Street 13 The Ellen DeGeneres Show 11 Odd Squad 8 Eastsiders 6 Free Rein 6 Harry 6 The Talk 6 Zac & Mia 6 A StoryBots Christmas 5 Annedroids 5 All Hail King Julien: Exiled 4 An American Girl Story - Ivy & Julie 1976: A Happy Balance 4 El Gordo y la Flaca 4 Family Feud 4 Jeopardy! 4 Live with Kelly and Ryan 4 Super Soul Sunday 4 The Price Is Right 4 The Stinky & Dirty Show 4 The View 4 A Chef's Life 3 All Hail King Julien 3 Cop and a Half: New Recruit 3 Dino Dana 3 Elena of Avalor 3 If You Give A Mouse A Cookie 3 Julie's Greenroom 3 Let's Make a Deal 3 Mind of A Chef 3 Pickler and Ben 3 Project Mc² 3 Relationship Status 3 Roman Atwood's Day Dreams 3 Steve Harvey 3 Tangled: The Series 3 The Real 3 Trollhunters 3 Tumble Leaf 3 1st Look 2 Ask This Old House 2 Beat Bugs: All Together Now 2 Blaze and the Monster Machines 2 Buddy Thunderstruck 2 Conversations in L.A. -

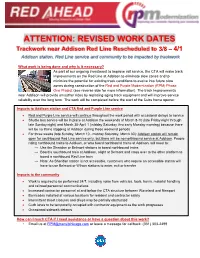

Attention: Revised Work Dates

ATTENTION: REVISED WORK DATES Trackwork near Addison Red Line Rescheduled to 3/8 – 4/1 InformationAddison station, for Red Residents Line service and, Businessescommunity to be impacted and Customers by trackwork What work is being done and why is it necessary? As part of our ongoing investment to improve rail service, the CTA will make track improvements on the Red Line at Addison to eliminate slow zones and to minimize the potential for existing track conditions to evolve into future slow zones during construction of the Red and Purple Modernization (RPM) Phase One Project (see reverse side for more information). The track improvements near Addison will provide smoother rides by replacing aging track equipment and will improve service reliability over the long term. The work will be completed before the start of the Cubs home opener. Impacts to Addison station and CTA Red and Purple Line service Red and Purple Line service will continue throughout the work period with occasional delays to service S huttle bus service will be in place at Addison the weekends of March 8-10 (late Friday night through late Sunday night) and March 30-April 1 (midday Saturday thru early Monday morning) because there will be no trains stopping at Addison during these weekend periods For three weeks (late Sunday, March 10 - midday Saturday, March 30): Addison station will remain open for southbound Red Line service only, but there will be no northbound service at Addison. People riding northbound trains to Addison, or who board northbound trains at Addison,