Introduction in the Year 1840, Our Continent, in Terms of Chess, Was A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

Dutchman Who Did Not Drink Beer. He Also Surprised My Wife Nina by Showing up with Flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital Just Before She Gave Birth to My Son Mitchell

168 The Bobby Fischer I Knew and Other Stories Dutchman who did not drink beer. He also surprised my wife Nina by showing up with flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital just before she gave birth to my son Mitchell. I hadn't said peep, but he had his quiet ways of finding out. Max was quiet in another way. He never discussed his heroism during the Nazi occupation. Yet not only did he write letters to Alekhine asking the latter to intercede on behalf of the Dutch martyrs, Dr. Gerard Oskam and Salo Landau, he also put his life or at least his liberty on the line for several others. I learned of one instance from Max's friend, Hans Kmoch, the famous in-house annotator at AI Horowitz's Chess Review. Hans was living at the time on Central Park West somewhere in the Eighties. His wife Trudy, a Jew, had constant nightmares about her interrogations and beatings in Holland by the Nazis. Hans had little money, and Trudy spent much of the day in bed screaming. Enter Nina. My wife was working in the New York City welfare system and managed to get them part-time assistance. Hans then confided in me about how Dr. E greased palms and used his in fluence to save Trudy's life by keeping her out of a concentration camp. But mind you, I heard this from Hans, not from Dr. E, who was always Max the mum about his good deeds. Mr. President In 1970, Max Euwe was elected president of FIDE, a position he held until 1978. -

Was a German Chess Master. He Participated Many Times in Berlin

Otto Wegemund Otto Wegemund (1870 – 5 October 1928) was a German chess master. He participated many times in Berlin City Chess Championship; took 6th in 1906 (Erich Cohn won), took 10th in 1908 (Wilhelm Cohn won), took 10th in 1910 (Carl Ahues won), tied for 7-8th in 1920 (Ernst Schweinburg won), tied for 5-6th in 1924 (Ahues and Richard Teichmann won), shared 4th in 1925 (Friedrich Sämisch won), and tied for 9-10th in 1927 (Berthold Koch won).[1] He also played several times in the DSB Congress. Among others, he shared 6th at Coburg 1904 (Hauptturnier B, Hans Fahrni won), took 9th at Breslau 1912 (Hauptturnier B, Paul Krüger won), shared 1st with Wilhelm Hilse at Hamburg 1921 (Hauptturnier B), tied for 8-10th at Bad Oeynhausen 1922 (Ehrhardt Post won),[2] and took 8th at Frankfurt 1923 (Ernst Grünfeld won).[3] In other tournaments, he took 5th at Berlin 1917 (Walter John and Paul Johner won),[4] took 2nd, behind John, at Breslau 1918,[5] and took 11th at Berlin 1920 (Alexey Selezniev won). References 1. Jump up^ http://www.berlinerschachverband.de/archiv/events/bsv/bem/190 0.html 2. Jump up^ Name Index to Jeremy Gaige's Chess Tournament Crosstables 3. Jump up^ http://xoomer.alice.it/cserica/scacchi/storiascacchi/tornei/1900- 49/1923frankfurt.htm 4. Jump up^ http://xoomer.alice.it/cserica/scacchi/storiascacchi/profili/fino194 5.htm 5. Jump up^ http://www.astercity.net/~vistula/fredvandervliet.htm Otto Wegemund Number of games in database: 29 Years covered: 1904 to 1923 Overall record: +7 -17 =5 (32.8%)* * Overall winning percentage = (wins+draws/2) / total games Based on games in the database; may be incomplete. -

Auction No. 14, 29 September – 1 October 2005

Auction No. 14, 29 September – 1 October 2005 Lot 1. O. A. Brownson Jr. Book of the Second American Chess Congress Held at Cleveland, Ohio. 1871. Dubuque, (1871). Including the report of the examining committee on the Problem Tournament. L/N 5198, Betts 25-8. Original binding with gilt cloth spine and marbled paper boards. Condition very good. This copy is very rare with the photographs of Max Judd (frontispiece) and Theodore M. Brown. Sold for €601.84 Lot 2. Two tournament books bound together: 1) Emil Schallopp, “Der Schachwettkampf zwischen Wilh. Steinitz und J. H. Zukertort, Anfang 1886.” Leipzig, 1886. L/N 5026. 48 pages. 2) E. Bogolyubov, “Schachkampf um die Weltmeisterschaft zwischen Dr. A. Alekhine (Paris) und E. Bogoljubov (Triberg) in Deutschland 1934.” Karlsruhe (1935). L/N 5091. 127 pages. Bound in cloth with gilt upper cover. A small stain (water) on the spine extending to the covers, pen sign (name of previous owner) on the title page of the Bogoljubov book, otherwise condition fine. Sold for €77 Lot 3. A memorial of an invitation chess tournament for masters and amateurs arranged by the city of London chess club. London, 1900. L/N 5254. Original board covers slightly soiled, corners bumped, light foxing; otherwise clean and sound. Sold for €80 Lot 4. Georg Marco, Das Internationale Gambitturnier in Wiener Schaklub, 1903. Wien (1911). L/N 5265. 115 pages. Gilt sloth spine with marble paperboards. Some foxing to the title-page and several other pages, a few minor pencil marks in the book, repair to page 115 (without loss of text), otherwise condition is very good. -

The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants

THE CLASSIFIED ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CHESS VARIANTS I once read a story about the discovery of a strange tribe somewhere in the Amazon basin. An eminent anthropologist recalls that there was some evidence that a space ship from Mars had landed in the area a millenium or two earlier. ‘Good heavens,’ exclaims the narrator, are you suggesting that this tribe are the descendants of Martians?’ ‘Certainly not,’ snaps the learned man, ‘they are the original Earth-people — it is we who are the Martians.’ Reflect that chess is but an imperfect variant of a game that was itself a variant of a germinal game whose origins lie somewhere in the darkness of time. The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants D. B. Pritchard The second edition of The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants completed and edited by John Beasley Copyright © the estate of David Pritchard 2007 Published by John Beasley 7 St James Road Harpenden Herts AL5 4NX GB - England ISBN 978-0-9555168-0-1 Typeset by John Beasley Originally printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn Contents Introduction to the second edition 13 Author’s acknowledgements 16 Editor’s acknowledgements 17 Warning regarding proprietary games 18 Part 1 Games using an ordinary board and men 19 1 Two or more moves at a time 21 1.1 Two moves at a turn, intermediate check observed 21 1.2 Two moves at a turn, intermediate check ignored 24 1.3 Two moves against one 25 1.4 Three to ten moves at a turn 26 1.5 One more move each time 28 1.6 Every man can move 32 1.7 Other kinds of multiple movement 32 2 Games with concealed -

GM Square Auction No. 20, 12-15 February 2009

GM Square Auction No. 20, 12-15 February 2009 http://www.gmsquare.com/chessauction/index.html Lot 1. BCM, volume I (1881, August to December) and volume II (1882, 392 pages, complete). Volume 1 is incomplete (starts from August; pages 257-400). Nicely bound as one volume together with indices for both years. Bound in half leather with marbled boards, marbled endpapers and edges, and gilt tickets to spine. Very good condition. Sold for €380.53 Lot 2. BCM, volume X (1890). 512 pages, complete with index. Nicely bound in half leather with marbled boards and endpapers, sprinkled edges and gilt tickets to spine. Fine condition. Sold for €394.08 Lot 3. BCM, volume XI (1891). 568 pages, complete with index. Nicely bound in half leather with marbled boards and endpapers, sprinkled edges and gilt ticket to spine. Light foxing to some pages, otherwise in fine condition. Sold for €410 Lot 4. BCM, volume XIII (1893). 558 pages, complete with index. Nicely bound in half leather with marbled boards and endpapers, and gilt ticket to spine. Very good condition. Sold for €316.99 Lot 5. BCM, volume No. 70 (1950). 412 pages, index. Bound in blue buckram, with gilt tickets to spine. Paper slightly browned, very good. Sold for €42.09 Lot 6. BCM, volumes No. 80-82 (1960, 1961 and 1962). 364, 364 and 372 pages respectively. All with index, all bound in blue buckram, with gilt tickets to spine. All are in very good condition. Sold for €66 Lot 7. Caissa magazine (Germany), volumes 2-7. (1948-1953). -

Schachspieler Bevorzugen Die W Ie N E R Schach-Zeitung Das Führende Weltschachorgan

iHKHiIR* HIB« ZEIT- KHRIlFTiBil-BCÄTAE,©^ OER WIENER KHÄ£H~gEDTMMCi Mit Bildnissen und einem Anhang: „LESEPROBEN AUS DIVERSER JAHRGÄNGEN OER WIENER SCHOCH-ZEITUNG" IM ® « 6 10 3 2 VERLAG; WIEN, IV., WIEONER HAUPTSTRASSE 11 POSTVERSAND NACH ALLEN LÄNDERN SCHACHSPIELER BEVORZUGEN DIE W IE N E R SCHACH-ZEITUNG DAS FÜHRENDE WELTSCHACHORGAN PROBENÜftMER GRATIS! MARCO M otto: . Ich aber sage jedem, der Fortschritte machen will: eher wird ein Kamel durch ein Nadelöhr spazieren, als ein Denkfauler den Tempel Caissas betreten.“ Marco. D. W i K t Ä « W i M E DER WOEIMEEI $<HA<H~ZEITIJNG „Im Verlag der Wiener Schach-Zeitung sind die besten Publikationen der Schachliteratur erschienen.“ (Radio Lwow am 21. IK. 1931.) Dr. S. G, Tartakower, „Die hypermoderne Schachpartie" 517 Seiten Großoktav Elegant gebunden M 18.— Z. A u f l a g e Auch in Folgen ä M 2.— erhältlich Original - E inbanddecke M 1.50 öas Standardw erk der letzten Jalrre. Ein Schachlehr- und Lesebuch, zugleich eine Sammlung von 150 der schönsten Meisterpartien aus den Jah ren 1914—1925, je n e r E poche, die einen ungeahnten Aufstieg des Schachspiels be deutet. Mit plastischer Methode behandelt der hervorragende Schachkenner und Schriftsteller D r. S. G. T arta k o w er in diesem Werke nicht nur das Variantenmäßige, sondern an der Hand besonders markanter Beispiele auch das Wesen des neuen hypermodernen Sphachs. Das Werk ist ganz vorzüglich ausgestattet; neben vielen Dia grammen bringt es die Bilder einer großen Zahl von Meistern. Ein ausführliches analytisches In haltsverzeichnis erleichtert das Studium im hohen Maße. Der vornehm-gediegene und haltbare Ein band in Ganzleinen macht das Werk zu einem Glanzstück in jeder Schachbücherei. -

GM Square Auction No. 19, 12-14 June 2008

GM Square Auction No. 19, 12-14 June 2008 http://www.gmsquare.com/chessauction/index.html Lot 1. H. Fähndrich “Internationales Kaiser-Jubiläums-Schachturnier Wien 1898” Vienna, (1898). 351 pages. L/N 5250. Bound in blue cloth with gilt spine. Corners of some pages are cut off without any loss of text; bottom of pages 69-76 (about 10 mm) is cut off without any loss of text. This probably happened when the book was produced. Paper slightly browned, otherwise fine. Unsold Lot 2. Traite des Echecs et Recueil des Parties jouees au Tournoi International de 1900 par S. Rosenthal. Paris 1901. L/N 5256. 382 pages. Bound in black cloth with gilt spine. Edges stained red. Paper slightly browned, the title-page is torn in the upper right corner, numerous small pencil marks (ticks near the game numbers), otherwise very good. Sold for €307.92 Lot 3. Der Dreizehnte Kongress des Deutschen Schachbundes. Hannover 1902. By Prof. Dr. Gebhardt, J. Metger, Dir. J. Berger and C. Schultz. Leipzig, 1902. 204 pages. L/N 5259. Paperboards, free endpapers are detached but present, occasional small marks (ticks) near game numbers, otherwise fine. Sold for €40 Lot 4. Der Vierzehnte Kongress des Deutschen Schachbundes. Coburg 1904. By Paul Schellenberg, Carl Schlechter and Georg Marco. Leipzig, 1905. 144 pages. L/N 5267. Paperboards, occasional small marks (ticks) near game numbers, fine. Sold for €55 Lot 5. “Der funfzehnte Kongress des Deutschen Schachbundes zu Nurnberg 1906” by S. Tarrasch and J. Schenzel. Leipzig, 1906. S-5278. 278 pages. Bound in blue cloth with gilt spine. -

Soltis Marshall 200 Games.Pdf

TO THE MARSHALL CHESS CLUB FRANK MARSHALL, UNITED STATES CHESS CHAMPION A Biography with 220 Games by Grandmaster Andy Soltis McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data are available Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Soltis, Andy, 1947- Frank Marshall, United States chess champion : a biography with 220 games / by Andy Soltis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Q ISBN-13: 978-0-89950-887-0 (lib. bdg. : 50# alk. paper) � I. Marshall, Frank James, 1877-1944. 2. Chess players- United States- Biography. I. Title. GV1439.M35S65 1994 794.l'S9 - dc20 92-56699 CIP ©1994 Andy Soltis. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 CONTENTS Preface IX One: When Chess Was Young 1 Two: Paris 1900 14 Three: Sophomore Marshall 26 Four: Cambridge Springs 57 Five: Consistently Inconsistent 73 Six: Candidate Marshall 98 Seven: The Longest Trip 116 Between pages 152 and 153 are 8 pages of plates containing 14 photographs Eight: A Year at Home 153 Nine: Swindle! 167 Ten: The Great Tournaments 175 Eleven: Farewell to Europe 207 Twelve: The War Years 230 Thirteen: The House That Marshall Built 245 Fourteen: Another Lasker 255 Fifteen: European Comeback 273 Sixteen: A Lion in Winter 292 Se,:enteen: The Gold Medals 320 Eighteen: Sunset 340 Tournament and Match Record 365 Bibliography 369 Index 373 v Preface My first serious contact with chess began when, as a high school sophomore, I took a board in a simultaneous exhibition at the Marshall Chess Club. -

Das Turnier Von Hastings 1895

Das Turnier von Hastings 1895 Stehend: Adolf Albin, Carl Schlechter, Dawid Janowski, Georg Marco, Joseph Henry Blackburne, Geza Maróczy, Emanuel Schiffers, Isidor Gunsberg, Amos Burn, Samuel Tinsley Sitzend: Beniamino Vergani, Wilhelm Steinitz, Michail Tschigorin, Emanuel Lasker, Harry Nelson Pillsbury, Siegbert Tarrasch, Jacques Mieses, Richard Teichmann Nicht auf dem Bild: Curt von Bardeleben, James Mason, Carl August Walbrodt, Henry Edward Bird, William Pollock Das Turnier war das am stärksten besetzte Turnier in der bisherigen Geschichte des Schachs und fand zwischen dem 5. August und 2. September 1895 statt. Alle Topspieler dieser Zeit warten anwesend. Im Turnierbuch haben die Teilnehmer ihre Partien niedergeschrieben. Einige Partien wurden auch von anderen Turnierteilnehmern kommentiert. Das Turnier war ein derartiger Erfolg, dass es danach ein alljährliches Turnier wurde. Beim Abschlussbankett lud Michail Tschigorin die fünf ersten Plätze dieses Turniers zu einem Turnier nach Sankt Petersburg im Dezember desselben Jahres ein. Berühmte Partien Viele Spiele waren von hoher Qualität und hart umkämpft. Die berühmteste Partie stammte aus der zehnten Runde: Wilhelm Steinitz – Curt von Bardeleben. Diese Partie wurde auch mit dem Schönheitspreis des Turniers ausgezeichnet. Der Entstand 1. Harry Nelson Pillsbury USA 16,5 2. Michail Tschigorin Russland 16 3. Emanuel Lasker Deutsches Reich 15,5 4. Siegbert Tarrasch Deutsches Reich 14 5. Wilhelm Steinitz USA 13 6. Emanuel Schiffers Russland 12 7. Curt von Bardeleben Deutsches Reich 11,5 Richard Teichmann Deutsches Reich 11,5 9. Carl Schlechter Österreich-Ungarn 11 10. Joseph Henry Blackburne England 10,5 11. Carl August Walbrodt Deutsches Reich 10 12. Dawid Janowski Frankreich 9,5 James Mason England 9,5 Amos Burn England 9,5 15. -

Las Combinaciones

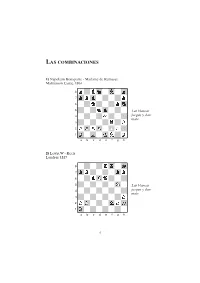

LAS COMBINACIONES 1) Napoleón Bonaparte - Madame de Remusat Malmaison Castle, 1804 8 7 6 5 Las blancas 4 juegan y dan mate 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h 12.¥c4+! Rxc4 (12...¢d4 13.£d3#) 13.£b3+ ¢d4 14.£d3# 1-0 2) Lewis, W - Keen Londres, 1817 8 7 6 5 Las blancas 4 juegan y dan mate 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h 27.¤f7+ ¢g8 (27...¦xf7 28.£xe8+) 28.¤h6+ ¢h8 29.£g8+! ¦xg8 30.¤f7# 1-0 9 LOS PROTAGONISTAS Napoleón Bonaparte General Henri-Gratien Alexander D Petroff (1769 a 1821) Bertrand (1773 a 1844) (1794 a 1867) Louis Charles Mahé Alonzo Morphy (padre John Cochrane de Labourdonnais de Paul Morphy) (1798 a 1878) (1797 a 1840) (1798 a 1856) Joseph Szen Ernest Morphy (tío de Capitán Hugh (1800 a 1857) Paul Morphy) Alexander Kennedy (1807 a 1874) (1809 a 1874) Howard Staunton Janos Jakab Löwenthal Carl Friedrich A (1810 a 1874) (1810 a 1876) Jaenisch (1813 a 1872) 259 500 COMBINACIONES DEL SIGLO XIX Juez Alexander Adolf Anderssen Tassilo Von Beaufort Meek (1818 a 1878) Heydebrand und der (1814 a 1865) Lasa (1818 a 1899) Ilya Shumov Henry Thomas Buckle Daniel Harrwitz (1819 a 1881) (1821 a 1862) (1823 a 1884) Wilfried Paulsen (her- Reverendo Charles Jules Arnous de mano de Louis Edward Ranken Riviere (1830 a 1906) Paulsen) (1828 a 1901) (1828 a 1905) Henry Edward Bird Max Lange Louis Paulsen (1830 a 1908) (1832 a 1899) (1833 a 1891) 260 LOS PROTAGONISTAS James Mortimer James Adams Congdon Wilhelm Steinitz (1833 a 1911) (1835 a 1902) (1836 a 1900) Paul Charles Morphy Barón Ignaz Von George Henry (1837 a 1884) Kolisch (1837 a 1889) Mackenzie (1837 a 1891) Samuel -

Nuestro Círculo

Nuestro Círculo Año 7 Nº 323 Semanario de Ajedrez 11 de octubre de 2006 GEORG MARCO Tdc7 33.g4 hxg4 34.hxg4 Ce7 35.Te3 Tc2 0- Dc7 34.Dd2 Re8 35.h4 Th7 36.Td6 Dc8 1 37.Da5 a6 38.c4 Th8 39.Dc5 Dc7 40.e6 1-0 1863-1923 James Mason - Georg Marco [C27] Leipzig, 1894 Georg Marco - Carl Schlechter [C00] Nuremberg, 1896 1.e4 e5 2.Cc3 Cf6 3.Ac4 Cxe4 4.Axf7+ Rxf7 5.Cxe4 d5 6.Df3+ Rg8 7.Ce2 Ae6 8.Db3 Cc6 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Ad3 c5 4.exd5 exd5 5.dxc5 9.C4g3 Tb8 10.c3 Df6 11.0-0 h5 12.Te1 h4 Axc5 6.Cf3 Cf6 7.0-0 0-0 8.Cc3 Cc6 9.Ag5 13.Cf1 h3 14.Ceg3 hxg2 15.Rxg2 Ac5 16.d4 Ae6 10.Dd2 Ae7 11.Tad1 Da5 12.a3 Tad8 Tf8 17.Dc2 Df3+ 18.Rg1 Ah3 19.Ce3 exd4 13.Dc1 a6 14.h3 Tfe8 15.b4 Dc7 16.Af4 Dc8 20.cxd4 Cxd4 21.Dd2 Dxg3+ 22.fxg3 Cf3+ 17.Ce2 Ce4 18.Db2 Af6 19.c3 Cd6 20.Axd6 23.Rh1 Cxd2 24.Axd2 Tf2 25.Tad1 Th5 Txd6 21.Ced4 Ad7 22.Tfe1 g6 23.Txe8+ 26.Ac1 c6 27.Rg1 Tg2+ 28.Rh1 Tf2 29.Rg1 Dxe8 24.Te1 Dc8 25.b5 Cxd4 26.cxd4 Tb6 Tg2+ 30.Rh1 Tf2 31.Rg1 Tf3 32.Rh1 Tf2 27.a4 axb5 28.axb5 Te6 29.Txe6 Axe6 33.Rg1 Tf4 34.Rh1 Tf2 35.Rg1 Tg2+ 36.Rh1 30.Dc2 Dxc2 31.Axc2 Rf8 32.Rf1 Re7 Tf2 37.Rg1 Tg2+ 38.Rh1 Tf2 39.Rg1 Tf3 33.Re2 Rd6 34.Rd2 Rc7 35.Rc3 Rb6 36.Rb4 40.Rh1 Tf2 41.Rg1 Thf5 42.a3 Tg2+ 43.Rh1 Ae7+ 37.Ra4 Ad6 38.Cg5 Af8 39.Cxe6 fxe6 Tff2 44.Cf1 Tg1+ 45.Rxg1 Txf1# 0-1 40.h4 Ag7 41.h5 Axd4 42.hxg6 hxg6 43.Axg6 e5 44.f3 Af2 45.g4 Rc5 46.Ad3 Rd4 47.g5 Georg Marco - Joseph Henry Blackburne Ah4 48.g6 Af6 49.Af5 b6 50.Rb3 Re3 51.Ag4 [B01] Nuremberg, 1896 Rf4 52.Ah5 Rg5 53.Ag4 d4 54.Ae6 Rf4 55.Ad5 Re3 56.Rc2 Re2 57.Ae4 Ag7 58.Af5 1.e4 d5 2.exd5 Cf6 3.d4 Cxd5 4.c4 Cf6 Rxf3