Soltis Marshall 200 Games.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

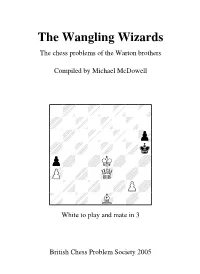

The Wangling Wizards the Chess Problems of the Warton Brothers

The Wangling Wizards The chess problems of the Warton brothers Compiled by Michael McDowell ½ û White to play and mate in 3 British Chess Problem Society 2005 The Wangling Wizards Introduction Tom and Joe Warton were two of the most popular British chess problem composers of the twentieth century. They were often compared to the American "Puzzle King" Sam Loyd because they rarely composed problems illustrating formal themes, instead directing their energies towards hoodwinking the solver. Piquant keys and well-concealed manoeuvres formed the basis of a style that became known as "Wartonesque" and earned the brothers the nickname "the Wangling Wizards". Thomas Joseph Warton was born on 18 th July 1885 at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, and Joseph John Warton on 22 nd September 1900 at Notting Hill, London. Another brother, Edwin, also composed problems, and there may have been a fourth composing Warton, as a two-mover appeared in the August 1916 issue of the Chess Amateur under the name G. F. Warton. After a brief flourish Edwin abandoned composition, although as late as 1946 he published a problem in Chess . Tom and Joe began composing around 1913. After Tom’s early retirement from the Metropolitan Police Force they churned out problems by the hundred, both individually and as a duo, their total output having been estimated at over 2600 problems. Tom died on 23rd May 1955. Joe continued to compose, and in the 1960s published a number of joints with Jim Cresswell, problem editor of the Busmen's Chess Review , who shared his liking for mutates. Many pleasing works appeared in the BCR under their amusing pseudonym "Wartocress". -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Wolfgan • As-:=;:..S~ ;

Boris Wolfgan • as-:=;:..s~ ; . = tI. s. s. R. nZlC· WEST GERt1t ,------------------------------------ -----------, USCF BRINGS YOU The very newest chess teaching sensation, available immediately to members! Learn ta think the same way Bobby does. Learn by progressive understanding, not just by reading. Learn through the insight and talent af our greatest player, brought to you in easily absarbed, progressive, Programmed Instructian! A new method for learning chess hos been created by the education division of Xerox Corporation and co-authored by the youthful United States Chess Champion. The system is unique in that it is easy to understand, trains the player to think four moves ahead, and does not require the use of 0 chess board nor the Icarning of chess notation. It hos solved many long.standing proble ms in teaching chess and presents the course as a tutor would to a stude nt. The learner becomes on active participant from the very beginning by acting on 275 differe nt chess situations and immediately putting to use the new idea expressed with coch position. The reade r of this book require s no prior chess knowledge becouse of the introduction on rules and moves and the fact that chess notation is not used. Designed primarily for the beginner, " Bobby fischer Teaches Chess" will be inte resting to players in every category. Lower-rated USCF tourname nt players will find the course especially interesting, since al most every page contains (II problem-solving situation. The book is writte n in the first per son, with Fischer actually " talking" to the learne r-correcting and coaching him through the program like (II private tutor. -

THE DALLAS TOURNAMENT New York State Championship Santasiere + Sturgis + Reinfeld + White

HONOR PRIZE PROBLEM THOMAS S. McKENNA Lima, Ohio M-ATE IN FOUR MOVES TH&OFFICIAL ORGAN OfTHB UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CHESS FEDERATION THE DALLAS TOURNAMENT New York State Championship Santasiere + Sturgis + Reinfeld + White -===~--~ I OCTOBER, 1940 MONTHLY 30 cents ANNUALLY $3.00 OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Vol. VIII, No.7 Publhhl!d M01llhly October, 1940 CHESS FEDERATION Published bi· monthly June · September; published monthly October · May by THE CHESS REVIEW, 25 West 43.rd Street, New York, N. Y. Telephone WlsconSln 7·3742. Domestic subscriptions: One Year $3.00; Two Years $5 .50; Five Years $12.50. Single copy 30 cents. Foreign subscriptions: $3.50 per year ex(ept U. S. Possessions, Canada, Mexico, Central and South Am erica. Sin gl e (Opy. 30 cents. Copyright 1939 by THE CHESS REVIEW "Reentered as second class matter July 26, 1940, at REVIEWI. A. HOROWiTZ . the post office at New York, N. Y ., under the Act FRED REINFELD of March 3, 1879. Editors World Championship One other aspect of the situation is worth noting: according to a T ;meJ interview, Capa. Run Around blanca stated that "aside from himself" the By FRED REINFELD most suitable candidates for a Championship Chess players will be delighted to hear that Match were Paul Keres and Mikhail Botvinnik. Dr. Alekhine's whereabouts have now been Having read t.his sort of thing more than once, ascertained, for the New York TimeJ reports I cannot aVOId the suspicion that these two that he recently communicated with J. R. Capa. players are hvored because of their geographi_ blanca regarding the world championship title. -

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1 “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION 2013, Botswana Chess Review In this Issue; BY: KEENESE NEOYAME KATISENGE 1. Historic World Chess Federation’s Visit to Botswana 2. Field Performance 3. Administration & Developmental Programs BCF PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTOR 4. Social Responsibility, Marketing and Publicity / Sponsorships B “Checkmate” is the first edition of BCF e-Newsletter. It will be released on a quarterly basis with a review of chess events for the past period. In Chess circles, “Checkmate” announces the end of the game the same way this newsletter reviews performance at the end of a specified period. The aim of “Checkmate” is to maintain contact with all stakeholders, share information with interesting chess highlights as well as increase awareness in a BNSC Chair Solly Reikeletseng,Mr Mogotsi from Debswana, cost-effective manner. Mr Bobby Gaseitsewe from BNSC and BCF Exo during The 2013 Re-ba bona-ha Youth Championships 2013, Botswana Chess Review Under the leadership of the new president, Tshenolo Maruatona,, Botswana Chess continues to steadily Minister of Youth, Sports & Culture Hon. Shaw Kgathi and cement its place as one of the fastest growing the FIDE Delegation during their visit to Botswana in 2013 sporting codes in the country. BCF has held a number of activities aimed at developing and growing the sport in the country. “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION | Issue 1 2 2013 Review Cont.. The president of the federation, Mr Maruatona attended two key International Congresses, i.e Zonal Meeting held during The -

Federación Española De Ajedrez

PHEJD: FEDERACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE AJEDREZ PATRIMONIO HISTÓRICO ESPAÑOL DEL JUEGO Y DEL DEPORTE: FEDERACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE AJREDEZ Javier Rodríguez Álvaro Regalado 2012 MUSEO DEL JUEGO Javier Rodríguez, Álvaro Regalado PHEJD: FEDERACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE AJEDREZ Índice 1. Introducción. 2. Historia del ajedrez. 3. Orígenes, precedentes y creación de la FEDA 4. Primera junta directiva y primera asamblea 5. Historia y evolución de la FEDA: presidentes, competiciones oficiales. 6. Estructura actual de la FEDA 7. Campeonatos de España 8. Programa de formación de técnicos y jugadores 9. Bibliografía 10.Índice de ilustraciones 11. Anexo: Reglas del juego MUSEO DEL JUEGO Javier Rodríguez, Álvaro Regalado PHEJD: FEDERACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE AJEDREZ 1. INTRODUCCION El conjunto del juego de ajedrez con el tablero y las piezas colocadas en posición inicial nos hace recordar un campo de batalla, definido por unos límites en el cual se enfrentan dos ejércitos claramente diferenciados prestos a entrar en combate. Las 64 casillas por donde ha de discurrir la confrontación están bien diferenciadas, siendo de color claro la mitad de ellas y la otra mitad, de color oscuro. Nos puede correr la imaginación con multitud de batallas disputadas en este mundo claramente definido, haciéndonos retroceder en el tiempo donde la caballerosidad y las reglas estrictas de lucha marcaban las pautas de la batalla. 1. Piezas de Shatranj A través del mismo nos llega un modelo de sociedad militar donde se reflejan las grandes gestas (la heroica coronación del peón y su transformación después de todas las penalidades pasadas) y miserias que se producen (la perdición de un gran ejercito debido a la rápida acción de un comando suicida). -

Republik Oesterreich

REPUBLIK ÖSTERREICH Organe der Bundesgesetzgebung. Wien, I/1, Parlamentsring 3, Tel. A19-500/9 Serie, A24-5-75. Dienststunden: Montag bis Freitag von 8 bis 16 Uhr, Samstag von 8 bis 12 Uhr. Nationalrat. Präsident: Leopold Kunschak. Zweiter Präsident: Johann Böhm. Dritter Präsident: Dr. Alfons Gorbach. Mitglieder. Cerny Theodor, Steinmetz- _ Scheff Otto, Dr., Rechtsanwalt; meister; Gmünd. ÖVP. Maria-Enzersdorf. ÖVP. (LB. = LirLksblock, Kommunistische Partei Österreichs. Dengler Josef, Arbeitersekretär; Scheibenreif Alois, Bauer; ÖVP. = Österreichische Volkspartei. — Wien. ÖVP. Reith 5 bei Neunkirchen. ÖVP. SPÖ. = Sozialistische Partei Österreichs. — VdU. = Verband der Unabhängigen.) Ehrenfried Anton, Beamter; Schneeberger Pius, Forstarbeiter; Hollabrunn. ÖVP. Wien. Burgenland. Eichinger Karl, Bauer; Wind— _ Seidl Georg, Bauer; Gaubitsch 76, passing 6. ÖVP. Post Unterstinkenbrunn. ÖVP Böhm Johann, Zweiter Präsident des Nationalrates; Wien. SPÖ. Figl Leopold, Dr. h. c., Ing., Singer Rudolf, Aufzugsmonteur; Bundeskanzler; Wien. ÖVP. St. Pölten. SPÖ. Frisch Anton, Hofrat, Landes— schulinspektor; Wien, ÖVP. Fischer Leopold, Weinbauer; Solar Lola, Fachlehrerin; Wien- Sooß, Post Baden bei Wien. ÖVP. Mödling. ÖVP. Nedwal Andreas, Landwirt; Gerersdorf bei Güssing. ÖVP. Floßmann Ferdinanda. Strasser Peter, Techniker; Wien. SPÖ. Privatangestellte; Wien. SPÖ. Nemecz Alexander, Dr., Rechts- Strommer Josef, Bauer; Mold 4, anwalt; Oberwarth 119 b. ÖVP. Frühwirth Michael, Textilarbeiter; Post Horn. Wien-Atzgersdorf. SPÖ. Proksch Anton, Leitender Sekretär Tschadck Otto, Dr., Bundes— des ÖGB.; Wien. SPÖ. Gasmlich Anton, Dr., Professor; Wien, VdU. minister für Justiz; Wien, SPÖ. Rosenberger Paul, Landwirt; Wallner Josef, Holzgroßhändler; DeutschJahrndorf 169. SPÖ. Gindler Anton, Bauer; Perndorf 13, Post Schweiggers. ÖVP. Amstetten, ÖVP. Strobl Franz, Ing., Landes- Widmayer Heinrich, Verwalter; forstdirektor; Wien. ÖVP. Gschweidl Rudolf, Lagerhalter; Puchberg am Schneeberg, Sier— Wien. -

Ed Van De Gevel Trying to Figure out the Rules of a Futuristic Chess Set

No. 143 -(VoJ.IX) ISSN-0012-7671 Copyright ARVES Reprinting of (parts of) this magazine is only permitted for non commercial purposes and with acknowledgement. January 2002 Ed van de Gevel trying to figure out the rules of a futuristic chess set. 493 Editorial Board EG Subscription John Roycroft, 17 New Way Road, London, England NW9 6PL e-mail: [email protected] EG is produced by the Dutch-Flemish Association for Endgame Study Ed van de Gevel, ('Alexander Rueb Vereniging voor Binnen de Veste 36, schaakEindspelStudie') ARVES. Subscrip- 3811 PH Amersfoort, tion to EG is not tied to membership of The Netherlands ARVES. e-mail: [email protected] The annual subscription of EG (Jan. 1 - Dec.31) is EUR 22 for 4 issues. Payments Harold van der Heijden, should be in EUR and can be made by Michel de Klerkstraat 28, bank notes, Eurocheque (please fill in your 7425 DG Deventer, validation or garantee number on the The Netherlands back), postal money order, Eurogiro or . -e-mail: harold van der [email protected] bank cheque. To compensate for bank charges payments via Eurogiro or bank Spotlight-column: cheque should be EUR 27 and EUR 31 Jurgen Fleck, respectively, instead of 22. NeuerWeg 110, Some of the above mentioned methods of D-47803 Krefeld, payment may not longer be valid in 2002! Germany Please inform about this at your bank!! e-mail: juergenlleck^t-online.de All payments can be addressed to the Originals-column: treasurer (see Editorial Board) except those Noam D. Elkies by Eurogiro which should be directed to: Dept of Mathematics, Postbank, accountnumber 54095, in the SCIENCE CENTER name of ARVES, Leiderdorp, The Nether- One Oxford Street, lands. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Dutchman Who Did Not Drink Beer. He Also Surprised My Wife Nina by Showing up with Flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital Just Before She Gave Birth to My Son Mitchell

168 The Bobby Fischer I Knew and Other Stories Dutchman who did not drink beer. He also surprised my wife Nina by showing up with flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital just before she gave birth to my son Mitchell. I hadn't said peep, but he had his quiet ways of finding out. Max was quiet in another way. He never discussed his heroism during the Nazi occupation. Yet not only did he write letters to Alekhine asking the latter to intercede on behalf of the Dutch martyrs, Dr. Gerard Oskam and Salo Landau, he also put his life or at least his liberty on the line for several others. I learned of one instance from Max's friend, Hans Kmoch, the famous in-house annotator at AI Horowitz's Chess Review. Hans was living at the time on Central Park West somewhere in the Eighties. His wife Trudy, a Jew, had constant nightmares about her interrogations and beatings in Holland by the Nazis. Hans had little money, and Trudy spent much of the day in bed screaming. Enter Nina. My wife was working in the New York City welfare system and managed to get them part-time assistance. Hans then confided in me about how Dr. E greased palms and used his in fluence to save Trudy's life by keeping her out of a concentration camp. But mind you, I heard this from Hans, not from Dr. E, who was always Max the mum about his good deeds. Mr. President In 1970, Max Euwe was elected president of FIDE, a position he held until 1978. -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: