How Rebecca Horn Expanded the Boundaries of the Human Body.” Art Basel Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr

Nov 5 Sat 2 :30 PM WILLIAM WEGMAN Nov 26 Sat 2 :30 PM "SHORT STORY VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr . Wegman appeared on the Tonite Show last summer . Now he works at home in his Dave Olive lives in North Liberty, Iowa, own color studio . He will be premiering where he teaches elementary school . videotapes produced at his color studio and at WGBH Boston . JOE DEA "Short Stories" Nov 12 Sat 2 :30 PM KIT FITZGERALD Nov 13 Sun 8 :00 PM JOHN SANBORN Mr . Dea is a cartoonist who works in video . N r "EXCHANGE IN THREE PARTS" He lives in Hartford, Connecticut . recently completed at TV Laboratory at WNET 8 Channel 13 and currently showing in the tenth Dec 3 Sat 2 :30 PM JUAN DOWNEY 2W Bienale du Paris . Dec 4 Sun 8 :00 PM "MORE THAN TWO" QQ An experience in audio video stereo perception cc ~ Kit ON Z Fitzgerald and John Sanborn have been artist and an account of a video expedition to a OY in residence at ZBS Media and the TV Lab of WNET primitive tribe in South America : The Yanomany . cc cc Y Channel 13 and are currently involved in the o 0.0 Cn >- s International TV Workshop . Their work will be ]sec 10 Sat 2 :30 PM MARILYN GOLDSTEIN 9 W3(L W V O broadcast this season over Public TV . "Voice of the Handicapped" 0 W "Video Beats Westway" a 0 HZ a a OW Nov 19 Sat 2 :30 PM STEINA a W= W Nov 20 Sun 8 :00 PM "Snowed-in Tape and Other Work - 1977" Dec 11 Sun 8 :00 PM LYNDA BENGLIS / STANTON KAYE a 0 "How's Tricks?" Z c 0>NH . -

Is Marina Abramović the World's Best-Known Living Artist? She Might

Abrams, Amah-Rose. “Marina Abramovic: A Woman’s World.” Sotheby’s. May 10, 2021 Is Marina Abramović the world’s best-known living artist? She might well be. Starting out in the radical performance art scene in the early 1970s, Abramović went on to take the medium to the masses. Working with her collaborator and partner Ulay through the 1980s and beyond, she developed long durational performance art with a focus on the body, human connection and endurance. In The Lovers, 1998, she and Ulay met in the middle of the Great Wall of China and ended their relationship. For Balkan Baroque, 1997, she scrubbed clean a huge number of cow bones, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for her work. And in The Artist is Present 2010, performed at MoMA in New York, she sat for eight hours a day engaging in prolonged eye contact over three months – it was one of the most popular exhibits in the museum’s history. Since then, she has continued to raise the profile of artists around the world by founding the Marina Abramović Institute, her organisation aimed at expanding the accessibility of time- based work and creating new possibilities for collaboration among thinkers of all fields. MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ / ULAY, THE LOVERS, MARCH–JUNE 1988, A PERFORMANCE THAT TOOK PLACE ACROSS 90 DAYS ON THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA. © MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ AND ULAY, COURTESY: THE MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES / DACS 2021. Fittingly for someone whose work has long engaged with issues around time, Marina Abramović has got her lockdown routine down. She works out, has a leisurely breakfast, works during the day and in the evening, she watches films. -

Mind Over Matter Artforum, Nov, 1996 by Hans-Ulrich Obrist

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_n3_v35/ai_18963443/ Mind over matter ArtForum, Nov, 1996 by Hans-Ulrich Obrist At the Kunsthalle Bern, where Szeemann made his reputation during his eight-year tenure, he organized twelve to fifteen exhibitions a year, turning this venerable institution into a meeting ground for emerging European and American artists. His coup de grace, "When Attitudes Become Form: Live in Your Head," was the first exhibition to bring together post-Minimalist and Conceptual artists in a European institution, and marked a turning point in Szeemann's career - with this show his aesthetic position became increasingly controversial, and due to interference and pressure to adjust his programming from the Kunsthalle's board of directors and Bern's municipal government, he resigned, and set himself up as an Independent curator. If Szeemann succeeded in transforming Bern's Kunsthalle into one of the most dynamic institutions of its time, his 1972 version of Documenta did no less for this art-world staple, held every five years in Kassel, Germany. Conceived as a "100-Day Event," it brought together artists such as Richard Serra, Paul Thek, Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas, and Rebecca Horn, and included not only painting and sculpture but installations, performances, Happenings, and, of course, events that lasted the full 100 days, such as Joseph Beuys' Office for Direct Democracy. Artists have always responded to Szeemann and his approach to curating, which he himself describes as a "structured chaos." Of "Monte Verita," a show mapping the visionary utopias of the early twentieth century, Mario Merz said Szeemann "visualized the chaos we, as artists, have in our heads. -

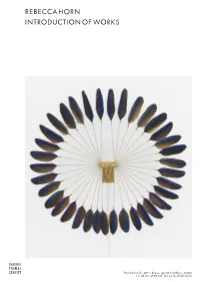

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

Catalogue 234 Jonathan A

Catalogue 234 Jonathan A. Hill Bookseller Art Books, Artists’ Books, Book Arts and Bookworks New York City 2021 JONATHAN A. HILL BOOKSELLER 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10 b New York, New York 10023-8143 home page: www.jonathanahill.com JONATHAN A. HILL mobile: 917-294-2678 e-mail: [email protected] MEGUMI K. HILL mobile: 917-860-4862 e-mail: [email protected] YOSHI HILL mobile: 646-420-4652 e-mail: [email protected] Further illustrations can be seen on our webpage. Member: International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America We accept Master Card, Visa, and American Express. Terms are as usual: Any book returnable within five days of receipt, payment due within thirty days of receipt. Persons ordering for the first time are requested to remit with order, or supply suitable trade references. Residents of New York State should include appropriate sales tax. COVER ILLUSTRATION: © 2020 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York PRINTED IN CHINA 1. ART METROPOLE, bookseller. [From upper cover]: Catalogue No. 5 – Fall 1977: Featuring european Books by Artists. Black & white illus. (some full-page). 47 pp. Large 4to (277 x 205 mm.), pictorial wrap- pers, staple-bound. [Toronto: 1977]. $350.00 A rare and early catalogue issued by Art Metropole, the first large-scale distributors of artists’ books and publications in North America. This catalogue offers dozens of works by European artists such as Abramovic, Beuys, Boltanski, Broodthaers, Buren, Darboven, Dibbets, Ehrenberg, Fil- liou, Fulton, Graham, Rebecca Horn, Hansjörg Mayer, Merz, Nannucci, Polke, Maria Reiche, Rot, Schwitters, Spoerri, Lea Vergine, Vostell, etc. -

Documenta 5 Working Checklist

HARALD SZEEMANN: DOCUMENTA 5 Traveling Exhibition Checklist Please note: This is a working checklist. Dates, titles, media, and dimensions may change. Artwork ICI No. 1 Art & Language Alternate Map for Documenta (Based on Citation A) / Documenta Memorandum (Indexing), 1972 Two-sided poster produced by Art & Language in conjunction with Documenta 5; offset-printed; black-and- white 28.5 x 20 in. (72.5 x 60 cm) Poster credited to Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Ian Burn, Michael Baldwin, Charles Harrison, Harold Hurrrell, Joseph Kosuth, and Mel Ramsden. ICI No. 2 Joseph Beuys aus / from Saltoarte (aka: How the Dictatorship of the Parties Can Overcome), 1975 1 bag and 3 printed elements; The bag was first issued in used by Beuys in several actions and distributed by Beuys at Documenta 5. The bag was reprinted in Spanish by CAYC, Buenos Aires, in a smaller format and distrbuted illegally. Orginally published by Galerie art intermedai, Köln, in 1971, this copy is from the French edition published by POUR. Contains one double sheet with photos from the action "Coyote," "one sheet with photos from the action "Titus / Iphigenia," and one sheet reprinting "Piece 17." 16 ! x 11 " in. (41.5 x 29 cm) ICI No. 3 Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Poster 33 x 23 " in. (84.3 x 60 cm) ICI /Documenta 5 Checklist page 1 of 13 ICI No. 4 Lawrence Weiner A Primer, 1972 Artists' book, letterpress, black-and-white 5 # x 4 in. (14.6 x 10.5 cm) Documenta Catalogue & Guide ICI No. 5 Harald Szeemann, Arnold Bode, Karlheinz Braun, Bazon Brock, Peter Iden, Alexander Kluge, Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Exhibition catalogue, offset-printed, black-and-white & color, featuring a screenprinted cover designed by Edward Ruscha. -

New Title Information Time Pieces

New title information Time Pieces Product Details Video Art since 1963 £19 Artist(s) Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Joseph Beuys, Dara Birnbaum, Cerith Founded in 1971 as an artists’ and cultural producers’ initiative, the Wyn Evans, Valie Export, Harun Farocki, Dan Graham, Gary Hill, Video-Forum, with over 1400 international works, is the oldest Laura Horelli, Rebecca Horn, collection of video art in Germany. Christian Jankowski, Joan Jonas, Imi Knoebel, Daniel Knorr, Oleg Kulik, Focal points of the collection are Fluxus, feminist video, historical and Bjorn Melhus, Bruce Nauman, Marcel contemporary video art from Berlin as well as media-reflective Odenbach, Claes Oldenburg, Tony Oursler, Nam June Paik, Bill Viola, approaches. Key works from the early period of video art are equally Wolf Vostell, Robert Wilson, Ming well represented as current productions. Wong, Haegue Yang, Heimo Zobernig Author(s) Sylvia Arnaout, Marius Babias, This book documents the complete contents of the collection and Kathrin Becker, Dieter Daniels, Gisela includes illustrations, forming a comprehensive compendium of Jo Eckhardt, Sophie Goltz, Tabea international video art for artists, curators and teachers. Metzel, Bert Rebhandl Editor(s) Marius Babias, Kathrin Becker, English and German text. Sophie Goltz Publisher Walther Koenig ISBN 9783863350741 Format softback Pages 456 Illustrations illustrated in b&w Dimensions 230mm x 160mm Weight 930 Publication Date: Dec 2013 Distributed by Enquiries Website Cornerhouse Publications +44 (0)161 212 3466 / 3468 www.cornerhousepublications.org HOME [email protected] 2 Tony Wilson Place Twitter Manchester Orders @CornerhousePubs M15 4FN +44 (0) 1752 202301 England [email protected]. -

Senga Nengudi's Art Within and Without Feminism, Postminimalism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-13-2020 Beyond Movements: Senga Nengudi’s Art Within and Without Feminism, Postminimalism, and the Black Arts Movement Tess Thackara CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/605 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Beyond Movements: Senga Nengudi’s Art Within and Without Feminism, Postminimalism, and the Black Arts Movement by Tess Thackara Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 Thesis Sponsor: May 4, 2020 Dr. Howard Singerman _____________ ______________________ Date Signature May 4, 2020 Dr. Lynda Klich _____________ ______________________ Date Signature Table of Contents List of Illustrations……………………………………………………………………………....ii Introduction……………………………………………………………………….......................1 Chapter 1: “Black Fingerprints and the Fragrance of a Woman”: Senga Nengudi and Feminism………………………………………………………………………………………..12 Chapter 2: Toward Her Own Total Theater: Senga Nengudi and Postminimalism…………….31 Chapter 3: Ritual and Transformation: Senga Nengudi and the Black Arts Movement……………………………………………………………………………………….49 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………64 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………….68 Illustrations……………………………………………………………………………………...72 i List of Illustrations Fig. 1: Senga Nengudi, ACQ series (install view), 2016–7, refrigerator and air conditioner parts, fan, nylon pantyhose, and sand. © Senga Nengudi. Courtesy of the artist, Lévy Gorvy, Thomas Erben Gallery, and Sprüth Magers. Fig. 2: Senga Nengudi, ACQ I, 2016–7, refrigerator and air conditioner parts, fan, nylon pantyhose, and sand. -

The Feminist, Environmental, and Land Art

1971 Rebecca Horn, Moveable Shoulder Extensions (Bewegliche Schulterstäbe) 2017 Antonia Wright, Under the Water Was Sand, The Rocks, Miles of Rocks, Then Fire Adrian Piper, Catalysis IV 2001 – 2002 Ana Teresa Fernández, Of Bodies 1976 Allora & Calzadilla, Land Mark and Borders 1 (performance Ana Mendieta, Untitled, (Foot Prints) #10 documentation) Silueta Series 2019 Saskia Jordá, Radius 1979 1971 – 73 Lotty Rosenfeld, Una milla Eleanor Antin, The Wonder de cruces sobre el pavimento 2006 2015 of It All, from The King of (A mile of crosses on the pavement) Angela Ellsworth, Is This the Place Sarah Cameron Sunde, 36.5 / Solana Beach North Sea, Katwijk Aan Zee, The Netherlands 2010 Maria Hupfield, The One Who Keeps On Giving 1982 Marina Abramovic´, Agnes Denes, Wheatfield— 1976 1980 1997 2001 – 2006 Looking at the Mountains from 1977 Beth Ames Swartz, The Red A Confrontation: Battery Park Francis Alÿs, Paradox of Praxis 1 1973 VALIE EXPORT, Abrundung II Pope.L, The Great White Way: the series Back to Simplicity Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz, Sea #1 (from the series Israel Landfill, Downtown Manhattan— (Sometimes Doing Something 2005 Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing, (Round Off II) 22 miles, 5 years, 1 street 1970 In Mourning and in Rage Revisited, Ten Sites) With New York Financial Center Leads to Nothing) Christian Philipp Müller, 2562 km Tracks, Maintenance: Outside (Segment #1: December 29, 2001) 2013 Bonnie Ora Sherk, Sitting Still II Zhou Tao, After Reality FEATURED ARTWORKS IN COUNTER-LANDSCAPES FEATURED ARTWORKS IN COUNTER-LANDSCAPES 1969 Earth Art February 1969 Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University First American museum to show an exhibition of earth art. -

To Perform the Layered Body—A Short Exploration of the Body in Performance

To Perform the Layered Body—A Short Exploration of the Body in Performance Helena De Preester Ghent University The aim of this article is to focus on the body as instrument or means in performance-art. Since the body is no monolithic given, the body is approached in terms of its constitutive layers, and this may enable us to conceive of the mechanisms that make performances possible and opera- tional, i.e. those bodily mechanisms that are implicitly or explicitly controlled or manipulated in performance. Of course, the exploitation of these bodily layers is not solely responsible for the generation of meaning in performance. Yet, it is that what fundamentally /enables/ the genera- tion of sense and signification in performance-art. To approach the body in terms of its layers, from body image and body schema to in-depth body, may partly answer the complexity at work in art performances, since these concepts enable us to consider, on a theoretical level, the body as represented object, as subject, as motor means for being-in-the-world, as origin of subjectivity and emotions, as hidden but most intimate place of impersonal life processes, as possibly distant image, as sensitive, fragile and plastic entity, as something we own and are owned by, as our most personal and yet extremely strange body. 1. Introduction: philosophy and the explicitness of the body Philosophers are cleanly people when it comes to the body. Although Descartes dissected animal corpses (and at least once had vivisected a rab- bit) in order to satisfy his curiosity for anatomy (Rodis-Lewis, 1995), this philosopher also proclaimed a purified, mechanistic view on bodily func- tioning and movement. -

E-Installation: Synesthetic Documentation of Media Art Via Telepresence Technologies

e-Installation: Synesthetic Documentation of Media Art via Telepresence Technologies Jesús Muñoz Morcilloa*, Florian Faionb [1], Antonio Zeab [2], Uwe D. Hanebeckb [3], Caroline Y. Robertson-von Trothaa [4] a ZAK | Centre for Cultural and General Studies, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Kaiserstr. 12, 76131 Karlsruhe, Germany b Intelligent Sensor-Actuator-Systems Laboratory (ISAS), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Kaiserstr. 12, 76131 Karlsruhe, Germany Keywords: Synesthetic documentation, immersive visualization, media art, telepresence, Nam June Paik, Marc Lee, e-Installation, advanced 3D modeling, art conservation, informational preservation ABSTRACT In this paper, a new synesthetic documentation method that contributes to media art conservation is presented. This new method is called “e-Installation” in analogy to the idea of the “e-Book” as the electronic version of a real book. An e-Installation is a virtualized media artwork that reproduces all synesthesia, interaction, and meaning levels of the artwork. Advanced 3D modeling and telepresence technologies with a very high level of immersion allow the virtual re-enactment of works of media art that are no longer performable or rarely exhibited. The virtual re-enactment of a media artwork can be designed with a scalable level of complexity depending on whether it addresses professionals such as curators, art restorers, and art theorists or the general public. An e-Installation is independent from the artwork’s physical location and can be accessed via head-mounted display or similar data goggles, computer browser, or even mobile devices. In combination with informational and preventive conservation measures, the e-Installation offers an intermediate and long-term solution to archive, disseminate, and pass down the milestones of media art history as a synesthetic documentation when the original work can no longer be repaired or exhibited in its full function. -

Press Release Rebecca Horn. Theatre of Metamorphoses

October 4th, 2018 PRESS RELEASE REBECCA HORN. THEATRE OF METAMORPHOSES From 08.06.19 to 13.01.20 Press contacts Centre Pompidou-Metz Agathe Bataille Head of Publics and Communication 00 33 (0)3 87 15 39 83 email :agathe.bataille@centrepompidou -metz.fr Marion Gales Press relations téléphone : 00 33 (0)3 87 15 52 76 mél :marion.gales@centrepompidou- metz.fr Claudine Colin Communication Pénélope Ponchelet 00 33 (0)1 42 72 60 01 email :[email protected] Crédits : Rebecca Horn The feathered prison Centre Pompidou-Metz and the Museum Tinguely of Basel are fan (Die sanfte Gefangene) 1978 Extrait du film Le Danseur (Der joining together to organise from June 2019 two exhibitions Eintänzer) Daros Collection, Zürich © ADAGP Paris 2018 devoted to Rebecca Horn (born in 1944 in Michelstadt, in Germany): Theatre of Metamorphoses in Metz and Body Fantasies in Basel. Presented simultaneously, the exhibitions explore the process of metamorphoses, in turns animal, mannerist and cinematic in Metz and machine like or kinetic in Basel. They offer complementary major perspectives on the work of one of the most singular artists of her generation, of which certain parts of her work are still unsung. 1 The exhibition Rebecca Horn. Theatre of Metamorphoses at Centre Pompidou-Metz highlights the extraordinary range of forms of expression which the artist employs. It will also underline the role of creative influence that her cinematic work has had, a true theatralisation of her works supported by a liberating and anarchic energy where poetry and humour are at the heart of the subject. The project goes back over the subtle dialogue linking the works of five decades of creation.