To Perform the Layered Body—A Short Exploration of the Body in Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020 James MacDevitt, M.A. Associate Professor of Art History and Visual & Cultural Studies Director, Cerritos College Art Gallery Department of Art and Design Fine Arts and Communications Division Cerritos College January 2021 Table of Contents Title Page i Table of Contents ii Sabbatical Leave Application iii Statement of Purpose 35 Objectives and Outcomes 36 OER Textbook: Disciplinary Entanglements 36 Getty PST Art x Science x LA Research Grant Application 37 Conference Presentation: Just Futures 38 Academic Publication: Algorithmic Culture 38 Service and Practical Application 39 Concluding Statement 40 Appendix List (A-E) 41 A. Disciplinary Entanglements | Table of Contents 42 B. Disciplinary Entanglements | Screenshots 70 C. Getty PST Art x Science x LA | Research Grant Application 78 D. Algorithmic Culture | Book and Chapter Details 101 E. Just Futures | Conference and Presentation Details 103 2 SABBATICAL LEAVE APPLICATION TO: Dr. Rick Miranda, Jr., Vice President of Academic Affairs FROM: James MacDevitt, Associate Professor of Visual & Cultural Studies DATE: October 30, 2018 SUBJECT: Request for Sabbatical Leave for the 2019-20 School Year I. REQUEST FOR SABBATICAL LEAVE. I am requesting a 100% sabbatical leave for the 2019-2020 academic year. Employed as a fulltime faculty member at Cerritos College since August 2005, I have never requested sabbatical leave during the past thirteen years of service. II. PURPOSE OF LEAVE Scientific advancements and technological capabilities, most notably within the last few decades, have evolved at ever-accelerating rates. Artists, like everyone else, now live in a contemporary world completely restructured by recent phenomena such as satellite imagery, augmented reality, digital surveillance, mass extinctions, artificial intelligence, prosthetic limbs, climate change, big data, genetic modification, drone warfare, biometrics, computer viruses, and social media (and that’s by no means meant to be an all-inclusive list). -

VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr

Nov 5 Sat 2 :30 PM WILLIAM WEGMAN Nov 26 Sat 2 :30 PM "SHORT STORY VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr . Wegman appeared on the Tonite Show last summer . Now he works at home in his Dave Olive lives in North Liberty, Iowa, own color studio . He will be premiering where he teaches elementary school . videotapes produced at his color studio and at WGBH Boston . JOE DEA "Short Stories" Nov 12 Sat 2 :30 PM KIT FITZGERALD Nov 13 Sun 8 :00 PM JOHN SANBORN Mr . Dea is a cartoonist who works in video . N r "EXCHANGE IN THREE PARTS" He lives in Hartford, Connecticut . recently completed at TV Laboratory at WNET 8 Channel 13 and currently showing in the tenth Dec 3 Sat 2 :30 PM JUAN DOWNEY 2W Bienale du Paris . Dec 4 Sun 8 :00 PM "MORE THAN TWO" QQ An experience in audio video stereo perception cc ~ Kit ON Z Fitzgerald and John Sanborn have been artist and an account of a video expedition to a OY in residence at ZBS Media and the TV Lab of WNET primitive tribe in South America : The Yanomany . cc cc Y Channel 13 and are currently involved in the o 0.0 Cn >- s International TV Workshop . Their work will be ]sec 10 Sat 2 :30 PM MARILYN GOLDSTEIN 9 W3(L W V O broadcast this season over Public TV . "Voice of the Handicapped" 0 W "Video Beats Westway" a 0 HZ a a OW Nov 19 Sat 2 :30 PM STEINA a W= W Nov 20 Sun 8 :00 PM "Snowed-in Tape and Other Work - 1977" Dec 11 Sun 8 :00 PM LYNDA BENGLIS / STANTON KAYE a 0 "How's Tricks?" Z c 0>NH . -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

The New York Times, Who Is Valie Export

http://nyti.ms/299CwWZ ART & DESIGN Who Is Valie Export? Just Look, and Please Touch By RANDY KENNEDY JUNE 29, 2016 In 1967, the Austrian artist Waltraud Hollinger jettisoned her family name and the last name her husband had given her and became Valie Export, a nom de guerre inspired by a popular brand of cigarettes. But late last week, at a hotel in the West Village where she was supposed to be staying, the front desk could find no record of a Valie Export having checked in. Marieluise Hessel, the art collector and benefactor of the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. — which has just opened a show built around Ms. Export’s highly influential work — stared worriedly into the screen on her phone. “I checked her Wikipedia page,” she said. “I asked under her maiden name and her married name. She must be somewhere else.” But just then, Ms. Export, wearing a long translucent white jacket and fashionable tennis shoes, her hair dyed copper red, emerged from the elevator. Explaining her spectral existence, at least as far as hotel registers were concerned, she rolled her eyes. “I used to have Valie Export on my passport — for years,” she said. “Now I have to use my name with my second husband. Something about security, I guess. Can you believe it?” The comedy of the situation was not lost on her. Ms. Export’s performances and films were among the most radical feminist statements in Europe in the 1960s and 1970s, and her work, through feminism, delved deeply into systems of control that have become omnipresent in the 21st century: surveillance, information as power, unseen political machinations. -

Is Marina Abramović the World's Best-Known Living Artist? She Might

Abrams, Amah-Rose. “Marina Abramovic: A Woman’s World.” Sotheby’s. May 10, 2021 Is Marina Abramović the world’s best-known living artist? She might well be. Starting out in the radical performance art scene in the early 1970s, Abramović went on to take the medium to the masses. Working with her collaborator and partner Ulay through the 1980s and beyond, she developed long durational performance art with a focus on the body, human connection and endurance. In The Lovers, 1998, she and Ulay met in the middle of the Great Wall of China and ended their relationship. For Balkan Baroque, 1997, she scrubbed clean a huge number of cow bones, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for her work. And in The Artist is Present 2010, performed at MoMA in New York, she sat for eight hours a day engaging in prolonged eye contact over three months – it was one of the most popular exhibits in the museum’s history. Since then, she has continued to raise the profile of artists around the world by founding the Marina Abramović Institute, her organisation aimed at expanding the accessibility of time- based work and creating new possibilities for collaboration among thinkers of all fields. MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ / ULAY, THE LOVERS, MARCH–JUNE 1988, A PERFORMANCE THAT TOOK PLACE ACROSS 90 DAYS ON THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA. © MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ AND ULAY, COURTESY: THE MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES / DACS 2021. Fittingly for someone whose work has long engaged with issues around time, Marina Abramović has got her lockdown routine down. She works out, has a leisurely breakfast, works during the day and in the evening, she watches films. -

The Estate of General Idea: Ziggurat, 2017, Courtesy of Mitchell-Innes and Nash

Installation view of The Estate of General Idea: Ziggurat, 2017, Courtesy of Mitchell-Innes and Nash. © General Idea. The Estate of General Idea (1969-1994) had their first exhibition with the Mitchell-Innes & Nash Gallery on view in Chelsea through January 13, featuring several “ziggurat” paintings from the late 1960s, alongside works on paper, photographs and ephemera that highlight the central importance of the ziggurat form in the rich practice of General Idea. It got me thinking about the unique Canadian trio’s sumptuous praxis and how it evolved from humble roots in the underground of the early 1970s to its sophisticated position atop the contemporary art world of today. One could say that the ziggurat form is a perfect metaphor for a staircase of their own making that they ascended with grace and elegance, which is true. But they also had to aggressively lacerate and burn their way to the top, armed with real fire, an acerbic wit and a penchant for knowing where to apply pressure. Even the tragic loss of two thirds of their members along the way did not deter their rise, making the unlikely climb all the more heroic. General Idea, VB Gown from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pageant, Urban Armour for the Future, 1975, Gelatin Silver Print, 10 by 8 in. 25.4 by 20.3 cm, Courtesy Mitchell-Innes and Nash. © General Idea. The ancient architectural structure of steps leading up to a temple symbolizes a link between humans and the gods and can be found in cultures ranging from Mesopotamia to the Aztecs to the Navajos. -

Crossing Into Eighties Overview 2012

Crown Point Press Newsletter June 2012 The waterfall on Ponape, clockwise from front: Dorothy Wiley, Marina Abramovic, Joan Jonas, Daniel Buren, Chris Burden, and Mary Corse, 1980. Tom Marioni had named the conference “Word of Mouth” VISION #4. Twelve artists each gave a twelve-minute talk. Since LP records lasted twenty-four minutes, he had specified twelve-minute talks so we could put two on a side. Later we presented three records in a box. The records are white—“because it felt like we were landing from a flying saucer when we got off the plane in Ponape,” Tom remembers. The plane circled over what looked like a green dot in a blue sea, and we landed abruptly on a short white runway made of crushed coral with a great green rocky cliff at one end and the sea at the other. Against the cliff was a new low building. Shirtless workers in jeans hustled our bags from the plane into a big square hole in the building’s side, visibly pushing them onto a moving carousel. A man in a grass skirt and an inspector’s cap hustled us inside to claim them. The airport building was full of people, many in grass skirts, some (men and women) topless. CrOSSINg INTO THE EIgHTIES They clapped and whistled as we filed past. We learned later Escape Now and Again that word had circulated that we were an American rock group. In front of the airport was a flatbed truck with fourteen An excerpt from a memoir in progress by Kathan Brown white wicker chairs from the hotel dining room strapped On January 15, 1980, thirty-five artists and other art people, on the bed in two facing rows. -

Art and Vinyl — Artist Covers and Records Komposition René Pulfer Kuratoren: Søren Grammel, Philipp Selzer 17

Art and Vinyl — Artist Covers and Records Komposition René Pulfer Kuratoren: Søren Grammel, Philipp Selzer 17. November 2018 – 03. Februar 2019 Ausstellungsinformation Raumplan Wand 3 Wand 7 Wand 2 Wand 6 Wand 5 Wand 4 Wand 2 Wand 1 ARTIST WORKS for 33 1/3 and 45 rpm (revolutions per minute) Komposition René Pulfer Der Basler Künstler René Pulfer, einer der Pioniere der Schweizer Videokunst und Hochschulprofessor an der HGK Basel /FHNW bis 2015, hat sich seit den späten 1970 Jahren auch intensiv mit Sound Art, Kunst im Kontext von Musik (Covers, Booklets, Artist Editions in Mu- sic) interessiert und exemplarische Arbeiten von Künstlerinnen und Künstlern gesammelt. Die Ausstellung konzentriert sich auf Covers und Objekte, bei denen das künstlerische Bild in Form von Zeichnung, Malerei oder Fotografie im Vordergrund steht. Durch die eigenständige Präsenz der Bildwerke treten die üblichen Angaben zur musikalischen und künstlerischen Autorschaft in den Hintergrund. Die Sammlung umfasst historische und aktuelle Beispiele aus einem Zeitraum von über 50 Jahren mit geschichtlich unterschiedlich gewachsenen Kooperationsformen zwischen Kunst und Musik bis zu aktuellen Formen der Multimedialität mit fliessenden Grenzen, so wie bei Rodney Graham mit der offenen Fragestellung: „Am I a musician trapped in an artist's mind or an artist trapped in a musician's body?" ARTIST WORKS for 33 1/3 and 45 rpm (revolutions per minute) Composition René Pulfer The Basel-based artist René Pulfer, one of the pioneers of Swiss video- art and a university professor at the HGK Basel / FHNW until 2015, has been intensively involved with sound art in the context of music since the late 1970s (covers, booklets, artist editions in music ) and coll- ected exemplary works by artists. -

I – Introduction

QUEERING PERFORMATIVITY: THROUGH THE WORKS OF ANDY WARHOL AND PERFORMANCE ART by Claudia Martins Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2008 I never fall apart, because I never fall together. Andy Warhol The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back again CEU eTD Collection CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER 1 - Introduction .............................................................................................7 CHAPTER 2 - Bringing the body into focus...................................................................13 CHAPTER 3 - XXI century: Era of (dis)embodiment......................................................17 Disembodiment in Virtual Spaces ..........................................................18 Embodiment Through Body Modification................................................19 CHAPTER 4 - Subculture: Resisting Ajustment ............................................................22 CHAPTER 5 - Sexually Deviant Bodies........................................................................24 CHAPTER 6 - Performing gender.................................................................................29 -

Mind Over Matter Artforum, Nov, 1996 by Hans-Ulrich Obrist

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_n3_v35/ai_18963443/ Mind over matter ArtForum, Nov, 1996 by Hans-Ulrich Obrist At the Kunsthalle Bern, where Szeemann made his reputation during his eight-year tenure, he organized twelve to fifteen exhibitions a year, turning this venerable institution into a meeting ground for emerging European and American artists. His coup de grace, "When Attitudes Become Form: Live in Your Head," was the first exhibition to bring together post-Minimalist and Conceptual artists in a European institution, and marked a turning point in Szeemann's career - with this show his aesthetic position became increasingly controversial, and due to interference and pressure to adjust his programming from the Kunsthalle's board of directors and Bern's municipal government, he resigned, and set himself up as an Independent curator. If Szeemann succeeded in transforming Bern's Kunsthalle into one of the most dynamic institutions of its time, his 1972 version of Documenta did no less for this art-world staple, held every five years in Kassel, Germany. Conceived as a "100-Day Event," it brought together artists such as Richard Serra, Paul Thek, Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas, and Rebecca Horn, and included not only painting and sculpture but installations, performances, Happenings, and, of course, events that lasted the full 100 days, such as Joseph Beuys' Office for Direct Democracy. Artists have always responded to Szeemann and his approach to curating, which he himself describes as a "structured chaos." Of "Monte Verita," a show mapping the visionary utopias of the early twentieth century, Mario Merz said Szeemann "visualized the chaos we, as artists, have in our heads. -

MANGAARD C.V 2019 (6Pg)

ANNETTE MANGAARD Film/Video/Installation/Photography Born: Lille Værløse, Denmark. Canadian Citizen Education: MFA, Gold Medal Award, OCAD University 2017 BIO Annette Mangaard is a Danish born Canadian media artist and filmmaker who has recently completed her Masters in Interdisciplinary Art, Media and Design. Her installation work has been shown around the world including: the Armoury Gallery, Olympic Site in Sydney Australia; Pearson International Airport, Toronto; South-on Sea, Liverpool and Manchester, UK; Universidad Nacional de Río Negro, Patagonia, Argentina; and Whitefish Lake, First Nations, Ontario. Mangaard has completed more then 16 films in more than a decade as an independent filmmaker. Her feature length experimental documentary on photographer Suzy Lake and the history of feminism screened as part of the INTRODUCING SUZY LAKE exhibition October 2014 through March 2015 at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Mangaard was nominated for a Gemini for Best Director of a Documentary for her one hour documentary, GENERAL IDEA: ART, AIDS, AND THE FIN DE SIECLE about the celebrated Canadian artists collective which premiered at Hot Doc’s in Toronto then went on to garner accolades around the world. Mangaard’s one hour documentary KINNGAIT: RIDING LIGHT INTO THE WORLD, about the changing face of the Inuit artists of Cape Dorset premiered at the Art Gallery of Ontario and was invited to Australia for a special screening celebrating Canada Day with the Canadian High Commission. Mangaard’s body of work was presented as a retrospective at the Palais de Glace, Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2009 and at the PAFID, Patagonia, Argentina in 2013. In 1990 Mangaard was invited to present solo screenings of her films at the Pacific Cinematheque in Vancouver, Canada and in 1991 at the Kino Arsenal Cinematheque in Berlin, West Germany. -

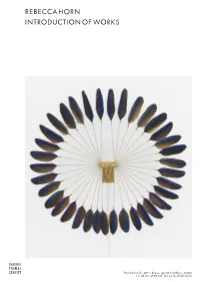

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017).