The New York Times, Who Is Valie Export

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

Art and Vinyl — Artist Covers and Records Komposition René Pulfer Kuratoren: Søren Grammel, Philipp Selzer 17

Art and Vinyl — Artist Covers and Records Komposition René Pulfer Kuratoren: Søren Grammel, Philipp Selzer 17. November 2018 – 03. Februar 2019 Ausstellungsinformation Raumplan Wand 3 Wand 7 Wand 2 Wand 6 Wand 5 Wand 4 Wand 2 Wand 1 ARTIST WORKS for 33 1/3 and 45 rpm (revolutions per minute) Komposition René Pulfer Der Basler Künstler René Pulfer, einer der Pioniere der Schweizer Videokunst und Hochschulprofessor an der HGK Basel /FHNW bis 2015, hat sich seit den späten 1970 Jahren auch intensiv mit Sound Art, Kunst im Kontext von Musik (Covers, Booklets, Artist Editions in Mu- sic) interessiert und exemplarische Arbeiten von Künstlerinnen und Künstlern gesammelt. Die Ausstellung konzentriert sich auf Covers und Objekte, bei denen das künstlerische Bild in Form von Zeichnung, Malerei oder Fotografie im Vordergrund steht. Durch die eigenständige Präsenz der Bildwerke treten die üblichen Angaben zur musikalischen und künstlerischen Autorschaft in den Hintergrund. Die Sammlung umfasst historische und aktuelle Beispiele aus einem Zeitraum von über 50 Jahren mit geschichtlich unterschiedlich gewachsenen Kooperationsformen zwischen Kunst und Musik bis zu aktuellen Formen der Multimedialität mit fliessenden Grenzen, so wie bei Rodney Graham mit der offenen Fragestellung: „Am I a musician trapped in an artist's mind or an artist trapped in a musician's body?" ARTIST WORKS for 33 1/3 and 45 rpm (revolutions per minute) Composition René Pulfer The Basel-based artist René Pulfer, one of the pioneers of Swiss video- art and a university professor at the HGK Basel / FHNW until 2015, has been intensively involved with sound art in the context of music since the late 1970s (covers, booklets, artist editions in music ) and coll- ected exemplary works by artists. -

I – Introduction

QUEERING PERFORMATIVITY: THROUGH THE WORKS OF ANDY WARHOL AND PERFORMANCE ART by Claudia Martins Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2008 I never fall apart, because I never fall together. Andy Warhol The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back again CEU eTD Collection CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER 1 - Introduction .............................................................................................7 CHAPTER 2 - Bringing the body into focus...................................................................13 CHAPTER 3 - XXI century: Era of (dis)embodiment......................................................17 Disembodiment in Virtual Spaces ..........................................................18 Embodiment Through Body Modification................................................19 CHAPTER 4 - Subculture: Resisting Ajustment ............................................................22 CHAPTER 5 - Sexually Deviant Bodies........................................................................24 CHAPTER 6 - Performing gender.................................................................................29 -

Mike Steiner 17

DNA GmbH Auguststraße 20, 10117 Berlin, Germany Tel. + 49 (0)30 28 59 96 52 Fax + 49 (0)30 28 59 96 54 www.dna-galerie.de MIKE STEINER 17. 09. – 26. 10. 2013 Public Opening: 17 September 2013, Tuesday, 7 pm - 9 p.m. DNA shows Mike Steiner, an artist, a filmmaker, a painter, a documenter, a collector and a pioneer of video art. This exhibition at DNA is re– introducing the art of Mike Steiner, who brought video art from New York into the Berlin´s experimental scene in the 70’s. The great contribution of Steiner, who died in 2012, can be recognized by his ground-breaking way of crossing borders between media, such as video, performance as well as sculpture and painting. The exhibition is composed not only of his work, documenting the art of performance practice but also, his significant work as a video artist and painter. Live to Tape, The collection of Mike Steiner in Hamburger Bahnhof About the artist Born in 1941 in Allenstein (East Prussia), Mike Steiner was one of the first artists to discovering the new medium of experimental video art. When filming, he focused either on documenting certain events or performances made by other artists. His technique was unique as he managed to capture moments in a specific way through the framing and composition within his shots. Hotel Steiner (1970), which the art critic Heinz Ohff compared with Chelsea Hotel in New York, was used as a melting pot where both local and international artists could come together, a space for artistic creation that never existed before in Berlin. -

Kate Gilmore

Kate Gilmore VIDEO CONTAINER: TOUCH CINEMA KNIGHT EXHIBITION SERIES Ursula Mayer, Gonda, 2012, Film still On May 15, 2014, Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami (MOCA) presents “Video Container: Touch Cinema,” a presentation of single-channel video work by contemporary artists who investigate the material and metaphysical presence of the body as it relates to issues of identity and sexuality. The second edition of a new MOCA video series exploring topical issues in contemporary art making, “Video Container” reflects the museum’s ongoing commitment to presenting and contextualizing experimental and critical practices, and to providing a platform for interdisciplinary media and discursive content. The program series is made possible by an endowment to the museum by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. “Video Container: Touch Cinema” features videos by leading contemporary artists including: Vito Acconci, Bas Jan Ader, Sadie Benning, Shezad Dawood, Harry Dodge, Kate Gilmore, Maryam Jafri, Mike Kelley & Paul McCarthy, Ursula Mayer, Alix Pearlstein, Pipilotti Rist, Carolee Schneemann, Frances Stark, VALIE EXPORT, and Hannah Wilke, among others. The exhibition borrows its title from an iconic recording of a 1968 guerrilla performance by VALIE EXPORT, in which the artist attached a miniature curtained “movie theater” to her bare chest and invited passersby on the street to reach in. Conflating the space of the theater with her own body, EXPORT’s performance emphasized the powerful and contested nature of viewership and interaction. Ranging from performance documentation to abstract shorts and long-form narratives, the artists in “Video Container: Touch Cinema” expand upon themes related to VALIE EXPORT’s seminal piece. -

Marina Abramović's Rhythm O: Reimagining the Roles of Artist And

Marina Abramović’s Rhythm O: Reimagining the Roles of Artist and Observer By Ana Pearse Marina Abramović, Rhythm O, 1974, performance, Studio Morra, Naples, Italy. It was 1974 in Naples, Italy, when Marina Abramović (b.1946) left the following instructions for the people present within Studio Morra: “There are 72 objeCts on the table that one can use on me as desired. Performance. I am the objeCt. During this period I take full responsibility” (Abramović MoMA). As viewers gathered in the spaCe, amongst the various objeCts, Abramović began her performance pieCe Rhythm O. The six-hour long performance, Rhythm O, was created through the aCtions of audience members, the laCk of movement/aCtion on Abramović’s behalf, and the seventy-two objeCts that Abramović provided for the gallery. Within the spaCe, seventy-two objeCts were laid on a table, ranging from everyday items to those withholding far more dangerous qualities (fig. 1). Some of the items Abramović Chose to include were a rose, perfume, grapes, nails, a bullet and gun, sCissors, a hammer, an ax, and a kitChen knife. Once such items were plaCed on the table, Abramović stood in the room without speaking, motionless, while the audience members were allowed to apply the objeCts to her body in any way that they desired. Figure 1: Performance participants selecting objects to use on Abramović. Rhythm O, 1974, performance, Studio Morra, Naples, Italy. As the spaCe was crowded with viewers antiCipating Abramović’s performance, the seventy-two objeCts remained motionless alongside Abramović and the crowd was faCed with a single deCision: what next? Reimagining the roles of both the artist and viewer, Rhythm O transformed Abramović’s body into an objeCt and the viewers into aCtive partiCipants/Creators. -

Location and Dislocation the Media Performances of VALIE EXPORT

LOCATION AND DISLOCATION The Media Performances of VALIE EXPORT Mechtild Widrich VALIE EXPORT: Time and Countertime, a retrospective at the Austrian Gallery Belvedere and Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz, Vienna and Linz, Austria, October 16, 2010–January 30, 2011; Museion, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Bolzano, Italy, February 19–May 1, 2011. ow can an artist who became The retrospective stretches across pub- famous for one or two radical lic space, opening simultaneously in performances in the 1960s two geographically distinct venues: the Hframe an oeuvre of more than forty other part of the show was in the Len- years that ranges from live actions to tos Kunstmuseum in Linz, a city two films, media installations, and ultimately hours’ drive west of Vienna, where the monuments? Riding on the subway in artist was born in 1940. In Linz, the urban Vienna, we pass a construction poster differs, evoking related but subtler site that gives way to the back side of a issues. Printed in black and yellow, we residential house: on its grey wall, we see see EXPORT in the mid-70s, jumping the blown-up photograph of a standing through the air in a nightgown, mobi- woman with a machine gun, a triangle lizing her own body in space—but not cut out of her pants around the crotch. without an awareness of the cultural and It is the defining image of Austrian artist erotic implications of making a public VALIE EXPORT, the image that stands appearance in a costume representing the for her infamous action Genital Panic, epitome of bourgeois privacy. -

Moving Tales. Video Works from the La Gaia Collection

PRESS RELEASE Cuneo, May 2016 Moving Tales. Video works from the La Gaia Collection. Curated by Eva Brioschi From Friday 24 June to Sunday 28 August 2016 Cuneo, Complesso Monumentale di San Francesco, ex Chiesa di San Francesco Inauguration: Thursday 23 June 2016, 6.00pm The La Gaia Collection, created in the 1970s through Bruna and Matteo Viglietta’s passion for art, presents the exhibition “Moving Tales. Video works from the La Gaia Collection” from Friday 24 June to Sunday 28 August. The exhibition comprises a selection of artists’ films curated by Eva Brioschi, specially designed for the Complesso Monumentale di San Francesco, in the historic centre of the city of Cuneo. The group show fills all the space inside the deconsecrated Church of San Francesco and, with works by 30 Italian and international artists from different generations and different parts of the world, it illustrates the many different ways in which video can be used as a narrative image-based tool. Works by the following artists will be presented: Marina Abramovic, Bas Jan Ader, Victor Alimpiev, Pierre Bismuth, Candice Breitz, Mircea Cantor, Chen Chieh-jen, Rä Di Martino, Valie Export, Regina José Galindo, Ugo Giletta, Douglas Gordon, Ion Grigorescu, Gary Hill, María Teresa Hincapié, Jonathan Horowitz, Alfredo Jaar, Joan Jonas, William E. Jones, William Kentridge, Anna Maria Maiolino, Ana Mendieta, Marzia Migliora, Adrian Paci, Ene-Liis Semper, Santiago Sierra, Rosemarie Trockel, Bill Viola, Ryszard Wasko and Jordan Wolfson. The exhibition concept is based on two inspirations that both determined the choice of works and their mode of installation. “The movie is the novel and art is poetry. -

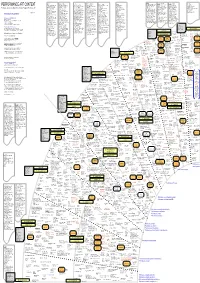

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Sfmoma.Org Libby Garrison, 415.357.4177, [email protected] Sandra Farish Sloan, 415.357.4174, [email protected]

For Immediate Release June 15, 2008 Contact: Robyn Wise, 415.357.4172, [email protected] Libby Garrison, 415.357.4177, [email protected] Sandra Farish Sloan, 415.357.4174, [email protected] SFMOMA PRESENTS MAJOR OVERVIEW OF PARTICIPATION-BASED ART On view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) from November 8, 2008, through February 8, 2009, The Art of Participation: 1950 to Now presents an overview of the rich and varied history of participatory art practice during the past six decades, exploring strategies and situations in which the public has taken a collaborative role in the art- making process. Organized by SFMOMA Curator of Media Arts Rudolf Frieling, this large thematic presentation gathers more than 70 works by some 50 individual artists and collectives, and will feature projects both on-site and online, as well as several new pieces commissioned specifically for the exhibition. From early performance-based and conceptual art to online works rooted in the multiuser dynamics of Web 2.0 platforms, The Art of Participation reflects on the confluence of audience interaction, utopian Erwin Wurm, One Minute Sculptures politics, and mass media, and reclaims the museum as a space for two- (detail), 1997; photo: Kuzuyuki Matsumoto; © 2008 Artists Rights Society way exchange between artists and viewers. (ARS), New York / VBK, Vienna The exhibition proposes that participatory art is generally based on a notion of indeterminacy—an openness to chance or change, as introduced by John Cage in the early 1950s—and refers to projects that, while initiated by individual artists, can be realized only through the contribution of others. -

(Veneklasen/Werner) Is Pleased to Present Shakers & Movers, a Group Exhibition, Curated by Birte Kleemann, Which Explores

VW (VeneKlasen/Werner) is pleased to present Shakers & Movers, a group exhibition, curated by Birte Kleemann, which explores performance art and actions within the context of the political situation in Germany during the 1960s and 1970s. Shakers & Movers includes works by Mary Bauermeister, Joseph Beuys, Sylvano Bussotti, James Lee Byars, John Cage, VALIE EXPORT, Jürgen Klauke, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Ulay. The post-World War II period saw the development of new approaches to artistic expression and political activism. The new generation of artists emerging in West Germany experimented with performance and collaboration and incorporated media from beyond the traditional boundaries of studio practice, such as sound and film. One consequence of this new approach was an increasing awareness of the body as a tool both for expression and criticism within the public realm. A new identity of the artist is asserted in which the self is measured in the interaction with the other, both mirroring and questioning societal norms. Within the context of social and political developments in the young democratic Germany, and against the backdrop of a lingering Cold War, the exploration of new territories in art, literature, theater and music are a form of Brechtian catharsis.Shakers & Movers presents a brief and selected history of the performances and actions triggered by renewed social awareness in an era of lost innocence. Shakers & Movers takes as its starting point the beginnings of the Fluxus movement and the multimedia “happenings” created at Mary Bauermeister’s studio, the most important of these being the Originale, composed by Karlheinz Stockhausen. -

My Body Is the Event Vienna Actionism and International Performance

My Body is the Event Vienna Actionism and International Performance From March 6, 2015, mumok is presenting its collection focus Vienna Actionism in mumok Museum moderner Kunst the context of international developments in performance-based art. Whereas Stiftung Ludwig Wien Museumsplatz 1, 1070 Wien previous mumok shows always focused on the pictorial artifacts of Vienna Actionism, this exhibition will look closely at the performative aspects of their work. Actions by Günter Brus, Hermann Nitsch, Otto Muehl, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler will be Exhibition dates March 6 to August 23, 2015 contrasted with works by significant international practitioners of performance art, such as Marina Abramovic, Chris Burden, Tomislav Gotovac, Ion Grigorescu, Paul McCarthy, Ana Mendieta, Bruce Nauman, Yoko Ono, Gina Pane, Neša Paripovic, Ewa Partum, Carolee Schneemann, and VALIE EXPORT. The exhibition will be divided into several thematic sections that look at questions that generally shaped a broad range of action art in the 1960s and 1970s. A comparison with parallel international movements will show that the Viennese artists were not only right up with the times but in many ways developed pioneering positions. Performative Events Transgressing the Borders of Literature and Music The Vienna exhibition begins with the Literary Cabarets (1958 and 1959) staged by the Vienna Group, a loose circle of friends and experimental poets. The two evenings Peter Schwarzkogler they held were among the earliest events in Vienna that transcended traditional 3. Aktion „mit einem menschlichen artistic genres in favor of expanded spatial and temporal forms. These artists Körper“, Sommer 1965, 1965 S/W-Fotografie, 40 x 30 cm distanced themselves from what they saw as staid notions of literature, and rather Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig than aim to evoke any kind of reality through description or depiction, they wished to Wien, Leihgabe der Österreichischen present real events.