Performance Art and the Prosthetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr

Nov 5 Sat 2 :30 PM WILLIAM WEGMAN Nov 26 Sat 2 :30 PM "SHORT STORY VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr . Wegman appeared on the Tonite Show last summer . Now he works at home in his Dave Olive lives in North Liberty, Iowa, own color studio . He will be premiering where he teaches elementary school . videotapes produced at his color studio and at WGBH Boston . JOE DEA "Short Stories" Nov 12 Sat 2 :30 PM KIT FITZGERALD Nov 13 Sun 8 :00 PM JOHN SANBORN Mr . Dea is a cartoonist who works in video . N r "EXCHANGE IN THREE PARTS" He lives in Hartford, Connecticut . recently completed at TV Laboratory at WNET 8 Channel 13 and currently showing in the tenth Dec 3 Sat 2 :30 PM JUAN DOWNEY 2W Bienale du Paris . Dec 4 Sun 8 :00 PM "MORE THAN TWO" QQ An experience in audio video stereo perception cc ~ Kit ON Z Fitzgerald and John Sanborn have been artist and an account of a video expedition to a OY in residence at ZBS Media and the TV Lab of WNET primitive tribe in South America : The Yanomany . cc cc Y Channel 13 and are currently involved in the o 0.0 Cn >- s International TV Workshop . Their work will be ]sec 10 Sat 2 :30 PM MARILYN GOLDSTEIN 9 W3(L W V O broadcast this season over Public TV . "Voice of the Handicapped" 0 W "Video Beats Westway" a 0 HZ a a OW Nov 19 Sat 2 :30 PM STEINA a W= W Nov 20 Sun 8 :00 PM "Snowed-in Tape and Other Work - 1977" Dec 11 Sun 8 :00 PM LYNDA BENGLIS / STANTON KAYE a 0 "How's Tricks?" Z c 0>NH . -

VIDEO and ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM Hermine Freed

VIDEO AND ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM Hermine Freed If the content of formalist art is form, then the forms in a video whereas others view us through our behavior. Through video, art work are a function of its content. Just as formal similari- we can view our behavior and personal interactions removed ties can be found in minimalist sculptures or abstract expres- from immediate feelings and experiences . Laing speaks of the sionist paintings, videotapes tend to be stylistically unique, ego boundary as the extension between man and society. The although there are likely to be conceptual similarities amongst works of Acconci, Benglis, Campus, Holt, Jonas, Morris, Nau- them. These similarities often arise out of inherent qualities in man, Serra and myself operate on that boundary line. the medium which impress different artists simultaneously . If Peter Campus and Bruce Nauman have both made live minimalist sculptors have explored the nature of the sculptural video installations which involve the viewer directly. In Cam- object, then video artists tend to explore the nature of the pus' Shadow Projection the viewer sees himself projected on a video image. As the range of possibilities is broad, so are the screen from behind with a shadow of his image superimposed sources, ideas, images, techniques, and intentions. Neverthe- over the enlarged color image. He stands between the screen less, similarities can be found in tapes of artists as seemingly and the camera (the interface between seer and seen), turns to dissimilar as Campus, Nauman, and Holt, and some of those see himself, and is frustrated because he is confronted with the similarities can be related to their (unintentional) resemblance camera and can never see his image from the front. -

Resource What Is Modern and Contemporary Art

WHAT IS– – Modern and Contemporary Art ––– – –––– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ––– – – – – ? www.imma.ie T. 00 353 1 612 9900 F. 00 353 1 612 9999 E. [email protected] Royal Hospital, Military Rd, Kilmainham, Dublin 8 Ireland Education and Community Programmes, Irish Museum of Modern Art, IMMA THE WHAT IS– – IMMA Talks Series – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ? There is a growing interest in Contemporary Art, yet the ideas and theo- retical frameworks which inform its practice can be complex and difficult to access. By focusing on a number of key headings, such as Conceptual Art, Installation Art and Performance Art, this series of talks is intended to provide a broad overview of some of the central themes and directions in Modern and Contemporary Art. This series represents a response to a number of challenges. Firstly, the 03 inherent problems and contradictions that arise when attempting to outline or summarise the wide-ranging, constantly changing and contested spheres of both art theory and practice, and secondly, the use of summary terms to describe a range of practices, many of which emerged in opposition to such totalising tendencies. CONTENTS Taking these challenges into account, this talks series offers a range of perspectives, drawing on expertise and experience from lecturers, artists, curators and critical writers and is neither definitive nor exhaustive. The inten- What is __? talks series page 03 tion is to provide background and contextual information about the art and Introduction: Modern and Contemporary Art page 04 artists featured in IMMA’s exhibitions and collection in particular, and about How soon was now? What is Modern and Contemporary Art? Contemporary Art in general, to promote information sharing, and to encourage -Francis Halsall & Declan Long page 08 critical thinking, debate and discussion about art and artists. -

Is Marina Abramović the World's Best-Known Living Artist? She Might

Abrams, Amah-Rose. “Marina Abramovic: A Woman’s World.” Sotheby’s. May 10, 2021 Is Marina Abramović the world’s best-known living artist? She might well be. Starting out in the radical performance art scene in the early 1970s, Abramović went on to take the medium to the masses. Working with her collaborator and partner Ulay through the 1980s and beyond, she developed long durational performance art with a focus on the body, human connection and endurance. In The Lovers, 1998, she and Ulay met in the middle of the Great Wall of China and ended their relationship. For Balkan Baroque, 1997, she scrubbed clean a huge number of cow bones, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for her work. And in The Artist is Present 2010, performed at MoMA in New York, she sat for eight hours a day engaging in prolonged eye contact over three months – it was one of the most popular exhibits in the museum’s history. Since then, she has continued to raise the profile of artists around the world by founding the Marina Abramović Institute, her organisation aimed at expanding the accessibility of time- based work and creating new possibilities for collaboration among thinkers of all fields. MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ / ULAY, THE LOVERS, MARCH–JUNE 1988, A PERFORMANCE THAT TOOK PLACE ACROSS 90 DAYS ON THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA. © MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ AND ULAY, COURTESY: THE MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES / DACS 2021. Fittingly for someone whose work has long engaged with issues around time, Marina Abramović has got her lockdown routine down. She works out, has a leisurely breakfast, works during the day and in the evening, she watches films. -

Mind Over Matter Artforum, Nov, 1996 by Hans-Ulrich Obrist

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_n3_v35/ai_18963443/ Mind over matter ArtForum, Nov, 1996 by Hans-Ulrich Obrist At the Kunsthalle Bern, where Szeemann made his reputation during his eight-year tenure, he organized twelve to fifteen exhibitions a year, turning this venerable institution into a meeting ground for emerging European and American artists. His coup de grace, "When Attitudes Become Form: Live in Your Head," was the first exhibition to bring together post-Minimalist and Conceptual artists in a European institution, and marked a turning point in Szeemann's career - with this show his aesthetic position became increasingly controversial, and due to interference and pressure to adjust his programming from the Kunsthalle's board of directors and Bern's municipal government, he resigned, and set himself up as an Independent curator. If Szeemann succeeded in transforming Bern's Kunsthalle into one of the most dynamic institutions of its time, his 1972 version of Documenta did no less for this art-world staple, held every five years in Kassel, Germany. Conceived as a "100-Day Event," it brought together artists such as Richard Serra, Paul Thek, Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas, and Rebecca Horn, and included not only painting and sculpture but installations, performances, Happenings, and, of course, events that lasted the full 100 days, such as Joseph Beuys' Office for Direct Democracy. Artists have always responded to Szeemann and his approach to curating, which he himself describes as a "structured chaos." Of "Monte Verita," a show mapping the visionary utopias of the early twentieth century, Mario Merz said Szeemann "visualized the chaos we, as artists, have in our heads. -

Stillness in Time (1994)

Stillness in Time (1994) Transcription Notes: If you read through many of the old interviews done with Stuart you will know that he was highly inspired by Latin rhythm and time concepts. Although Jay liked this aspect of his playing, none of it really showed up on the !rst album. By the time the ‘The Return of the Space Cowboy’ was released, Stu’s Latin vibe was clearly showing through – possibly due to the arrival of new drummer Derrick McKenzie too. ‘Stillness in Time’ is by far one of the most technical Jamiroquai bass lines in terms of timing. The bass line is predominately based on a root-!fth movement which sometimes includes the 9th also. He then embellishes on top of this to "esh-out the bass part more - but this basic and common outline is always there. This is another of those tracks using the Warwick 4 string. The sound is not so de!ned and since it is an airy Latin/Samba groove, a lot of the notes are tied over to ring. The sound you are aiming to replicate (or get similar to) the record would be to boost the bass a little and add extra middle to your sound. Make sure it is smooth and punchy – muddy isn’t a bad sound for this track, particularly almost Dub like. You will be required to use the full extent of your technique on this track to nail it well. Try to consistently be a bar or two ahead of your playing (sight reading wise) so you are aware of what is approaching. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

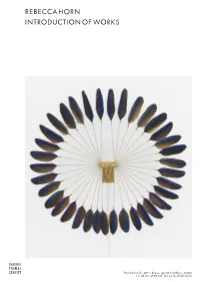

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

Michael Bolton His Brandnewsinglecan 1Touch You...There? "Taken from the Forthcoming Columbia Release: Michael Bolton Greatest Hits 1985-1995

MAKING WAVES: Ad Sales For Specialist Formats... see page 8 LUME 12, ISSUE 35 SEPTEMBER 2, 1995 Blur Is Highest New Entry In Eurochart £2.95 DM8 FFR25 US$5 DFL8.50 At No.7 Page 19 Armatrading Meets Mandela PopKomm Bigger Than Ever, Say Industry Insiders by Jeff Clark -Meads In his keynote speech at assuredness on the German PopKomm, ThomasStein, music scene." COLOGNE -The German music chairmanoftheGerman Stein, who is also president industry and the annual trade label's group BPW, stated, "We of BMG Ariola in the German- fair it hosts are growing in in the recorded music industry speaking territories, went on size and confi- are proud ofto say that Germany has now dence together, PopKomm. joined the ranks of the world's according to the That is most importantrepertoire leadersof the becausePop- sources (for detailed story, see country's record POP Komm has page 5). companies. now estab- PopKomm,heldinthe PopKomm, KOMM. lished itself as gigantic Cologne Congress held in Cologne the world's Centre, this year attracted 600 The high point of BMG artist Joan Armatrading's current world tour was from August 17- Die Hesse fiir biggest music exhibiting companies and her meeting with Nelson Mandela. One of her "dreams came true" when 20, is being trade fair and occupied 180.000 square feet she met him while in Pretoria to promote her latest album What's Inside. toutedasthe Popmusik andit takes place of exhibition space-twice as During a one-to-one meeting at his residence, Mandela signed a copy of world'sbiggest Entertainment in Germany. -

Pop / Rock / Commercial Music Wed, 25 Aug 2021 21:09:33 +0000 Page 1

Pop / Rock / Commercial music www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note 10000 MANIACS The wishing chair 19160 1xLP Elektra Warner GER 960428-1 EX/EX 10,00 € RE 10CC Look hear? 1413 1xLP Warner USA BSK3442 EX+/VG 7,75 € PRO 10CC Live and let live 6546 2xLP Mercury USA SRM28600 EX/EX 18,00 € GF-CC Phonogram 10CC Good morning judge 8602 1x7" Mercury IT 6008025 VG/VG 2,60 € \Don't squeeze me like… Phonogram 10CC Bloody tourists 8975 1xLP Polydor USA PD-1-6161 EX/EX 7,75 € GF 10CC The original soundtrack 30074 1xLP Mercury Back to EU 0600753129586 M-/M- 15,00 € RE GF 180g black 13 ENGINES A blur to me now 1291 1xCD SBK rec. Capitol USA 7777962072 USED 8,00 € Original sticker attached on the cover 13 ENGINES Perpetual motion 6079 1xCD Atlantic EMI CAN 075678256929 USED 8,00 € machine 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says 2486 1xLP Buddah Helidon YU 6.23167AF EX-/VG+ 10,00 € Verty little woc COMPANY 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says-The best of 3541 1xCD Buddha BMG USA 886972424422 12,90 € COMPANY 1910 Fruitgum co. 2 CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb 23685 1xDVD Masterworks Sony EU 0888837454193 10,90 € 2 UNLIMITED Edge of heaven (5 vers.) 7995 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558049 USED 3,00 € 2 UNLIMITED Wanna get up (4 vers.) 12897 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558001 USED 3,00 € 2K ***K the millennium (3 7873 1xCDs Blast first Mute EU 5016027601460 USED 3,10 € Sample copy tracks) 2PLAY So confused (5 tracks) 15229 1xCDs Sony EU NMI 674801 2 4,00 € Incl."Turn me on" 360 GRADI Ba ba bye (4 tracks) 6151 1xCDs Universal IT 156 762-2 -

A Nonverbal Language for Imagining and Learning: Dance Education in K–12 Curriculum Judith Lynne Hanna

A Nonverbal Language for Imagining and Learning: Dance Education in K–12 Curriculum Judith Lynne Hanna Curriculum theorists have provided a knowledge base concerning the common, narrow, in-depth focus for articles and instead aesthetics, agency, creativity, lived experience, transcendence, learn- address a panorama of issues that educators, dancers, and ing through the body, and the power of the arts to engender visions researchers have been raising, at least since my teacher training at of alternative possibilities in culture, politics, and the environment. the University of California–Los Angeles in the late 1950s. Underlying the discussion is the theoretical work of John However, these theoretical threads do not reveal the potential of Dewey (1934) and Eliot Eisner (2002), who have looked at the K–12 dance education. Research on nonverbal communication and arts broadly. They have established the significance of the expres- cognition, coupled with illustrative programs, provides key insights sion of agency, creativity, lived experience, transcendence, learn- into dance as a distinct performing art discipline and as a liberal ing through the body, and the power of the arts to engender applied art that fosters creative problem solving and the acquisition, visions of alternative possibilities in culture, politics, and the envi- reinforcement, and assessment of nondance knowledge. Synthesizing ronment. Dewey’s prolific writing and teaching at Teachers College of Columbia University prepared schools to offer dance and interpreting theory and research from different disciplines that for all children. He believed that children learn by doing—action is relevant to dance education, this article addresses cognition, emo- being the test of comprehension, and imagination the result of the tion, language, learning styles, assessment, and new research direc- mind blending the old and familiar to make it new in experience. -

Catalogue 234 Jonathan A

Catalogue 234 Jonathan A. Hill Bookseller Art Books, Artists’ Books, Book Arts and Bookworks New York City 2021 JONATHAN A. HILL BOOKSELLER 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10 b New York, New York 10023-8143 home page: www.jonathanahill.com JONATHAN A. HILL mobile: 917-294-2678 e-mail: [email protected] MEGUMI K. HILL mobile: 917-860-4862 e-mail: [email protected] YOSHI HILL mobile: 646-420-4652 e-mail: [email protected] Further illustrations can be seen on our webpage. Member: International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America We accept Master Card, Visa, and American Express. Terms are as usual: Any book returnable within five days of receipt, payment due within thirty days of receipt. Persons ordering for the first time are requested to remit with order, or supply suitable trade references. Residents of New York State should include appropriate sales tax. COVER ILLUSTRATION: © 2020 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York PRINTED IN CHINA 1. ART METROPOLE, bookseller. [From upper cover]: Catalogue No. 5 – Fall 1977: Featuring european Books by Artists. Black & white illus. (some full-page). 47 pp. Large 4to (277 x 205 mm.), pictorial wrap- pers, staple-bound. [Toronto: 1977]. $350.00 A rare and early catalogue issued by Art Metropole, the first large-scale distributors of artists’ books and publications in North America. This catalogue offers dozens of works by European artists such as Abramovic, Beuys, Boltanski, Broodthaers, Buren, Darboven, Dibbets, Ehrenberg, Fil- liou, Fulton, Graham, Rebecca Horn, Hansjörg Mayer, Merz, Nannucci, Polke, Maria Reiche, Rot, Schwitters, Spoerri, Lea Vergine, Vostell, etc.