A Nonverbal Language for Imagining and Learning: Dance Education in K–12 Curriculum Judith Lynne Hanna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Stillness in Time (1994)

Stillness in Time (1994) Transcription Notes: If you read through many of the old interviews done with Stuart you will know that he was highly inspired by Latin rhythm and time concepts. Although Jay liked this aspect of his playing, none of it really showed up on the !rst album. By the time the ‘The Return of the Space Cowboy’ was released, Stu’s Latin vibe was clearly showing through – possibly due to the arrival of new drummer Derrick McKenzie too. ‘Stillness in Time’ is by far one of the most technical Jamiroquai bass lines in terms of timing. The bass line is predominately based on a root-!fth movement which sometimes includes the 9th also. He then embellishes on top of this to "esh-out the bass part more - but this basic and common outline is always there. This is another of those tracks using the Warwick 4 string. The sound is not so de!ned and since it is an airy Latin/Samba groove, a lot of the notes are tied over to ring. The sound you are aiming to replicate (or get similar to) the record would be to boost the bass a little and add extra middle to your sound. Make sure it is smooth and punchy – muddy isn’t a bad sound for this track, particularly almost Dub like. You will be required to use the full extent of your technique on this track to nail it well. Try to consistently be a bar or two ahead of your playing (sight reading wise) so you are aware of what is approaching. -

Hip Hop Dance: Performance, Style, and Competition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank HIP HOP DANCE: PERFORMANCE, STYLE, AND COMPETITION by CHRISTOPHER COLE GORNEY A THESIS Presented to the Department ofDance and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofFine Arts June 2009 -------------_._.. _--------_...._- 11 "Hip Hop Dance: Performance, Style, and Competition," a thesis prepared by Christopher Cole Gorney in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofFine Arts degree in the Department ofDance. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Jenife .ning Committee Date Committee in Charge: Jenifer Craig Ph.D., Chair Steven Chatfield Ph.D. Christian Cherry MM Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School 111 An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Christopher Cole Gorney for the degree of Master ofFine Arts in the Department ofDance to be taken June 2009 Title: HIP HOP DANCE: PERFORMANCE, STYLE, AND COMPETITION Approved: ----- r_---- The purpose ofthis study was to identify and define the essential characteristics ofhip hop dance. Hip hop dance has taken many forms throughout its four decades ofexistence. This research shows that regardless ofthe form there are three prominent characteristics: performance, personal style, and competition. Although it is possible to isolate the study ofeach ofthese characteristics, they are inseparable when defining hip hop dance. There are several genre-specific performance formats in which hip hop dance is experienced. Personal style includes the individuality and creativity that is celebrated in the hip hop dancer. Competition is the inherent driving force that pushes hip hop dancers to extend the form's physical limitations. -

Michael Bolton His Brandnewsinglecan 1Touch You...There? "Taken from the Forthcoming Columbia Release: Michael Bolton Greatest Hits 1985-1995

MAKING WAVES: Ad Sales For Specialist Formats... see page 8 LUME 12, ISSUE 35 SEPTEMBER 2, 1995 Blur Is Highest New Entry In Eurochart £2.95 DM8 FFR25 US$5 DFL8.50 At No.7 Page 19 Armatrading Meets Mandela PopKomm Bigger Than Ever, Say Industry Insiders by Jeff Clark -Meads In his keynote speech at assuredness on the German PopKomm, ThomasStein, music scene." COLOGNE -The German music chairmanoftheGerman Stein, who is also president industry and the annual trade label's group BPW, stated, "We of BMG Ariola in the German- fair it hosts are growing in in the recorded music industry speaking territories, went on size and confi- are proud ofto say that Germany has now dence together, PopKomm. joined the ranks of the world's according to the That is most importantrepertoire leadersof the becausePop- sources (for detailed story, see country's record POP Komm has page 5). companies. now estab- PopKomm,heldinthe PopKomm, KOMM. lished itself as gigantic Cologne Congress held in Cologne the world's Centre, this year attracted 600 The high point of BMG artist Joan Armatrading's current world tour was from August 17- Die Hesse fiir biggest music exhibiting companies and her meeting with Nelson Mandela. One of her "dreams came true" when 20, is being trade fair and occupied 180.000 square feet she met him while in Pretoria to promote her latest album What's Inside. toutedasthe Popmusik andit takes place of exhibition space-twice as During a one-to-one meeting at his residence, Mandela signed a copy of world'sbiggest Entertainment in Germany. -

Pop / Rock / Commercial Music Wed, 25 Aug 2021 21:09:33 +0000 Page 1

Pop / Rock / Commercial music www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note 10000 MANIACS The wishing chair 19160 1xLP Elektra Warner GER 960428-1 EX/EX 10,00 € RE 10CC Look hear? 1413 1xLP Warner USA BSK3442 EX+/VG 7,75 € PRO 10CC Live and let live 6546 2xLP Mercury USA SRM28600 EX/EX 18,00 € GF-CC Phonogram 10CC Good morning judge 8602 1x7" Mercury IT 6008025 VG/VG 2,60 € \Don't squeeze me like… Phonogram 10CC Bloody tourists 8975 1xLP Polydor USA PD-1-6161 EX/EX 7,75 € GF 10CC The original soundtrack 30074 1xLP Mercury Back to EU 0600753129586 M-/M- 15,00 € RE GF 180g black 13 ENGINES A blur to me now 1291 1xCD SBK rec. Capitol USA 7777962072 USED 8,00 € Original sticker attached on the cover 13 ENGINES Perpetual motion 6079 1xCD Atlantic EMI CAN 075678256929 USED 8,00 € machine 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says 2486 1xLP Buddah Helidon YU 6.23167AF EX-/VG+ 10,00 € Verty little woc COMPANY 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says-The best of 3541 1xCD Buddha BMG USA 886972424422 12,90 € COMPANY 1910 Fruitgum co. 2 CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb 23685 1xDVD Masterworks Sony EU 0888837454193 10,90 € 2 UNLIMITED Edge of heaven (5 vers.) 7995 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558049 USED 3,00 € 2 UNLIMITED Wanna get up (4 vers.) 12897 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558001 USED 3,00 € 2K ***K the millennium (3 7873 1xCDs Blast first Mute EU 5016027601460 USED 3,10 € Sample copy tracks) 2PLAY So confused (5 tracks) 15229 1xCDs Sony EU NMI 674801 2 4,00 € Incl."Turn me on" 360 GRADI Ba ba bye (4 tracks) 6151 1xCDs Universal IT 156 762-2 -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants. -

Dance, Space and Subjectivity

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CHICHESTER an accredited college of the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON DANCE, SPACE AND SUBJECTIVITY Valerie A. Briginshaw This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by publication. DANCE DEPARTMENT, SCHOOL OF THE ARTS October 2001 This thesis has been completed as a requirement for a higher degree of the University of Southampton. WS 2205643 2 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 ..::r'.). NE '2...10 0 2. UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CmCHESTER an accredited college of the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DANCE Doctor of Philosophy DANCE, SPACE AND SUBJECTIVITY by Valerie A. Briginshaw This thesis has been completed as a requirement for a higher degree of the University of Southampton Thisthesis, by examining relationships between dancing bodies and space, argues that postmodern dance can challenge traditional representations of subjectivity and suggest alternatives. Through close readings of postmodern dances, informed by current critical theory, constructions of subjectivity are explored. The limits and extent of subjectivity are exposed when and where bodies meet space. Through a precise focus on this body/space interface, I reveal various ways in which dance can challenge, trouble and question fixed perceptions of subjectivity. The representation in dance of the constituents of difference that partly make up subjectivity, (such as gender, 'race', sexuality and ability), is a main focus in the exploration of body/space relationships presented in the thesis. Based on the premise that dance, space and subjectivity are constructions that can mutually inform and construct each other, this thesis offers frameworks for exploring space and subjectivity in dance. These explorations draw on a selective reading of pertinent poststructuralist theories which are all concerned with critiquing the premises of Western philosophy, which revolve around the concept of an ideal, rational, unified subject, which, in turn, relies on dualistic thinking that enforces a way of seeing things in terms of binary oppositions. -

Exploring the Relationship Between Movement and Dance

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 2016 Movement and Music: Exploring the Relationship Between Movement and Dance Savannah Dunn Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Dance Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dunn, Savannah, "Movement and Music: Exploring the Relationship Between Movement and Dance" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 357. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Movement and Music: Exploring the Relationship Between Music and Dance A Thesis Presented to the Department of Dance Jordan College of the Arts and The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Savannah Dunn 26 March 2016 2 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….pg. 4 Historical & Contemporary Context……………….………………………………………..pg. 14 Elements of Choreography………………………………………………………………….pg. 18 Analysis of Personal Process………………………………………………………………..pg. 27 Balance/ Choreographing in Silence………………………………………....……...pg. 30 Ash/ Choreographing -

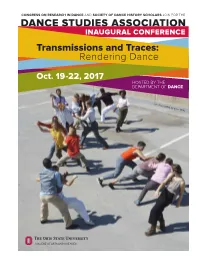

Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance

INAUGURAL CONFERENCE Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance Oct. 19-22, 2017 HOSTED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF DANCE Sel Fou! (2016) by Bebe Miller i MAKE YOUR MOVE GET YOUR MFA IN DANCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN We encourage deep engagement through the transformative experiences of dancing and dance making. Hone your creative voice and benefit from an extraordinary breadth of resources at a leading research university. Two-year MFA includes full tuition coverage, health insurance, and stipend. smtd.umich.edu/dance CORD program 2017.indd 1 ii 7/27/17 1:33 PM DEPARTMENT OF DANCE dance.osu.edu | (614) 292-7977 | NASD Accredited Congratulations CORD+SDHS on the merger into DSA PhD in Dance Studies MFA in Dance Emerging scholars motivated to Dance artists eager to commit to a study critical theory, history, and rigorous three-year program literature in dance THINKING BODIES / AGILE MINDS PhD, MFA, BFA, Minor Faculty Movement Practice, Performance, Improvisation Susan Hadley, Chair • Harmony Bench • Ann Sofie Choreography, Dance Film, Creative Technologies Clemmensen • Dave Covey • Melanye White Dixon Pedagogy, Movement Analysis Karen Eliot • Hannah Kosstrin • Crystal Michelle History, Theory, Literature Perkins • Susan Van Pelt Petry • Daniel Roberts Music, Production, Lighting Mitchell Rose • Eddie Taketa • Valarie Williams Norah Zuniga Shaw Application Deadline: November 15, 2017 iii DANCE STUDIES ASSOCIATION Thank You Dance Studies Association (DSA) We thank Hughes, Hubbard & Reed LLP would like to thank Volunteer for the professional and generous legal Lawyers for the Arts (NY) for the support they contributed to the merger of important services they provide to the Congress on Research in Dance and the artists and arts organizations. -

THE CAMP of the SAINTS by Jean Raspail

THE CAMP OF THE SAINTS By Jean Raspail And when the thousand years are ended, Satan will be released from his prison, and will go forth and deceive the nations which are in the four corners of the earth, Gog and Magog, and will gather them together for the battle; the number of whom is as the sand of the sea. And they went up over the breadth of the earth and encompassed the camp of the saints, and the beloved city. —APOCALYPSE 20 My spirit turns more and more toward the West, toward the old heritage. There are, perhaps, some treasures to retrieve among its ruins … I don’t know. —LAWRENCE DURRELL As seen from the outside, the massive upheaval in Western society is approaching the limit beyond which it will become “meta-stable” and must collapse. —SOLZHENITSYN Translated by Norman Shapiro I HAD WANTED TO WRITE a lengthy preface to explain my position and show that this is no wild-eyed dream; that even if the specific action, symbolic as it is, may seem farfetched, the fact remains that we are inevitably heading for something of the sort. We need only glance at the awesome population figures predicted for the year 2000, i.e., twenty-eight years from now: seven billion people, only nine hundred million of whom will be white. But what good would it do? I should at least point out, though, that many of the texts I have put into my characters’ mouths or pens—editorials, speeches, pastoral letters, laws, news Originally published in French as Le Camp Des Saints, 1973 stories, statements of every description—are, in fact, authentic. -

Western Michigan University, Department of Dance Course Descriptions

Western Michigan University, Department of Dance Course Descriptions DANC 1000 First Year Performance Workshops and experiences related to expanding the student’s understanding of dance as an art form and introduction of general skills necessary for a career in dance. Course culminates in performances in the final dances choreographed by DANC 3800 students. Restricted dance majors. 2 hours DANC 1010 Beginning Ballet Elementary ballet technique for the general student. The emphasis is placed on line, control, alignment and musicality. Students will learn elementary combinations utilizing fundamental classical ballet vocabulary. 2 hours DANC 1020 Beginning Jazz Elementary jazz technique for the general student. Rhythmical integration of isolated movements with emphasis on dynamics, style and performance is stressed. 2 hours DANC 1030 Beginning Modern Elementary modern technique for the general student. The emphasis is placed on body integration, locomotor skills, dynamic variety, and musicality. 2 hours DANC 1040 Beginning Tap Elementary tap technique for the general student, emphasizing the basic terminology as well as an investigation of rhythm and improvisation as audibly produced by the feet. Some turns and stylized arm movements may be included. 2 hours DANC 1100 Ballet Technique I An introduction to the art of ballet, designed for dance majors and minors, primarily concerned with development of ballet technique. Emphasis is placed on basic ballet movement sequences and patterns used to develop control, balance, alignment, musicality, strength and vocabulary at the elementary level. Students will continue in DANC 1100 until advanced to DANC 2100 by the instructor. The content of this course varies each semester. Repeatable for credit. Prerequisite: Advisor approval. -

Dance and Politics: Moving Beyond Boundaries

i Dance and politics ii iii Dance and politics Moving beyond boundaries Dana Mills Manchester University Press iv Copyright © Dana Mills 2017 The right of Dana Mills to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing- in- Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data applied for ISBN 978 1 5261 0514 1 hardback ISBN 978 1 5261 0515 8 paperback First published 2017 The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third- party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Typeset in Minion by Out of House Publishing v In song and dance man expresses himself as a member of a higher commu- nity: he has forgotten how to walk and speak and is on the way forward flying into the air, dancing. Friedrich Nietzsche You have to love dancing to stick to it. It gives you nothing back, no manuscripts to store away, no paintings to show on walls and maybe hang in museums, no poems to be printed and sold, nothing but that single fleeting moment when you feel alive. Merce Cunningham vi For my father, Harold Mills, who taught me how to love dance, books and the world.