Kathak's Marginalized Courtesan Tradition the I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proclamation to the People of Oude on Its Annexation. February 1856

404 Indian Uprising/Sepoy Mutiny source: These illustrated biographies of the Indian rebels are from P. N. Chopra, ed., The Who’s Who of Indian Martyrs, 3 vols. (New Delhi: Ministry of Education and Youth Services, Govern- ment of India, 1969–1973). Proclamation to the People of Oude on its Annexation. February 1856 [This document contains the East India Company’s rationalization for its annexation of the Bengal region. The Company is depicted as a rescuing party whose gentle and superior government will ensure happiness and pro- tect the Indian people from unjust and exorbitant indigenous practices. The document presents the Company as a humanizing enterprise whose primary concern is civilizing India; the East India Company’s trading interests and mercantile mission are not referred to in the announcement.] By a treaty concluded in the year 1801, the Honourable East India Company engaged to protect the Sovereign of Oude against every foreign and domestic enemy, while the Sovereign of Oude, upon his part, bound himself to estab- lish ‘‘such a system of administration, to be carried into e√ect by his own o≈cers, as should be conducive to the prosperity of his subjects, and calcu- lated to secure the lives and property of the inhabitants.’’ The obligations which the treaty imposed upon the Honourable East India Company have been observed by it for more than half a century, faithfully, constantly, and completely. In all that time, though the British Government has itself been engaged in frequent wars, no foreign foe has ever set his foot on the soil of Oude; no rebellion has ever threatened the stability of its throne; British troops have been stationed in close promixity to the king’s person, and their aid has never been withheld whenever his power was wrongfully defied. -

Contemporary Art in Indian Context

Artistic Narration, Vol. IX, 2018, No. 2: ISSN (P) : 0976-7444 (e) : 2395-7247Impact Factor 6.133 (SJIF) Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Richa Singh Asso. Prof., Research Scholar Deptt. of Drawing & Painting M.F.A. M.M.H. College B.Ed. Ghaziabad, U.P. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Abstract: This article has a focus on Contemporary Art in Indian context. Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Through this article emphasizesupon understanding the changes in Richa Singh, Contemporary Art over a period of time in India right from its evolution to the economic liberalization period than in 1990’s and finally in the Contemporary Art in current 21st century. The article also gives an insight into the various Indian Context, techniques and methods adopted by Indian Contemporary Artists over a period of time and how the different generations of artists adopted different techniques in different genres. Finally the article also gives an insight Artistic Narration 2018, into the current scenario of Indian Contemporary Art and the Vol. IX, No.2, pp.35-39 Contemporary Artists reach to the world economy over a period of time. key words: Contemporary Art, Contemporary Artists, Indian Art, 21st http://anubooks.com/ Century Art, Modern Day Art ?page_id=485 35 Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai, Richa Singh Contemporary Art Contemporary Art refers to art – namely, painting, sculpture, photography, installation, performance and video art- produced today. Though seemingly simple, the details surrounding this definition are often a bit fuzzy, as different individuals’ interpretations of “today” may widely vary. -

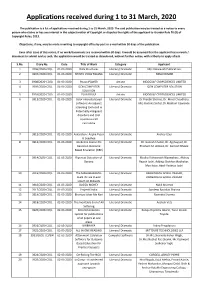

Applications Received During 1 to 31 March, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 3906/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Data Structures Literary/ Dramatic M/s Amaravati Publications 2 3907/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 SHISHU VIKAS YOJANA Literary/ Dramatic NIRAJ KUMAR 3 3908/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 Picaso POWER Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 4 3909/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 ICON COMPUTER Literary/ Dramatic ICON COMPUTER SOLUTION SOLUTION 5 3910/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 PLANOGULF Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 6 3911/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Color intensity based Literary/ Dramatic Dr.Preethi Sharma, Dr. Minal Chaudhary, software: An adjunct Mrs.Ruchika Sinhal, Dr.Madhuri Gawande screening tool used in Potentially malignant disorders and Oral squamous cell carcinoma 7 3912/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Aakarshan : Aapke Pyaar Literary/ Dramatic Akshay Gaur ki Seedhee 8 3913/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Academic course file Literary/ Dramatic Dr. -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Tejaswini Ganti Recitations

1 Cultures and Contexts: India – CORE UA-516 Spring 2020/TTH 9:30-10:45 AM/Silver 414 Professor: Tejaswini Ganti Recitations Teaching Assistant: Leela Khanna 003: Friday 9:30-10:45AM – GCASL 384 004: Friday 11:00-12:15AM – Bobst LL142 Office: 25 Waverly Place, # 503 Hours: Mon. 3:00-4:30pm or by appointment Phone: 998-2108 Email: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION This course introduces the history, culture, society, and politics of modern India. Home to over one billion people, eight major religions, twenty official languages (with hundreds of dialects), histories spanning several millennia, and a tremendous variety of customs, traditions, and ways of life, India is almost iconic for its diversity. We examine the challenges posed by such diversity as well as how this diversity has been understood, represented, and managed, both historically and contemporarily. Topics to be covered include the politics of representation and knowledge production; the long histories of global connections; colonialism; social categories such as caste, class, ethnicity, gender, and religion; projects of nation-building; and popular culture. LEARNING OBJECTIVES § To recognize that knowledge about a country/region/community whether it is historical or cultural is never produced in a vacuum but is always inflected by issues of power. § To develop the ability to question our assumptions and interrogate our commonsensical understandings about India that are circulated through the media, political commentary, and self- appointed cultural gatekeepers. § To recognize that what we take as given or as essential social and cultural realities are, in fact, constructed norms and practices that have specific histories. -

The Modes of Representation of Faces in South Asian Painting

<Research Notes>Profiled Figures: The Modes of Title Representation of Faces in South Asian Painting Author(s) IKEDA, Atsushi イスラーム世界研究 : Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies Citation (2017), 10: 67-82 Issue Date 2017-03-20 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/225230 ©京都大学大学院アジア・アフリカ地域研究研究科附属 Right イスラーム地域研究センター 2017 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University イスラーム世界研究 第 10 巻(2017 年 3 月)67‒82 頁 Profiled Figures Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies, 10 (March 2017), pp. 67–82 Profiled Figures: The Modes of Representation of Faces in South Asian Painting IKEDA Atsushi* Introduction This paper argues that South Asian people’s physical features such as eye and nose prompted Hindu painters to render figures in profile in the late medieval and early modern periods. In addition, I would like to explore the conceptual and theological meanings of each mode i.e. the three quarter face, the profile view, and the frontal view from both Islamic and Hindu perspectives in order to find out the reasons why Mughal painters adopted the profile as their artistic standard during the reign of Jahangīr (1605–27). Various facial modes characterized South Asian paintings at each period. Perhaps the most important example of paintings in South Asia dates from B.C. 1 to A.C. 5 century and is located in the Ajantā cave in India. It depicts Buddhist ascetics in frontal view, while other figures are depicted in three quarter face with their eyes contained within the line that forms the outer edge (Figure 1). Moving to the Ellora cave paintings executed between the 5th and 7th century, some figures show the eye in the far side pushed out of the facial line. -

The Human Rights Argument for Ending Prostitution in India, 28 B.C

Boston College Third World Law Journal Volume 28 | Issue 2 Article 7 4-1-2008 Recognizing Women's Worth: The umH an Rights Argument for Ending Prostitution in India Nicole J. Karlebach Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Women Commons Recommended Citation Nicole J. Karlebach, Recognizing Women's Worth: The Human Rights Argument for Ending Prostitution in India, 28 B.C. Third World L.J. 483 (2008), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj/vol28/iss2/7 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Third World Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECOGNIZING WOMEN’S WORTH: THE HUMAN RIGHTS ARGUMENT FOR ENDING PROSTITUTION IN INDIA Nicole J. Karlebach* INDIAN FEMINISMS: LAW, PATRIARCHIES AND VIOLENCE IN IN- DIA. By Geetanjali Gangoli. Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Company. 2007. Pp. 149. Abstract: In Indian Feminisms: Law, Patriarchies and Violence in India, Geetan- jali Gangoli recounts how the Indian feminist movement, identifiable for its uniquely Indian concepts of womanhood and equal rights, has been effec- tive in promoting equality for women. Gangoli attributes this success to the fact that Indian feminists have influenced legislation and dialogue within the country, while also recognizing the reality of intense divides among castes and religions. This book review examines the vague nature of Indian law in regard to prostitution, a topic that has been the source of extensive feminist debate. -

Indian Art History from Colonial Times to the R.N

The shaping of the disciplinary practice of art Parul Pandya Dhar is Associate Professor in history in the Indian context has been a the Department of History, University of Delhi, fascinating process and brings to the fore a and specializes in the history of ancient and range of viewpoints, issues, debates, and early medieval Indian architecture and methods. Changing perspectives and sculpture. For several years prior to this, she was teaching in the Department of History of approaches in academic writings on the visual Art at the National Museum Institute, New arts of ancient and medieval India form the Delhi. focus of this collection of insightful essays. Contributors A critical introduction to the historiography of Joachim K. Bautze Indian art sets the stage for and contextualizes Seema Bawa the different scholarly contributions on the Parul Pandya Dhar circumstances, individuals, initiatives, and M.K. Dhavalikar methods that have determined the course of Christian Luczanits Indian art history from colonial times to the R.N. Misra present. The spectrum of key art historical Ratan Parimoo concerns addressed in this volume include Himanshu Prabha Ray studies in form, style, textual interpretations, Gautam Sengupta iconography, symbolism, representation, S. Settar connoisseurship, artists, patrons, gendered Mandira Sharma readings, and the inter-relationships of art Upinder Singh history with archaeology, visual archives, and Kapila Vatsyayan history. Ursula Weekes Based on the papers presented at a Seminar, Front Cover: The Ashokan pillar and lion capital “Historiography of Indian Art: Emergent during excavations at Rampurva (Courtesy: Methodological Concerns,” organized by the Archaeological Survey of India). National Museum Institute, New Delhi, this book is enriched by the contributions of some scholars Back Cover: The “stream of paradise” (Nahr-i- who have played a seminal role in establishing Behisht), Fort of Delhi. -

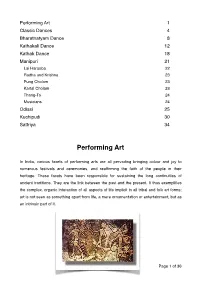

Classical Dances Have Drawn Sustenance

Performing Art 1 Classic Dances 4 Bharatnatyam Dance 8 Kathakali Dance 12 Kathak Dance 18 Manipuri 21 Lai Haraoba 22 Radha and Krishna 23 Pung Cholam 23 Kartal Cholam 23 Thang-Ta 24 Musicians 24 Odissi 25 Kuchipudi 30 Sattriya 34 Performing Art In India, various facets of performing arts are all pervading bringing colour and joy to numerous festivals and ceremonies, and reaffirming the faith of the people in their heritage. These facets have been responsible for sustaining the long continuities of ancient traditions. They are the link between the past and the present. It thus exemplifies the complex, organic interaction of all aspects of life implicit in all tribal and folk art forms; art is not seen as something apart from life, a mere ornamentation or entertainment, but as an intrinsic part of it. Page !1 of !36 Pre-historic Cave painting, Bhimbetka, Madhya Pradesh Under the patronage of Kings and rulers, skilled artisans and entertainers were encouraged to specialize and to refine their skills to greater levels of perfection and sophistication. Gradually, the classical forms of Art evolved for the glory of temple and palace, reaching their zenith around India around 2nd C.E. onwards and under the powerful Gupta empire, when canons of perfection were laid down in detailed treatise - the Natyashastra and the Kamasutra - which are still followed to this day. Through the ages, rival kings and nawabs vied with each other to attract the most renowned artists and performers to their courts. While the classical arts thus became distinct from their folk roots, they were never totally alienated from them, even today there continues a mutually enriching dialogue between tribal and folk forms on the one hand, and classical art on the other; the latter continues to be invigorated by fresh folk forms, while providing them with new thematic content in return. -

View Course Outline

Huron University College English 2363F (Fall 2019) Topics in World Literature in English India’s Peripherals: Literature, Graphic Novels, and Film from the Social Margins Instructor: Dr. Teresa Hubel — e-mail: [email protected]; phone: 438-7224, ext. 219 Office Hours: Mondays, 2:30 – 3:30 pm and by appointment (A306) Classes: Mondays, 12:30 – 2:30 pm and Wednesdays, 1:30 – 2:30 pm in HC W112 Prerequisites: At least 60% in 1.0 of English 1000-1999, or permission of the Department. Antirequisite: English 3884E DESCRIPTION: This course is designed to familiarize students with selected works of literature, graphic novels, and film from India with a specific focus on texts that self- consciously address matters related to gender, caste, class, race, and sexuality. The course begins with the later texts of the British Empire in India and moves through the nationalist period, then settles into explorations of some of the most controversial political and social issues that have challenged the nation since India's independence in 1947. We will consider the emotional and psychological investments behind particular social and political placements within India, such as those associated with Dalits, hijras, lesbians, courtesans, and women. Students will be encouraged to analyze the creative works we will study on the course in relation to the diverse historical, social, and cultural movements to which they have contributed. This is a research-learning course. As such, students will be encouraged to develop original interpretations of creative texts. Selected student essays will be published on the Scholarship @ Huron webpage or submitted to Huron’s undergraduate research journal, Liberated Arts. -

Garden Reach: the Forgotten Kingdom of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah

http://double-dolphin.blogspot.com.es/2017/03/garden-reach-metiabruz-nawab-wajid-ali-shah- calcutta-kolkata.html The Concrete Paparazzi Sunday 19 March 2017 Garden Reach: The Forgotten Kingdom of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah My research into Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab of the Kingdom of Oudh (Awadh) started as a simple question – where was he buried? I knew that he had come to Calcutta once the East India Company had dethroned him. But if he had come to Calcutta, would he have died in Calcutta and if he had died in Calcutta, wouldn’t he have been buried in Calcutta? Google threw up a name – Sibtainabad Imambara. But where was this? Further curiosity would lead me to this post on the Astounding Bengal blog. There were scattered newspaper articles on the Nawab as well, but there seemed to be no one place where I could get the complete information. That is when I knew that I would have to do this myself, and as a friend and collaborator, I found Shaikh Sohail, who has the twin advantages of being a resident of the area where the Nawab once stayed and being on good terms with his descendants. More than 100 years after he died, are there any vestiges of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah that still remain? JAB CHHOR CHALEY LUCKNOW NAGRI It is important to begin by addressing a common misconception. In 1799, when Tipu Sultan was killed when the British stormed Srirangapatnam, the East India Company exiled his family to Calcutta to prevent them from stirring up any more trouble in the South. -

![The Ethnographic [Feministic-Legal] Comparative Study on Life Style of Female Prostitutes in the Historic and Contemporary India Having Reference to Their Status](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1687/the-ethnographic-feministic-legal-comparative-study-on-life-style-of-female-prostitutes-in-the-historic-and-contemporary-india-having-reference-to-their-status-631687.webp)

The Ethnographic [Feministic-Legal] Comparative Study on Life Style of Female Prostitutes in the Historic and Contemporary India Having Reference to Their Status

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 2, Issue - 2, Feb – 2018 UGC Approved Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 3.449 Publication Date: 28/02/2018 The Ethnographic [Feministic-Legal] Comparative Study on Life Style of Female Prostitutes In The Historic And Contemporary India Having Reference To Their Status B.Leelesh Sundaram 2nd year B.B.A, LL.B (hons), Saveetha School of Law, Saveetha University. Email - [email protected] Abstract: The nature has bestowed the beautiful capacity of bringing life into the world within women. Women are globally perceived as the purest form of beings in the world. India being a part of south Asian continent has given spiritual and ethnical importance to women at high extent, but this concept is hindered by the practice of prostitution. India is identified as one of the greatest centres of illegal prostitution practice in the contemporary society. The practice of prostitution in India is a part of the society from time in memorial and literature helps us understand the situation of prostitutes in Indian history. Though there has been a number of research and discussion done on prostitution in India, an ambiguity still prevail with respect to life style of female prostitutes in India by ethnographically comparing it with their lifestyle in historic owing special attention to their status. This research aims to study the extent of prostitution in India and compare the life style of prostitute in historic and contemporary India. The paper tries to analyze the status of prostitutes in historic and contemporary India and also find out the reaction towards prostitution in Contemporary and Historic India.