"Lambeth 1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Episcopal Journal December 2018 News

Episcopal JOURNALMONTHLY EDITION | $3.75 PER COPY VOL. 8 NO. 12 | DECEMBER 2018 Bishops offer litany The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness after gun killings did not overcome it. [The advocacy group Bishops Against Gun Violence released this letter and john 1:5 3 litany on Nov. 8, shortly after a massacre in Thousand Oaks, Calif.] Diocese pursues recovery after e mourn the murder of 12 precious children of God in fatal accident Thousand Oaks, Calif., and we NEWS weep for those who have lost peo- Wple who were dear to them. We of- fer our prayers for solace, for healing and for a change of heart among the elected leaders whose unwillingness to enact safe gun legisla- tion puts us all at risk. Much of what can be said in the wake of such appalling carnage has been said. It was said after the mass shooting at the Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisc., and it was said after the Sandy Hook Elementary School tragedy in Newtown, Conn., the two devastating events that brought Bishops United Against Gun Violence into being. And it was said most Photo/Wikimedia Commons/Pomeranian State Museum, Germany 6 “Adoration of the Shepherds,” by Gerard van Honthorst (1622) Leaders vow recently after the anti-Semitic massacre at the Tree of Life Synagogue support after in Pittsburgh. Mass shootings occur so frequently in our country that synagogue attack there are people who have survived more than one. “Litany in the wake of a mass shooting,” to commemorate the dead, to NEWS While the phrase “thoughts and prayers” might have become de- comfort their loved ones and to honor survivors and first responders. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

May 16, 2021 May 10 in the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, Today We Pray for the Diocese of Cascadi

Anglican Prayer Cycle May 10, 2020 – May 16, 2021 May 10 In the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, today we pray for the Diocese of Cascadia and Bishop Kevin Bond Allen and his wife, Stefanie. Almighty Father, we pray that they may be faithful witnesses for Jesus Christ and empowered by your Holy Spirit to serve you in the world. May 17 In the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, today we pray for the Diocese of Western Anglicans and Bishop Keith Andrews and his wife, Gail. May 24 In the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, today we pray for the International Diocese and Bishop Bill Atwood and his wife, Susan. May 31 In the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, today we pray for the Anglican Province of the Indian Ocean and The Rt. Rev. James Wong, Archbishop June 7 In the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, today we pray for the Anglican Diocese of the Living Word, for Bishop Julian Dobbs, and his wife, Brenda and Bishop David Bena and his wife Mary Ellen. June 14 In the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, today we pray for the College of Bishops Meeting, Provincial Council and Assembly, June 22-24. June21 In the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, today we pray for The Rt. Rev. Michael Lewis, Bishop of Jerusalem and the Middle East. June 28 In the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, today we pray for the Fellowship of Confessing Anglicans, the Confessing Anglican Diocese in New Zealand and The Rt. Rev. Jay Behan, Bishop. July 5 In the ACNA Cycle of Prayer, today we pray for the Diocese of Pittsburgh, Bishop Jim Hobby and his wife, Shari. -

Download Seed & Harvest | Fall/Winter 2020

Seed & Harvest TRINITY SCHOOL FOR MINISTRY FALL/WINTER 2020 Celebrating the consecration of Church of Christ our Peace (CCOP) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in conjunction with the 25th Anniversary Celebration of the Deanery of Cambodia. This building also houses the National Office of the Deanery. In this issue, we share good news about the growth of the six deaneries in Southeast Asia. See the full article on page 9, written by the Rev. Canon Yee Ching Wah, who is a good friend of Trinity School for Ministry, and supporter of our mission. Registration for 2021 January InterTerm ends soon! See pages 16-18 for details. IN THIS ISSUE Seed & Harvest VOLUME 43 | NUMBER 1 3 From the Dean and President 4 Hope: An Abiding Grace PRODUCTION STAFF 5 Planting Churches: Being Doers of the Word [email protected] Executive Editor 6 Planting Hope Through Prayer The Very Rev. Dr. Henry L. Thompson III 9 Anglican Mission in Southeast Asia [email protected] 12 Church Planting in Anathoth General Editor 14 Serving God May Require Some Pruning, Uprooting, Mary Lou Harju and Planting [email protected] 16 January InterTerm 2021 Layout and Design Alexandra Morra 19 Meeting the Need for Theological Education in Latin America SOLI DEO GLORIA 20 Alumni News 22 Formation...at a Distance 23 For the Proclamation of the Gospel 24 Giving Generously During the Pandemic 25 Stewardship and Generosity in an Age of Coronavirus Dean and President 26 In Memoriam The Very Rev. Dr. Henry L. Thompson III 29 New Opportunities to Serve [email protected] 29 From Our Bookshelf Academic Dean Dr. -

Jo Urna L O F the 22 8 an N U a L Co N V E N Tio N

The Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut 2012 Annual Convention th Journal of the 228 the of Journal Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut 1335 Asylum Avenue Hartford, CT 06105 860-233-4481 (main) 860-523-1410 (fax) Table of Contents People, Committees, & Communities Officers of our Diocese, Committees, Commissions 2 Deaneries 4 Diocesan Staff 6 Parishes & Mission Stations 7 Summer Chapels 14 Chapels of Institutions 14 Educational & Charitable Institutions 15 Clergy in the Order of Canonical Residence 16 Lay Delegates Attending Convention 27 Minutes of the 228th Annual Convention Friday 32 Saturday 36 Supporting Documents Resolutions 40 Reports to Convention 42 Bishop’s Address 59 Episcopal Acts 62 Budget 65 Parochial Membership Statistics 79 Parochial Financial Statistics 85 1 Bishop The Rt. Rev. Ian T. Douglas, B.A., M.A., M.Div., Ph.D. Office: 1335 Asylum Ave., Hartford, 06105 Residence: 1 Collins Ln., Essex, 06426 Bishops Suffragan The Rt. Rev. James E. Curry, B.A., M.Div. Office: 1335 Asylum Ave., Hartford, 06105 Residence: 14 Linwold Dr., West Hartford 06107 The Rt. Rev. Laura J. Ahrens, B.A., M.Div., D.Min. Office: 1335 Asylum Ave. Hartford, 06105 Residence: 47 Craigmoor Rd., West Hartford, 06107 Standing Committee Clerical Lay The Rev. Harlon Dalton – 2012 Ms. Danielle Gaherty - 2012 The Rev. Alex Dyer – 2017 Mr. Steven Mullins – 2013 The Rev. Matthew Calkins (Chair) – 2013 Mr. Thom Peters – 2014 The Rev. Joseph Pace – 2014 Ms. Nancy Noyes – 2015 The Rev. Greg Welin – 2015 Mr. Joseph Carroll, Jr. – 2016 The Rev. Richard Maxwell – 2016 General Convention Indianapolis, Indiana 2012 Clerical Deputies Lay Deputies The Rev. -

Divine Glory

Divine Glory Welcome We are so happy you are with us. Please add your voice and heart to the prayers. Help others find a place near you, and greet the person next to you as we prepare to worship together. Please stand and sit as you are able. Children welcome! Nursery care for infants and toddlers 3 and under in the blue room downstairs. Godly Play for children 4 to 12 is in the raspberry room. For pastoral concerns, please contact Susan McEvoy (754-7079). To make changes or additions to the prayer list or to put an announcement in the bulletin contact Diana Anderson (754-2113). Our Service Today is March 3, the Last Sunday after the Epiphany. Our gospel is the story of Jesus’ transfiguration. It is a story richly woven with themes and symbols drawn from Israel’s past and its hopes for the future. Moses and Elijah represent the law and the prophets; while Jesus is praying, divine glory is reflected in his human person. Today is also our Companion Links Sunday. This year we are taking part in a fresh expressions-influenced liturgy from the Diocese of Leicester, England called “Campfire Communion.” In 2015 the Bishop of each of the five Links Dioceses discerned that one Sunday a year would be dedicated to experiencing a typical worship service from one of our dioceses each year. The Diocese of Wyoming is privileged to be linked with the Diocese of Leicester; the Trichy-Tanjore Diocese, Church of South India; Diocese of Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania; and the Diocese of Kiteto, Tanzania. -

December 2, 2018 LIVING CHURCH CATHOLIC EVANGELICAL ECUMENICAL

Rothko’s Icons Remembrance Rutledge’s Advent THE December 2, 2018 LIVING CHURCH CATHOLIC EVANGELICAL ECUMENICAL Waiting for the Light $5.50 Advent livingchurch.org GIFTT IDEASIDEA FROMFRFROM FORWARDFORWWWARDAARD MOVEMENTMOVEOVEEMENT MORERE IDEAS ATAT FORWARDMOVEMENT.ORGFORWARDMOVEMENT.ORG Read samplessammples and purchaseppurch has at ForwardMovement.orgForwrwardMo rdMoovovement.org R EVANGELICAL ECUMENICAL THE LIVING CHURCH THIS ISSUE December 2, 2018 ON THE COVER | “The uniqueness of Advent is that it really forces us more than any other season to NEWS look deeply into what is wrong in the world” 4 What We Remember on Remembrance Day (see “Advent Begins in the Dark,” p. 16). By Matthew Townsend Advent livingchurch.org Lawrence Lew, OP/Flickr photo 6 Christmas and Humility in Los Posadas By G. Jeffrey MacDonald 8 Bishop Love’s Lone Stance on Same-sex Marriage Analysis by Kirk Petersen FEATURES 16 Fleming Rutledge: “Advent Begins in the Dark” By Zachary Guiliano 19 Past and Future Meet in Advent | By Lawrence N. Crumb CULTURES 20 Rothko’s Icons | By Dennis Raverty BOOKS 4 22 O Wisdom | Review by Emily Hylden 23 The Oxford History of Anglicanism, Volume III 20 Review by Peter Doll OTHER DEPARTMENTS 24 People & Places 26 Sunday’s Readings LIVING CHURCH Partners We are grateful to St. Matthew’s Church, Richmond, and Grace Church Broadway [p. 24], the Diocese of Dallas [p. 25], and St. George’s Church, Nashville [p. 27], whose generous support helped make this issue possible. THE LIVING CHURCH is published by the Living Church Foundation. Our historic mission in the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion is to seek and serve the Catholic and evangelical faith of the one Church, to the end of visible Christian unity throughout the world. -

2021 DIOCESAN/ANGLICAN CYCLE of PRAYER January 3, 2021 Through May 16, 2021

2021 DIOCESAN/ANGLICAN CYCLE OF PRAYER January 3, 2021 through May 16, 2021 JANUARY 2021 3 - Second Sunday after Christmas St. Andrew’s, Shippensburg Psalm: 84 or 84: 1-8 Jeremiah 31: 7-14 Ephesians 1: 3-6,15-19a Pray for The Province of Sudan The Most Rev. Ezekiel Kondo, Archbishop; and for the Province of South Sudan The Most Rev. Justin Arama, Archbishop, and his wife, Joyce 10 - First Sunday after the Epiphany Church of the Resurrection Episcopal Mission – Mt. Carmel Psalm: 29 Genesis 1: 1-5 Acts 19: 1-7 Pray for the Diocese of San Joaquin Bishop Eric Menees and his wife, Florence 17 - Second Sunday after The Epiphany St. Andrew’s, State College Psalm: 139: 1-5, 12-17 Samuel 3: 1-10(11-20) 1 Corinthians 6: 12-20 Pray for the College of Bishops Meeting, January 6 – 10th. 24 - Third Sunday after The Epiphany St. Matthew’s, Sunbury Psalm: 62: 6-14 Jonah 3: 1-5, 10 I Corinthians 7: 29-31 Pray for the Anglican Network in Canada Bishop Charles Masters and his wife, Judy Bishop Don Harvey and his wife, Trudy Bishop Trevor Walters and his wife, Dede Bishop Malcolm Harding and his wife, Marylou Bishop Andy Lines and his wife, Mandy Bishop Stephen Leung and his wife, Nona Bishop Ron Ferris and his wife, Jan 31 - Fourth Sunday after the Epiphany St. Paul’s, Manheim Psalm 111 Deuteronomy 18: 15-20 1 Corinthians 8: 1-13 Pray for the Diocese of the Central States Bishop Peter Manto and his wife, Janice FEBRUARY 2021 7 - Fifth Sunday after The Epiphany Holy Trinity, Hollidaysburg and St. -

General Synod

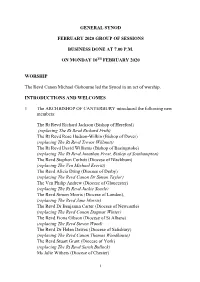

GENERAL SYNOD FEBRUARY 2020 GROUP OF SESSIONS BUSINESS DONE AT 7.00 P.M. ON MONDAY 10TH FEBRUARY 2020 WORSHIP The Revd Canon Michael Gisbourne led the Synod in an act of worship. INTRODUCTIONS AND WELCOMES 1 The ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY introduced the following new members: The Rt Revd Richard Jackson (Bishop of Hereford) (replacing The Rt Revd Richard Frith) The Rt Revd Rose Hudson-Wilkin (Bishop of Dover) (replacing The Rt Revd Trevor Willmott) The Rt Revd David Williams (Bishop of Basingstoke) (replacing The Rt Revd Jonathan Frost, Bishop of Southampton) The Revd Stephen Corbett (Diocese of Blackburn) (replacing The Ven Michael Everitt) The Revd Alicia Dring (Diocese of Derby) (replacing The Revd Canon Dr Simon Taylor) The Ven Philip Andrew (Diocese of Gloucester) (replacing The Rt Revd Jackie Searle) The Revd Simon Morris (Diocese of London), (replacing The Revd Jane Morris) The Revd Dr Benjamin Carter (Diocese of Newcastle) (replacing The Revd Canon Dagmar Winter) The Revd Fiona Gibson (Diocese of St Albans) (replacing The Revd Steven Wood) The Revd Dr Helen Dawes (Diocese of Salisbury) (replacing The Revd Canon Thomas Woodhouse) The Revd Stuart Grant (Diocese of York) (replacing The Rt Revd Sarah Bullock) Ms Julie Withers (Diocese of Chester) 1 (replacing The Reverend Lucy Brewster) Mrs Siân Kellogg (Diocese of Derby) (replacing Mrs Rachel Bell) Mr Rhodri Williams (Diocese of Derby) (replacing Mrs Hannah Grivell) Mr Richard Denno, (Diocese of Liverpool) (replacing Dr David Martlew) The Revd Michael Smith, Diocese of Oxford (replacing -

The First Sunday in Lent

The First Sunday in Lent 1st of March, 2020 Welcome On behalf of everyone at St. John’s, Toorak, a very warm welcome to this church and faith community. St. John’s welcomes everyone to all services and events, regardless of age, gender, sexual orientation, race or background. This is a wonderful and historic church, founded in 1859, a faithful Christian presence for over 160 years! We are part of the Anglican Church of Australia and a member of the global Anglican Communion, comprised of 80 million people. Regular services of worship are held each Sunday at 8am and 10am, and Wednesday at 7pm. All are welcome. Services are followed by times of fellowship over food and drinks to which everyone is also welcome. This church actively follows Jesus’ command to love God, love one’s neighbour and to care for all people. Our clergy and parishioners regularly visit the sick, home-bound, and the dying. We care for the poor and needy through service and charitable giving, through our Opportunity Shop run in partnership with the local Catholic and Uniting churches, and by supporting the work of Anglicare, The Brotherhood of St. Laurence and The Anglican Board of Mission. Our clergy regularly baptise new members of the church, preside at weddings and care for the grieving through our funeral ministry. If we can be of service to you or your family, please do not hesitate to get in touch. If you would like to give of your time and talents in the service of others, please also contact the church and we will gladly welcome your contribution. -

Prayer Diary

JANUARY - MARCH 2020 PRAYER DIARY Launde Abbey is a retreat house in the heart of the country with God at its centre January - April 2020 Retreats at Launde Abbey For more information and to book MAKING CHURCH CONFLICT CREATIVE please call or see our website Led by David Newman and Louise Corke 13th-14th January Launde Abbey, East Norton, Leicestershire, LE7 9XB GROWING UP INTO THE CHILDREN OF GOD Led by David Newman 14th-16th February DEEPENING DISCIPLESHIP: THE ENIGMA OF FORGIVENESS Led by Stephen Cherry 17th February THE CONTEMPLATIVE HEART Led by Ian Cowley 17th-20th February LIVING WITH LOSS Led by Abi and John May 17th-21st February LENT RETREAT: SEASONED BY SEASONS Led by Michael Mitton 9th-12th March POST BEGINNERS RETREAT Led by Helen Newman and Cathy Davies 13th-16th March HOLY WEEK RETREAT: CARRYING DEATH, REVEALING LIFE Led by David and Helen Newman 6th-9th April TAIZÉ EASTER RETREAT Led by Cathy Davies and Emily Walker 14th-17th April © Matt Musgrave Serving the Dioceses of Leicester and Peterborough www.laundeabbey.org.uk • 01572 717254 • [email protected] • Charity No: 1140918 FOREWORD FROM THE BISHOP OF LOUGHBOROUGH The idea of Lent as Jesus faces temptation journeying is a and eventually turns his face towards noble and age the cross. old Christian tradition which Journeys may sometimes be about a acknowledges physical move to pastures new but often that in faith we they are an internal activity. As well as seldom stand having our eyes on that which lies ahead still. Rather, we and draws us forward, to journey well are called to means being aware of the past and all be ever on the that has shaped us and being rooted in move, always the present and all that God is doing now. -

The Communion' 177 7.4 Revision in Synod 183 7.5 Comments and Reactions 191 7.6 Series 3 in Summary 197 Notes 199

Durham E-Theses The revision of the Eucharist in the Church of England : a study of liturgical change in the twentieth century. Lloyd, Edward Gareth How to cite: Lloyd, Edward Gareth (1997) The revision of the Eucharist in the Church of England : a study of liturgical change in the twentieth century., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1049/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Revision of the Eucharist in the Church of England A study of Liturgical Change in the Twentieth Century Edward Gareth Lloyd MA submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of Theology December 1997 The Revision of the Eucharist in the Church of England: A Study of Liturgical Change in the Twentieth Century Edward Gareth Lloyd MA ABSTRACT The Church of England has experienced two substantial periods of liturgical revisior during this century, spanning between them almost 50 years.