The Western, Media, and Masculinity by Norman M. Gendelman A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Individuation in Aldous Huxley's Brave New World and Island

Maria de Fátima de Castro Bessa Individuation in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Island: Jungian and Post-Jungian Perspectives Faculdade de Letras Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Belo Horizonte 2007 Individuation in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Island: Jungian and Post-Jungian Perspectives by Maria de Fátima de Castro Bessa Submitted to the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras: Estudos Literários in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Mestre em Letras: Estudos Literários. Area: Literatures in English Thesis Advisor: Prof. Julio Cesar Jeha, PhD Faculdade de Letras Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Belo Horizonte 2007 To my daughters Thaís and Raquel In memory of my father Pedro Parafita de Bessa (1923-2002) Bessa i Acknowledgements Many people have helped me in writing this work, and first and foremost I would like to thank my advisor, Julio Jeha, whose friendly support, wise advice and vast knowledge have helped me enormously throughout the process. I could not have done it without him. I would also like to thank all the professors with whom I have had the privilege of studying and who have so generously shared their experience with me. Thanks are due to my classmates and colleagues, whose comments and encouragement have been so very important. And Letícia Magalhães Munaier Teixeira, for her kindness and her competence at PosLit I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Dr. Irene Ferreira de Souza, whose encouragement and support were essential when I first started to study at Faculdade de Letras. I am also grateful to Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the research fellowship. -

Cial Climber. Hunter, As the Professor Responsible for Wagner's Eventual Downfall, Was Believably Bland but Wasted. How Much

cial climber. Hunter, as the professor what proves to be a sordid suburbia, responsible for Wagner's eventual are Mitchell/Woodward, Hingle/Rush, downfall, was believably bland but and Randall/North. Hunter's wife is wasted. How much better this film attacked by Mitchell; Hunter himself might have been had Hunter and Wag- is cruelly beaten when he tries to ner exchanged roles! avenge her; villain Mitchell goes to 20. GUN FOR A COWARD. (Universal- his death under an auto; his wife Jo- International, 1957.) Directed by Ab- anne Woodward goes off in a taxi; and ner Biberman. Cast: Fred MacMurray, the remaining couples demonstrate Jeffrey Hunter, Janice Rule, Chill their new maturity by going to church. Wills, Dean Stockwell, Josephine Hut- A distasteful mess. chinson, Betty Lynn. In this Western, Hunter appeared When Hunter reported to Universal- as the overprotected second of three International for Appointment with a sons. "Coward" Hunter eventually Shadow (released in 1958), he worked proved to be anything but in a rousing but one day, as an alcoholic ex- climax. Not a great film, but a good reporter on the trail of a supposedly one. slain gangster. Having become ill 21. THE TRUE STORY OF JESSE with hepatitis, he was replaced by JAMES. (20th Century-Fox, 1957.) Di- George Nader. Subsequently, Hunter rected by Nicholas Ray. Cast: Robert told reporters that only the faithful Wagner, Jeffrey Hunter, Hope Lange, Agnes Moorehead, Alan Hale, Alan nursing by his wife, Dusty Bartlett, Baxter, John Carradine. whom he had married in July, 1957, This was not even good. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

The Passing of the Mythicized Frontier Father Figure and Its Effect on The

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1991 The ap ssing of the mythicized frontier father figure and its effect on the son in Larry McMurtry's Horseman, Pass By Julie Marie Walbridge Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Walbridge, Julie Marie, "The asp sing of the mythicized frontier father figure and its effect on the son in Larry McMurtry's Horseman, Pass By" (1991). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 66. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The passing of the mythicized frontier father figure and its effect on the son in Larry McMurtry's Horseman, Pass By by Julie Marie Walbridge A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Literature) Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1991 ----------- ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE 7 CHAPTER TWO 1 5 CONCLUSION 38 WORKS CITED 42 WORKS CONSULTED 44 -------- -------· ------------ 1 INTRODUCTION For this thesis the term "frontier" means more than the definition of having no more than two non-Indian settlers per square mile (Turner 3). -

The Naked Spur: Classic Western Scores from M-G-M

FSMCD Vol. 11, No. 7 The Naked Spur: Classic Western Scores From M-G-M Supplemental Liner Notes Contents The Naked Spur 1 The Wild North 5 The Last Hunt 9 Devil’s Doorway 14 Escape From Fort Bravo 18 Liner notes ©2008 Film Score Monthly, 6311 Romaine Street, Suite 7109, Hollywood CA 90038. These notes may be printed or archived electronically for personal use only. For a complete catalog of all FSM releases, please visit: http://www.filmscoremonthly.com The Naked Spur ©1953 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. The Wild North ©1952 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. The Last Hunt ©1956 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. Devil’s Doorway ©1950 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. Escape From Fort Bravo ©1953 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. All rights reserved. FSMCD Vol. 11, No. 7 • Classic Western Scores From M-G-M • Supplemental Liner Notes The Naked Spur Anthony Mann (1906–1967) directed films in a screenplay” and The Hollywood Reporter calling it wide variety of genres, from film noir to musical to “finely acted,” although Variety felt that it was “proba- biopic to historical epic, but today he is most often ac- bly too raw and brutal for some theatergoers.” William claimed for the “psychological” westerns he made with Mellor’s Technicolor cinematography of the scenic Col- star James Stewart, including Winchester ’73 (1950), orado locations received particular praise, although Bend of the River (1952), The Far Country (1954) and The several critics commented on the anachronistic appear- Man From Laramie (1955). -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

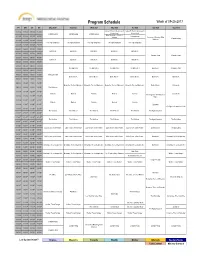

Program Schedule Week of 09-25-2017

Program Schedule Week of 09-25-2017 PT MT CT ET Mon 9/25 Tue 9/26 Wed 9/27 Thu 9/28 Fri 9/29 Sat 9/30 Sun 10/1 James Robison Life Outreach James Robison Life Outreach 03:00A 04:00A 05:00A 06:00A Campmeeting Campmeeting Campmeeting International International Mike Murdock – School of 03:30A 04:30A 05:30A 06:30A Humanitarian Uncommon Blessing: Mike Wisdom Campmeeting Murdock 04:00A 05:00A 06:00A 07:00A The High Chaparral The High Chaparral The High Chaparral The High Chaparral The High Chaparral 04:30A 05:30A 06:30A 07:30A 05:00A 06:00A 07:00A 08:00A Gunsmoke Gunsmoke Gunsmoke Gunsmoke Gunsmoke 05:30A 06:30A 07:30A 08:30A Campmeeting Campmeeting 06:00A 07:00A 08:00A 09:00A Gunsmoke Gunsmoke Gunsmoke Gunsmoke Gunsmoke 06:30A 07:30A 08:30A 09:30A 07:00A 08:00A 09:00A 10:00A The Big Valley The Big Valley The Big Valley The Big Valley Gunsmoke Campmeeting 07:30A 08:30A 09:30A 10:30A 08:00A 09:00A 10:00A 11:00A Hang 'Em High Daniel Boone Daniel Boone Daniel Boone Daniel Boone Gunsmoke Gunsmoke 08:30A 09:30A 10:30A 11:30A 09:00A 10:00A 11:00A 12:00P Bonanza, The Lost Episodes Bonanza, The Lost Episodes Bonanza, The Lost Episodes Bonanza, The Lost Episodes Daniel Boone Gunsmoke 09:30A 10:30A 11:30A 12:30P The Rifleman 10:00A 11:00A 12:00P 01:00P Matlock Matlock Matlock Matlock Matlock Gunsmoke The Virginian: The Men from 10:30A 11:30A 12:30P 01:30P Shiloh 11:00A 12:00P 01:00P 02:00P Matlock Matlock Matlock Matlock Matlock 11:30A 12:30P 01:30P 02:30P Branded Gunfight at Comanche Creek 12:00P 01:00P 02:00P 03:00P The Waltons The Waltons The Waltons -

Mental Math: Estimate Sums and Differences

RETEACH Workbook Grade 4 P Visit The Learning Site! www.harcourtschool.com S H HSP TTitle_CR_NLG4.indditle_CR_NLG4.indd 1 66/7/07/7/07 33:27:56:27:56 PPMM Copyright © by Harcourt, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Permission is hereby granted to individuals using the corresponding student’s textbook or kit as the major vehicle for regular classroom instruction to photocopy entire pages from this publication in classroom quantities for instructional use and not for resale. Requests for information on other matters regarding duplication of this work should be addressed to School Permissions and Copyrights, Harcourt, Inc., 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777. Fax: 407-345-2418. HARCOURT and the Harcourt Logo are trademarks of Harcourt, Inc., registered in the United States of America and/or other jurisdictions. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 13: 978-0-15-356800-8 ISBN 10: 0-15-356800-3 If you have received these materials as examination copies free of charge, Harcourt School Publishers retains title to the materials and they may not be resold. Resale of examination copies is strictly prohibited and is illegal. Possession of this publication in print format does not entitle users to convert this publication, or any portion of it, into electronic format. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 018 6 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 NNL_SEGr4.inddL_SEGr4.indd template1template1 66/7/07/7/07 33:04:36:04:36 PPMM Unit 1: UNDERSTAND WHOLE NUMBERS Unit 2: MULTIPLICATION AND DIVISION AND OPERATIONS FACTS Chapter 1: Understand Place Value Chapter 4: Multiplication and Division Facts 1.1 Place Value Through 4.1 Algebra: Relate Hundred Thousands ............RW1 Operations .................... -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

The-Way-Into-The-Holiest-FB-Meyer

The Way Into the Holiest by F. B. Meyer Christian Classics Ethereal Library About The Way Into the Holiest by F. B. Meyer Title: The Way Into the Holiest URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/meyer/into_holiest.html Author(s): Meyer, F.B. (1847-1929) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Rights: Copyright Christian Classics Ethereal Library Date Created: 2000-07-09 CCEL Subjects: All; Bible; LC Call no: BS2775 LC Subjects: The Bible New Testament Special parts of the New Testament The Way Into the Holiest F. B. Meyer Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii THE WAY INTO THE HOLIEST:. p. 1 PREFACE.. p. 1 I. THE WORD OF GOD.. p. 2 II. THE DIGNITY OF CHRIST. p. 6 III. THE GLORY OF CHRIST©S OFFICE. p. 8 IV. DRIFTING. p. 12 V. ªWHAT IS MAN?º. p. 16 VI. ªPerfect through sufferingsº. p. 20 VII. THE DEATH OF DEATH. p. 23 VIII. CHRIST©S MERCIFUL AND FAITHFUL HELP. p. 26 IX. A WARNING AGAINST UNBELIEF. p. 30 X. THE GOSPEL OF REST. p. 36 XI. THE WORD OF GOD AND ITS EDGE. p. 40 XII. TIMELY AND NEEDED HELP. p. 44 XIII. GETHSEMANE. p. 48 XIV. IMPOSSIBLE TO RENEW TO REPENTANCE . p. 53 XV. THE ANCHORAGE OF THE SOUL.. p. 56 XVI. THE PRIESTHOOD OF CHRIST. p. 60 XVII. THE SUPERLATIVE GREATNESS OF CHRIST. p. 63 XVIII. THE TRUE TABERNACLE . p. 67 XIX. THE TWO COVENANTS. p. 71 XX. THE HEAVENLY THINGS THEMSELVES.. p. 75 XXI. TEACHING BY CONTRAST. p. 79 XXII. THE BLOOD OF CHRIST. -

Paradoxes of the Heart and Mind: Three Case Studies in White Identity, Southern Reality, and the Silenced Memories of Mississippi Confederate Dissent, 1860-1979

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2021 Paradoxes of the Heart and Mind: Three Case Studies in White Identity, Southern Reality, and the Silenced Memories of Mississippi Confederate Dissent, 1860-1979 Billy Loper Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Loper, Billy, "Paradoxes of the Heart and Mind: Three Case Studies in White Identity, Southern Reality, and the Silenced Memories of Mississippi Confederate Dissent, 1860-1979" (2021). Master's Theses. 825. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/825 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARADOXES OF THE HEART AND MIND: THREE CASE STUDIES IN WHITE IDENTITY, SOUTHERN REALITY, AND THE SILENCED MEMORIES OF MISSISSIPPI CONFEDERATE DISSENT, 1860-1979 by Billy Don Loper A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Humanities at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by: Susannah J. Ural, Committee Chair Andrew P. Haley Rebecca Tuuri August 2021 COPYRIGHT BY Billy Don Loper 2021 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT This thesis is meant to advance scholars understanding of the processes by which various groups silenced the memory of Civil War white dissent in Mississippi.