Analytical Digest Russian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application for a Construction License Pursuant to Section 18 of the Nuclear Energy Act (990/1987) for the Hanhikivi 1 Nuclear Power Plant”

March 2016 Comments on the “Application for a Construction License pursuant to Section 18 of the Nuclear Energy Act (990/1987) for the Hanhikivi 1 Nuclear Power Plant” Construction of Leningrad Nuclear Power Plant (VVER-1200) Source: wikimapia.org K. Gufler N. Arnold S. Sholly N. Müllner Prepared for Greenpeace Finland Comments on the Application for a Construction License for the Hanhikivi 1 NPP Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. REQUIREMENTS ................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.1. NUCLEAR ENERGY ACT, SECTION 18 - CONSTRUCTION OF A NUCLEAR FACILITY HAVING CONSIDERABLE GENERAL SIGNIFICANCE ........ 3 2.2. NUCLEAR ENERGY ACT, SECTION 19 – CONSTRUCTION OF OTHER NUCLEAR FACILITIES ............................................................. 3 2.3. NUCLEAR ENERGY DECREE (161/1988) SECTION 32 ........................................................................................................ 4 3. FORMAL COMPLETENESS CHECK ........................................................................................................................ 6 4. DISCUSSION ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 4.1. INFORMATION ABOUT FENNOVOIMA ............................................................................................................................. -

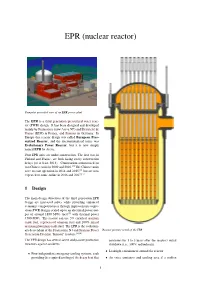

EPR (Nuclear Reactor)

EPR (nuclear reactor) Computer generated view of an EPR power plant The EPR is a third generation pressurized water reac- tor (PWR) design. It has been designed and developed mainly by Framatome (now Areva NP) and Électricité de France (EDF) in France, and Siemens in Germany. In Europe this reactor design was called European Pres- surized Reactor, and the internationalized name was Evolutionary Power Reactor, but it is now simply named EPR by Areva. Four EPR units are under construction. The first two, in Finland and France, are both facing costly construction delays (to at least 2018). Construction commenced on two Chinese units in 2009 and 2010.[1] The Chinese units were to start operation in 2014 and 2015,[2] but are now expected to come online in 2016 and 2017.[3] 1 Design The main design objectives of the third generation EPR design are increased safety while providing enhanced economic competitiveness through improvements to pre- vious PWR designs scaled up to an electrical power out- put of around 1650 MWe (net)[4] with thermal power 4500 MWt. The reactor can use 5% enriched uranium oxide fuel, reprocessed uranium fuel and 100% mixed uranium plutonium oxide fuel. The EPR is the evolution- ary descendant of the Framatome N4 and Siemens Power Reactor pressure vessel of the EPR Generation Division “Konvoi” reactors.[5][6] The EPR design has several active and passive protection continues for 1 to 3 years after the reactor’s initial measures against accidents: shutdown (i.e., 300% redundancy) • Leaktight containment around the reactor -

Finland Project Management Roundup Vol

PM World Journal (ISSN: 2330-4480) Finland Project Management Roundup Vol. X, Issue IX – September 2020 Jouko Vaskimo www.pmworldjournal.net Regional Report Finland Project Management Roundup By Jouko Vaskimo Senior Contributing Editor & International Correspondent Espoo, Finland INTRODUCTION This roundup continues the coverage of Project Management Association Finland, PMI Finland Chapter and some of the key projects currently going on in Finland. PROJECT MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION FINLAND Project Management Association Finland (PMAF), Projektiyhdistys ry in Finnish, is a not-for-profit organization, and the International Project Management Association (IPMA) Member Association (MA) in Finland. Founded in 1978, PMAF promotes the interaction, project-oriented thinking, and exchange and development of practical and theoretical knowledge among project management professionals with over 4000 individual and 200 organizational members. PMAF promotes the development and dissemination of project and project management knowledge. PMAF members are able to enjoy information sharing, workgroups, development projects, project management forums, conferences and certification services PMAF provides. PMAF organizes two annual conferences: Projektipäivät in early November and 3PMO in early June. Due to COVID-19 pandemic PRY organized 2020 3PMO event virtually on 25.8.2020. Projektipäivät is scheduled for 21.10.2020. Please navigate to www.pry.fi/en , https://www.oppia.fi/events/3pmo2020/ and www.projektipaivat.fi for general information on PMAF and its annual events. © Jouko Vaskimo 2020 www.pmworldlibrary.net Page 1 of 6 PM World Journal (ISSN: 2330-4480) Finland Project Management Roundup Vol. X, Issue IX – September 2020 Jouko Vaskimo www.pmworldjournal.net Regional Report PMI FINLAND CHAPTER PMI Finland Chapter is a not-for-profit organization providing project practitioners in Finland continuous learning, networking and community support. -

1 Update to the Construction License Application for The

Update to the Construction License Application for the Hanhikivi 1 nuclear power plant 1 2 Content Update to the construction license application for the Hanhikivi 1 nuclear power plant Updating the application 4 Applicant 4 Project 4 Decisions-in-Principle 4 Plant site 5 Schedule and manner of implementation 6 Organization and expertise 6 Financial resources 7 Nuclear power plant type 9 Security and emergency preparedness arrangements 10 Nuclear fuel management 11 Nuclear waste management 11 Submitting construction license application documentation to the Radiation and Nuclear 12 Safety Authority Appendices 1. Supplementary account of the environmental impact of the construction and operation of the nuclear power plant, as well as of measures to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts (Original Appendix 3A of the Construction License Application submitted to the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment in June 2015) 2. Supplementary account of the environmental impact of the nuclear power plant on the marine environment and fishery during operation (Original Appendix 3B of the Construction License Application submitted to the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment in June 2015) Update to the Construction License Application for the Hanhikivi 1 nuclear power plant 3 Updating the application On 30 June 2015, Fennovoima submitted to the Government an application on the con-struction of a new nuclear power plant on the Hanhikivi peninsula in Pyhäjoki. Since then, the project has progressed and the boundary conditions affecting it have changed. These changes do not change the basis of the project from the decision-in-principle phase, but they do supplement the information presented in the construction license application submitted on 30 June 2015. -

Fennovoima Ltd STATEMENT 7131/815/ 2008 Salmisaarenaukio 1 7.5.2008 00180 HELSINKI

Fennovoima Ltd STATEMENT 7131/815/ 2008 Salmisaarenaukio 1 7.5.2008 00180 HELSINKI ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROGRAMME FOR FENNOVOIMA LTD'S NUCLEAR POWER PROJECT; STATEMENT BY THE CONTACT AUTHORITY On 30 January 2008, Fennovoima Ltd submitted an environmental impact assessment programme (the EIA programme) to the Ministry of Employment and the Economy (hereinafter the MEE) in accordance with the environmental assessment procedure (the EIA procedure), pursuant to the Environmental Impact Assessment Act (468/1994; EIA Act), on a nuclear power project. Prepared by the organisation responsible for the project, the EIA programme presents a plan for the necessary studies and implementation of the EIA procedure. The EIA programme also includes a description of the present state of the environment in the area likely to be affected. Pursuant to the EIA Act, the MEE will act as the contact authority in the EIA procedure. A public notice announcing the launch of the EIA procedure was published on 5 and 7 February 2008 in the following newspapers: Helsingin Sanomat and Hufvudstadsbladet, and the following regional newspapers: Kristiinankaupunki area; Ilkka, Pohjalainen, Suupohjan Sanomat, Syd-Österbotten, Vasabladet and Satakunnan Kansa; Pyhäjoki area; Kalajokilaakso, Keskipohjanmaa, Pyhäjokiseutu, Raahelainen, Raahen Seutu, Vieskalainen; Ruotsinpyhtää area; Borgåbladet, Uusimaa, Kymen Sanomat, Loviisan Sanomat, Östra Nyland – Kotka Nyheter, Etelä-Suomen Sanomat; Simo area; Kaleva, Lounais-Lappi, Meri-Lapin Helmi, Pohjolan Sanomat. The public -

Application for a Construction License Pursuant to Section 18 of The

Application for a Construction License pursuant to Section 18 of the Application for a Construction License pursuant to Section 18 of the Nuclear Energy Act (990/1987) for the Hanhikivi 1 Nuclear Power Plant 1 Nuclear Power the Hanhikivi for (990/1987) pursuant a Construction License to SectionAct Application for 18 of the Nuclear Energy Nuclear Energy Act (990/1987) for the Hanhikivi 1 Nuclear Power Plant June 2015 Updated August 5, 2015 Application for a Construction License pursuant to Section 18 of the Nuclear Energy Act (990/1987) for the Hanhikivi 1 Nuclear Power Plant June 2015 Updated August 5, 2015 Content Construction License Application for Hanhikivi 1 nuclear power plant Application 8 Applicant 8 Project 8 Decisions-in-principle 9 Plant site 9 Schedule and manner of implementation 10 Organization and expertise 11 Financial resources 11 Nuclear power plant type 12 Security arrangements 12 Nuclear fuel management 13 Nuclear waste management 13 Submitting construction license materials to STUK 14 Fulfillment of the prerequisites for granting a construction license, and enforceability of the license decision 14 Appendices Information about Fennovoima 1A Fennovoima Ltd trade register extract, articles of association and shareholder register 17 Summary 18 1B Fennovoima’s ownership base 21 Summary 22 Ownership structure of Fennovoima 23 1C A description of the financial resources and economic viability of Fennovoima’s 25 nuclear power plant project, and the project’s cost estimate and financing plan Summary 26 Financial resources -

Fennovoima's Year 2020 Report

Fennovoima's year 2020 Contents 2020 – A YEAR OF STEADY PROGRESS ....................................4 IMPLEMENTATION QUALITY .......................................................32 Strategy and program Towards high-quality construction of the plant Towards building the power plant Supply chain management PLANT SAFETY .....................................................................................9 OPERATIONAL READINESS ......................................................... 38 We demonstrate the safety of the plant Preparing for the 60-year operation of the plant Key safety assessments Plant availability Significant safety improvements Fractured zone and the plant location PEOPLE AND COMPETENCE ....................................................... 44 Progress made in the key development areas identified Learning organization in STUK’s preliminary safety assessment High personnel wellbeing Nuclear waste management FINANCIAL STATUS AND GOVERNANCE .............................. 49 CONSTRUCTION READINESS .......................................................17 Financial figures Fennovoima prepares for construction of the power plant Risk overview Design progress Responsible business practices Progress in licensing Occupational health and safety REPORTING PRINCIPLES .............................................................. 54 Environment Local impact of the Hanhikivi 1 project 2 CEO's Review and Strategy “We have a clear vision for the future and comprehensive plans for how we will proceed with the project.” 4 CEO’S REVIEW -

The World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2017 Foreword by S

THE WORLD A Mycle Schneider Consulting Project Paris, September 2017 NUCLEAR INDUSTRY STATUS REPORT 2017 World Nuclear Industry Status Report | 2017 | 2 The World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2017 Foreword by S. David Freeman By Mycle Schneider Independent Consultant, Paris, France Project Coordinator and Lead Author Antony Froggatt Independent Consultant, London, U.K. Lead Author With Julie Hazemann Director of EnerWebWatch, Paris, France Documentary Research, Modelling and Datavisualization Tadahiro Katsuta Associate Professor, School of Law, Meiji University, Tokyo, Japan Contributing Author M.V. Ramana Simons Chair in Disarmament, Global and Human Security with the Liu Institute for Global Issues at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada Contributing Author Juan C. Rodriguez Equity Analyst, AlphaValue, Paris, France Contributing Author Andreas Rüdinger Independent Consultant, Paris, France Contributing Author Agnès Stienne Artist, Graphic Designer, Cartographer, Le Mans, France Graphic Design & Layout Paris, September 2017 – A ©Mycle Schneider Consulting Project The cover page was designed by Agnès Stienne. The picture below the solar panel is based on a photography of the Juragua site in Cuba, where building of two Russian-designed 413 MW reactors started in 1983 and was abandoned in 1992. Photography by © Darmon Richter – August 2014. World Nuclear Industry Status Report | 2017 | 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The project coordinator wishes to thank Antony Froggatt, all-time key contributor to this project. Many thanks also to contributing authors Tadahiro Katsuta and M.V. Ramana for their renewed professional contributions. Pleasure to work with you. We are happy to welcome Juan C. Rodriguez and Andreas Rüdinger to the team of contributing authors. Their particular expertise is highly appreciated. -

Society, Environment and Human Security in the Arctic Barents Region

Society, Environment and Human Security in the Arctic Barents Region The Arctic-Barents Region is facing numerous pressures from a variety of sources, including the effect of environmental changes and extractive industrial developments. The threats arising out of these pressures result in human security challenges. This book analyses the formation, and promotion, of societal security within the context of the Arctic-Barents Region. It applies the human security framework, which has increasingly gained currency at the UN level since 1994 (UNDP), as a tool to provide answers to many questions that face the Barents population today. The study explores human security dimensions such as environmental security, economic security, health, food, water, energy, communities, political security and digital security in order to assess the current challenges that the Barents population experiences today or may encounter in the future. In doing so, the book develops a comprehensive analysis of vulnerabilities, challenges and needs in the Barents Region and provides recommendations for new strategies to tackle insecurity and improve the wellbeing of both indigenous and local communities. This book will be a valuable tool for academics, policy-makers and students interested in environmental and human security, sustainable development, environmental studies and the Arctic and Barents Region in particular. Kamrul Hossain is a Research Professor and Director of the Northern Institute for Environmental and Minority Law, University of Lapland. Dorothée Cambou -

Nuclear Energy and the Current Security Environment in the Era of Hybrid Threats

Research Report Nuclear energy and the current security environment in the era RESEARCH AND ANALYISIS RESEARCH of hybrid threats 86/57/0/16 Research Report Nuclear energy and the current security environment in the era of hybrid threats 86/57/0/16 Hybrid CoE Research Reports are thorough, in-depth studies commissioned by Hybrid CoE, or products of joint Hybrid CoE projects. These reports aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of issues relevant to hybrid threats. They either provide relevant policy recommendations or other practical conclusions, and include new research with relevant references. Hybrid CoE provides feedback on the reports before their publication. The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats tel. +358 400 253800 www.hybridcoe.fi ISBN 978-952-7282-24-3 October 2019 Hybrid CoE is an international hub for practitioners and experts, building member states’ and institutions’ capabilities and enhancing EU-NATO cooperation in countering hybrid threats located in Helsinki, Finland. Preface With the rising prominence and increased under- includes cost-effective solutions to support military standing of hybrid threats, it can be foreseen that requirements, energy efficiency in the operational those seeking to challenge democratic states will field, and interaction with academia and industry look for new ways to deploy national power to (ENSEC COE, 2019). further their own strategic interests. Could nuclear Insights into the cyber field were provided by energy be used as one of the strategic tools in the NATO accredited Cooperative Cyber Defence hybrid threat activity for geopolitical aims? As this Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE), established in question has received insufficient attention to date, 2008. -

Download PDF (101.6

JOBNAME: Tynkkynen PAGE: 1 SESS: 5 OUTPUT: Tue Nov 12 09:18:02 2019 4. Energy as international power: the case of Russian–Finnish energy trade In this chapter, I will focus on energy power in action in the trans-border context. Geopolitical power sought by the Russian hydrocarbon culture relies on a similar discipline–reward apparatus as that used domestically by the oil- and gas-inspired geo-governmentality of Putin’s Russia. Then again, in the international setting we witness a much wider repertoire of strategies combining these alluring and coercive means. Russian–Finnish energy trade is an interesting case of energy power, because it leans on the soft approach and builds on goodwill. Although it is well-veiled and spoken of and performed indirectly, the coercive is still present even in this highly ‘neutral’ political atmosphere. Both strategies are an elemen- tary part of the practices and discourses of the Russian hydrocarbon culture, yet one might think that the ‘nuclear diplomacy’ that has recently dominated the Russian–Finnish energy scene is a departure from hydro- carbons. I will demonstrate that the opposite is true. ENERGY AS ‘BUSINESS ONLY’ AND ‘A WEAPON’ Since the mid-2000s, when oil prices rose steadily, President Putin consolidated his grip on power and a growing share of Russian oil production fell into the hands of the state, some scholars have begun to argue that Russia is emerging as an ‘energy superpower’ (Goldman 2008, pp. 7–10, 206–7; Rutland 2015; Smith Stegen 2011, p. 6506), especially in relation to the main buyers of its energy: the EU countries. -

SAFIR2014. the Finnish Research Programme on Nuclear Power

NOL CH OG E Y T • • R E E C S N E E A I 80 R C C S H • S H N I G O I H S L I I V G • H S T SAFIR2014 The Finnish Research Programme on Nuclear Power Plant Safety 2011–2014 Interim Report VTT TECHNOLOGY 80 SAFIR2014 The Finnish Research Programme on Nuclear Power Plant Safety 2011–2014 Interim Report Kaisa Simola (ed.) ISBN 978-951-38-7918-1 (Soft back ed.) ISBN 978-951-38-7919-8 (URL: http://www.vtt.fi/publications/index.jsp) VTT Technology 80 ISSN-L 2242-1211 ISSN 2242-1211 (Print) ISSN 2242-122X (Online) Copyright © VTT 2013 JULKAISIJA – UTGIVARE – PUBLISHER VTT PL 1000 (Tekniikantie 4 A, Espoo) 02044 VTT Puh. 020 722 111, faksi 020 722 7001 VTT PB 1000 (Teknikvägen 4 A, Esbo) FI-02044 VTT Tfn +358 20 722 111, telefax +358 20 722 7001 VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland P.O. Box 1000 (Tekniikantie 4 A, Espoo) FI-02044 VTT, Finland Tel. +358 20 722 111, fax + 358 20 722 7001 Kopijyvä Oy, Kuopio 2013 SAFIR2014 The Finnish Research Programme on Nuclear Power Plant Safety 2011–2014 Interim Report Kaisa Simola (ed.). Espoo 2013. VTT Technology 80. 447 p. Abstract The Finnish Nuclear Power Plant Safety Research Programme 2011–2014, SAFIR2014, is a 4-year publicly funded national technical and scientific research programme on the safety of nuclear power plants. The programme is funded by the State Nuclear Waste Management Fund (VYR), as well as other key organisations operating in the area of nuclear energy.