Nuclear Energy and the Current Security Environment in the Era of Hybrid Threats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application for a Construction License Pursuant to Section 18 of the Nuclear Energy Act (990/1987) for the Hanhikivi 1 Nuclear Power Plant”

March 2016 Comments on the “Application for a Construction License pursuant to Section 18 of the Nuclear Energy Act (990/1987) for the Hanhikivi 1 Nuclear Power Plant” Construction of Leningrad Nuclear Power Plant (VVER-1200) Source: wikimapia.org K. Gufler N. Arnold S. Sholly N. Müllner Prepared for Greenpeace Finland Comments on the Application for a Construction License for the Hanhikivi 1 NPP Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. REQUIREMENTS ................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.1. NUCLEAR ENERGY ACT, SECTION 18 - CONSTRUCTION OF A NUCLEAR FACILITY HAVING CONSIDERABLE GENERAL SIGNIFICANCE ........ 3 2.2. NUCLEAR ENERGY ACT, SECTION 19 – CONSTRUCTION OF OTHER NUCLEAR FACILITIES ............................................................. 3 2.3. NUCLEAR ENERGY DECREE (161/1988) SECTION 32 ........................................................................................................ 4 3. FORMAL COMPLETENESS CHECK ........................................................................................................................ 6 4. DISCUSSION ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 4.1. INFORMATION ABOUT FENNOVOIMA ............................................................................................................................. -

Survey of Design and Regulatory Requirements for New Small Reactors, Contract No

Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission - R550.1 Survey of Design and Regulatory Requirements for New Small Reactors, Contract No. 87055-13-0356 Final Report - July 3, 2014 RSP-0299 Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission R550.1 Survey of Design and Regulatory Requirements for New Small Reactors, Contract No. 87055-13-0356 Final Report July 3, Released for Brian Gihm 0 Victor Snell Jim Sarvinis Milan Ducic 2014 Use Victor Snell Date Rev. Status Prepared By Checked By Approved By Approved By Client - CNSC H346105-0000-00-124-0002, Rev. 0 Page i © Hatch 2015 All rights reserved, including all rights relating to the use of this document or its contents. Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission - R550.1 Survey of Design and Regulatory Requirements for New Small Reactors, Contract No. 87055-13-0356 Final Report - July 3, 2014 Executive Summary The objectives of this report are to perform a design survey of small modular reactors (SMRs) with near-term deployment potential, with a particular emphasis on identifying their innovative safety features, and to review the Canadian nuclear regulatory framework to assess whether the current and proposed regulatory documents adequately address SMR licensing challenges. SMRs are being designed to lower the initial financing cost of a nuclear power plant or to supply electricity in small grids (often in remote areas) which cannot accommodate large nuclear power plants (NPPs). The majority of the advanced SMR designs is based on pressurized water reactor (PWR) technology, while some non-PWR Generation IV technologies (e.g., gas-cooled reactor, lead-cooled reactor, sodium-cooled fast reactor, etc.) are also being pursued. -

Finland 242 Finland Finland

FINLAND 242 FINLAND FINLAND 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1. General Overview Finland (in Finnish Suomi) is a republic in northern Europe, bounded on the north by Norway, on the east by Russia, on the south by the Gulf of Finland and Estonia, on the south-west by the Baltic Sea and on the west by the Gulf of Bothnia and Sweden. Nearly one third of the country lies north of 2 2 the Arctic Circle. The area of Finland, including 31 557 km of inland water, totals 338 000 km . The terrain is generally level, hilly areas are more prominent in the north and mountains are found only in the extreme north-west. The average July temperature in the capital Helsinki on the southern coast is 17 °C. The February average in Helsinki is about -5.7 °C. The corresponding figures at Sodankylä (Lapland) in the northern Finland are 14.1 °C and -13.6 °C. Precipitation (snow and rain) averages about 460 mm in the north and 710 mm in the south. Snow covers the ground for four to five months a year in the south, and about seven months in the north. Finland has a population of 5.16 million (1998) and average population density of 17 per km2 of land. Historical population data is shown in Table 1. The predicted annual population growth rate between the years 1998 and 2010 is 0.21 %. More than two thirds of the population reside in the southern third of the country. In Finland the total primary energy consumption1 per capita was about 60 % higher than the European Union average (according to 1996 statistics) and about 35 % higher than the OECD average. -

Radioactive Waste Management Programmes in NEA Member Countries

RADIOACTIVE WASTE MANAGEMENT PROGRAMMES IN OECD/NEA MEMBER COUNTRIES HUNGARY NATIONAL NUCLEAR ENERGY CONTEXT Commercial utilisation of nuclear power in Hungary goes back to several decades. The four VVER 440/213 nuclear units of the Paks Nuclear Power Plant were connected to the electricity grid between 1983 and 1987. In 2015 the NPP generated 15.8 TWh of electricity which accounted for 52.7% of the total electricity generated in that year in Hungary. These data are characteristic for the period of time around 2015. In January 2014 the Government of Hungary and the Government of the Russian Federation concluded an agreement on the cooperation in the field of peaceful use of nuclear energy, which was promulgated in the Act II of 2014. Among others, the Agreement includes the cooperation on the establishment of two VVER-1200 type nuclear power plant units at the Paks site, to be commissioned in 2025, and 2026 respectively. The present country profile of Hungary does not cover the spent fuel and radioactive waste management issues of the new units. Components of Domestic Electricity Production 2015 Source: MAVIR Hungarian Independent Transmission Operator Company Ltd. SOURCES, TYPES AND QUANTITIES OF WASTE Waste classification Most of the radioactive waste in Hungary originates from the operation of the Paks NPP, and much smaller quantities are generated by other (rather institutional, non-NPP) users of radioactive isotopes. The following classification scheme is based on Appendix 2 in the Decree 47/2003 (VIII. 8.) of the Minister of Health on certain issues of interim storage and final disposal of radioactive wastes, and on certain radiohygiene issues of naturally occurring radioactive materials concentrated during industrial activity. -

Nuclear Options in Electricity Production-Finnish Experience

6th International Conference on Nuclear Option in Countries with Small • Dubr°Vr HR0600024 Nuclear Option in Electricity Production - Finnish Experience Antti Piirto TVO Nuclear Services Ltd 27160 Olkiluoto, Finland [email protected] Nuclear energy has played a key role in Finnish electricity production since the beginning of the 1980s. The load factors of nuclear power plants have been high, radioactive emissions low and the price of nuclear electricity competitive. In addition, detailed plans exist for the final disposal of nuclear waste as well as for the financing of final disposal, and the implementation of final disposal has already been started with the authorities regulating nuclear waste management arrangements at all levels. Deregulation of the electricity market has meant increasing trade and co-operation, with both the other Nordic countries and the other EU Member States. In May 2002, the Finnish Parliament approved the application for a decision in principle on the construction of the fifth nuclear power plant unit in Finland. In December 2003, Teollisuuden Voima Oy concluded an agreement for the supply of the new nuclear power plant unit with a consortium formed by the French- German Framatome ANP and the German Siemens. The new unit, which will be built at Olkiluoto, is a pressurised water reactor having a net electrical output of about 1600 MW. The total value of the project is ca. 3 billion Euros, including investments connected with the development of infrastructure and waste management. The objective is to connect the new unit to the national grid in 2009. When in operation, the unit will increase the share of nuclear energy of Finnish electricity consumption, currently some 26%, to a little more than one third, and decrease Finnish carbon dioxide emissions by more than 10%. -

Waiting for the Nuclear Renaissance: Exploring the Nexus of Expansion and Disposal in Europe

Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy www.psocommons.org/rhcpp Vol. 1: Iss. 4, Article 3 (2010) Waiting for the Nuclear Renaissance: Exploring the Nexus of Expansion and Disposal in Europe Robert Darst, University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth Jane I. Dawson, Connecticut College Abstract This article focuses on the growing prospects for a nuclear power renaissance in Europe. While accepting the conventional wisdom that the incipient renaissance is being driven by climate change and energy security concerns, we argue that it would not be possible without the pioneering work of Sweden and Finland in providing a technological and sociopolitical solution to the industry’s longstanding “Achilles’ heel”: the safe, permanent, and locally acceptable disposal of high-level radioactive waste. In this article, we track the long decline and sudden resurgence of nuclear power in Europe, examining the correlation between the fortunes of the industry and the emergence of the Swedish model for addressing the nuclear waste problem. Through an in-depth exploration of the evolution of the siting model initiated in Sweden and adopted and successfully implemented in Finland, we emphasize the importance of transparency, trust, volunteerism, and “nuclear oases”: locations already host to substantial nuclear facilities. Climate change and concerns about energy independence and security have all opened the door for a revival of nuclear power in Europe and elsewhere, but we argue that without the solution to the nuclear waste quandary pioneered by Sweden and Finland, the industry would still be waiting for the nuclear renaissance. Keywords: high-level radioactive waste, permanent nuclear waste disposal, nuclear power in Europe, nuclear politics in Finland and Sweden © 2010 Policy Studies Organization Published by Berkeley Electronic Press - 49 - Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, Vol. -

State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom Performance in 2018

State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom Performance in 2018 State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom Performance in 2018 PERFORMANCE OF STATE ATOMIC ENERGY CORPORATION ROSATOM IN 2018 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 7. Development of the Northern Sea Route 94 7.1. ROSATOM's Powers Related to the Development and Operation 97 Report Profile 4 of the Northern Sea Route 7.2. Performance of the Nuclear-Powered Icebreaker Fleet 97 and Development of the Northern Sea Route Chapter 1. Our Achievements 6 About ROSATOM 9 Chapter 8. Effective Management of Resources 100 Key Results in 2018 10 Key Events in 2018 11 8.1. Corporate Governance 102 Address by the Chairman of the Supervisory Board 12 8.2. Risk Management 109 Address by the Director General 13 8.3. Performance of Government Functions 116 Address by a Stakeholder Representative 14 8.4. Financial and Investment Management 119 Financial and Economic Results 15 8.5. ROSATOM's Production System 126 8.6. Procurement Management 128 8.7. Internal Control System 132 Chapter 2. Strategy for a Sustainable Future 16 8.8. Prevention of Corruption and Other Offences 134 2.1. Business Strategy until 2030 18 2.2. Sustainable Development Agenda 23 Chapter 9. Development of Human Potential 136 2.3. Value Creation and Business Model 27 and Infrastructure Chapter 3. Contribution to Global Development 32 9.1. Implementation of the HR Policy 138 9.2. Developing the Regions of Operation 150 3.1. Markets Served by ROSATOM 34 9.3. Stakeholder Engagement 158 3.2. International Cooperation 44 3.3. International Business 52 Chapter 10. -

Finland's Legal Preparedness for International Disaster Response

HOST NATION SUPPORT GUIDELINES Finland’s legal preparedness for international disaster response – Host Nation Support Guidelines Finnish Red Cross 2014 Report on the regulation of the reception of international aid in Finland ECHO/SUB/2012/638451 The report is part of the project titled ”Implementation of the EU Host Nation Support Guidelines”, (ECHO/SUB/2012/638451) The project is funded by the Civil Protection Financial Instrument of the European Union for 2013– 2014, provided by the European Community Humanitarian Office (ECHO) Author: Maarit Pimiä, Bachelor of Laws Mandators: The Finnish Red Cross, National Preparedness Unit The Department of Rescue Services of the Ministry of the Interior Translated by: Semantix Finland Oy Date: 14.3.2014 © Finnish Red Cross The European Commission is not responsible for the content of this report or the views expressed in this report. The authors are responsible for the content. 2 Report on the regulation of the reception of international aid in Finland ECHO/SUB/2012/638451 Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 6 Definitions ............................................................................................................................. 8 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 11 1.1 Background of the report ..................................................................................... -

OECD-IAEA Paks Fuel Project Was Established in 2005 As a Joint Project Between the IAEA and the OECD/NEA

spine: 5.455 mm 81 pages OECD–IAEA Paks Fuel Project Final Report INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY VIENNA 09-2210-PUB-1389-cover.indd 1 2010-06-29 10:12:33 OECD–IAEA PAKS FUEL PROJECT The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GHANA NIGERIA ALBANIA GREECE NORWAY ALGERIA GUATEMALA OMAN ANGOLA HAITI PAKISTAN ARGENTINA HOLY SEE PALAU ARMENIA HONDURAS PANAMA AUSTRALIA HUNGARY PARAGUAY AUSTRIA ICELAND PERU AZERBAIJAN INDIA PHILIPPINES BAHRAIN INDONESIA POLAND BANGLADESH IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PORTUGAL BELARUS IRAQ QATAR BELGIUM IRELAND REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA BELIZE ISRAEL ROMANIA BENIN ITALY RUSSIAN FEDERATION BOLIVIA JAMAICA SAUDI ARABIA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JAPAN SENEGAL BOTSWANA JORDAN SERBIA BRAZIL KAZAKHSTAN SEYCHELLES BULGARIA KENYA SIERRA LEONE BURKINA FASO KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE BURUNDI KUWAIT SLOVAKIA CAMEROON KYRGYZSTAN SLOVENIA CANADA LATVIA SOUTH AFRICA CENTRAL AFRICAN LEBANON SPAIN REPUBLIC LESOTHO SRI LANKA CHAD LIBERIA SUDAN CHILE LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA SWEDEN CHINA LIECHTENSTEIN SWITZERLAND COLOMBIA LITHUANIA SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC CONGO LUXEMBOURG TAJIKISTAN COSTA RICA MADAGASCAR THAILAND CÔTE D’IVOIRE MALAWI THE FORMER YUGOSLAV CROATIA MALAYSIA REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA CUBA MALI TUNISIA CYPRUS MALTA TURKEY CZECH REPUBLIC MARSHALL ISLANDS UGANDA DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC MAURITANIA UKRAINE OF THE CONGO MAURITIUS UNITED ARAB EMIRATES DENMARK MEXICO UNITED KINGDOM OF DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MONACO GREAT BRITAIN AND ECUADOR MONGOLIA NORTHERN IRELAND EGYPT MONTENEGRO UNITED REPUBLIC EL SALVADOR MOROCCO OF TANZANIA ERITREA MOZAMBIQUE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ESTONIA MYANMAR URUGUAY ETHIOPIA NAMIBIA UZBEKISTAN FINLAND NEPAL VENEZUELA FRANCE NETHERLANDS VIETNAM GABON NEW ZEALAND YEMEN GEORGIA NICARAGUA ZAMBIA GERMANY NIGER ZIMBABWE The Agency’s Statute was approved on 23 October 1956 by the Conference on the Statute of the IAEA held at United Nations Headquarters, New York; it entered into force on 29 July 1957. -

Energy in Russia's Foreign Policy Kari Liuhto

Kari Liuhto Energy in Russia’s foreign policy Electronic Publications of Pan-European Institute 10/2010 ISSN 1795 - 5076 Energy in Russia’s foreign policy Kari Liuhto 1 10/2010 Electronic Publications of Pan-European Institute www.tse.fi/pei 1 Kari Liuhto is Professor in International Business (specialisation Russia) and Director of the Pan- European Institute at the Turku School of Economics, University of Turku, Finland. His research interests include EU-Russia economic relations, energy relations in particular, foreign investments into Russia and the investments of Russian firms abroad, and Russia’s economic policy measures of strategic significance. Liuhto has been involved in several Russia-related projects funded by Finnish institutions and foreign ones, such as the Prime Minister’s Office, various Finnish ministries and the Parliament of Finland, the European Commission, the European Parliament, and the United Nations. Kari Liuhto PEI Electronic Publications 10/2010 www.tse.fi/pei Contents PROLOGUE 4 1 INTRODUCTION: HAVE GAS PIPES BECOME A MORE POWERFUL FOREIGN POLICY TOOL FOR RUSSIA THAN ITS ARMY? 5 2 RUSSIA’S ENERGETIC FOREIGN POLICY 8 2.1 Russia’s capability to use energy as a foreign policy instrument 8 2.2 Dependence of main consumers on Russian energy 22 2.3 Russia’s foreign energy policy arsenal 32 2.4 Strategic goals of Russia's foreign energy policy 43 3 CONCLUSION 49 EPILOGUE 54 REFERENCES 56 1 Kari Liuhto PEI Electronic Publications 10/2010 www.tse.fi/pei Tables Table 1 Russia’s energy reserves in the global scene (2008) 9 Table 2 The development of the EU’s energy import dependence 23 Table 3 The EU’s dependence on external energy suppliers 24 Table 4 Share of Russian gas in total primary energy consumption 26 Table 5 Natural gas storage of selected European countries 29 Table 6 Russia’s foreign policy toolbox 32 Table 7 Russia’s disputes with EU member states under Putin’s presidency 36 Table 8 Russia’s foreign energy policy toolbox 40 Table 9 Russia's potential leverage in the ex-USSR (excl. -

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS in NUCLEAR SAFETY in HUNGARY April 2019

1 HI LI HUNGARIAN ATOMIC ENERGY AUTHORITY Nuclear Safety Bulletin H-1539 Budapest, P.O. Box 676, Phone: +36 1 4364-800, Fax: +36 1 4364-883, e-mail: [email protected] website: www.haea.gov.hu RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN NUCLEAR SAFETY IN HUNGARY April 2019 General 2018 annual safety performance assessment of nuclear facilities The HAEA regularly evaluates the safety performance of the operators of nuclear facilities. The main sources of data for the assessment are the regular reports and the event reports of the licensees, the protocols of regulatory inspections including the regular and comprehensive inspections focusing on specific areas, and the reactive inspections. Below we give a short review on the 2018 safety performance assessment. The safety performance data are taken from the quarterly reports of Paks NPP and the semi-annual reports of the other licensees. Paks Nuclear Power Plant Eighteen reportable events occurred in 2018. Eighteen events have been reported by the NPP altogether, all of them were of category „below scale” corresponding to Level-0 on the seven-level International Nuclear Event Scale (INES). 2 There has been no event causing violation of technical operating specification since 2014. On 24 October 2018, the NPP moved to Operating Conditions and Limits (OCL) based on a license by the HAEA. There was no event causing violation of OCL since then. Five automatic reactor protection actuations occurred in 2018. One SCRAM-III and the SCRAM-I actuation were connected to the same event, which was caused by the low water level of steam generators of Unit 3. -

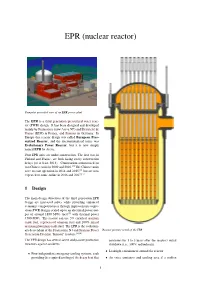

EPR (Nuclear Reactor)

EPR (nuclear reactor) Computer generated view of an EPR power plant The EPR is a third generation pressurized water reac- tor (PWR) design. It has been designed and developed mainly by Framatome (now Areva NP) and Électricité de France (EDF) in France, and Siemens in Germany. In Europe this reactor design was called European Pres- surized Reactor, and the internationalized name was Evolutionary Power Reactor, but it is now simply named EPR by Areva. Four EPR units are under construction. The first two, in Finland and France, are both facing costly construction delays (to at least 2018). Construction commenced on two Chinese units in 2009 and 2010.[1] The Chinese units were to start operation in 2014 and 2015,[2] but are now expected to come online in 2016 and 2017.[3] 1 Design The main design objectives of the third generation EPR design are increased safety while providing enhanced economic competitiveness through improvements to pre- vious PWR designs scaled up to an electrical power out- put of around 1650 MWe (net)[4] with thermal power 4500 MWt. The reactor can use 5% enriched uranium oxide fuel, reprocessed uranium fuel and 100% mixed uranium plutonium oxide fuel. The EPR is the evolution- ary descendant of the Framatome N4 and Siemens Power Reactor pressure vessel of the EPR Generation Division “Konvoi” reactors.[5][6] The EPR design has several active and passive protection continues for 1 to 3 years after the reactor’s initial measures against accidents: shutdown (i.e., 300% redundancy) • Leaktight containment around the reactor