The Crucible of Adversarial Testing: Access to Counsel in Delaware’S Criminal Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRUCTURING the PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe*

STRUCTURING THE PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe* ABSTRACT. The public defender may be critical to protecting individual rights in the U.S. criminal process, but state governments take remarkably different approaches to distributing the services. Some organize indigent defense as a function of the executive branch of state governance. Others administer the services through the judicial branch. The remaining state governments do not place it within any branch of state government, they delegate its management to local counties. This administrative choice has important implications for the public defender’s efficiency and effectiveness. It influences how the public defender will be funded and also the extent to which the public defender, as an institution, will respond to the particular interests of local communities. So, which branch of government should oversee the public defender? Should the public defender exist under the same branch of government that oversees the prosecutor and the police – two entities that the public defender seeks to hold accountable in the criminal process? Should the provision of services be housed under the judicial branch which is ordinarily tasked with being a neutral arbiter in criminal proceedings? Perhaps a public defender who is independent of statewide governance is ideal even if that might render it a lesser player among the many government agencies battling at the state level for limited financial resources. This article answers this question about state assignment by engaging in an original examination of each state’s architectural choices for the public defender. Its primary contribution is to enrich our current understanding of how each state manages the public defender function and how that decision influences the institution’s funding and ability to adhere to ethical and professional mandates. -

Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases by Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report November 2000, NCJ 179023 Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases By Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D. Highlights BJS Statistician At felony case termination, court-appointed counsel represented 82% Almost all persons charged with a of State defendants in the 75 largest counties in 1996 felony in Federal and large State courts and 66% of Federal defendants in 1998 were represented by counsel, either Percent of defendants ù Over 80% of felony defendants hired or appointed. But over a third of Felons Misdemeanants charged with a violent crime in persons charged with a misdemeanor 75 largest counties the country’s largest counties and in cases terminated in Federal court Public defender 68.3% -- 66% in U.S. district courts had represented themselves (pro se) in Assigned counsel 13.7 -- Private attorney 17.6 -- publicly financed attorneys. court proceedings prior to conviction, Self (pro se)/other 0.4 -- as did almost a third of those in local ù About half of large county jails. U.S. district courts Federal Defender felony defendants with a public Organization 30.1% 25.5% defender or assigned counsel Indigent defense involves the use of Panel attorney 36.3 17.4 and three-quarters with a private publicly financed counsel to represent Private attorney 33.4 18.7 Self representation 0.3 38.4 lawyer were released from jail criminal defendants who are unable to pending trial. afford private counsel. At the end of Note: These data reflect use of defense counsel at termination of the case. -

Four Models of the Criminal Process Kent Roach

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 89 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter Winter 1999 Four Models of the Criminal Process Kent Roach Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Kent Roach, Four Models of the Criminal Process, 89 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 671 (1998-1999) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/99/8902-0671 THM JOURNAL OF QMINAL LAW& CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 89, No. 2 Copyright 0 1999 by Northwestem University. School of Law Psisd in USA. CRIMINOLOGY FOUR MODELS OF THE CRIMINAL PROCESS KENT ROACH* I. INTRODUCTION Ever since Herbert Packer published "Two Models of the Criminal Process" in 1964, much thinking about criminal justice has been influenced by the construction of models. Models pro- vide a useful way to cope with the complexity of the criminal pro- cess. They allow details to be simplified and common themes and trends to be highlighted. "As in the physical and social sciences, [models present] a hypothetical but coherent scheme for testing the evidence" produced by decisions made by thousands of actors in the criminal process every day.2 Unlike the sciences, however, it is not possible or desirable to reduce the discretionary and hu- manistic systems of criminal justice to a single truth. -

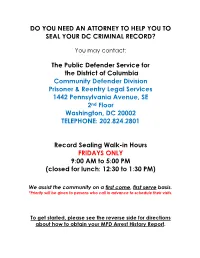

Do You Need an Attorney to Help You to Seal Your Dc Criminal Record?

DO YOU NEED AN ATTORNEY TO HELP YOU TO SEAL YOUR DC CRIMINAL RECORD? You may contact: The Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia Community Defender Division Prisoner & Reentry Legal Services 1442 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE 2nd Floor Washington, DC 20002 TELEPHONE: 202.824.2801 Record Sealing Walk-in Hours FRIDAYS ONLY 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM (closed for lunch: 12:30 to 1:30 PM) We assist the community on a first come, first serve basis. *Priority will be given to persons who call in advance to schedule their visits. To get started, please see the reverse side for directions about how to obtain your MPD Arrest History Report. To Get Started First Obtain Your “MPD Arrest History Report for the Purposes of the Criminal Sealing Act of 2006” Before anyone can determine your eligibility to file a motion to seal records and/or arrests, you need to obtain an MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. Five Steps to Obtain Your MPD Arrest History Report 1. Bring with you ALL of the following items: a. A valid government-issued ID (such as a Driver’s License) b. $7.00 cash or money order to pay for the record c. Your social security number 2. Go to the Record Information Desk at the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), located at 300 Indiana Avenue, NW, Criminal History Section, Room 1075 (On the 1st Floor). a. They are open Mon-Fri from 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 3. Request a copy of your MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. -

Is an Adversarial Legal System Well Suited For

could probably chalk up the results to any number of imperfections—dispro- portionate access to evidence, disparate On Reconsideration advocacy skills, a misunderstood ques- tion, a mis-phrased answer, a key docu- ment that somehow disappeared and nev- IS AN ADVERSARIAL er became part of the evidence, a witness whose distorted memory was persuasively LEGAL SYSTEM WELL communicated and unjustifiably believed, an ambiguous email that created a false SUITED FOR DELIVERING impression, a litigation budget that sank under the weight of crippling discovery, JUSTICE? an arbitrary evidentiary ruling, a confus- ing jury instruction, an unfortunate gap between what someone said and what that person meant, an adjudicator whose hid- KENNETH R. BERMAN den biases led to an erroneous credibility Kenneth R. Berman is a partner at Nutter McClennen & Fish LLP in Boston and the author of Reinventing assessment or a mistaken legal ruling. The Witness Preparation: Unlocking the Secrets to Testimonial Success (ABA 2018). list goes on and on. In an adversarial system, the search for truth is a battle of narratives. The side with the more sympathetic, more plausible story usually wins, even if the truth belongs elsewhere. Generally, our “On Reconsideration.” That’s the banner of narratives, each of which is then put adversary system favors the better story, this new column. Here, we’ll test our as- through intensive questioning and critiqu- not necessarily the truer one. Emotion sumptions about how justice is dispensed, ing by the opposing lawyer, who fires ver- prevailing over logic. how truth is proven, how we litigators are bal cannonballs at everything attackable. -

Individual Access to Constitutional Justice

Strasbourg, 27 January 2011 CDL-AD(2010)039rev. Study N° 538 / 2009 Or. Engl. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) STUDY ON INDIVIDUAL ACCESS TO CONSTITUTIONAL JUSTICE Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 85th Plenary Session (Venice, 17-18 December 2010) on the basis of comments by Mr Gagik HARUTYUNYAN (Member, Armenia) Ms Angelika NUSSBERGER (Substitute Member, Germany) Mr Peter PACZOLAY (Member, Hungary) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. http://www.venice.coe.int CDL-AD(2010)039 - 2 - Table of contents INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................6 GENERAL REMARKS....................................................................................................6 I. ACCESS TO CONSTITUTIONAL REVIEW ...............................................................15 I.1. TYPES OF ACCESS .................................................................................................17 I.1.1. Indirect access...................................................................................................17 I.1.2. Direct access.....................................................................................................20 I.2. THE ACTS UNDER REVIEW ......................................................................................28 I.3. PROTECTED RIGHTS ..............................................................................................29 PARTIAL CONCLUSIONS OF CHAPTER -

Unpacking the Mexican Federal Judiciary: an Inner Look at the Ethos of the Judicial Branch

Esta revista forma parte del acervo de la Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM http://www.juridicas.unam.mx/ https://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx/bjv https://revistas.juridicas.unam.mx/ DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iij.24485306e.2018.1.12511 exican M Review aw New Series L V O L U M E XI Number 1 UNPACKING THE MEXICAN FEDERAL JUDICIARY: AN INNER LOOK AT THE ETHOS OF THE JUDICIAL BRANCH Gabriel FERREYRA* ABSTRACT: Based on 45 interviews conducted in 6 different jurisdictions in Mexico, this article presents a close examination of the distinctive attributes and practices that characterize the Mexican Federal Judiciary (Poder Judicial Fed- eral). Interviewees included typists, clerks and court clerks, judges, and justices, as well as scholars and experts with an in-depth knowledge of this institution. From an insider perspective, the article sheds light on idiosyncrasies, customs, and orga- nizational patterns that are not well known outside the MFJ, such as its strong hierarchical structure, the nature of the work done, employee salaries, the practices of legalism, the risks of drug-related trials, and structural gender inequalities. It also discusses phenomena like influence peddling, cronyism, and nepotism, all of which are widely practiced within the MFJ but kept undisclosed. These practices do not necessarily have a negative connotation within the federal judiciary because they have become normalized due to their widespread use. In fact, the notion of corruption is somehow ambiguous for many judicial employees. Despite all this, the MFJ has become a more professionalized branch where the vast majority of employees performed their job competently and efficiently. -

In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: the Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis V

UIC Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Article 3 Winter 2011 In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) Harvey Gee Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Harvey Gee, In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN ORDER TO BE SILENT, YOU MUST FIRST SPEAK: THE SUPREME COURT EXTENDS DAVIS'S CLARITY REQUIREMENT TO THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT IN BERGHUIS V. THOMPKINS HARVEY GEE* Criminal suspects must now unambiguously invoke their right to remain silent-which, counterintuitively, requires them to speak. .. suspects will be legally presumed to have waived their rights even if they have given clear expression of their intent to do so. Those results ... find no basis in Miranda... 1 I. INTRODUCTION At 3:09 a.m., two police officers escorted Richard Lovejoy, a suspect in an armed bank robbery, into a twelve-foot-square dimly lit interrogation room affectionately referred to as the "boiler room." This room is equipped with a two-way mirror in the wall for viewing lineups. -

A Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System

A GUIDE TO MENTAL ILLNESS AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM A SYSTEMS GUIDE FOR FAMILIES AND CONSUMERS National Alliance on Mental Illness Department of Policy and Legal Affairs 2107 Wilson Blvd., Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201 Helpline: 800-950-NAMI NAMI – Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System FOREWORD Tragically, jails and prisons are emerging as the "psychiatric hospitals" of the 1990s. A sample of 1400 NAMI families surveyed in 1991 revealed that 40 percent of family members with severe mental illness had been arrested one or more times. Other national studies reveal that approximately 8 percent of all jail and prison inmates suffer from severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. These statistics are a direct reflection of the failure of public mental health systems to provide appropriate care and treatment to individuals with severe mental illnesses. These horrifying statistics point directly to the need of NAMI families and consumers to develop greater familiarity with the workings of their local criminal justice systems. Key personnel in these systems, such as police officers, prosecutors, public defenders and jail employees may have limited knowledge about severe mental illness and the needs of those who suffer from these illnesses. Moreover, the procedures, terminology and practices which characterize the criminal justice system are likely to be bewildering for consumers and family members alike. This guide is intended to serve as an aid for those people thrust into interaction with local criminal justice systems. Since criminal procedures are complicated and often differ from state to state, readers are urged to consult the laws and procedures of their states and localities. -

Criminal Procedure Code of the Republic of Armenia

(not official copy) CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA GENERAL PART Section One : GENERAL PROVISIONS CHAPTER 1. LEGISLATION ON CRIMINAL PROCEDURE Article 1. Legislation Governing Criminal Proceedings Article 2. Objectives of the Criminal-Procedure Legislation Article 3. Territory of Effect of the Criminal-procedure Law Article 4. Effect of the Criminal-Procedure Law in the Course of Time Article 5. Peculiarities in the Effect of the Criminal-Procedure Law Article 6. Definitions of the Basic Notions Used in the Criminal-procedure Code CHAPTER 2. PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS Article 7. Legitimacy Article 8. Equality of All Before the Law Article 9. Respect for the Rights, Freedoms and Dignity of an Individual Article 10. Ensuring the Right to Legal Assistance Article 11. Immunity of Person Article 12. Immunity of Residence Article 13. Security of Property Article 14. Confidentiality of Correspondence, Telephone Conversations, Mail, Telegraph and Other Communications Article 15. Language of Criminal Proceedings Article 16. Public Trial Article 17. Fair Trial Article 18. Presumption of Innocence Article 19. The Right to Defense of the Suspect and the Accused and Guarantees for this Right Article 20. Privilege Against Self-Incrimination (not official copy) Article 21. Inadmissibility of Repeated Conviction and Criminal Prosecution for the Same Crime Article 22. Rehabilitation of the Rights of the Persons who suffered from Judicial Mistakes Article 23. Adversarial System of Criminal Proceedings Article 24. Administration of Justice Exclusively by the Court Article 25. Independent Assessment of Evidence CHAPTER 3. CONDUCT OF CRIMINAL CASE Article 26. Conduct of Criminal Case Article 27. The Obligation to institute a criminal case and resolution of the crime Article 28. -

Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin

Marquette Law Review Volume 91 Issue 1 Symposium: Dispute Resolution in Criminal Article 16 Law Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin, 91 Marq. L. Rev. 357 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol91/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PANEL DISCUSSION PLEA BARGAINING FROM THE CRIMINAL LAWYER'S PERSPECTIVE: PLEA BARGAINING IN WISCONSIN* PANELISTS E. Michael McCann FormerDistrict Attorney, Milwaukee County; Boden Teaching Fellow & Adjunct Professor of Law, Marquette UniversityLaw School Michelle Jacobs FirstAssistant United States Attorney, Eastern Districtof Wisconsin Erik Peterson United States Attorney, Western Districtof Wisconsin Dean Strang Hurley, Burish & Stanton, S.C. Nathan Fishbach Whyte Hirschboeck Dudek S. C. Deja Vishny Office of the Wisconsin State Public Defender MODERATOR Daniel D. Blinka Professorof Law, Marquette University Law School This panel discussion was held as part of the Conference on Plea Bargaining on April 14, 2007, at Marquette University Law School. The transcript of the Panel Discussion has been lightly edited. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW [91:357 The primary purpose of the Conference is to present diverse views on plea bargaining. In addition to the articles, which represent varying academic and policy perspectives, we have assembled a panel of criminal law practitioners to contribute their insights and experience. -

Necessity for a Public Defender Mayer C

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 5 | Issue 5 Article 4 1915 Necessity for a Public Defender Mayer C. Goldman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Mayer C. Goldman, Necessity for a Public Defender, 5 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 660 (May 1914 to March 1915) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE NECESSITY FOR A PUBLIC DEFENDER MAYE C. GOLDMAN' Among the grave legal and sociological reforms which are being seriously urged at present by thinking people, there is being actively agitated the important proposition of creating the office of a Public Defender to defend indigent persons accused of crime. If by the establishment of such an office, the standard of our criminal jurisprudence can be raised and the principles of human justice thereby placed upon a more solid foundation, the inevitable result thereof must be, that the suspicion now lurking in the public mind to the effect that a discrimination exists between the rich and the poor, must give way to a wholesome realization of the fact that our much vaunted theory of "equality before the law" has become an actuality-instead of a mere high-sounding phrase. It must be apparent to all, that the important consideration in the trial of any cause, is, (or ought to be) to ascertain the truth- and not a mere contest in which one side or the other is permitted to gain an advantage by superior strategy, skill or power.