A Comparative Study of Four American Professional Wind Bands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gallant Seventh John Philip Sousa

PROGRAM NOTES The Gallant Seventh John Philip Sousa Written during the final decade of his life, The Gallant Seventh is widely considered to be among the composer’s greatest works. Sousa composed this march for the 7th Regiment, 107th Infantry of the New York National SYMPHONIC BAND David Scott, conductor Guard. The conductor of the regiment’s band was Francis W. Sutherland, who had been a member of Sousa’s own band before joining the military Tuesday, October 4, 2016 - 8 p.m. during the First World War. This piece was premiered by an ensemble MEMORIAL CHAPEL consisting of members of both the Sousa band and the 7th Regiment band. The Gallant Seventh (1922) John Philip Sousa Dance of the Jesters Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1854-1932) ed. Frederick Fennell Tchaikovsky experienced a renewed fascination with his Russian nationalism in music following his meeting with fellow Russian composer Dance of the Jesters Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1868. From this point forward, Russian folk (1840-1893) music and dance would become a major driving force in Tchaikovsky’s arr. Ray Cramer compositions. In this piece, you will hear sounds characteristic of his many ballets, his melodic excitement, and his boundless energy. Song of Threnos “A Thenody for Band” (1961) Alfred Reed (1921-2005) Song of Threnos”A Thenody for Band” (1961) Alfred Reed Austin Davis, conductor The word “threnody” comes from the Greek “threnoidia”, which, in turn, is Fortress (1988) Frank Ticheli derived from a combination of two other Greek words, “threnos”, meaning (b. 1958) lament, and “oide”, meaning song. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North! Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9130640 The influence of Leonard B. Smith on the heritage of the band in the United States Polce, Vincent John, Ph.D. -

The GIA Historical Music Series

GIA Publications, Inc. 2018 2018 Music Education Catalog At GIA, we aspire to create innovative resources that communicate the joys of music making and music learning—that delve deeper into what it means to be musical. By working with leading authors who represent the very best the profession has to offer for all levels from preschool through college and beyond, GIA seeks to help music teachers communicate the joy, art, skill, complexity, and knowledge of musicianship. This year we again offer a wide range of new resources for early childhood through college. Scott Edgar explores Music Education and Social Emotional Learning (page 7); the legendary Teaching Music through Performance in Band series moves to Volume 11 (page 8); Scott Rush publishes Habits of a Significant Band Director (page 9) and together with Christopher Selby releases Habits of a Successful Middle Level Musician (pages 10-11). And there’s finally a Habits book for choir directors (page 12). James Jordan gives us four substantial new publications (pages 13-16). There’s also an Ultimate Guide to Creating a Quality Music Assessment Program (page 19). For general music teachers, there is a beautiful collection of folk songs from Bali (page 21), a best- selling book on combining John Feierabend’s First Steps in Music methodology with Orff Schulwerk (page 23), plus the new folk song picture book, Kitty Alone (page 24), just to start. All told, this catalog has 400 pages of resources to explore and enjoy! We’re happy to send single copies of the resources in this catalog on an “on approval” basis with full return privileges for 30 days. -

Cbarber Repertoire 2020.Pdf

Carolyn A. Barber University of Nebraska-Lincoln Conducting Repertoire, 2001-present UNL Wind Ensemble 2020 [April 28 concert cancelled due to COVID-19 precautions on campus] March 11, Kimball Recital Hall Joan Tower, Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman No. 1 (1987) Victoria Bond, The Indispensable Man (2010) *Nebraska premiere performance Felicia Sandler, Rosie the Riveter (2000) *Nebraska premiere performance Jonathan Newman, Symphony No. 1: My Hands Are a City (2009) 2019 December 11, Kimball Recital Hall https://youtu.be/4HBj7rIC6vk Gustav Holst, Suite in E-flat (1909) Percy Grainger, arr. Perna, Mock Morris (1910/2016) Joshua Cutting, doctoral associate conductor J.S. Bach, arr. N. Falcone, Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor (1712/1969) Gustav Holst, Bach’s Fugue à la Gigue (1707/1928) Rubén Gómez, doctoral associate conductor Percy Grainger, Colonial Song (1919/1997) Paul Hindemith, Symphony in B-flat (1951) October 2, Kimball Recital Hall https://youtu.be/RkzJB7msUuY Stephen Montague, Intrada 1631 (2003) Donald Grantham, Circa 1600 (2018) Kathryn Salfelder, Crossing Parallels (2011) Bob Margolis, Terpsichore (1981) Roberto Sierra, arr. Scatterday, Tumbao from Sinfonia No. 3 (2005/2009) *Nebraska premiere performance [Spring semester sabbatical – Newell Scholar at Georgia College] 2018 December 5, Kimball Recital Hall https://youtu.be/OwTWlg7jmiI Larry Tuttle, Across the Divide (2018) Carter Pann, The Three Embraces (2013) Cindy McTee, California Counterpoint: The Twittering Machine (1993) Carter Pann, My Brother’s Brain: A Symphony for Winds (2011) Carter Pann, Floyd’s Fantastic Five-Alarm Foxy Frolic (2009) October 3, Kimball Recital Hall Bernard Rogers, Three Japanese Dances: Dance with Pennons (1933/1956) Jennifer Jolley, The Eyes of the World Are Upon You (2017) *Nebraska premiere performance Frank Ticheli, Amazing Grace (1994) Rubén Gómez, doctoral associate conductor David Maslanka, Symphony No. -

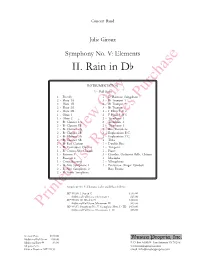

II. Rain in Db

Concert Band Julie Giroux Symphony No. V: Elements II. Rain in Db INSTRUMENTATION 1 - Full Score 1 - Piccolo 1-E Baritone Saxophone 2 - Flute 1A 3-B Trumpet 1 2 - Flute 1B 3-B Trumpet 2 2 - Flute 2A 3-B Trumpet 3 2 - Flute 2B 2 - F Horn 1 & 2 1 - Oboe 1 2 - F Horn 3 & 4 1 - Oboe 2 2 - Trombone 1 2-B Clarinet 1A 2 - Trombone 2 2-B Clarinet 1B 2 - Trombone 3 2-B Clarinet 2A 2 - Bass Trombone 2-B Clarinet 2B 2 - Euphonium B.C. 2-B Clarinet 3A 2 - Euphonium T.C. 2-B Clarinet 3B 4 - Tuba 2-B Bass Clarinet 1 - Double Bass 1-B Contrabass Clarinet 1 - Timpani 1-EPreview Contra Alto Clarinet 1Only - Piano 1 - Bassoon 1 3 - Crotales, Orchestra Bells, Chimes 1 - Bassoon 2 1 - Marimba 1 - Contrabassoon 1 - Vibraphone 2-E Alto Saxophone 1 2 - Percussion (Finger Cymbals, 2-E Alto Saxophone 2 Bass Drum) 2-B Tenor Saxophone Symphony No. V: Elements is also available as follows: MP 99158, I. Sun in C $135.00 Additional Full Score, Movement I $25.00 MP 99160, III. Wind in Eb $200.00 Additional Full Score, Movement III $45.00 PrintedMP 99157, Use Symphony No. RequiresV (Complete, Mvts. I - III) $410.00 Purchase Additional Full Score, Movements I - III $85.00 Score & Parts $140.00 Additional Full Score $30.00 Musica Propria, Inc. Additional Parts @ $3.00 P. O. Box 680006 San Antonio TX 78268 All prices U.S. www.musicapropria.com Edition Number: MP 99159 email: [email protected] About the Composer Julie Ann Giroux was born 1961 in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, and raised in Phoenix, Arizona and Monroe, Louisiana. -

MUSC 2019.12.12 Honorbandprog

THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC, THEATRE, AND DANCE PRESENTS 2019 DECEMBER 12–14 COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY Are you interested in joining the largest, loudest, and most visible student organization on the CSU campus? Our students forge enduring skills and lifelong friendships through their dedication and hard work in service of Colorado State University. JOIN THE MARCHING BAND! • 240 MEMBERS REPRESENT ALL MAJORS • SCHOLARSHIPS FOR EVERY STUDENT AUDITION DEADLINE: JULY 13, 2020* *Color guard and drumline auditions (in-person) June 6, 2020 INFORMATION AND AUDITION SUBMISSION: MUSIC.COLOSTATE.EDU/BANDS/JOIN bands.colostate.edu #csumusic THURSDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 12, 2019 AT 7:30 P.M. COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SYMPHONIC BAND PRESENTS: HERstory T. ANDRÉ FEAGIN, conductor SHERIDAN MONROE LOYD, graduate student conductor Early Light (1999) / CAROLYN BREMER Albanian Dance (2005) / SHELLY HANSON Sheridan Monroe Loyd, graduate student conductor Terpsichorean Dances (2009) / JODIE BLACKSHAW One Life Beautiful (2010) / JULIE GIROUX Wind Symphony No. 1 (1996) / NANCY GALBRAITH I. Allegro II. Andante III. Vivace Jingle Them Bells (2011) / JULIE GIROUX NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Early Light (1999) CAROLYN BREMER Born: 1975, Santa Monica, California Died: 2018, Long Beach, California Duration: 6 minutes Early Light was written for the Oklahoma City Philharmonic and received its premiere in July 1995. The material is largely derived from “The Star-Spangled Banner.” One need not attribute an excess of patriotic fervor in the composer as a source for this optimistic homage to our national anthem; Carolyn Bremer, a passionate baseball fan since childhood, drew upon her feelings of happy anticipation at hearing the anthem played before ball games when writing her piece. -

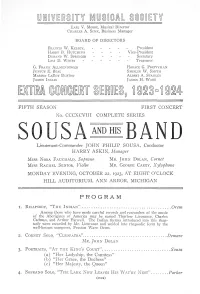

Til OOIHT Seiel 1 %

EISITY Mil 8 IB AIL SOCIETY EARL V. MOORE, Musical Director CHARLES A. SINK, Business Manager BOARD OF DIRECTORS FRANCIS W. KELSEY, President HARRY B. HUTCH INS Vice-President DURAND W. SPRINGER Secretary- LEVI D. WINES Treasurer G. FRANK ALLMENDINGER HORACE G. PRETTYMAN JUNIUS E. BEAL SHIRLEY W. SMITH MARION LEROY BURTON ALBERT A. STANLEY JAMES INGLIS JAMES H. WADE A Til OOIHT SEiEl 1 % FIFTH SEASON FIRST CONCERT No. CCCXCVIII COMPLETE SERIES SOUSA AND HIS BAND Lieutenant-Commander JOHN PHILIP SOUSA, Conductor HARRY ASKIN, Manager Miss NORA FAUCHALD, Soprano MR. JOHN DOLAN, Comet Miss RACHEL, SENIOR, Violin MR. GEORGE CAREY, Xylophone MONDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 22, 1923, AT EIGHT O'CLOCK HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM 1. RHAPSODY, "THE INDIAN" Orem Among those who have made careful records and researches of the music of the Aborigines of America may be named Thurlow Lieurance, Charles Cadman, and Arthur Farwell. The Indian themes introduced into this rhap sody were recorded by Mr. Lieurance and welded into rhapsodic form by the well-known composer, Preston Ware Orem. 2. CORNET SOLO, "CLEOPATRA" Denture MR. JOHN DOLAN 3. PORTRAITS, "AT THE KING'S COURT" Sousa (a) "Her Ladyship, the Countess" (b) "Her Grace, the Duchess" (c) "Her Majesty, the Queen" 4. SOPRANO SOLO, "THE LARK NOW LEAVES HIS WAT'RY NEST" Parker (OVER) PROGRA M—Continued 5. FANTASY, "THE VICTORY BALL" ScJielling This is Mr. Schelling's latest-completed work. The score bears the inscription, "To the memory of an American soldier." The fantasy is based on Alfred Noyes' poem, "The Victory Ball," here with reprinted, by permission, from "The Elfin Artist and Other Poems," by Alfred Noyes, copyright 1920, by Frederick A. -

JOHN PHILIP SOUSA MARCHES (Reprinted from Their Original Editions) Sunday, October 28, 2012

BOVACO Catalog ‐ JOHN PHILIP SOUSA MARCHES (reprinted from their original editions) Sunday, October 28, 2012 Catalog# Price Across The Danube March BOV‐S3689‐00 $60.00 America First March BOV‐S3690‐00 $60.00 Anchor And Star March BOV‐S3691‐00 $60.00 The Beau Ideal March BOV‐S3693‐00 $60.00 The Belle Of Chicago March BOV‐S3694‐00 $60.00 Extra condensed score BOV‐S3694‐01 $6.00 Ben Bolt March BOV‐S3695‐00 $60.00 Bonnie Annie Laurie March BOV‐S3697‐00 $60.00 The Boy Scouts Of America March BOV‐S3698‐00 $60.00 The Bride Elect March BOV‐S3699‐00 $60.00 Bullets and Bayonets March BOV‐S3700‐00 $60.00 The Chantyman's March BOV‐S3701‐00 $60.00 The Charlatan March BOV‐S3702‐00 $60.00 Comrades Of The Legion March BOV‐S3703‐00 $60.00 Congress Hall March BOV‐S3704‐00 $60.00 The Corcoran Cadets March BOV‐S3705‐00 $60.00 Extra condensed score BOV‐S3705‐01 $6.00 The Crusader March BOV‐S3706‐00 $60.00 Extra condensed score BOV‐S3706‐01 $6.00 Daughters Of Texas March BOV‐S3707‐00 $60.00 The Diplomat March BOV‐S3708‐00 $60.00 All amounts are USD. Prices are subject to change without notice. Page 1 BOVACO Catalog ‐ Sousa Marches Catalog# Price Extra condensed score BOV‐S3708‐01 $6.00 The Directorate March BOV‐S3709‐00 $60.00 El Capitan March BOV‐S3710‐00 $60.00 Esprit De Corps March BOV‐S3711‐00 $60.00 The Fairest Of The Fair March BOV‐S3712‐00 $60.00 Extra condensed score BOV‐S3712‐01 $6.00 One of Sousa’s most melodic and tuneful marches! Composed 1908. -

FREDERICK FENNELL and the EASTMAN WIND ENSEMBLE: the Transformation of American Wind Music Through Instrumentation and Repertoire

FREDERICK FENNELL AND THE EASTMAN WIND ENSEMBLE: The Transformation of American Wind Music Through Instrumentation and Repertoire Jacob Edward Caines Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Master of Arts degree in Musicology School Of Music Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Jacob Edward Caines, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 i Abstract The Eastman Wind Ensemble is known as the pioneer ensemble of modern wind music in North America and abroad. Its founder and conductor, Frederick Fennell, was instrumental in facilitating the creation and performance of a large number of new works written for the specific instrumentation of the wind ensemble. Created in 1952, the EWE developed a new one-to-a-part instrumentation that could be varied based on the wishes of the composer. This change in instrumentation allowed for many more compositional choices when composing. The instrumentation was a dramatic shift from the densely populated ensembles that were standard in North America by 1952. The information on the EWE and Fennell is available at the Eastman School of Music’s Ruth Watanabe Archive. By comparing the repertory and instrumentation of the Eastman ensembles with other contemporary ensembles, Fennell’s revolutionary ideas are shown to be unique in the wind music community. Key Words - EWE (Eastman Wind Ensemble) - ESB (Eastman Symphony Band) - Vernacular - Cultivated - Wind Band - Wind Ensemble - Frederick Fennell - Repertoire i Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been completed without the support of many people. Firstly, my advisor, Prof. Christopher Moore. Without his constant guidance, and patience, this document would have been impossible to complete. -

Adam Schoenberg

SCHEDULE OF PERFORMANCES AND EVENTS - check denison.edu/series/tutti Monday, March 4, 6:30 pm, Knapp Performance Space Artist Talk with Vail Visiting Artist Tara Booth, ‘Inward & Onward: The Contemporary Ceramics of Tara Booth,’ Tuesday March 5, 10:00 am Swasey Chapel Workshop with Third Coast Percussion, ‘Think Outside the Drum” 8:00 pm, Denison Museum The Weather Project - Artist Talk and Concert with Nathalie Miebach and Student Composers Concert with ETHEL and Students, Wednesday, March 6, 1:30 pm, Swasey Chapel Composers Workshop with Third Coast Percussion on Composition, Swasey Chapel 6:30 pm, Burke Recital Hall Composition and Improvisation: Philosophers and Musicians in Dialogue with John Carvalho, Ted Gracyk, Mark Lomax II and ETHEL Thursday, March 7, 11:30 am, Burke Rehearsal Hall Composition Seminar with Adam Schoenberg, 3:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert One with Guest Artists and the Columbus Symphony Quartet 7:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert Two with Denison Wind Ensemble and Symphony Orchestra, with guest artists ETHEL Friday, March 8, 10:00 am, Burke Recital Hall Concert Three with Faculty, Students and Guest Artists 11:30 am, Burke Rehearsal Room Conversation with: Third Coast Percussion, ETHEL, and Adam Schoenberg 3:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert Four with Chamber Singers, Jazz Ensemble, Faculty and Guest Artists 7:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert Five ‘Words and Music with ETHEL and Michael Lockwood Crouch, actor, and Denison Creative Writing Students, Saturday, March 9, 10:00 am, Knapp Performance Space Concert Six with Faculty and Guest Artists, 11:00 am, Composers Forum - Knapp (various locations) - Composers 3:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert Seven ‘New American Music Project 3. -

DIRECTOR of DEVELOPMENT KANSAS CITY SYMPHONY Kansas City, Missouri

DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT KANSAS CITY SYMPHONY Kansas City, Missouri http://kCsymphony.org The Aspen Leadership Group is proud to partner with the Kansas City Symphony in the search for a Director of Development. The Director of Development is the leader of the Symphony’s Development department and a member of the Orchestra’s senior-management team. The Director is responsible for establishing, facilitating, and evaluating a highly professional, ethical, and successful fundraising program. This person mentors and manages staff and volunteers in their design and implementation of annual, capital, endowment, and planned-giving programs. Major-gifts solicitation, stewardship, Board support, and a positive public presence are important facets of this position. The Director of Development will have a passion for symphonic music and be able to share her/his enthusiasm for the role of the symphony orchestra in a vibrant community. S/he will be able to articulate with personal conviction the mission and vision of the organization. The Director will appreciate and support the collaborative culture of the Kansas City Symphony, be comfortable sharing authority and delegate work accordingly, but will not hesitate to make decisions. The successful candidate will be a broad and disciplined thinker who identifies opportunities, prioritizes tasks in a demanding work environment, and overcomes obstacles. S/he will be proactive, solution-oriented and possess a balance of creativity and pragmatism. The Symphony places a premium on relationship-based fundraising and excellent stewardship of donors. The successful candidate will be an outstanding listener, a strategic fundraiser, and possess a warm and engaging public presence. The Director will be someone donors enjoy spending time with and will be perceived as an organizational leader. -

Easter 2021 ANOFOB Program

Welcome to the first ever Australian National Online Festival of Bands. The Band Association of NSW along with our event partners, Besson Buffet Group, Brassbanned.com, OneMusic Australia, Yamaha Music Australia and with the sup- port of CreateNSW are pleased to be hosting this inaugural event. Born out of extraordinary circumstances, I am truly humbled by the response from our Banding community across Australia to this re-styled National festival. With the cancellation of the traditional In-Venue Nationals, which were to be held in Newcastle, the BANSW Management Committee were acutely aware of the im- portance of maintaining a Banding presence over the Easter weekend. Tradition combined with the need to adapt, meant “outside the box” thinking. This resulted in significant simplification of the rules and the creation of a National Online event which would be inclusive and accessible for all Recognising the inability of many bands to have had complete rehearsals while oth- ers had few limits on rehearsals, we created a flexible Festival style event. With few registration and membership requirements bands could participate in whichever events and musical items they were able to present. A reduced minimum member number allow bands with reduced membership to still have a reason to rehearse, and attract players back to band. To this end, with 74 bands from all states and territories, including, the Arafura Wind Ensemble from the Northern Territory, appearing for their first ever National event, and the St Louis Brass Band from the USA, I believe we have absolutely achieved what we set out to. Being online has presented challenges for both Bands and organisers.