American Music Research Center Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 September 2021

9 September 2021 12:01 AM Uuno Klami (1900-1961) Serenades joyeuses Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Jussi Jalas (conductor) FIYLE 12:07 AM Johann Gottlieb Graun (c.1702-1771) Sinfonia in B flat major, GraunWV A:XII:27 Kore Orchestra, Andrea Buccarella (harpsichord) PLPR 12:17 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Violin Sonata in G minor Janine Jansen (violin), David Kuijken (piano) GBBBC 12:31 AM Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Slavonic March in B flat minor 'March Slave' BBC Philharmonic, Rumon Gamba (conductor) GBBBC 12:41 AM Maria Antonia Walpurgis (1724-1780) Sinfonia from "Talestri, Regina delle Amazzoni" - Dramma per musica Batzdorfer Hofkapelle, Tobias Schade (director) DEWDR 12:48 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Sonata for piano (K.281) in B flat major Ingo Dannhorn (piano) AUABC 01:00 AM Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805) Quintet for guitar and strings in D major, G448 Zagreb Guitar Quartet, Varazdin Chamber Orchestra HRHRT 01:19 AM Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) Symphony No.3 (Op.27) "Sinfonia espansiva" Janne Berglund (soprano), Johannes Weisse (baritone), Stavanger Symphony Orchestra, Niklas Willen (conductor) NONRK 02:01 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Estampes, L.100 Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:14 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Etude in C minor Op.10'12 'Revolutionary' Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:17 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Etude in E major, Op.10'3 Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:20 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Etude in C minor Op.25'12 Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:23 AM Constantin Silvestri (1913-1969) Chants nostalgiques, -

Sustainability Report Monster Beverage Corporation

2020 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT MONSTER BEVERAGE CORPORATION FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENT This Report contains forward-looking statements, within the meaning of the U.S. federal securities laws as amended, regarding the expectations of management with respect to our plans, objectives, outlooks, goals, strategies, future operating results and other future events including revenues and profitability. Forward-look- ing statements are generally identified through the inclusion of words such as “aim,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “drive,” “estimate,” “expect,” “goal,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “project,” “strategy,” “target,” “hope,” and “will” or similar statements or variations of such terms and other similar expressions. These forward-looking statements are based on management’s current knowledge and expectations and are subject to certain risks and uncertainties, many of which are outside of the control of the Company, that could cause actual results and events to differ materially from the statements made herein. For additional information about the risks, uncer- tainties and other factors that may affect our business, please see our most recent annual report on Form 10-K and any subsequent reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, including quarterly reports on Form 10-Q. Monster Beverage Corporation assumes no responsibility to update any forward-looking state- ments whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. 2020 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT #UNLEASHED TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE CO-CEOS 1 COMPANY AT A GLANCE 3 INTRODUCTION 5 SOCIAL 15 PRODUCT RESPONSIBILITY 37 ENVIRONMENTAL 45 GOVERNANCE 61 CREDITS AND CONTACT 67 INTRODUCTION MONSTER BEVERAGE CORPORATION LETTER FROM THE CO-CEOS As Monster publishes its first Sustainability Report, we cannot ignore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 12, 1892-1893

FORD'S GRAND OPERA HOUSE, BALTIMORE. BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA. ARTHUR NIKISCH, Conductor. Twelfth Season, 1892-93. ONLY CONCERT IN BALTIMORE THIS SEASON, Monday Evening, October 31, 1892, At Eight o'clock. With Historical and Descriptive Notes by William F. Apthorp. PUBLISHED BY C A. ELLIS, MANAGER. The Mason &. Hamlin Piano has been exhibited in three Great World's Competitive Exhibitions, and has received the HIGHEST POSSIBLE AWARD at each one, as follows : AMSTERDAM, . 1888. NEW ORLEANS, . 1888. JAMAICA, . ... 1891. Because of an improved method of construction, in- troduced in 1882 by this Company, the Mason Sc Hamlin PIANOFORTES Are more durable and stand in tune longer than any others manufactured. CAREFUL INSPECTION RESPECTFULLY INVITED. BOSTON. NEW YORK. CHICAGO. Local Representatives, OTTO SUTRO & CO., - BALTIMORE (2) Boston Fords _ i 4i// Grand Opera Symphony f| House. \Jl Of Ifc/O Li CjL Season of 1892-93. Mr. ARTHUR NIKISCH, Conductor. Monday Evening, October 31, At Eight. PROGRAMME. " Karl Goldmark ------ Overture, " Sakuntala " K. M. von Weber - Aria from " Oberon," " Ocean, thou mighty monster y Richard Wagner - Vorspiel and "Liebestod" (Prelude and " Love-death') y " from " Tristan und Isolde Franz Liszt - - - - Song with Orchestra, "Loreley" Ludwig van Beethoven - - Symphony in C minor, No. 5, Op. 67 Allegro con brio (C minor), - 2-4. Andante con moto (A-flat major), - - 3-8. | Scherzo, Allegro (C minor), - 3-4. i Trio (C major), - 3-4. Finale, Allegro (C major), - 4-4. Soloist, Miss EMMA JUCH, (3) : SHORE LINE BOSTON TA NEW YORK NEW YORK TO1 \J BOSTON Trains leave either city, week-days, except as noted DAY EXPRESS at 10.00 A.M. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

House Resolution No.110

HOUSE RESOLUTION NO.110 Rep. Reilly offered the following resolution: 1 A resolution to declare May 17-21, 2021, as Home Education 2 Week in the state of Michigan. 3 Whereas, The state of Michigan is committed to excellence in 4 education; and 5 Whereas, Michigan law affirms that it is the natural 6 fundamental right of parents and legal guardians to determine and 7 direct the care, teaching, and education of their children; and 8 Whereas, Research demonstrates conclusively that educational 9 alternatives and direct family participation improve academic 10 performance; and 11 Whereas, Families engaged in home-based education are not 12 dependent on public, tax-funded resources for their children's 13 education, thus saving Michigan taxpayers thousands of dollars Home Education W 21H 2 1 annually; and 2 Whereas, Educating children at home was the predominant form 3 of education during much of our nation’s history; and 4 Whereas, Home education has a long history of success in our 5 country, producing such notable Americans as George Washington, 6 Benjamin Franklin, Patrick Henry, John Quincy Adams, John Marshall, 7 Robert E. Lee, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Edison, Helen Keller, Clara 8 Barton, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Franklin D. Roosevelt, George Patton, 9 Douglas MacArthur, Frank Lloyd Wright, John Philip Sousa, and Tim 10 Tebow among many others; and 11 Whereas, Michigan’s home-educated students are being equipped 12 to be successful, informed, engaged, ethical, and productive 13 citizens who enrich our society and contribute to the well-being -

RODGERS, HAMMERSTEIN &Am

CONCERT NO. 1: IT'S ALL IN THE NUMBERS TUESDAY JUNE 14, 2005 ARTEL METZ DRIVE, 7:30 pm SOLOISTS: Trumpet Quartet Lancaster HS Concert Choir - Gary M. Lee, Director SECOND CENTURY MARCH A. Reed SECOND SUITE FOR BAND G. Holst FOUR OF A KIND J. Bullock Trumpet Quartet IRISH PARTY IN THIRD CLASS R. Saucedo SELECTIONS FROM A CHORUS LINE J. Cavacas IRVING BERLIN'S AMERICA J. Moss WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHIN' IN Traditional Lancaster HS Concert Choir - Gary M. Lee, Director 23 SKIDOO Whitcomb STAR SPANGLED SPECTACULAR G. Cohan GALLANT SEVENTH MARCH J. P. Sousa CONCERT NO. 2: RODGERS, HAMMERSTEIN & HART, WITH HEART TUESDAY JUNE 21, 2005 ARTEL METZ DRIVE, 7:30 pm SOLOISTS: Deborah Jasinski, Vocalist Bryan Banach, Piano Pre-Concert Guests: Lancaster H.S. Symphonic Band RICHARD RODGERS: SYMPHONIC MARCHES Williamson SALUTE TO RICHARD RODGERS T. Rickets LADY IS A TRAMP Hart/Rodgers/Wolpe Deborah Jasinski, Vocalist SHALL WE DANCE A. Miyagawa SHOWBOAT HIGHLIGHTS Hammerstein/Kerr SLAUGHTER ON 10TH AVENUE R. Saucedo Bryan Banach, Piano YOU'LL NEVER WALK ALONE arr. Foster GUADALCANAL MARCH Rodgers/Forsblad CONCERT NO. 3: SOMETHING OLD, NEW, BORROWED & BLUE TUESDAY JUNE 28, 2005 ARTEL METZ DRIVE, 7:30 pm SOLOISTS: Linda Koziol, Soloist Dan DeAngelis & Ben Pulley, Saxophones The LHS Acafellas NEW COLONIAL MARCH R. B. Hall THEMES LIKE OLD TIMES III Barker SHADES OF BLUE T. Reed Dan DeAngelis, Saxophone BLUE DEUCE M. Leckrone Dan DeAngelis & Ben Pulley, Saxophones MY OLD KENTUCKY HOME Foster/Barnes MY FAIR LADY Lerner/Lowe BLUE MOON Rodgers/Hart/Barker Linda Koziol, Soloist FINALE FROM NEW WORLD SYMPHONY Dvorak/Leidzon BOYS OF THE OLD BRIGADE Chambers CONCERT NO. -

American Spiritual Program Fall 2009

Saturday, September 26, 2009 • 7:30 p.m. Asbury United Methodist Church • 1401 Camden Avenue, Salisbury Comprised of some of the finest voices in the world, the internationally acclaimed ensemble offers stirring renditions of Negro spirituals, Broadway songs and other music influenced by the spiritual. This concert is sponsored by The Peter and Judy Jackson Music Performance Fund;SU President Janet Dudley-Eshbach; Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs Diane Allen; Dean Maarten Pereboom, Charles R. and Martha N. Fulton School of Liberal Arts; Dean Dennis Pataniczek, Samuel W. and Marilyn C. Seidel School of Education and Professional Studies; the SU Foundation, Inc.; and the Salisbury Wicomico Arts Council. THE AMERICAN SPIRITUAL ENSEMBLE EVERETT MCCORVEY , F OUNDER AND MUSIC DIRECTOR www.americanspiritualensemble.com PROGRAM THE SPIRITUAL Walk Together, Children ..........................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Jacob’s Ladder ..........................................................................................................arr. Harry Robert Wilson Angelique Clay, Soprano Soloist Plenty Good Room ..................................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Go Down, Moses ............................................................................................................arr. Harry T. Burleigh Frederick Jackson, Bass-Baritone Is There Anybody Here? ....................................................................................................arr. -

559396 Bk Sousa

AMERICAN CLASSICS John Philip SOUSA Music for Wind Band • 13 Overture to Katherine Words of Love Waltzes Mama and Papa Mother Goose March The Central Band of the RAF Keith Brion John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) occasion Sousa composed a long and grand inaugural 9 Paroles d’Amour – Waltzes (1880) march, highlighting the grand ceremony with fanfares, Loosely translated as “The words (lyrics) of love”, Works for Wind Band, Volume 13 processionals and lyrical counter themes. these tuneful waltzes were great favorites of Sousa. John Philip Sousa personified turn-of-the-century operas and operettas. His principles of instrumentation They are formulated in the popular waltz styles of America, the comparative innocence and brash energy and tonal color influenced many classical composers. 6 President Garfield’s Funeral March Johann Strauss Jr. and Emile Waldteufel. Dating from of a still new nation. His ever touring band represented His robust, patriotic operettas of the 1890s helped ‘In Memoriam’ (1881) Sousa’s first year as leader of the Marine Band they are America across the globe and brought music to introduce a truly native musical attitude in American On July 2nd, 1881, four months after his inauguration, dedicated to the commandant of the Marine Corps. hundreds of American towns. John Philip Sousa, born theater. President James Garfield was shot by an assassin as he While never published they later became a constant 6th November, 1854, reached this exalted position with boarded a train in Washington en route to deliver a staple of Sousa’s Band’s touring programs during the startling quickness. In 1880, at the age of 26, he became 1 Occidental March (1887) speech at his alma mater, Williams College. -

U.S. Marine Band Bios

WOLF TRAP HOLIDAY SING-A-LONG FROM HOME ABOUT THE ARTISTS “THE PRESIDENT’S OWN” UNITED STATES MARINE BAND Established by an Act of Congress in 1798, the United States Marine Band is America’s oldest continuously active professional musical organization. Its mission is unique—to provide music for the President of the United States and the Commandant of the Marine Corps. President John Adams invited the Marine Band to make its White House debut on New Year’s Day, 1801, in the then-unfinished Executive Mansion. In March of that year, the band performed for Thomas Jefferson’s inauguration and it is believed that it has performed for every presidential inaugural since. In Jefferson, the band found its most visionary advocate. An accomplished musician himself, Jefferson recognized the unique relationship between the band and the Chief Executive and he is credited with giving the Marine Band its title, “The President’s Own.” COLONEL JASON K. FETTIG, director Colonel Jason K. Fettig is the 28th director of “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band. He joined in 1997 as a clarinetist and assumed leadership of the Marine Band in July of 2014. He was promoted to his present rank in August 2017 by President Donald J. Trump, becoming the third director of “The President’s Own” to be promoted to colonel in a White House ceremony. As director, Col. Fettig is the music adviser to the White House and regularly conducts the Marine Band and Marine Chamber Orchestra at the Executive Mansion and at all Presidential Inaugurations. He also serves as music director of Washington, D.C.’s historic Gridiron Club, a position held by every Marine Band Director since John Philip Sousa. -

Til OOIHT Seiel 1 %

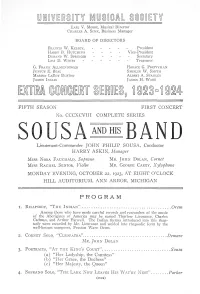

EISITY Mil 8 IB AIL SOCIETY EARL V. MOORE, Musical Director CHARLES A. SINK, Business Manager BOARD OF DIRECTORS FRANCIS W. KELSEY, President HARRY B. HUTCH INS Vice-President DURAND W. SPRINGER Secretary- LEVI D. WINES Treasurer G. FRANK ALLMENDINGER HORACE G. PRETTYMAN JUNIUS E. BEAL SHIRLEY W. SMITH MARION LEROY BURTON ALBERT A. STANLEY JAMES INGLIS JAMES H. WADE A Til OOIHT SEiEl 1 % FIFTH SEASON FIRST CONCERT No. CCCXCVIII COMPLETE SERIES SOUSA AND HIS BAND Lieutenant-Commander JOHN PHILIP SOUSA, Conductor HARRY ASKIN, Manager Miss NORA FAUCHALD, Soprano MR. JOHN DOLAN, Comet Miss RACHEL, SENIOR, Violin MR. GEORGE CAREY, Xylophone MONDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 22, 1923, AT EIGHT O'CLOCK HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM 1. RHAPSODY, "THE INDIAN" Orem Among those who have made careful records and researches of the music of the Aborigines of America may be named Thurlow Lieurance, Charles Cadman, and Arthur Farwell. The Indian themes introduced into this rhap sody were recorded by Mr. Lieurance and welded into rhapsodic form by the well-known composer, Preston Ware Orem. 2. CORNET SOLO, "CLEOPATRA" Denture MR. JOHN DOLAN 3. PORTRAITS, "AT THE KING'S COURT" Sousa (a) "Her Ladyship, the Countess" (b) "Her Grace, the Duchess" (c) "Her Majesty, the Queen" 4. SOPRANO SOLO, "THE LARK NOW LEAVES HIS WAT'RY NEST" Parker (OVER) PROGRA M—Continued 5. FANTASY, "THE VICTORY BALL" ScJielling This is Mr. Schelling's latest-completed work. The score bears the inscription, "To the memory of an American soldier." The fantasy is based on Alfred Noyes' poem, "The Victory Ball," here with reprinted, by permission, from "The Elfin Artist and Other Poems," by Alfred Noyes, copyright 1920, by Frederick A. -

Jubilee Singers Archives 1858-1924 Reprocessed by Aisha M. Johnson Special Collections Librarian Fisk University September 2013

Jubilee Singers Archives 1858-1924 Reprocessed by Aisha M. Johnson Special Collections Librarian Fisk University September 2013 Background: The tradition of excellence at Fisk has developed out of a history marked by struggle and uncertainty. The Fisk Jubilee Singers originated as a group of students who set out on a concert tour of the North on October 6, 1871 to save a financially ailing school. Their ages ranged from fifteen to twenty-five years old. The idea to form the group was conceived by George L. White, the University’s treasurer, against the disapproval of the University. White borrowed money for the tour. In the beginning, the group met with failure, singing classical and popular music. When they began to sing slave songs, they bought spirituals to the attention of the world during their national and European concerts. It was White who gave them the name Jubilee Singers in memory of the Jewish Year of Jubilee. The original Jubilee Singers (1871) are Minnie Tate, Greene Evans, Isaac Dickerson, Jennie Jackson, Maggie Porter, Ella Sheppard, Thomas Rutling, Benjamin Holmes, Eliza Walker, and George White as director. The Singers raised $150,000, which went to the building of Jubilee Hall, now a historic landmark. Today, the tradition of the Jubilee Singers continues at Fisk University. On October 6th of every year, Fisk University pauses to observe the anniversary of the singers' departure from campus in 1871. The contemporary Jubilee Singers perform during the University convocation and conclude the day's ceremonies with a pilgrimage to the grave sites of the original Jubilee Singers to sing. -

High School Band Required List

2021-2022 High School Band Required List Table of Contents Click on the links below to jump to that list Band Group I (Required) Group II (Required) Group III (Required) BAND 2021‐2022 ISSMA REQUIRED LIST HIGH SCHOOL Perform as published unless otherwise specified. OOP = Permanently Out of Print * = New Additions or Changes this year Approximate times indicated for most selections GROUP I (REQUIRED) Aegean Festival Overture Makris / Bader E.C. Schirmer 10:00 Aerial Fantasy Michael A. Mogensen Barnhouse 10:30 Al Fresco Karel Husa Associated Music 12:13 American Faces David R. Holsinger TRN 6:00 American Hymnsong Suite (mvts. 1 & 3 or mvts. 1 & 4) Dwayne Milburn Kjos 3:11 / 1:45 / 1:50 American Overture For Band Joseph Willcox Jenkins Presser 115‐40040 5:00 American Salute Gould / Lang Belwin / Alfred 4:45 And The Mountains Rising Nowhere Joseph Schwantner European American Music 12:00 And The Multitude With One Voice Spoke James Hosay Curnow 8:00 Angels In The Architecture Frank Ticheli Manhattan Beach 15:00 Apotheosis Kathryn Salfelder Kon Brio 5:45 Apotheosis Of This Earth Karel Husa Associated Music 8:38 Archangel Raphael Leaves A House Of Tobias Masanori Taruya Foster Music 9:00 Armenian Dances Part I Alfred Reed Sam Fox / Plymouth 10:30 Armenian Dances Part II Alfred Reed Barnhouse 9:30 Army Of The Nile (March) Alford or Alford / Fennell Boosey & Hawkes 3:00 Aspen Jubilee Ron Nelson Boosey & Hawkes 10:00 Asphalt Cocktail John Mackey Osti Music 6:00 Austrian Overture Thomas Doss DeHaske 10:20 Away Day A.