The New York World's Fair of 1964-1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ger.* One of the Common Beliefs of Lawyers, and Particularly of Aca- Demic Lawyers, Is That We Can Save the World Through the Processes of Law

THE POWER BROKER: ROBERT MOSES AND THE FALL OF NEW YORK. By Robert A. Caro. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974. Pp. 1246. Clothbound $17.95. Paperbound $7.95. Reviewed by Peter D. Jun- ger.* One of the common beliefs of lawyers, and particularly of aca- demic lawyers, is that we can save the world through the processes of law. This belief is a source of comfort, and perhaps of inspiration, to the profession, but there is some reason to wonder just how great an impact "law" does have in really shaping events when confronted by big questions-or big men. The story unfolded in Robert Caro's book, The Power Broker, Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, offers a case in point. Caro is not a lawyer, and therefore perhaps not a firm believer in the efficacy of law. He is a journalist, mesmerized by the rising and falling of New York and of that shadowy colossus, Robert Moses. As a result, he is able to expose, within his mosaic of a decaying city, not only the stork ornamenting the bathouse of Corona Pool "wearing an expression that made him look as if he were puz- zling over the physical differences in the creatures he had brought into the world,"' but also a paradigm of our most troubling problem, the irrational structure of our policy. Caro, the reporter, stands at the opposite pole from most legal writers and some of the political scien- tists. He supplies us, not with principles and definitions, but with a mass of facts of the sort that resist quantification. -

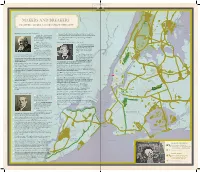

Makers and Breakers

Confidential property of University of California Press Uncorrected proofs Not for reproduction or distribution Van 12 Cortlandt Park 10 MAKERS AND BREAKERS Van Co-op Cortlandt City OLMSTED, MOSES, JACOBS SHAPE THE CITY Pelham Bay Village Park Long Island Sound frederick law olmsted (1822–1903) 14 1963–65: Presides over transformation of Flushing Meadows for BRONX o Cr ss Br onx 1 August 1840: Arrives in New its second world’s fair, which flounders in finances and attendance 11 Ex py York at 18, from Connecticut, to 15 1968: Still swims in Atlantic at age 79 near longtime Babylon, clerk for a silk importer; lodges in Long Island, home Brooklyn Heights 2 1848–55: On 125 acres jane jacobs (born Jane Butzner, 1916–2006) purchased for him by his father, 1 1934: Arrives from Scranton, builds Tosomock Farm into a PA, at age 18, intent on breaking successful nursery between stints into journalism, and with her traveling sister soon moves to the West 3 February 16, 1853: Publishes Village, their “ideal neighbor- first dispatch from the South in hood” Hudson River nascent New York Times, starting 6 5 2 7 1943: Having dropped out a series that transforms him into a staunch abolitionist, respected of Columbia’s University Exten- Riverside 4 journalist, and influential public voice Triborough Park sion, rejecting formal education, Bridge 4 Fall 1857–April 1858: Spending nights at architect Calvert Vaux’s, takes job as writer at the US collaborates -

Unions and Party Politics on Long Island Party by Exchanging Jobs, Contracts and Positions for Votes

LABOR HISTORY stronghold for the Democratic Unions and Party Politics on Long Island Party by exchanging jobs, contracts and positions for votes. by Lillian Dudkiewicz-Clayman The city Democratic machine has been long-lasting. Even today, despite the election of Republicans LaGuardia, Lindsay, Giuliani and hese are interesting times for Long Island labor unions. Many of the current union leaders and activists on Long Island Bloomberg as mayors, the Almost every day, newspapers are filled with stories about were born and raised in working class families that moved to Long Democratic Party is still dominant. Tone level of government or the other looking to balance their Island from one of New York City’s five boroughs. Most have In 2012, in most of the New York budgets by laying off workers, cutting the benefits of organized stayed true to their working class roots. As they and their families City council districts, and in most workers or negotiating givebacks. On May 21, 2012, the Republican- moved to the Island, they regularly enrolled as Republicans. Their of the city’s state assembly and dominated Nassau County legislature proposed a bill that would, in unions, with only a few exceptions, supported Republican state senate districts, the primary effect, completely undermine collective bargaining. This happened candidates. This occurred despite the fact that over the years since election for the Democratic at the end of their legislative session after it had been announced WWII, the national Republican Party was the party that took nomination is viewed by many as that the bill would be tabled. -

Robert Moses

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ııı | Number ı | Fall 2007 Essays: The Landscapes of Robert Moses 3 Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Robert Moses and the Transformation of Central Park Adrian Benepe: From Playground Tot to Parks Commissioner: My Life with Robert Moses Carol Herselle Krinsky: View from a Tower in the Park: At Home in Peter Cooper Village Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Robert Moses and Robert Caro Redux Book Reviews 18 Reuben M. Rainey: Pilgrimage to Vallombrosa: From Vermont to Italy in the Footsteps of George Perkins Marsh By John Elder Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Daybooks of Discovery: Nature Diaries in Britain 1770–1870 By Mary Ellen Bellanca Nature’s Engraver: A Life of Thomas Bewick By Jenny Uglow Calendar 23 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor his issue of tenements, he cleared slums or New York City Housing in general, and the New York Site/Lines contin- but destroyed neighbor- Authority ownership, the City Planning Commission ues the reassess- hoods. The benefit of his land they occupy is not sub- in particular. He never saw Tment of the career parks has remained essen- ject to the market forces that himself as other than a of Robert Moses tially unchallenged, although normally drive real estate pragmatic enabler of public initiated earlier this year their creation as linear development. They remain works, the man who “got with Robert Moses and the appendages to highways has islands set apart from the things done.” Private-sector Modern City: The Transforma- been criticized. rest of a city that dynamical- economic development was tion of New York, the tripar- Inevitably, the forces of ly rebuilds itself as long as not part of his purview. -

Read Book the Power Broker Robert Moses and the Fall of New York

THE POWER BROKER ROBERT MOSES AND THE FALL OF NEW YORK 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert A Caro | 9780394720241 | | | | | The Power Broker Robert Moses and the Fall of New York 1st edition PDF Book How did he build so many things, acquire so many titles, move so many people? He built hundreds of playgrounds in New York City, but only one in Harlem. Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Ina, his wife and research assistant, sold the family home on Long Island and moved the Caros to an apartment in the Bronx where she had taken a teaching job, so that her husband could continue. This volume, perhaps Caro's masterpiece, as others have described it, is I believe first among equals among the greatest in my experience. He is currently at work on a fifth and final volume about Lyndon Johnson Hidden categories: All articles with dead external links Articles with dead external links from December Articles with short description Short description is different from Wikidata All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from April Articles with unsourced statements from June This is the 4th of his 5 published works that I have read and he is still my favorite non-fiction writer. How real a prospect were these, and what did the public fight look like? I love New York City, and the more I read of this masterpiece, the more I found myself needing to walk away from the book - sometimes for weeks at a time - to deal with the subject matter. It can be a drag. -

City Policy and Urban Renewal: a Case Study of Fort Greene, Brooklyn

Middle States Geographer, 1998,31: 73-82 CITY POLICY AND URBAN RENEWAL: A CASE STUDY OF FORT GREENE, BROOKLYN Winifred Curran Department of Geography Hunter College New York, NY 10021 ABSTRACT: This paper examines the primary role played by city government in the process of decline and renewal ofan inner city neighhorhood. It is a case studv ofthe Atlantic Terminal Urhan Renewal Area (A TURA) in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn. It traces the role of city government in the decline of the neighhorhood. the declaration ofthe urban renewal site, the virtual abandonment of that site for nearly thirtv years. and the later process of gentrification. The city policy of creative destruction of the landscape resulted in a rent gap in Fort Greene that provided the opportunity for the current development. The focus is on the development of Atlantic Center, a large commercial facility in addition to a development of puhlicly subsidized townhouses for middle income homeowners, huilt as a result of a public-private partnership. The citv's policy of property-led growth, in which real estate development has become a substitute for communitv development is examined. The manner in which this project has heen developed, despite the vocal opposition of the community, indicates that Atlantic Center has heen developed to recognize a short-term profit potential rather than to achie\'e the long-term revitalization ofFort Greene. INTRODUCTION practice of urban renewal. the designation of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA) may have done more to accelerate the decline of Fort The history of the Fort Greene section of Greene than to arrest and reverse it. -

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Full Download

[PDF] The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Full Download Read E-Books online The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, Download Best Book The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, Download ebook The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, Download Online The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Book, Download PDF The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, Download The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York E-Books, Download The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Online Free, Free Download The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Best Book, PDF The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York read online, Read Best Book Online The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, Read Online The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Best Book, Read Online The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Book, Read Online The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York E-Books, Read The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Online Free, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York PDF Read Online, Download ebook The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Online, Book details ● Author : Robert A. Caro ● Pages : 1336 pages ● Publisher : Knopf 1974-07-12 ● Language : English ● ISBN-10 : 0394480767 ● ISBN-13 : 9780394480763 Book Synopsis For the sheer magnitude, depth and authority of its revelations, The Power Broker stands alone--- a huge and galvanizing biography revealing not only the virtually unknown saga of one man s incredible accumulation of power, but the hidden story of the shaping (and mis-shaping) of New York through the past half-century.Robert Caro s monumental book makes public what few outsiders have known: that Robert Moses was the single most powerful man of our time in the City and in the State of New York. -

The Cross-Bronx Expressway Steve Alpert 1.011 Final Project Spring 2003

“Heartbreak Highway” The Cross-Bronx Expressway Steve Alpert 1.011 Final Project Spring 2003 The Cross-Bronx Expressway, one of the last freeways to be completed in New York City, represents the end of an era. Socially, it marked the last time a neighborhood would be torn apart while ignoring the voices of the people living there. Politically, it marked the end of Robert Moses’ career as head of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA). No planned freeway has been built in New York City since the completion of the Cross-Bronx (the Bruckner Expressway was already under construction), and the Cross-Bronx cannot reasonably be widened or rerouted. In short, the twenty years of heavy expressway construction following World War II came to a head with one of the most notorious highways still standing. After looking at a history of freeways in New York City and the development of the concept of a freeway crossing the heavily developed Bronx borough, this paper will go into the justification for the project, analyzing risks, potential costs, and potential benefits. Then, as the project unfolds, this paper will examine the social, political, and other construction problems Moses faced while still in charge of the TBTA, analyzing the costs they introduced. After sections on the Highbridge and Bruckner Interchanges, which “cap” the freeway on the west and east ends respectively, this paper concludes with a look at the effects of the Cross-Bronx, both local and national, and the state of the freeway today. History New York, in particular the New York City area, had been a pioneer in highway construction since the advent of the automobile. -

Torrey Botanical Society

Torrey Botanical Society The Historical and Extant Vascular Flora of Pelham Bay Park, Bronx County, New York 1947- 1998 Author(s): Robert DeCandido and Eric E. Lamont Source: Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, Vol. 131, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 2004), pp. 368-386 Published by: Torrey Botanical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4126941 Accessed: 18/06/2009 03:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=tbs. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Torrey Botanical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. -

Der Umbau Von New York Unter Robert Moses Und Seine Mediale Resonanz

Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen Fachbereich 04: Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften Studiengang: Geschichte und Fachjournalistik Geschichte Bachelor-Thesis Betreuer: Herr Prof. Dr. Friedrich Lenger Der Umbau von New York unter Robert Moses und seine mediale Resonanz Verfasser: Benjamin Bathke Sommersemester 2011, 6. Fachsemester Matrikelnummer: 1080575 Adolph-Kolping-Straße 5 35392 Gießen [email protected] Justus-Liebig-University Giessen Department 04: historical and cultural sciences Study course: joint degree in history and journalism Bachelor’s thesis Supervisor: Mr. Prof. Dr. Friedrich Lenger The transformation of New York under Robert Moses and its reflection in the media Author: Benjamin Bathke Summer term 2011, 6th semester at the university Matriculation number: 1080575 Adolph-Kolping-Strasse 5 35392 Giessen [email protected] CONTENTS Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... i Abbreviations.................................................................................................................................... i Selected officials with terms of office .............................................................................................. ii 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 2. THE TRANSFORMATION OF NEW YORK UNDER ROBERT MOSES ............ 5 2.1 Life and career of Robert Moses ............................................................................. -

The Age of Infrastructure: the Triumph and Tragedy of the Progressive Civil Religion

Penn History Review Volume 23 Issue 2 Fall 2016 Article 3 December 2016 The Age of Infrastructure: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Progressive Civil Religion Joseph Kiernan University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/phr Recommended Citation Kiernan, Joseph (2016) "The Age of Infrastructure: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Progressive Civil Religion," Penn History Review: Vol. 23 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/phr/vol23/iss2/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/phr/vol23/iss2/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Te Age of Infrastructure Propoganda Poster from the Second World War Celebrating the Force and Magnitude of the Tennessee Valley Authority Ten Years After its Inception 10 Joseph Kiernan Penn History Review 10 Te Age of Infrastructure The Age of Infrastructure: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Progressive Civil Religion Joseph Kiernan “And what is faith? It is not born solely or largely by the actions of one but through the contributions of millions living in the spirit of justice, with due consideration for the burdens and rights of all others.” – Senator George W. Norris (R-NE)1 INTRODUCTION During the 1930s, simmering progressivism erupted into furious activity, initiating the Age of Infrastructure in the United States of America (U.S.). After decades of piecemeal development of roads and railways at the hands of states and private corporations, Washington, D.C. took command. Gone were the railroad cabals of Charles Crocker, James J. Hill, Mark Hopkins, Collis Huntington, Leland Stanford, and Cornelius Vanderbilt. -

Robert Moses and the Real Estate City: a Reexamination of the Legacy of New York's Master Builder

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2019 Robert Moses and the Real Estate City: A Reexamination of the Legacy of New York's Master Builder Jack Fascitelli [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Real Estate Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Fascitelli, Jack, "Robert Moses and the Real Estate City: A Reexamination of the Legacy of New York's Master Builder". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2019. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/796 ROBERT MOSES AND THE REAL ESTATE CITY: A REEXAMINATION OF THE LEGACY OF NEW YORK’S MASTER BUILDER A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Center for Urban and Global Studies Trinity College by Jack Fascitelli May 2019 Introduction Throughout the four centuries New York City has existed, there has not been a more controversial figure than Robert Moses. Beginning in the 1930s, Moses used billions in public money to completely reshape the city’s built environment, road network, and public space. Over a period of almost three decades, the city’s Park Commissioner and “master builder” bulldozed not only his opposition but also large swaths of the city’s built environment, pushing through numerous projects which would change the landscape of New York City forever. By the middle of the 1960s, Moses’s career was over, and he left office with a sullied reputation that has not recovered even today. Nonetheless, his influence on New York is still evident in the modern day in the form of his infrastructure projects, urban renewal schemes, and parks.